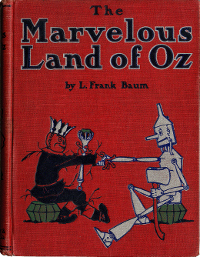

Buoyed by the unexpected success of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and brimming with hopes for additional revenue from stage and other adaptations, Baum rushed merrily into writing a sequel, The Marvelous Land of Oz. The result is one of the most seamless of the Oz books, with few of the digressions that litter the other books, and a rollicking farce.

And also, a rather problematic book for feminists. But we’ll get to that.

The Marvelous Land of Oz takes off more or less from where The Wonderful Wizard ended. Dorothy, though, is absent, and her place is taken by Tip, a young boy living not all that happily with Mombi, a witch. After he creates a pumpkin-headed man to terrify her, he finds out that she plans to turn him into a stone statue. This revelation makes him decide to run away with his creation, a now-alive Jack Pumpkinhead, straight to the Emerald City—and into a revolution.

Yes, a revolution. Seems some of the women of Oz are not all that happy with the rule of the Scarecrow, left in charge of the Emerald City at the end of the last book. As their leader, General Jinjur, coolly notes:

“Because the Emerald City has been ruled by men long enough, for one reason,” said the girl.

“Moreover, the City glitters with beautiful gems, which might far better be used for rings, bracelets and necklaces; and there is enough money in the King’s treasury to buy every girl in our Army a dozen new gowns. So we intend to conquer the City and run the government to suit ourselves.”

Which they proceed to do. Suiting themselves turns out to mean giving up housework, eating candy, and reading novels. Meanwhile, Tip and Jack Pumpkinhead join the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman and new characters the Sawhorse and the Highly Magnified, Thoroughly Educated Woggle-Bug on a quest to quell this feminine revolution. (Yes. They are all male.) Finding themselves defeated, they turn to another woman, Glinda of Oz, and ask for help. She rightfully points out that neither contender (the Scarecrow or Jinjur) has a particularly strong legal right to the throne, and instead suggests seeking out the real ruler, the young princess Ozma of Oz, kidnapped by the Wizard of Oz and given into the custody of Mombi the witch. Mombi reluctantly reveals that Tip is actually Ozma, disguised by a powerful magical transformation.

The contrast between this and the previous book is astounding. Baum is both more relaxed and in far better control of his dialogue, both snappy and often laugh out loud funny. Check out, especially, the first meeting between the Scarecrow and Jack Pumpkinhead, with its chatter about language. And Baum is at his inventive best with the new characters—the pompous pun-loving Woggle-Bug, the sullen Sawhorse, and the lugubrious but ever smiling Jack Pumpkinhead. (His smile is carved on, so it never leaves him, despite his constant fear of spoilage and death.) Less a fairy tale than a farce, it should be a guiltless pleasure.

But. The villains. Mombi the witch and Jinjur the revolutionary, who takes over the land of Oz so she can eat green caramels and read novels and use the public treasury for jewelry and gowns. The women rejoicing when Jinjur is conquered because they are tired of eating their husbands’ cooking. Jinjur’s Army of girls shrieking in fear over mice.

You could almost slam Baum for using such stereotypical images, not to mention throwing a satire on the U.S. women’s liberation movement into a children’s book, possibly to poke fun at his mother-in-law, Matilda Gage, a prominent suffragette. (She brought Elizabeth Cady Stanton to his wedding.)

Except.

Except that at the end of the book, in order to seize power and restore order and goodness to Oz, the book’s boy hero has to become—a girl. And needs the help of women (Mombi the witch, Glinda the sorceress, and Glinda’s all female army) to do so. His friends assure him that girls are equally nice, or even nicer, and make excellent students. (The prospect of studying does not appear to reassure Tip.)

It’s a powerful scene, so convincing that as a child I wondered uneasily if I’d once been a boy. And Tip’s transformation becomes the first step into a greater transformation for Oz—into a feminist utopia ruled entirely by women.

So I don’t exactly know what to think, except to note that as a kid, I turned to this book when I wanted to laugh. Years later, as a grown-up, I found myself still laughing. And finding that all that girl power at the end of the book does a lot to make me feel better about the middle.

