Saleem Sinai, the first person narrator of Midnight’s Children (Random House), was born in the very moment of India’s independence in 1947. The conceit of the book is that he, and other children born in that first hour, have astonishing magical superheroic powers. The story is bound up with Indian independence, not just after 1947 but before—the story of how Saleem’s parents meet is one of the best bits—and how Saleem’s telepathic powers are at first a blessing and later a curse.

What makes it great is the immense enthusiasm of the story and the language in which it is written. It isn’t Rushdie’s first novel, that would be the odd and openly science fictional Grimus. But it has the kind of energy and vitality that a lot of first novels have. Rushdie’s later novels are more technically accomplished but they’re also much drier. Midnight’s Children is a book it’s easy to sink into. And the prose is astonishing:

I was born in the city of Bombay… once upon a time. No, that won’t do, there’s no getting away from the date. I was born in Doctor Narlikar’s Nursing Home on August 15th 1947. And the time? The time matters too. Well then, at night. No, it’s important to be more… On the stroke of midnight, as a matter of fact. Clock-hands joined palms in respectful greeting as I came. Oh, spell it out, spell it out, at the precise instant of India’s arrival at independence, I tumbled forth into the world. There were gasps, and outside the window fireworks and crowds. A few seconds later my father broke his big toe, but his accident was a mere trifle when set beside what had befallen me in that benighted moment, when thanks to the occult tyrannies of the blandly saluting clocks I had been mysteriously handcuffed to history, my destinies indissolubly chained to those of my country. For the next three decades there was to be no escape. Soothsayers had prophesied me, newspapers celebrated my arrival, politicos ratified my authenticity. I was left entirely without a say in the matter.

This is a very Indian book. Not only is it set in India, written by an Indian writer in an Indian flavour of English, but the theme is Indian independence as reflected the life of one boy and his friends. Even the superpowers are especially Indian, connected to Indian mythology rather than to the Western myths that give us the American superheroes. But it is also extremely approachable, especially for a genre reader. It was written in English (one of the great languages of modern India…) and by a writer steeped in the traditions of literature in English. Midnight’s Children is usually classified as a kind of magical realism, but Rushdie has always been open about enjoying genre SF and fantasy; he knows what he’s doing with manipulating the fantastic. The powers are real, in the context of the story. It isn’t allegory. There’s no barrier of translation here or problem with different conventions.

Midnight’s Children invites you to immerse yourself in India the way you would with a fantasy world—and I think that was partly Rushdie’s intention. He was living in England when he wrote it. He’s talked about how writers like Paul Scott and E.M. Forster were untrue to the real India, and with this book I think he wanted to make his vision of India something all readers, whether they start from inside or outside that culture, could throw themselves into. I don’t think his intention was to teach Indian history, though you’ll certainly pick some up from reading it, so much as to demonstrate the experience of being plunged into Indian history, as Saleem is plunged into it at birth.

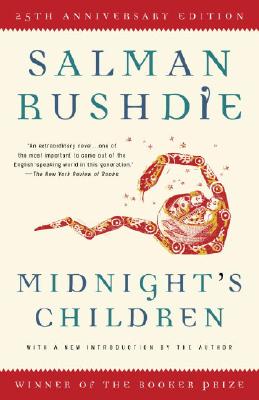

If it weren’t so brilliantly written, it would fall flat on its face. As it is, it has become a classic—it won the Booker Prize when it was published in 1981, and the “Booker of Bookers,” as the best Booker winner ever, twenty-five years later. It’s still in print and still being read, but largely as mainstream literature. It’s not much discussed as a genre work. I do think it has had influences on genre though, notably on Martin’s Wild Cards series. Both were clearly influenced by the comic-book superheroes of earlier decades, but I think the Jokers in the Wild Cards books, the people with minor useless superpowers, may have come from Rushdie:

The closer to midnight our birth times were, the greater were our gifts. Those children born in the last seconds of the hour were (to be frank) little more than circus freaks: a bearded girl, a boy with the fully operative gills of a freshwater mahaseer trout, Siamese twins with two bodies dangling off a single head and neck—the head could speak in two voices, one male one female, and every language and dialect spoken in the subcontinent; but for all their marvellousness these were the unfortunates, the living casualties of that numinous hour.

In any case, this is a delight to read, bursting with characters and description and the excitement of a whole real complex country sprinkled with magic.

*adds to wishlist*

And my list gets longer :) Thanks again for what sounds like a great book.

bluejo,

Dunno about influence on jokers, it is possible.

However, Edmond Hamilton’s Legion of Substitute Heroes and all the hopeless powers and weirdos from that were around about 20 years before that. A more likely example.

