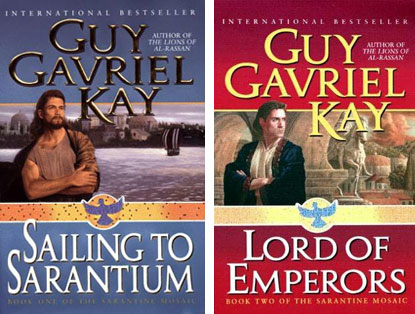

Your experience of reading Guy Gavriel Kay’s Sarantine Mosaic (Sailing to Sarantium and Lord of Emperors) is likely to be extremely different depending on how much you know about Justinian, Belisarius, and the history of sixth century Europe. There’s a way I never read these books for the first time—I was so familiar with the material Kay was using that it was like a retelling. If you’ve read more than one retelling of Homer, or of King Arthur, you know what I mean—it’s a case of interpretation, selection and shaping, rather than invention. There was never a time when I didn’t know the story to begin with, when I didn’t recognise who the characters were. And the characters are very close here—the map looks like a fuzzy Europe, and when I’m talking about the books and I haven’t just read them I’m inclined to forget Kay’s names and use their real names. Kay isn’t trying to hide the fact that Sarantium is Byzantium, Varena is Ravenna, Valerius is Justinian, Pertennius is Procopius, and Gisel is Amalasuntha. If you don’t know who those people are, your reading experience would be a discovery. If you do, then it contains a lot of recognition of how clever Kay is being. Yet Kay clearly expects a certain amount of real world context to intensify and contextualise the story he’s telling. You can enjoy the story without ever having heard of Amalasuntha or iconoclasm, but you’re expected to recognise Asher as Mohammed and appreciate the implications.

The question this demands is, if he’s going to keep it that close, why not write a historical novel? Well, the advantage of re-writing history as fantasy is that you can change the end. You don’t even have to change the end in order to get this advantage. Because it’s fantasy, because you have changed the names and reshuffled the deck, nobody knows what’s going to happen, no matter how familiar with the period they are. I realised this half way through The Lions of Al-Rassan with a shock of delight. Kay talks about respecting the historical characters by not writing about them directly, and the ability to make things clearer by purifying and condensing events and issues, and that’s also an advantage, but a historical novel is inevitably a tragedy, a historical fantasy is open.

I’ve worked out why everyone is so interested in Justinian and Belisarius. It’s because of Procopius, Justinian’s official historian. In addition to Procopius’s official history, in which he is deferential to hagiographic about the characters, he also wrote a secret history in which he vilifies them. The contrast is clearly irresistible. (Kay also couldn’t resist having Crispin punch Procopius/Pertennius in the nose, and I have to say I couldn’t have resisted it either.)

These are weird books. They’re written in an odd, distanced, elegaic style that I want to call veiled omniscient. The omniscient narrator knows what will happen, and what did happen, and what everyone thinks, but doesn’t like to approach too closely. He draws and lifts veils. He plays tricks where he described but doesn’t say who is who—does anybody like this? I hate it when Dorothy Dunnett does it, and I hate it here, too. If a blonde woman comes into the room, don’t leave me guessing who it is for two pages, this will not enhance my reading experience but rather the opposite. There’s a sense here that we’re always looking through the wrong end of the telescope, that these people are far away. Sometimes this makes for very beautiful writing, but there’s always a pulling back. There’s blood and sex and love and death, but they’re interpreted through the consciousness of artifice. It’s amazing that Kay makes this work at all, and it mostly does work. There are many points of view, but he never takes up a character just to throw them away. The ironic linking of everything together in omniscient connects and underlines and is sometimes incredibly beautiful.

What Kay does supremely well here is evoking the world, juggling the city and the empire, the neighbours, the gods, competing religions and heresies, chariot racing, factions, mosaics. The details are all real enough to bite, the varying quality of the glass tesserae, the mud, the fish sauces, the tool for drawing out arrows from flesh. The details are right for sixth century Byzantium, and even where he’s made them up they feel right.

Kay mediates the world through the chariot races and the making of mosaics, he often describes it in those terms. We get the heresy and the religion through the mosaics. We get life and control of the empire through the chariot racing—sometimes as a metaphor and sometimes for real. There’s a set piece race in each book, both different, both splendid. The pacing of events is unusual, it tends to concentrate on single days in which many things happen, with lots of flashbacks and remembering—there’s more use of the pluperfect tense in these than anything else I can think of. This single day thing is almost like Ulysses—there are a lot of characters, a lot of events, all compressed into a small moment of time. You’ll have a chariot race and see it from the point of view of a driver, someone in the crowd, an undercook for the Blue faction making soup.

The main character is Crispin the mosaicist. After a prologue set in Sarantium at the time of the accession of Valerius I, the arc of the book follows Crispin’s journey from Varena to Sarantium and back. We spend more time with Crispin than anyone else, and Crispin is more deeply embroiled in events than quite makes sense. This is fairly normal in stories with a protagonist, but odd in something so relentlessly omniscient. Crispin is so passionate about his mosaics that you can almost see them. And through the course of the books he makes an emotional journal come back from not caring about life.

There’s more magic than there was in The Lions of Al-Rassan, but not much for a fantasy novel. There’s an alchemist who embodies human souls in birds, and there’s a truly numinous encounter with a god. That’s amazing. Beyond that there are a few inexplicable flashes of flame in the streets and some true prophetic dreams. It’s not much magic, but it runs glinting through everything else like the silver threads in shot silk.

This is an incredible achievement, and it may be Kay’s greatest work.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

Ohmygod, I have to read these now! I didn’t know what period they were. Punching Procopius in the nose is so exactly right.