Mari Ness continues to look for a pair of shoes or a flying Gump to take her to Oz. In the meantime, she lives in central Florida, under the dominion of two cats, who if they ever did reach Oz, would undoubtedly celebrate their gift of speech by demanding tuna. Like, right now please.

While I completely take your point about the un-feminist portrayal of the women’s revolution, I think that ultimately the transformation of Tip into Ozma is the more powerful of the two weird gender aspects of this book from 1904 (!).

I read the Oz books voraciously as a child, and I was completely nonplussed by the ending of this one. Here I was, identifying with the male protagonist, a young boy like me, and then he turns into a girl. Maybe this was actually less subversive at the turn of the century — maybe the idea of transgender was so far out of the mainstream that it just didn’t really register — but even when I was a child and had no idea that anyone might try to change themselves from a man to a woman, it was still challenging (and uncomfortable to me). Looking back on it as an adult, I think it’s the most subversive book I read as a child.

And let us not forget… there are stupid women who only care about frivolous things and have a mile-high sense of entitlement. For every Elizabeth Cady Stanton, there’s a Leona Helmsley out there. It’s not feminist treason to tell the truth.

I think people who fly into stiff-necked rage over something like General Jinjur in a kid’s book are far too ready to take offense and, moreover, missing Baum’s point entirely.

Marvelous Land will also be serialized starting next month by Eric Shanower and Skottie Young for Marvel Comics. It’s a follow-up to their lovely Wonderful Wizard of Oz miniseries, which concluded earlier this year and has just come out in a hardcover collection. The first mini featured gorgeous art in service of a really faithful adaptation of the book, and I think we can expect the same treatment for the second.

I find it very odd that in a childhood of voracious sf/fantasy consumption, I somehow never read the Oz books.

I shall have to fix that, even if years too late.

I reread those books many years ago when I was just starting to think seriously about my own rather non-mainstream gender, and I found myself completely captivated by the narrative of Tip/Ozma. The line about “If I don’t like being a girl, you must promise to turn me into a boy again” went straight into my .sig collection. I don’t think Ozma ever does yearn to be Tip again, though. It’s occasionally mentioned in passing that she used to be a boy and is a girl now, and people just sort of shrug and say “it’s a fairy country, these things happen” and move on… though in Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, the Gump’s head makes a strange cameo appearance and mentions that Ozma doesn’t like it to talk because it reminds her of when she was Tip.

I do occasionally ponder the differences between Tip’s personality and Ozma’s. There’s a pretty big shift there. Ozma never goes on adventures herself. While Tip was quite willing to lead an army, Ozma is passive and hesitant when confronted with the Nome invasion in The Emerald City of Oz (one of the more incoherent episodes). It’s hardly as though Baum was opposed to writing “venturesome” little girls; they’re everywhere! Maybe Ozma was just too powerful to unleash on the main plot arcs.

Rosefox: Ozma does go on adventures herself: I quite distinctly recall a time when Ozma and Dorothy were on a two-person adventure. They gave brains back to the flatheads? But perhaps that was in a later, non-Baum-authored book.

But you’re right that Ozma’s personality seems quite different from Tip’s. In particular, she seems much more composed and assured than he does. The sense I had at the time — and I haven’t gone back to reread this and determine how much of it was my youthful discomfort with having the male protagonist I identified with transform into a girl — was that it was less like Ozma was shapechanged into a boy, and more like Tip was created as a sort of container to trap Ozma in, and that they were essentially different people.

Leigh- shocking! Appalling! I hope you still find them enjoyable. I have very fond memories of my mom reading them aloud to me and my siblings as kids.

MBS- I always thought of it the same way.

Actually, the fact that Tip becomes Ozma, and does so with the help of female characters, does not undermine the sexist nature of the book. Instead, it reinforces it by holding up the image of “good” women (gentle, meek, nonthreatening, wielding what power they have in order to uphold the established order) versus “evil” women (disruptive, disobedient, wielding their power for their own ends). Patriarchy knows right well that it can’t really survive without women to do its dirty work, bear its children, and fill its beds (unless, I suppose, it’s that portion of the Patriarchy which blogs at The Spearhead); it therefore needs to find an acceptable niche for women, a way women can be subordinated and made to benefit the patriarchal order. So yes, there are women in Baum’s book, and yes, some of them are in positive roles, but sadly, the situation is not as narratively or ideologically complex and fascinating as it might at first seem.

