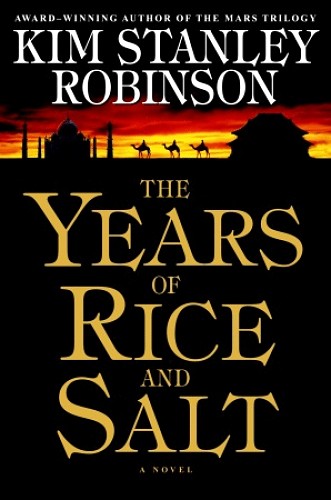

The Years of Rice and Salt is an alternate history in which all of Europe was wiped out by the Black Death. It isn’t your standard kind of alternate history. It covers the whole period from 1451 to 2002 (when it was written) using the same characters, by the method of having them die and be reincarnated multiple times in multiple places, with interludes in the Bardo, the antechamber between lives. The book isn’t really a novel, it’s a series of linked shorter pieces, some of which I love, some of which I like, and one of which I can’t stand. The characters’ names change but they retain the initial so you can tell who they are. Their personalities change with time and experience. Each of the shorter pieces has its own style, some like fairytales, some with footnotes, some very closely focused points of view and others more distanced.

The structure seems at first as if it’s going somewhere and linking the book, but it doesn’t entirely work for me, especially with the way it finishes. I’ll forgive it this because there is one bit where the characters don’t know if they are alive or dead and neither does the reader—that’s not a reading experience I get every day, and I can’t see any other way I might have had it. (Robinson’s good at doing weird things to your reading head. In Icehenge he makes you argue that the first section couldn’t have been made up.) Reincarnation is a fantasy device, but it’s treated much more science-fictionally, even with gods and demons, and there’s a hint late on that it might all be a metaphor. I don’t like that, and I felt there just isn’t enough resolution to the Bardo stuff for me to feel it’s quite justified. On the other hand, I don’t see any other way he could have written about such a vast span of time and space—a more typical dynasty or even sets of dynasties couldn’t possibly have had the range.

Kim Stanley Robinson’s always a hit-and-miss writer for me—I love some of his work and get bored by other things. If you want a calibration, I loved The Wild Shore and Pacific Edge and yawned my way through The Gold Coast. The Years of Rice and Salt does both at once—I love the first two thirds and am wearied by the end. It’s probably the book of his I’ve re-read most frequently, because I keep trying to decide what I think of it. I like the earlier part of it so much more than the later part of it, and that makes it hard to be fair to it when I’ve just finished it. Whenever I start re-reading it I love it, and whenever I finish it I’m ambivalent again.

The most interesting thing The Years of Rice and Salt does is give us an Earth without Europeans, with practically no white people and with no white point of view characters. I don’t think this is something that could have been written much earlier than it was written. SF is still so US-centric that a world with no US at all and with the cultural focus on Islam and China is really startlingly unusual. This was the first book I came across of the recent trend looking at the future of the rest of the planet (Air, River of Gods etc.) and when I first read it I was so uncritically delighted that it existed that I was prepared to overlook anything. I didn’t think about how it’s very convenient that they’re mostly women only in good times for women, the way they never happen to be in Africa or South America or Polynesia and only once (for each character) North Americans. (Kyo does start off African, but he’s taken to China in the Zheng Ho fleet as a boy.)

I think the Chinese and Islamic and Indian cultures are treated respectfully. I haven’t done close-up research into any of them myself, but they don’t contradict anything I do know, and where they are extrapolated it seems solidly done. They certainly feel very real. The book is at its best in the sections where it’s talking about daily life (“rice and salt”) and the way people live and die and are reborn and try to understand the world they find themselves in and make it a better one. I like the alchemists of Samarquand and I like the journeys, but my favourite section is about the widow Kang who has trouble climbing a ladder with her bound feet and who manages to recognise the scholar Ibrahim from previous incarnations. It’s all about life and love and respect and research. Robinson’s also very good on the way the world fits together, the way it is a planet. Someone suggested it on the Great World Novel thread, and part of why I was re-reading it now was to see whether I think it qualifies. I think it does.

Some people who know a lot more about the history of technology and early globalisation have argued with Robinson’s research in this area. I do think there’s too much similarity between his world and the real world—I don’t see why they’d have had a Renaissance analogue or a World War, and I’m not sure the Manchu invasion of China and the White Lotus Rebellion would have happened as scheduled either. I also don’t see why they’d have the same ecological problems we have, when they don’t have a widespread automobile economy and planes are only military with people and freight going in airships—their industrial revolution is sufficiently different that while they’d definitely have some pollution, I don’t think it would look as much like ours as it does. And I’m not convinced people would stay interested in Aristotle.

