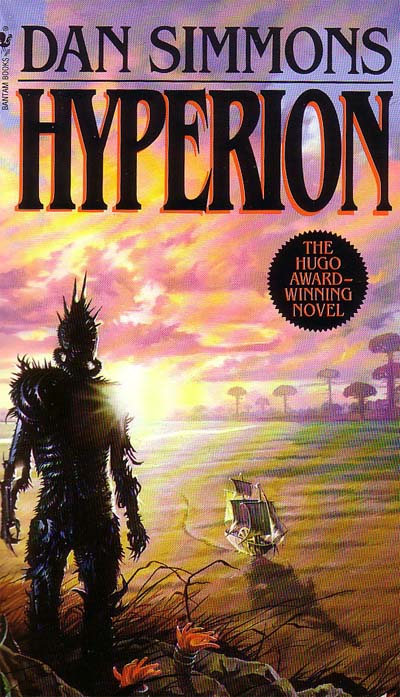

The brilliant thing about Hyperion is that it’s like the Canterbury Tales; it’s a group of people going on a pilgrimage and telling stories, only they’re telling their own stories, and they’re all about why they’re going to the planet Hyperion. But actually, the really brilliant thing is the way that the stories are all in different styles and different modes of SF. They echo earlier science fiction, they draw on it and draw it in, they allude and assume the reader will get it. And, most brilliantly of all, the universe is revealed through the stories, through mentions and details and throwaway comments in a way that’s just incomparable, so that you build up a picture of things before you hear about them, you’ve heard them mentioned without having them explained so you want the explanation when you get it. This is a masterpiece of incluing. They are pilgrims from different worlds, moving through the same universe, going to the same place of pilgrimmage. What happens when they get there doesn’t matter, Hyperion is all about the journey. There are some sequels that try to explain everything and knit it up neatly, but I generally try to pretend I haven’t read them. Hyperion is a stunning tour-de-force of characters and world and playing science fiction like an organ, and it’s good enough as it is. I love it alone and without further explanation.

When a book is a set of short stories making a novel, we call it a fix-up, and it usually shows painful seams and is at best something the book has to be forgiven. Hyperion isn’t that, although the stories are set off as stories with their own titles like “The Priest’s Tale” and subtitles like “The Man Who Cried God.” At least one of them, “Remembering Siri,” was published separately and stood perfectly well alone. But in Hyperion, although it’s all about the journey, the stories are more than the sum of their parts. It’s not that they reflect each other, it’s that they are facets that reflect things about the planet Hyperion.

The World Web is a net of worlds linked by fatline and far-caster—doors you can step through from planet to planet, so that rich have houses with rooms on different planets, you can have the bedroom in low gravity and the exercise room in high gravity. There are worlds outside the web, which you have to go to by spaceship, incurring relativistic “time debt.” It’s a future that has aged well—there are implants and a datasphere and thought processors that work something like word processors and longevity treatments and AIs that have revolted and now work for humanity, not as their slaves. There are odd little retro corners and oh yes, Earth was destroyed by a mini black hole, the “Big Mistake” several hundred years ago.

There’s a structure on Hyperion they call the Time Tombs that are travelling in the wrong direction in time, with time tides ebbing and flowing around them. And there’s a thing, a monster, called the Shrike, who is all blades, associated with them. And since before Hyperion was colonised strange things have been happening, and that’s where the pilgrims are going, some returning, and others for the first time, but all of them because their lives have become bound up with what lies there.

We have the story of the pilgrimage, and within that the six stories of the pilgrims. “The Priest’s Tale” is religious science fiction in the mode of A Case for Conscience. “The Soldier’s Tale” is romantic military SF, kind of like the Dorsai books. “The Poet’s Tale” is a spectacular extravaganza which gives a lot of explanation of the world details that have just been thrown in up to that point. It’s Zelaznian more than anything. “The Scholar’s Tale” is a heartbreaking quest of a man trying to save his daughter who is aging backwards, the best thing in the book, and it could have been written by Le Guin. “The Detective’s Tale” is cyberpunk noir, almost like Blade Runner. And the Consul’s tale, “Remebering Siri,” is like Poul Anderson. And yet all of it transcends pastiche, and all of it fits together like a puzzle-egg.