I do not even know how to describe the level of obscenity and innuendo the Secret History attains in the original language. We do not have words that obscene in English.

I need to read these again. I didn’t know the real-world stories at all – well, I did know it was Byzantium, but maybe that’s on the cover blurb?

I mostly hate that thing where the author doesn’t tell who the person is but says some details that are supposed to make you guess. And the reason why I dislike it is that I’m really bad at figuring it out, and it makes me feel stupid. Like in Murder Must Advertise – when I first read it as a teenager I didn’t work out for ages that Mr. Bredon was Peter Wimsey.

It’s interesting to see someone else note that “odd, distanced, elegiac” style, too. And not only is there very little magic, but it’s hard to see how the magic matters in the plot. Except as a reminder to readers in this world that it isn’t quite our world.

I felt like the odd style of these books made them feel like mosaics. Kay builds up the a story out of pieces which, individually, don’t have a lot of detail or character but which, put together, build up to a rich picture. I could never quite decide if this was on purpose, or a justification for a style that annoyed me half the time.

Hobbitbabe: I think the magic does matter here. The birds affect the plot, and not just the psychological plot, but the actual events.

Rush: These will not make you hate Procopius any less.

I first read these two roughly ten years ago when I was still in college. At that point I had no knowledge of any depth about the actual history that inspired the books. I still don’t, really. Fortunately I knew just enough that it was obvious which regions and religions Kay was drawing parallels to though not persons so much as their offices and archetypes.

I loved both books! This post reminds me that I need to get back through them stat. It seems I lost my copy of Sailing in a move long ago so I’ll have to fix that soonest.

If I had any real ambitions to a career as a novelist, Kay is one of the masters I’d work hard to learn from.

That odd, veiled omniscient style you describe so well is actually one of the reasons I love Kay’s writing – I accept it doesn’t work for other people, but for me it’s evocative in a way I haven’t found from any other writer. I’m not sure why; I think it’s something about the way it stands outside and inside the story at the same time that lets me appreciate the entire story, rather than being in someone’s head.

There’s a long section in Lord of Emperors which is one of the most bracing, bravura bits of writing I’ve had the pleasure of reading. Exhilarating stuff, practically left me breathless by the conclusion.

I find that the trickery fits into his various rifts on the mosaicist’s art, and how it applies to narrative and perception. We’re getting pieces, and trying to fit them together to a narrative, and when some pieces are withheld we only have a partial understanding of what’s going on — so he toys with that, zooming in on this, not quite fitting this together, while you know the omniscent narrator has it all in their mind’s eye.

I can see how it could be annoying, certainly. And he’s done it before, in other works. But here in particular, I liked it, as it reinforced certain themes.

Both these novels and The Last Light of the Sun strike me as very strongly being about art and storytelling, respectively. Something I’ve always appreciated about them, and about Kay’s work in general, is how thoughtful he is and how willing he is to weave a narrative around aesthetics and philosophical considerations without turning it into polemic.

hobbitbabe @2, re: Murder Must Advertise, and the plot device of not explicitly telling the reader that two characters are the same person — I think it works well there, and is well justified, as none of the other characters know Bredon and Wimsey are the same person until late in the story. At other times it feels gimmicky and wrong, in cases where the lack of identification only works because the reader is artificially kept ignorant by the text of something they’d notice in a moment if they were present for the events being narrated.

Detective stories tend usually to have either a first-person narrator who’s neither the detective nor the culprit — often the detective’s sidekick — or to have a somewhat distanced third-person POV, focused more on the detective than on other characters but not so close as to tell the reader everything the detective is thinking. If the author violates those POV conventions, usually they also violate the convention of having the narrator be reliable.

This is less of an issue in other genres, but there can be good reasons for it in other kinds of stories too — for instance, in one of the Latro books (I forget which, it’s one of the first two), Latro’s amnesia prevents him from figuring out that two people he meets are the same person in different guises, though the reader will probably figure it out in a few pages.

I do not even know how to describe the level of obscenity and innuendo the Secret History attains in the original language. We do not have words that obscene in English.

Procopius as a sixth century Malcolm Tucker?

As to why Kay doesn’t use actual names of actual historical, i.e. ‘real’ persons, he writes about this here in the U.K. Guardian Books Blog.

Hmm. bbCode doesn’t allow linking.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/booksblog/2009/aug/20/novelists-real-life-characters

Love, C.

@10

Your link:

Guardian Books blog

“I’ve worked out why everyone is so interested in Justinian and Belisarius.”

I always thought it was due to the influence of L. Sprague deCamp and Jim Baen — or rather, to Robert Graves’ Count Belisarius and Liddell Hart’s use of Belisarius to promote the strategic “indirect approach”, respectively.

Both Graves and Liddell Hart were veterans of the First World War, and perhaps the myth of Belisarius as the good soldier blinded by the uncaring autocrat had some additional resonance — Graves and Liddell Hart both wrote biographies of T.E. Lawrence.

Procopius’s Secret History is lurid, but not especially so by modern standards. I could easily make a similar compilation about the current U.S. Secretary of State and her husband browsing through the political blogs.

To borrow a phrase from Leigh’s Gathering Storm review, Belisarius is competence porn. (Well, maybe competence erotica. The deeds did happen, after all.)

Kay’s take on the story is wonderfully elegiac and so laden with the music of time that it’s hard to describe. It needs to be experienced, and it adds an overlay to the event to see, not only how it feels to the characters experiencing it, but how the ramifications extend forwards through all of history to come, all of time. (The chariot race in Lord of Emperors is particularly beautiful this way.)

I totally love these books (and didn’t know much about Byzantine history). I do appreciate the writing style. Last Light of the Sun and The Lions of al-Rassan are similar in tone. (I believe these are all loosely connected, being in the same alternate version of our world.)