The whole later section, from the War of the Asuras, seems too closely modeled on us and not sufficiently an outgrowth of the world we’ve seen developing. It also becomes tediously focused on philosophy and considerations of the alternateness of the world. I’d certainly enjoy it much better if it ended before that. I can’t decide if the problems I have with the end are problems with the structure of the book or just that I can’t appreciate what he’s trying to do. I do like that by their 2002 they are as technologically advanced as we are, though they came to it by different paths.

The frame of reincarnation lets Robinson vary the lengths of the segments, and also how much of people’s lives he tells. Sometimes he starts in childhood and goes on until old age, other times it’s a very short time. “Warp and Weft,” the story of a samurai coming to the Hodenosaunee people admiring their political organisation and suggesting immunisation and some useful technological improvements, all takes place in two days. (“What these people need is a… samurai?”) The different style and length of the segments, along with the game of “spot the recurring characters in different forms,” makes it really feel like a cycle of time. I don’t know anything else that does this or even tries to do anything like this. The overall message seems to be “tend your garden and try to make the world better for future generations,” and if I’ve seen more interesting ones, I’ve also seen worse ones.

If you’re looking for science fiction with non-white characters, or fantasy with non-European mythology, or something with a huge span of time that’s aware Earth is a planet, or just something very different from anything else you’re likely to read, then do give this a try.

This was one of a few hundred books donated to my battalion when we were in Iraq. Suffice it to say, it came back to the states in my duffle bag. It’s certainly an outside read and was quite enjoyable.

“What these people need is a… samurai?”

Snrk.

I do have to read this one of these days. I found _Red Mars_ non-engaging enough that it put me off his books, but I should at least try.

Kate: Red Mars didn’t engage me either. He writes in very different styles in different books, or in this case, in the same book.

“It also become too tediously focused on philosophy and considerations of the alternateness of the world”

This was exactly my problem with it, and in fact with all Robinson books: He has a habit of turning the last few dozen pages into a soapbox, and just like every other author who does this (Heinlein, in particular, while good, succumbs to this always) it is immensely boring.

I think the focus on the Muslim world and China is somewhat fair–after all, those societies happened to be the most advanced in the world, especially at the beginning. Still, more characters and situations in other regions of the world would have been very interesting, particularly later on as they gained more importance in the book world but were actually neglected more in the narrative.

“the story of a samurai coming to the Hodenosaunee people admiring their political organisation and suggesting immunisation and some useful technological improvements,”

The Hodenosaunee League parts of the book really felt forced to me. It seemed like he was desperate to come up with some way the American continents could come into contact with the African-Asian-European landmass without the Americans getting wiped out by disease, but sadly I don’t think that’s really possible once urbanization happens in a big way in China. There’s just too many new diseases that they’d be unprepared for. Pushing back the date of contact would make that problem worse, not better.

“I’m not sure the Manchu invasion of China and the White Lotus Rebellion would have happened as scheduled either.”

Whether the Manchus or another group of horse nomads, someone would have invaded China. Horse nomads from the Eurasian steppe invading agricultural nations and then becoming assimilated was an on-going cycle for hundreds if not thousands of years. Similarly, there were dozens of rebellions of differing sizes and levels of success against the Qing–the Han have had a strong sense of ethnic identity for a long time, and any occupying power would have faced rebellions. As for it all happening on schedule–well, changing the date by a few decades wouldn’t have made a huge difference, would it?

hmmmm.

Robinson is working from a semi-deterministic model of history; he’s heavily influenced (he has said) by Marxism. So the major events of his history more-or-less occur in the same order that they do in our history. What strikes me as forced is that, somehow, democracy emerges without the influence of northern Europe. I know the Hodenosaunee were a big influence on the USA and Western Europe, but it’s hard for me to believe in Robinson’s League, anyway–I think it would have been very different.

The reincarnation novel is not entirely unique in SF (think of R.A.MacAvoy, and Jack London), but Robinson hints that it’s an actual South and East Asian form. I’m sure–I haven’t read the book in a while, so don’t ask me for cites–he’s borrowing from Asian literary forms I half-recognize, but can’t name. The Western European analog of the reincarnation novel is, in fact, the generational novel, but I find the actual reincarnation novel less forced. It seems to me more plausible that figures recur when they are, in some sense, the same figure, than when they are descendents. But I don’t think I believe in a jati that is always so much in the lead, always there at the pivotal moments. I think there would have to be a lot more lives hewing wood and drawing water. (And, after enlightenment,…)

Sure. And let’s not forget the history of ideas.