The Timing Thing is rather more like Rising Stars.

I WANTED to like this book but I had a really hard time with it. I reviewed it on my blog and found that some people loved it and others hated it. This was the only book I’ve read by Rushdie so far … any suggestions on another one to try?

Oh, hey! I read this book in school.

The main thing I remember about it was the protagonist’s nose (which if I recall correctly was given quite a lot of screentime, so to speak), but I think I was really distracted by other things when I read it, and didn’t give it the attention it deserved. I’ll have to go back and give this another try.

Brian Aldiss in an interview with ‘The Guardian’ a few years back stated that ‘Midnight’s Children’ was originally going to be marketed as a SF novel, like Rushdie’s previous ‘Grimus’. He was on the committee for a SF prize and ‘Midnight’s Children’ was going to win when they were informed by the publisher that they had decided to market the novel as ‘serious’ literature. As a result, as Aldiss observes, he went on to win assorted literary prizes, but almost certainly would not have been subjected to the fatwa after he published ‘The Satanic Verses’.

They’re both great novels by the way. Strongly recommended.

I just reread this recently, for the first time in a decade or so, and was astonished again at just how good it is. The verbal pyrotechnics are astounding, in a way he hasn’t quite repeated (though he may not have been trying in the same way), but completely and utterly in service to the story. Was it the reference in King of Morning, Queen of Day that led you to pick it up again?

(I also loved Rushdie’s latest, The Enchantress of Florence, in a way I completely didn’t expect after his previous two novels. Fairy tales, Machiavelli, and Renaissance India? I’m sold.)

Midnight’s Children was one very, very hard slog for me. I used to read it on the train from Streatham Hill to Victoria, and the journey (between 30-40 minutes) was just long enough to ensure that I didn’t give up forever because I could steel myself to read it for that long every day, but still a bit of a penance. I read it because my flatmate and friends from school were huge enthusiasts for Rushdie, but the thing that really got me was the style.

I once described it as “anchovy essence stirred into double cream” and, as chance would have it, found myself thinking of that description this weekend, before you posted, when I was whisking chopped anchovies into creme fraiche for a Jamie Oliver Chicken Caesar Salad, and I realised that anchovies and cream work very well provided you have enough other stuff – lettuce and chicken and bacon and parmesan and lemon juice – to balance the potential imbalance of flavour and texture. For me, nothing balanced the imbalance.

The opening paragraph you quote includes “Oh, spell it out, spell it out” and that particular stylistic tic really drove me mad – he does it again when he finally reveals who “the Widow” is and similar tricks at other parts of narrative and they’re all “Oh look at me! Aren’t I clever and post-modern? I’m a construct and you, dear reader are a construct and if you aren’t bright enough to play, well, you can always do the other thing.” Which was the deadly irony of the fatwa, of course: Salman Rushdie wrote a book which was on one level a bright, brittle, metaphysical game and it does not seem to have occurred to him that to play a game requires both consent and a shared understanding of the rules from the players.

Though I may be being hugely unfair; one winter’s night when cows had gone to sleep on the Ribble Valley line or we’d had the wrong sort of snow or something so the trains were out I found myself sharing a taxi back from Blackburn station (note the parallels of the train motif) to Manchester with three blokes one of whom argued very cogently that it is impossible to appreciate Midnight’s Children if you have never been to India, because sensory overload and wild confusion with conflicting messages is the point. So I’ve made a promise to myself I’ll somehow manage to get to India and then I’ll re-read and see how I feel.

I read this during my phase of attempting to branch out of genre reading into “literature”.

Well, “Midnight’s Children” qualifies doesn’t it? And I loved it.

@@.-@

I’d recommend Haroun and the Sea of Stories. It has a lot of the same magic and humor that his other books have, and it’s very accessible. After reading it, the rest of Rushdie’s work made more sense to me.

HeatherJ @@.-@, I’d recommend Haroun and the Sea of Stories first, because it’s brilliant, accessible, and fantastic (in the sense of “fantasy”, though both senses apply), then The Satanic Verses.

I think I need to reread Midnight’s Children. I read it years ago and mostly it convinced me that I know nothing about Indian history.

@10 & @11 – thanks, I’ll check those out!

Rushdie is one of my favorite writers, and Midnight’s Children is one of my favorite books. It’s a masterpiece, and I’m glad it’s being discussed here.

Slight correction; Midnight’s Children won the Booker Prize in 1981, the Booker of Bookers (best of the first 25 years of the prize) in 1993, and the Booker of Bookers II (best of the first 40 years) in 2008. (source)

I’ve read it several times; last time, I read the first half in Mumbai (those tetrapods he writes about? They are entirely real. You too can go and look at them today) and the second half on the train from Mumbai to Goa. It is one of my very favourite books, and that is one of my very favourite reading memories.