It was a shining city on a hill. Seeing the ruins today can tell you nothing of the place. The desert had advanced in three centuries; the aqueducts from the mountains have fallen and shattered; the city itself is only bones. But in its day the City of Poets was fair indeed, a bit of Socrates’s Athens with the intellectual excitement of Renaissance Venice, the artistic fervor of Paris in the days of the Impressionists, the true democracy of the first decade of Orbit City, and the unlimited future of Tau Ceti Central.

But in the end it was none of these things, of course. It was only Hrothgar’s claustrophobic meadhall with the monster waiting in the darkness without.

Hyperion expects you to be able to fit everything together, to get science fictional references, to put future histories together on the fly, and also to know what Hrothgar’s meadhall was. I think it would be a terrible book for someone new to SF, it expects you to be able to do all the tricks of reading a text as SF, but it also expects wider referents than just SF. As you can tell, it’s beautifully written. It’s deeply absorbing, one of those books you don’t want to put down.

At the end the central mysteries are not explained, except as they have been illuminated by the stories. Don’t expect closure. But trust me, it’s better that way. The reading order for the Hyperion series is “Read Hyperion and then stop.” But Hyperion itself is well worth reading and re-reading. It’s undoubtedly a masterpiece.

Yes. This is a great book, full stop. I was amazed and mesmerized when I first read it…then I started reading the sequels.

I found the second book not too bad…at least we got to see more of the lives of the characters from the first book, and a bit more of the engimatic Shrike; but the final books? Urgh. I must admit that I only got through book three and then decided there was no point to reading book four. The story just did not seem to warrant it, and the only reason to read to the end, the possible resolution of all the mysteries brought up to that point, did not, by all accounts, ever happen.

I am still amazed by _Hyperion_ (in a good way) and Dan Simmons (in a bad way). I keep trying to read other books by him and find them to be pretty execrable. How did this guy write this book?!

Got to disagree with you Ms. Walton. The reading order for the Hyperion series is “Read Hyperion and Fall of Hyperion and then stop”. {i]Hyperion is an incomplete text. Reading only it and not Fall of Hyperion is like reading Beowulf up to the point where Beowulf tears off Grendel’s arm and stopping there.

@dulac3

Simmons is one of the best authors around. What other books did you try? While Song of Kali isn’t great, Carrion Comfort and The Terror are masterpieces of horror. I will admit, though, Illium and Olympos were not as great as The Hyperion Cantos, but they are still much, much better than a lot of science fiction I have read lately.

I read _Ilium_ and really hated it. Then I tried _The Terror_ which really didn’t click for me at all. I also started _Children of the Night_ which seemed like it might be ok, but came off as a fair-to-middling horror/thriller.

Basically even the stuff that wasn’t actively bad seemed like pretty mediocre fare to me, esp. when compared to _Hyperion_.

Goblin Reservation: In this case, I don’t want the completion that’s on offer. Sometimes I’d rather have the enigmas than the proposed solution to them.

Hmm, I agree with GoblinRevolution. Dan Simmons may not be the best SF writer, or the best horror writer, or the best detective story writer, or the best historical fiction writer, but the fact that he is a damned good writer in all of these genres continues to amaze me.

I’ve read all of the Hyperion books and the fact that the third and fourth aren’t very good and the second isn’t as good as the fourth doesn’t diminish, to me, the fact that Hyperion is one of the best SF books ever written for all of the reasons Jo mentioned.

I just finished Drood. Great book.

Strange coincidence. I made a resolution to read all the Hugo and Nebula novel winners from 1990 to 2008, and I just finished Hyperion and then just had to read The Fall of Hyperion. Since then I’ve been hunting around the Internet looking for discussions of the books — there is a lot to take in — so thanks for revisiting this title. I’m not as knowledgeable about science fiction as you are, so I didn’t pick up on many of of the subtler allusions, but that didn’t prevent me from enjoying the book. Honestly, what I found more problematic was the author’s liberal use of Keats. Never having studied Romantic poetry, I found it disorienting and frustrating, and since Simmons relies more heavily on Keats in Fall, I think that’s part of why the sequel didn’t work as well for me.

I read Hyperion and Fall of Hyperion but didn’t realize the other books were related to them, I thought Simmons had two duologies. Huh. (I thought the books were well enough done, but–if I’m remembering the right books–the thing about the crosses freaked me out. I’m not likely to re-read them.)