This is a complicated and deeply flawed book. It’s enormously ambitious, and I respect that. But by trying to be a close mirror to our own times, I think it fails at demonstrating the historical process as Robinson understands it. (I don’t think he’s a doctrinaire historical determinist, although I do know he’s been tremendously influenced by Marxist readings of history. It would be interesting to compare science fiction writers’ uses of grand theories of history — Heinlein of Wells, Anderson of Toynbee, Blish of Spengler, et cetera, and maybe compare them to professional futurists like Herman Kahn — but who would read it?)

Robinson is a good enough — and knowing enough — writer that the burden of proof about literary effects usually falls on the reader. Unlike Pee-Wee Herman, one can plausibly claim Robinson “meant to do that” for reasons beyond the reader’s immediate knowledge. So I’m going to concentrate on the frame rather than the filling. (Though I could go on about the filling.)

The “Bardo stuff”, of course Robinson is an ardent Tibetophile. But Tibetan Buddhism is a numerically small practice even among Asian Buddhists. It seems… partial to imply a Tibetan Buddhist metaphysics is the counterweight in a world without Europe.

Given that premise, however, I think one can draw an implication that I’m not sure Robinson intended. Europe’s population is destroyed by plague. They’re presumably reincarnated. Slightly afterward, much of Asia goes through a scientific and industrial revolution. I really doubt Robinson was trying to say, “what these people need are honky souls,” but I don’t think he thought through the effects of his combined premises.

The third problem is related, and comes from Robinson trying to make his world mirror our own too closely. Knowledge is generated by people. The principal reason for the world’s vast increase in knowledge in the past hundred years has been the vast increase in participation in that cultural activity. In a world where twenty-five percent of the population is killed, and the world takes a long time to recover, the growth of knowledge will necessarily slow down. Given this, it’s likely that Robinson’s 2002 would be less scientifically advanced than our own 2002.

One could claim that events unseen within the narrative of the novel caused the growth of knowledge to increase more quickly than it did historically — I can think of some plausible saves — but here you hit the problem of Robinson too closely paralleling our own history. He hasn’t shown why this would happen. Instead, he assumes it.

randwolf @@@@@ 6: “What strikes me as forced is that, somehow, democracy emerges without the influence of northern Europe.

What? Please explain how northern Europe was necessary to the development of democracy. Democracy–like monarchy, oligarchy, theocracy, etc.–is a form of government that has cropped up countless times across the globe, both before and after 1400. Democracy is not a unique characteristic of northern Europeans.

Heresiarch, democracy, yes. But the democracy that develops in the Hodenosaunee League is very much like US democracy. Even if we grant as much Hodenosaunee influence as, say, Jack Weatherford argues for, there’s also the influence of the European Enlightenment (and Greece & Rome) and Anglo-Saxon culture in our history. In Robinson’s history, both of these would be absent.

CarlosSkullsplitter, my impression is that Tibetan Buddhism in East Asia is analogous to Catholicism in Western Europe. The path to China leads through Tibet. To continue the analogy, even though much of Western Europe is now Protestant, Catholicism had enormous influence there. So I’ll grant Robinson that, at least.

Robinson actually begins the discussion of the literary influence of historical theories in the last part of Rice and Salt, no? It seems to me it might make an interesting PhD thesis, something that would be read by historical and literary scholars. You could add Leguin’s use of her father’s speculation on the topic as well to your list as well.

Um. Tibet is not intermediate to the spread of Buddhism in Asia. Buddhism spread to China around Tibet (which, as best as can be determined, at that time still practiced its traditional Bon religions), over the Silk Road via central Asian cultures, some of which were closely related to Persian cultures of the time, and most of which are gone in anything resembling their past forms. The scriptural connections were directly with India; the translation projects were the largest in history, until the ones associated with translating the Bible into local vernaculars. Buddhism didn’t reach Tibet on a large scale until several centuries after it reached China, and then it was based on the more “esoteric” forms then practiced in India. I’m greatly simplifying, of course, but that’s the gist.

I’m afraid the Chinese viewed the Tibetans as dangerous hillbillies for most of their history. (With some reason, since they were rather dangerous at various points.) The veneration of some — and not all — Tibetan Buddhist religious leaders came much later, through the Mongol empire. Again, greatly simplifying.

(Incidentally, I think this answers Heresiarch’s question if “a few decades” matter in passing. Of course they do.)

The third problem is related, and comes from Robinson trying to make his world mirror our own too closely. Knowledge is generated by people. The principal reason for the world’s vast increase in knowledge in the past hundred years has been the vast increase in participation in that cultural activity. In a world where twenty-five percent of the population is killed, and the world takes a long time to recover, the growth of knowledge will necessarily slow down. Given this, it’s likely that Robinson’s 2002 would be less scientifically advanced than our own 2002.