The Moor’s Last Sigh is very nearly as good.

Oh, dear. Midnight’s Children is a book I’ve always had problems with–I think I once classified it as “the greatest book I ever hated,” or one of the greatest books I ever hated, at least. It’s got all that energy, all that richness and wonder and invention and drive, and in the end I find Rushdie’s portrait of the world and (in particular) male-female relationships so unpleasant that I find myself trying to pick holes in the book. All the women are nurturing ball-busters, all the men are impotent rapists (which is quite a trick on both sides, when you think about it–takes a pretty remarkable writer to pull that off!) . . . and that’s only part of it. I know I’m being unfair, because the problem isn’t that I find Rushdie’s world or his characters unconvincing; it’s that I find it, and them, too convincing, too brilliantly written, and I’m afraid he’s, well, right about a lot of things that I would rather disagree with him on. Which is my problem more than the books, I suspect, but there it is.

One thing I’ve always wondered about sort of casually, though, and maybe those of you who know the book and its context better than I do can answer my question: given what Rushdie actually says about Indira Gandhi in the book, what on earth did the libel suit make him take out of subsequent editions???

Mary Frances @15[i}One thing I’ve always wondered about sort of casually, though, and maybe those of you who know the book and its context better than I do can answer my question: given what Rushdie actually says about Indira Gandhi in the book, what on earth did the libel suit make him take out of subsequent editions??? [/i]

She sued for libel? Well, I can’t say I’m surprised, though I hadn’t heard of it. Doo you have any details? Did Benazir Bhutto sue over Shame, do you happen to know? Of course, with both Ghandhi and Bhutto murdered by now, any stuff previously considered libellous could be reinstated if the publishers so chose.

legionseagle@16: Yes, Gandhi sued for libel. I don’t really know all that much about the case. I believe the suit was brought in England and that Rushdie settled out of court on the advice of his lawyers–and also that the changes were fairly minimal and relatively personal (rather than involving “the Widow’s” political actions in the book). Nor did Gandhi ever make any attempt to stop the book’s publication in India, apparently.

For what it’s worth, I did a brief google search this morning, and found a clip from at least one scholarly article arguing that Gandhi was disturbed mostly in the context of the strong tradition of “anti-widowhood” in Indian culture–the idea that widows who survive their husbands are somehow evil and/or promiscuous. I really should look up the whole article, one of these days . . . I don’t know anything about Bhutto and Shame, I’m afraid.

I love, love, LOVED this book. Read it for a Postcolonial lit class and because it’s so long we stopped about halfway to a third of the way into the book. But I finished it anyways, because I LOVED Rushdie’s rambling style. For people who haven’t read it and want to: just know that it is an incredibly dense book, but it is so worth it to read. And this makes sense, because it is of course the story of 60 years in the life of not one country, but three (and perhaps even four)–India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and perhaps Kashmir. I loved how a reference to an event can happen 200 pages before the event , and how Rushdie uses that to link together all the parts of his truly immense story. A true classic, in my opinion.

@8 – have you read Notes from the Underground? I’m curious about whether the narrator’s self-loathing and yelling at himself in that text is bothersome in the same way.

Thanks to all for your intelligent comments. I’m reading MC now, and it’s amazing and daunting at the same time. I’m pleased to find that others found it so as well. I’ve read some of his others and I find this one at the top of the heap of his creations, though who knows what history will bring? One of the most helpful comments,and one I mentally commented on myself,is the terrific assault on the senses that India must be (a bold statement never having been there) and how that is reflected in the style of the book.

A book written with ‘hundreds and thousands’

I’d read Tristram Shandy a few months ago and when I read Midnight’s Children, I had the strange sense that I was rereading Tristram in an Indian setting–a biography of a very ordinary person, written in the picaresque voice, lingering forever on minute details. Both stories devote hundreds of pages to the prenatal history of the protagonist. Both invite an allegorical interpretation, implying that the biography mirrors the historical experience of the time, but I see no contribution to better understanding of the times. Both include snide commentaries on the inadequacies of the major characters. Both introduce a few new ways of portraying the human mind in print– for Rushdie the innovation is stringing verbs together without punctuation or conjunctions. I hope this catches on because it is efficient and effective.

Above all, I love Padma and Mary Pareira.

This book blows. Totally.

After this torturous read, I now understand and appreciate why the Ayatolla issued a death fatwa against Rushdie.

I went into this book hoping to expand my understanding Indian culture. By the middle of the book, I felt nothing but disdain for India as well as the author.