The book with Ozma and Dorothy setting out together to stop the war between the Flatheads and Skeezers was GLINDA, Baum’s last Oz book.

Laughingrat:

Roles such as the main character of the whole series, the ruler of the country, and the most powerful magical being in the country? These are subordinate niches?

I’m sorry, but you’re off the mark here. Baum was a noted supporter of women’s rights, and while the General Jinjur stuff looks pretty sexist today, on the whole the books (even this one) were subversively feminist for his time.

Laughingrat: I’m confused by why you believe that Ozma is “gentle, meek, nonthreatening, wielding what power they have in orer to uphold the established order.” I’ll grant you “gentle.”

You also suggest that the patriarchy wants women to “do its dirty work, bear its children, and fill its beds.” Which of these do you think that Ozma (or, for that matter, Dorothy or Glinda or Tip or any other major female character with the exception of Auntie Em) does?

I had the Oz books before I read my first SF book. That was a magical land that you could go to and visit again and again. Unfortunately, in our many moves the original books were lost or destroyed but they not only were fun to read but gorgeous to look at.

I’m shocked, shocked that Leigh hasn’t read them.

A lot of feminists would argue that a woman who has to roar and bully and wave a knife or gun around to achieve her goals is tacitly admitting that women, as such, are worthless because reason and nonviolent methods of problem-solving are worthless.

I have had younger friends who got heavily into martial arts, and liked to brag about what they could do to a possible assailant. I’m all for fighting back, but bragging is tiresome, and it’s always saddened me how much of their idea of their self-worth was based on their ability to damage someone else.

I so need to read this book! When I was a kid, I didn’t read anything that had been identified to me as a kid’s book.

Also, the movie’s monkeys were terrifying.

Purely based on the discussion here, it sounds like Ozma’s post-Tip personality could be explained as the effect of having great responsibility. If she’s presented as a wise ruler, it seems to me that’s the most important comment by Baum. After all, the US has yet to give the highest office to a woman, or even a reasonable number of the major offices. Yet Baum was saying then that it would be good for a woman to rule.

@rosefox, @Michael B Sullivan, @nathan DeHoff – Ozma strikes out on at least two adventures – Ozma of Oz, where she’s joined by the rest of the Oz crew, and Glinda of Oz, where she and Dorothy head off into the wilds alone to attempt to prevent a war, in an almost certainly deliberate echo of Wilson’s appeasement attempts in early World War I.

In both adventures, Ozma needs to be rescued. Unlike Dorothy and Trot who generally manage to do their own rescuing. But – the fun twist – in both adventures, Ozma is rescued by women.

@leighdb and @willshetterly Yes, yes, you must read these books! I insist!

@Michael B Sullivan @1 – I can’t speak for other readers, but before I read this book, it certainly had never occurred to me that anyone could change genders – you were either a boy or a girl, and that was that. Learning otherwise made a tremendous and beneficial impression – and I’m glad I learned this when I was a kid.

Patriarchy stuff addressed in my next comment.

@Laughingrat

I’m not sure I entirely buy this patriarchy argument, for a couple of different reasons:

1. Glinda the Good may be gentle, but she is definitely a figure of awe and power – several characters throughout the book admit to being genuinely terrified of the Sorceress. (Since we later learn that she also keeps track of absolutely everything that happens in both Oz and the rest of world, including the non fairyland parts, we have some reason for the terror.) She also commands an army of skilled women warriors, and all of the books after the first strongly imply that one reason why Oz remains peaceful is because Glinda is enforcing that peace. It’s also fairly clear that although Glinda bows her head to Ozma in a token “ok, you rule,” sort of way, she’s clearly the most powerful person in Oz. In later books, the Wizard acknowledges her as his superior without hesitation.

2. “bearing its children” – Well, maybe, but not in Oz.

Oz is curiously devoid of sex. Almost all of the characters are happily and contentedly single, and most of the married characters we do meet (Aunt Em and Uncle Henry, the Crooked Magician and his wife, Jinjur and her husband [introduced later in the series], and Mr. and Mrs. Yoop [who don’t even live together] don’t even have children. Every once in a while the characters arrive at a farmhouse with a married couple with kids and get fed large meals, but that’s about it.