I can certainly see why Robinson wouldn’t want to write a book whose point could be interpreted as “without Europe, the world would have been centuries behind in intellectual development.”

He hits two other problems instead: “Europe was dragging the rest of the world down!” or “Europe was a null influence on the course of human development!”

The close parallelism makes it deeply flawed. He used the rime riche when he should have stuck with the slant.

Carlos, you are right, I was wrong. Teach me to rely on half-remembered tertiary sources!

Carlos, have you ever tried stepping out of an established intellectual tradition in a creative art? It is bloody difficult–sometimes there literally are no words. It may be best to regard The Years of Rice and Salt as a flawed first step, and contemplate its virtues, rather than complain it did not do enough. It would take a worldbuilding effort larger than Tolkien’s, I think, to get to the place you’d like to go in a single book. So I suppose, if enough people want to get there, it will be multiple books, possibly multiple arts.

randwolf @@@@@ 9: Ah–that makes more sense. It’s been years since I read TYORAS, so I can’t remember very many details of the Hodenosaunee democracy, but there Robinson may have been nodding towards the theory that the United States’ form of democracy was greatly influenced by ideas and structures borrowed from the Hodenosaunee League by the Puritan colonies: the use of townhall meetings, etc.

CarlosSkullsplitter @@@@@ 10: “(Incidentally, I think this answers Heresiarch’s question if “a few decades” matter in passing. Of course they do.)”

“A few decades don’t matter” isn’t exactly what I was aiming for. Let me try again.

History is a mix of determinancy and chance. One one hand, no one could have predicted Ghengis Khan’s rise, and the domination of Eurasia by a single tribe from Korea to Hungary. On the other hand, nearly all of those places had already been conquered by some tribe of horse nomads or another, in some cases multiple times. Any particular invasion may be hard to predict, but their cumulative effect over long stretches of time was.

Now, very little that happened in Europe between the 15th and 17th centuries had much of an effect on China or the Manchus. So even if Europe died off entirely, why wouldn’t roughly the same events take place at approximately the same time?

CarlosSkullsplitter @@@@@ 7: “In a world where twenty-five percent of the population is killed, and the world takes a long time to recover, the growth of knowledge will necessarily slow down.”

I was just doing some digging, and came across this: “It may have reduced the world’s population from an estimated 450 million to between 350 and 375 million in 1400.” Which means that the historical Black Plague reduced the world population by about 20% anyway. Adding the rest of the European population wasn’t, in the global view, that huge of a blow: at that point there wasn’t any scientific, mathematic, or philosophical knowledge that the Europeans had that would have been lost to the rest of the world.

Secondly, the reproductive rate of human beings is such that the main constraint on population growth is food supply. As soon as Europe was resettled, the world population would rapidly return to a similar number.

It would be interesting to compare science fiction writers’ uses of grand theories of history — Heinlein of Wells, Anderson of Toynbee, Blish of Spengler, et cetera, and maybe compare them to professional futurists like Herman Kahn — but who would read it?[i]

I would.[/i]

Heresiarch @16 writes: Adding the rest of the European population wasn’t, in the global view, that huge of a blow: at that point there wasn’t any scientific, mathematic, or philosophical knowledge that the Europeans had that would have been lost to the rest of the world.

Mmmm. This could be entering a nasty minefield but: The hole left in human advancement by an Empty America is fairly well hashed out. You don’t think a Recently Emptied Europe would have affected tech advancement?

Heresiarch @15, Looking at China in 1644, the year given as the start of the Qing — Manchu — dynasty (although the Qing war against the Ming continued for decades):

First, trade. China operated on a silver economy, and it was the largest producer of consumer goods in the world. This made it, in effect, an enormous silver magnet. The silver the Spanish extracted from the New World ended up in China, traded for Chinese manufactures like silks and porcelain. This was the dominant global macroeconomic fact for most of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. (In fact, one school of thought believes the Ming collapse was precipitated by an economic downturn caused by a decline of Spanish silver imports in the previous decade.)

Second, foodstuffs. Southern China was undergoing a massive population boom by the mid-17th century due to New World foods brought via Iberian trade: maize, sweet potatoes, peanuts, chile peppers.

Third, actual contact. The *Dutch* had colonized Taiwan by 1644. The Russians had conquered the realms north of Mongolia and the Manchu state, and Dezhnev would reach the Pacific only four years later. Meanwhile, the Jesuits were conducting an extensive scientific and religious mission at the Ming court.