Read the two Hyperion books and forever treat them as a finished tale. Read the Endymion stories as if they were some other story. Yes they reference a few of the Hyperion details and use many of the same stage sets (set far in the future) but they are best considered as their own entity.

I love Illium and Olympos, but I’ll admit they are tough to love. There is so much happening that it’s hard for a reader to connect the pieces. Just remember that Simmons loves the idea of there being three significant sides in any great struggle (just like in Hyperion’s AI conflict), and these books are mostly about two of them.

I consider Summer of Night a nearly perfect horror story. Go on to A Winter Haunting if you are patient enough for subtle, disturbing horror (there’s no battle royale there, just beautifully sustained creepiness). The Terror is A Winter Haunting on steroids, but it’s still a mood piece. Be prepared for that.

Then read Hard Case and be amazed at how one author can be solid in so many different genres.

dulac3: Children of the Night is a strange duck. I think of it as an experiment to see if you can take a horror story out of the realm of the supernatural without replacing magic with technobabble. It’s not entirely successful. The only defense I can offer is that when Simmons writes horror, he rarely writes about monsters, he writes about how the characters are affected by monsters – and the monster he’s most interested in is quite often the character’s own past. That doesn’t make for fast, light reading.

@@@@@ blueJo

Fair enough, but I would have hated Hyperion as much as I love it had there not been a sequel to finish the story. I mean, everything is just getting going when Hyperion[i] ends.[/i]

I love all four of the books in the Hyperion universe. The first has the most literary dazzle, so if that impresses you, it will be your favorite. The second settles down into a more prosiac space opera format, and its complex plotting is handled expertly. It goes overboard on the mystical godlike computerthing goo-goo, but all in all a satisfying and fitting conclusion.

And the Endymion and Fall of Endymion books — well, I guess I must part company with the other commenters. I think this pair of books is perfect space opera. By this point Simmons had experimented and tinkered with his formula, and with the Endymion books he locks in with a perfectly tuned, sleek racing vehicle. This is the very essence of rousing space adventure, with heroes, saints and villains, epic scope, grand scenery, exotic locales and species, the fate of the universe, etc. etc. What’s not to love? I find Aenea’s spirituality no less thoughtful or convincing than Father Dure’s self-flagellation, and in fact the latter is more creepy, exploiting shock value to manipulate the reader’s sympathies.

I’m not a big fan of ambiguous endings, but I could have been satisfied with Hyperion ending where it did. It was definitely a “the journey is the reward” type book.

I loved everyone’s stories more than I really cared about what happened when the met the shrike.

That being said, I did appreciate most of the wrap-ups of the story, but not nearly as much as the first book.

The Scholar’s Tale is my favorite part of the book. One of the most emotional pieces of SF I’ve ever read. Was anyone else reminded of it watching Benjamin Button?

Goblin Reservation: I read a review of Hyperion (I think in Asimov’s) which went on and on about how brilliant it was but was absolutely incoherently sputteringly furious about the lack of closure — they’d read it without any indication that a sequel was planned.

Nevertheless, the more books in the series I have read, the happier I am with leaving it at the end of Hyperion.

I’m trying not to remember Endymion at all, as I have a severse case of “NO! I loved this universe! You can’t do that to this universe”, and I gather Fall is worse.

bluejo:

If I recall correctly, the two books were written together but for obvious reasons published separately. I was lucky enough (for my view anyway) to have read them first as an omnibus edition.

Endymion and Fall… are a separate story which do give an interesting continuation of the universe, a ‘what happens next’ story if you will. They are not required reading to get the whole picture. While I did enjoy that continuation, I don’t think they are as good as The Hyperion Cantos and not at all necessary. I would love to pick Simmons brain about his process of thinking when he was writing them.

On a different note: I happened to grow up in the far north of Canada so I am very familiar with the landscape he uses in The Terror. If Simmons has never been to the high arctic, my wonder at his skill is even greater.

If I hadn’t read Hyperion, I would think the other three books were great. As it is, they are a tiny bit of a let down after Hyperion itself. (Also they wouldn’t make much sense without it.)

While the sequels are very different books, I think they’re still pretty darn good on their own. Lots of big epic scenes, presented very well.

As another contrasting opinion I really loved Ilium, which was my introduction to Dan Simmons’ work, I thought Olympos was just okay, and I found Hyperion not very interesting. Never read any others.