Later, Baum is absolutely explicit: no one ever ages in Oz, and more importantly, no one ever gets born. If people are having sex (and it can be easily argued, based on the text, that no one is), it’s certainly not for the purposes of procreation. This is for a very good reason: no one ever dies in Oz, either, which means that if people could have children, Oz would rapidly become overpopulated. (This issue is even addressed in Tik-Tok of Oz where Ozma points out that she has to be careful about allowing American visitors to stay in Oz, because she cannot risk having the country overcrowded, and once Americans arrive in Oz, they can’t die either.)

Admittedly, some of this lack of romance and sex stems from Baum’s belief that kids didn’t want romance stories, they want adventure stories. (This was true for me, at least.)

3. I’m going to be addressing this later, but, basically, no one – male or female – seems to do a lot of work of any kind at all. When we do see people working, however, this work, with the exception of Ozma’s maid Jellia Jamb, is not segregated into traditional gender roles.

So I’m not seeing a traditional patriarchy operating here, especially in the later books, where it’s very clear that Oz is run by women, and as @kagebaker notes, the women are choosing to rule with generally non violent methods (with the possible exception of Glinda’s standing army, which only comes into play in the second book.) And as others have noted, the books were, for their time (late 19th/early 20th centuries) subversively feminist.

I’m kind of sad Gregory Maguire has seemingly chosen not to introduce Tip/Ozma in his “Wicked Years” books; they present an Oz which one can actually take semi-seriously, and I think they’d have interesting things to say on the subject.

The abrupt change in Tip/Ozma’s personality, if not at the end of The Marvelous Land of Oz, then in the relatively short time between that book and Ozma of Oz, is a lot more disturbing than the surprising change at the end of The Marvelous Land of Oz. Not only changing sex but at the same time assuming adult responsibility as ruler of Oz can account for a lot of this, but maybe not all.

And Ozma indeed becomes almost too powerful to tell interesting stories about, after she acquires the Magic Belt at the end of Ozma of Oz.

The later Oz books are fairly inconsistent in their statements about whether people can age, get sick or die in Oz. Some (e.g., The Emerald City of Oz, where Billina mentions that one of her chicks died after taking cold) seem to say that only natives of Oz are immortal, while visitors and immigrants are in danger of death; some of the later ones (someone mentioned Tik-Tok of Oz) say that immigrants are affected as well.

I suspect that General Jinjur and her all-female Army of Revolt is more of a satire of the Susan B. Anthony faction of the women’s movement rather than of Baum’s mother-in-law Matilda Gage, who had been ostracized by Anthony (and who was dead by the time Baum wrote the Oz books). If any figure in Marvelous Land hints of Matilda, I tend to think it’s probably Glinda. And the conflict between Glinda and Jinjur (and their armies) can be seen as analagous to the conflict between Matilda Gage and Susan B. Anthony–but here the Matilda figure wins instead of being written out of history as in real life. I don’t know whether this view holds any water, but I think it’s food for thought.

The transformation of Tip to Ozma seems clearly meant to provide a trouser role for a pretty young stage actress to play the role of Tip and appear in a beautiful gown in the final scene. The book was written to be a stage show, to try to repeat the tremendous success of the Broadway Wizard. In the show–The Woggle-Bug–Tip is aware early on that he’s actually a transformed girl.

Funny, I’ve always found the “interpreter scene” between Jack and the Scarecrow to be really weird and uncomfortable. And as a kid, I didn’t understand most of the Woggle-bug’s puns. I think Wizard remains a much stronger book than Land. But of course, tastes differ.

As a kid, too, I wasn’t much phased by Tip turning into Ozma. There are plenty of transformations of characters in the Oz books. This one didn’t seem much different to me. As an adult, however, I can understand others’ reactions–from fascination to freaked out.

Marvel’s comics adaptation of Marvelous Land will indeed be as faithful to Baum as was the adaptation of Wonderful Wizard.

Sorry for taking so long to reappear here – real life and all that.

@17 Inkless I may be wrong, but I think Maguire references Tip by calling the missing Ozma “Ozma Tipperarius” or something like that. I remember chuckling a little over it.

I’d also say that Maguire so transforms the Oz landscape that I’m not particularly miffed at minor changes – I just enjoyed seeing all the little Tik-Toks around.