Forgive me if I sound a little brusque, but this is taught in AP World History to high school students. Basic stuff. In light of that, I think I’m going to bow out of your discussion.

CarlosSkullSplitter @@@@@ 19: “The silver the Spanish extracted from the New World ended up in China, traded for Chinese manufactures like silks and porcelain.”

Right. And in TYORAS, the Chinese were raiding the New World from across the Pacific.

“Southern China was undergoing a massive population boom by the mid-17th century due to New World foods brought via Iberian trade: maize, sweet potatoes, peanuts, chile peppers.”

See above. It’s true that the silver trade and the new American crops had important effects on 17th century China that I summarily glossed over, but do you really think that a poorer, less-populous China would have been harder to conquer for the Manchus? The catalyzing event for the conquest of China was the unification of the Jurchen tribes under one banner, not the relative power of China.

“The *Dutch* had colonized Taiwan by 1644.”

Taiwan, at the point the Dutch colonized it, wasn’t Chinese–it was inhabited by a Polynesian diaspora culture. The Portuguese settlement at Macau not only both predated and outlasted the Dutch on Taiwan, but was, you know, actually in China. Neither was the Jesuit influence in the Ming court particularly strong–it was the Qing emperors who began taking advantage of Jesuit knowledge.

(Honestly, I’m surprised to find this point at the end of your list: weakest-to-strongest argument is an essay technique taught in high school English.)

Heseriarch and Carlos — could you have the conversation without the sniping?

Registering a rare disagreement with Jo Walton: The Gold Coast is one of my favorite SF novels of the last twenty years. It’s about what happened to my home planet, the rinkydink make-do authenticity of the previous American Southwest overwhelmed by insane economic bubbles. Real estate, tech, “defense” money, it doesn’t matter; it’s all lies swamping truth. I think The Gold Coast will be read a hundred years from now, as future humans try to make sense of the economic collapses and dislocations of the early 21st century.

And I’m not convinced people would stay interested in Aristotle.

Who is presented as interested in Aristotle? If the Chinese, I’d agree it’s surprising. If the Muslims, not so much; Aristotle was popular in Islamic countries at a time when he was not very popular in northern Europe.

Another Andrew: It’s the Muslims. But are they interested in him now? Because it’s the equivalent of now, and he’s still central… I’m just not convinced.

Jo:

Interesting to read your review (and reactions) and compare them to my own:

http://www.infinityplus.co.uk/nonfiction/riceandsalt2.htm

“I recommend The Years of Rice and Salt to your attention, with the caveat that it has the usual KSR strengths and weaknesses, and so will alternately thrill and annoy you. At least some of the annoyances will make you think. This is a very good piece of work by an author who knows where he’s headed, and just how to get there…”

and Keith Brooke’s

http://www.infinityplus.co.uk/nonfiction/riceandsalt.htm

(Gee, I sure miss Infinity-plus)

Also, I note I+ still has KSR’s examplary short,

“A History of the Twentieth Century, with Illustrations”:

http://www.infinityplus.co.uk/stories/history.htm

Happy reading–

Pete Tillman

It’s the Muslims. But are they interested in him (Aristotle) now?

I find this hard to say. My sense is that there has been less discontinuity in Islamic philosophy than in western philosophy, so he will still be an influence. But if anyone knows more I would be interested to hear.

In any case, I think it’s by no means impossible that he would have stayed more popular if the Europeans had not been there to re-appropriate him

I don’t have anything to add in regards to the review but I would just like to commend everyone who has commented for a very interesting discussion with relatively minimal sniping. You all strike me as learned and I will definitely be using what is said here as a basis to expand my knowledge of history as it currently appears I am woefully ignorant. Thank you all for this.

So, as a Native American, (Mi’kmaq), the idea that the Hodenosaunee needed a Japanese person to help them reach technological and political advancement really pisses me off.

Why couldn’t we have reverse engineered firearms ourselves, based off ones taken from others who landed on our continent? Why are we not capable of the social intelligence ourselves to reach political enlightenment? It stinks of white saviorism, expect instead of coming in a reimagining of European history, this time it comes in the form of a samurai.

I was really hoping for a more positive depiction of native Americans, and a free North America, but instead we’re still savages, in need of some more “advanced” society (or, in this case, person) to “save” us, and good only for being conquered. It also bothers me how quickly we just accept this foreigner in to our government.

I can’t help feeling that books with the premise “I wonder what it would be like if you wiped out this entire ethnic group” probably shouldn’t be written too often.

Interesting how mass death in Europe is the only way the author could manage an Asian biased future.