Thinking back, this probably had something to do with my finding the Trojan War mythology exceptionally cool, and certain classic literature exceptionally uncool. Some of it was my English major roommate who spent most of the year ranting about how much he hated the Canterbury Tales. So most of the clever references were lost on me. I should probably give it another shot though, and perhaps check out the sequel.

Funny coincidence:

Earlier today somebody encouraged me to check out info on Metal Gear Solid 5 for the PS3. Some clicks later I found myself reading about Revolver Ocelot (a character in the series), whose other alias is Shalashaska. This is a “mistransliteration” (Wikipedia’s word) of Sharashka, which was the informal name for secret laboratories in Soviet labor camps. The slang term for people sent to these camps? Zeks, which is what Dan Simmons called the Little Green Men on Mars in Ilium.

Twice today I came across a word I’d never heard before, from completely different starting points.

I have to agree with those who said that the reading order is Hyperion and Fall of Hyperion and stop. FoH is necessary to close on all of the plot threads that are started in H–without it, H is just six different half-stories. Six mind-blowingly awesome half-stories, but they all need their closure, and they all get it in FoH.

The last two books are perfectly serviceable, but nothing to compare to the Hyperion Cantos. Ironically, I own all of them except Hyperion, I situation that I have to remedy at some point.

As I read _Hyperion_ and _Fall_ back-to-back, I don’t separate them out that much, though thinking about it, _Hyperion_ is far more distinct in my head than _Fall_. (And when I read _Ilium_ and enjoyed it, I never got around to _Olympos_, probably because of the questions-answers imbalance.)

The Endymion duology were two of the first books we said, “get these *out* of our house!” when we were purging our bookshelves recently.

The Hyperion stories are definitely the ones that, when I think about them now, make my fingers itch to go fetch the book down, but I liked the other three books too. I guess I read all four books when I was still in my pre-critical phase–whatever I read was simply accepted as it was and “author” was simply another word for “books like other books with that name on them.” I’m curious why the Endymion books are receiving such loathing, I guess, and I was wondering if anyone would be willing to explicate their dislike?

I actually liked the Endymion books. However, I waited about 6 months after reading the Hyperion duology to start in on those two. I don’t think I would have liked them if I read them right after Fall of Hyperion. I think Simmons is a wonderful writer. I really like how he draws on literary tradition. He seems to know a lot about literature and history and uses it heavily in his novels without making it feel like he’s lecturing.

I’m with Jo on this one.

What I took away form _Hyperion_ was that sex and death, for Simmons, are deeply crosswired.

The book makes the link about as explicit as possible. In the soldier’s story, for instance, the beautiful, mysterious woman turns into a monster at the point of climax (and was that /ever/ explained?). And in the consul’s story… well.

In fact, if you look a bit more closely, it’s in every single one of the tales: the Bikura are sexless but immortal, and they transmit their curse to the celibate priest. Rachel is stricken when she goes to Hyperion with her first lover. The Shrike’s first appearance onstage is murdering lovers in their bed. Brawne Lamia (ugh) has one fling with the Keats-analog, and then he’s killed; etc., etc.

It’d be nice to think this was completely deliberate on Simmons’ part.

Doug M.

I’m with Jo. Hyperion, then stop.

The fall-off in quality from the first to the second book (and I didn’t read the Endymion books, but the Ilium ones are pretty terrible, and let’s not even mention the time traveller short…) is severe.

Hyperion doesn’t have an ending that explains everything that has been going on, but it does have a very definite ending.

I find it very interesting just how many people disliked the Endymion books. Not only here, but among my own group of SF readers, with whom I compare notes. I felt that the twisting of the Church, the corruption of Hoyt by the Core, and the use of the missionaries sent by Dure to instead spread the insidious cruciforms to be a very approrpriate illustration of many of the mis-steps of the Catholic Church in our own history. The twisting of the entire universe, and the tie-in to the Messiah mistique without lessening the impact of Jesus was well handled, I thought. I can see where Cristians and Catholics alike would find the entire treatment to be anathema and sacreligious, however.

That being said, I actually read the original books in reverse order: Fall of Hyperion followed by Hyperion Cantos. It made for some disconnects in Fall, not having the back-story, but I also found that the back-story was much more comprehensible that way. I tend to recommend people to read Cantos, then Fall, then re-visit Cantos for a full appreciation. I then warn devout Catholics and Christians to avoid the Endymion books, unless they are secure in having their notions of orthodoxy challenged without taking it personally.