@18, Jim, I’ll be chatting a lot about Ozma’s personality in upcoming reviews, since she certainly changes dramatically from this book to the next, and continues to evolve in later books. (Thankfully. If the Ozma of Emerald City had stayed around I wouldn’t have finished the series.)

#19, Eric, first let me squee a little at finding you here :) I’m so looking forward to Marvelous Land.

Second, I saw some other elements clearly meant for the stage – the armies of girls easily turned into chorus lines, for instance. So it’s not hard to think of Tip/Ozma as a trouser role.

Both Tip and Mombi appear in the second Wicked book, Son of a Witch. The main character, Liir, crosses paths with them very briefly. I don’t remember whether they’re called by their names–I think not–but anyone who knows the characters will recognize them.

One thing I’ve found particularly hard to digest about this book and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is Baum’s description of landscapes. In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the grass over the countryside was green, the dirt was brown, and the ‘zones’ of Oz were separated by colors – blue for Munchkins, Yellow for Winkies, Purple for the Gillikins, and Red for the Quadlings. Well, when you get to this book, he describes it differently. Even the dirt and mud were the color of whatever country you were in, where as before, it was just what color your clothes, houses, or fences were painted and what color flowers you grew. This difference makes it hard to deal with continuity and I wish he’d taken notes or gone back and reread what he’d already done.

I don’t know, perhaps he was thinking it was just going to be a kids book and it wouldn’t matter… *shrug*

It’s really a shame that Baum never wrote another Oz book as clever, as witty, and as memorable as The Land of Oz. For once, he didn’t seem to be aiming the story directly at children; he seemed to be writing it to please himself. The result is absolutely delightful. You’re right, Maris, the book IS laugh-out-loud funny. It’s so good that, whenever I mention the Oz books to friends, I always recommend that they read The Wizard and The Land books first and foremost, so that they get a taste of Baum at his best. It’s a pity that the later books became, I’m sorry to say, so episodic and childish in tone; wit gave way to forced whimsy, and Baum’s determination to sanitize Oz robbed the land of much of its early gritty rural identity. But at least he wrote two really good books in his series. I think J.K. Rowling wrote only one: The Prisoner of Azkaban. The rest of her work reminds me uncomfortably of the gradual decline of the Oz series. Getting back to The Land, I really wonder why a movie hasn’t been made of it. I do know that a TV version was broadcast on The Shirley Temple Theater TV show (I actually remember seeing part of it – I remember seeing the Sawhorse talking, a very fuzzy memory). The Land would make a great movie IMO.

Some elements of The Marvelous Land of Oz have appeared in other Oz movies – Return to Oz, for instance, which I haven’t seen in years, but which I remember disliking because (in my opinion) it messed up the story without keeping up the humor. And my understanding is that some of the upcoming Oz film projects plan to use elements from the later Baum books – although, this being Hollywood, I suspect that’s subject to change.

I do think that The Wizard of Oz film is a hard act to follow – not just because of the catchy, memorable songs, or because it’s now a film icon, but because it really is a very good film. Any post Oz film that does a direct sequel, with or without music, is invariably going to be compared with the 1939 film, and while I have no doubt that an equally good film could be created, especially by using the Marvelous Land of Oz or (if the film wants to keep Dorothy as a featured character) Ozma of Oz, but I can readily understand why Hollywood producers might balk at the task, and try to do a “new” (and probably less interesting and more disappointing) take on Oz.

I don’t think the decline in the Oz series comes as much from Baum’s decision to focus on children as much as from his decreasing lack of interest in Oz, and resentment that his readers just wanted to read more about Dorothy. He was professional enough to continue to write, but not inspired enough to produce something as delightful, laugh-out-loud funny and well plotted as this one. It’s a fairly common reaction from authors, especially those creating iconic characters – the Sherlock Holmes stories, Hound of the Baskervilles aside, were never as good after Holmes miraculously rose from the falls as before.

This is long, long after the above conversations have grown cold, but I just discovered your commentary on Oz and Ozma, and now wish I had before I used Ozma as the Sorceress Character in my own Wearing the Cape series of stories. I’m not sure if your cogent observations and your reader’s comments would have changed my portrayal of Ozma, but they certainly would have helped my struggle with the character! Thank you.