As far as the the Illium Duology goes, I though they were brilliant. But in a vacuum, they are tough to handle. Without the background of the Trojan War, without the background in the Tempest (which I needed to go back and re-read after I finished Ilium), the books are pretty tough to get into. The subtle nuances of the story are lost entirely. I also feel that the short story The Ninth of Av is a useful primer, though Simmons did deviate from some assumptions in the original short story when he expanded the concept for the novel. The one underlying theme that I thought he pulled off well was the animosity between Islam and Christianity, as the descendents of Isaac and Ishmael continue to war with each other long after the reason for the schism has been forgotten.

In many ways, I believe that Simmons is misunderstood as an author. He writes in whatever genre, using whatever tropes he needs to, to tell teh story he wants. But readers often make the mistake of assuming that the story goes no deeper than the genre (if that makes any sense). Much like the Dune chronicles, almost every one of his books is subtle in it’s references to MANY very diverse themes. The only exceptions that I have encountered have been Darwin’s Blade, and the Nails books, which truly are the fun romps they seem to be (though I admit that I have not read Song of Kali, Drood or Terror, so I can’t comment on these). In every other case, if one ignores the subtle nuance references to other works in the genre, to other themes below the obvious story, I can see wher ethe book would be much less enjoyable.

Okay, I’ll get off my soap box now…

re. the Ilium books, my problem was not lack of familiarity with the Iliad and the Tempest. It was that Simmons was completely dependent on them, for so little effect. (He didn’t go anywhere with the Proust name-dropping, presumably because he couldn’t think of a way to make Swann an action hero)

And, you know, this thing “The one underlying theme that I thought he pulled off well was the animosity between Islam and Christianity”?

This was not actually a plus point in the book, as I’m sure will come as a shock to everyone familiar with Simmons’ deeply nuanced take on Islam.

heresiarch @19: I guess my personal dislike of the Endymion books stems mainly from the fact of my (likely mistaken) assumption that these were continuations of the Hyperion Cantos and that some of the damn questions and mysteries raised there, esp. about the Shrike would actually be answered. That turned out to emphatically NOT be the case. I can appreciate the need to retain some mysteries in books…but given that the whole crux of the Hyperion/Endymion series revolved around the solution of the mystery of the Shrike, and that mystery was never even close to being solved, it was very frustrating. Also, as a Catholic I did find his use of the Church somewhat distatseful in Endymion, though I don’t think I’m unable to appreciate such things in a fictional context.

Also, with Simmons in general, I think that he is often given a bit more credit than he deserves. His allusions to other literature and cultural tropes are often very glaringly blunt…instead of a scalpel he uses a broadsword. I mean {Brawne Lamia} is the lover of a clone of Keats? Give me a break. Cute little robots that read Shakespeare and Proust and have witty conversations with each other? Bleh. His mish-mash of the Matter of Troy with the Tempest in _Ilium_ and _Olympus_ was also pretty strange and ham-handed I thought. There didn’t seem (to me at least) to be any real synergy or fusion of the material…it just seemed like Simmons thought both things were pretty cool, and hey why not write book with both of them in it? Also, let’s throw in some _Logan’s Run_ while we’re at it! Wheee!

Basically I think Simmons is a guy with a lot of high-end concepts that he ends up employing in a very low-end way when the writing hits the page. He doesn’t so much allude to other cultural/literary elements as he excises them whole from their source and plops them into the middle of an SF/horror/whatever story that he’s written. I guess it shows that he’s pretty well-read, but a subtle user of his sources he is not.

Ultimately I just end up being mildly disappointed with most of his stuff. It often seems to me that his books seldom live up to the potential of their concepts.

Rayc @@@@@ #25, oh yeah, that was the *other* thing, I found a short story in the _Ilium_ universe that left a really nasty taste in my mouth.

Hyperion and Fall of Hyperion are a single story and should be read together. Would you stop reading the Lord of the Rings after the Fellowship? That would be the same as stopping after Hyperion.

Oddly, I only found Hyperion brilliant *after* reading Fall of Hyperion. Without the sequel, Hyperion is just a good collection of short stories; nothing more.

I haven’t read anything else by Dan Simmons, so I can’t comment on his other works.

Wow. This is a great introduction to another book I haven’t read yet. My attorney had just recommended the Hyperion series to me last week. I appreciated the comments here warning against reading past “Fall of Hyperion.” So today, I went down to the Austin Public Library’s liquidation store and picked both of them up for a buck apiece. They had the others there, too, but I left them on the shelf.

Thanks for the heads-up!

Seth

EagleHatman@24, I am a Lutheran-flavored Christian. To me, “The Rise of Endymion” really brought the Reformation to mind. Simmons never says that Christianity is wrong, he points out the corruption in the church of the far-future. At the end, the church is brought back to its roots. I don’t find anything anti-Christian or anti-Catholic in that.

I loved Hyperion, but believe “The Fall of Hyperion” enhanced the story further. The second book was very spiritual and had a massive impact on me. For me, the two books are a single entity.

The third book was a totally pointless exercise and I refused to read the fourth. These were simply sequels when no sequel was called for.

Another vote for the Endymion books. I really enjoyed the story and I remember thinking about some of the ideas for a long time afterwards. To this day I’m still creeped out by the resurrection ships the Church used when they were in a hurry.

It’s interesting the way Simmons inspires strong love/hate comments, e.g. the people who loved “Hyperion” but hated the “Endymion” books.

As for me, I loved “The Rise of Endymion” but strongly disliked “Ilium” to the point that I was sorry I read it.

I have to agree with Goblin Reservation here. “Fall of Hyperion” is also awesome. It brings in new concepts (the “Omega point” idea about God being created at the end of the Universe and then traveling back through time…the war between the two near-omnipotent future Gods…), and has lots of awesome poetry references. And an awesome conclusion. Not as original a format as the first book, but well worth reading.

The “Endymion” books, however, do truly suck. They are a huge step back – no new ideas, lame flat characters. Simmons tries to do a Jesus myth, but his “nanotech lolita Jesus” is nowhere near as good as Heinlein’s “Marian hippie Jesus”…plus the “Endymion” books “retcon” a lot of the cool ideas from the first two books…argh!

Hyperion is one of my favorite SF books, probably in my top 5. I was blown away by it when I first read it. I do think Fall of Hyperion is worth reading, but I agree that the Endymion books were a bit of a letdown compared with Hyperion.

I offer a third path for this year-old comment thread:

The first Endymion book– society with cruciforms, Father De Soya, the abandoned web worlds, the introduction of Nemes– was terrific.

The second Endymion book– clunky writing, tedious papal politics, increasingly clueless and annoying narrator, increasingly senseless time-travel plot elements, lack of interesting resolution to many of the series’ mysteries– was terrible.

Sigh. Dan Simmons is the Dan Brown of science fiction. Hrothgar’s meadhall?

“a bit of Socrates’s Athens with the intellectual excitement of Renaissance Venice, the artistic fervor of Paris in the days of the Impressionists” ?

Beutifully written?? This is just like shoe-horning in the number of glass panels in the pyramid of the Louvre to show how prodigously well read and intellectual the author wishes he were. Amateurish, clumsily pretentious and annoying, this kind of thing should never be seen outisde of middle school composition classes, much less in one of the most widely acclaimed modern epics.

Several years ago – ten? – I found Carrion Comfort in a skip. I read and re-read this paperback version to the proverbial death until it finally disintergrated in my hands. Next up, during a brief visit to the USA, I found a copy of Summer of Night (why are Dan Simmons books so hard to find?) – well-written but too Stephen King for my liking. Last year, I purchased a copy of The Terror which was like living in a shroud of ice and horrible death for the three weeks it took me to finish it. Today, I finished Hyperion. I read it, one chapter/tale at a sitting and my partner always said I looked knackered when I rose from my chair and put the book down. As always, with any book I read, she asked me what’s happened and I always tried to explain but the picture I painted was always slightly incomprehensible though the strange fear in my face prompted her to ask me how could I sleep at night. I’m not an avid SF reader – Iain M Banks and John Wyndham being the only recognisable names in that genre for me – but the creation of a future universe in Hyperion and all its spiraling inconsistencies and hints of chaos, colonisation, the evil of humankind and the monster it unknowingly creates made it a great read. However, I never read books by the same author one after the other so it will probably take a year or maybe less or maybe more before I read The Fall of Hyperion.