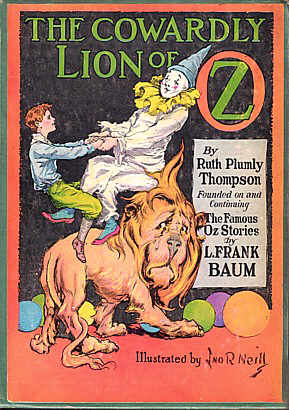

Some days, you just want one more little lion. Even if it’s the cowardly sort of lion.

Er, that is, if you happen to live in the land of Oz and already have 9,999 and a half lions already.

Before I go on though, I do need to say something about clowns. I don’t, as a rule, have particularly homicidal feelings towards clowns. I like clowns. When I was growing up, I had a little clown beside my bed to cheer me up and keep monsters away. So when I say something about the particular clown in this particular book, it’s personal, not general. Got it?

Because, trust me, this is one annoying clown.

Fortunately, The Cowardly Lion of Oz does not open with the clown. Instead, it starts with the irritated king of another of Thompson’s little Oz kingdoms (this particular one vaguely reminiscent of some imaginary Middle Eastern country) sulking because he doesn’t have enough lions. (We’ve all been there.) “Not enough” in this case means 9999 and a half lions (the front of the half-lion got away) and a very heavy lion tax, since although these may be magical fairy lions, they are hungry magical fairy lions.) Despite protests from his advisors and people, Musfafa demands another lion, like, right now. (Thompson assidiously avoids the issue of whether or not the current lions—excepting the half lion—are capable of having baby lions in the mostly static population of eternal Oz.) Specifically, he wants the most awesome lion of all: the Cowardly Lion of Oz.

Alas for the bad tempered king, Mustafa and his advisers are unable to leave their little country to find any lions, much less the Cowardly Lion, thanks to Glinda, here displaying more concern for lions than her general wont. Into this grave situation—well, grave from Mustafa’s point of view—tumbles, literally, a circus clown named Notta Bit More and an orphan boy, Bob Up, from the United States.

Initally, Mustafa and his court think that Notta Bit More is a lion.

You may be beginning to see the problems with the clown.

Ok. The clown. This post is not going to get finished unless I take a moment to explain the clown. His name, Notta Bit More, delightfully expresses exactly what I felt about him by the end of the book—NOT A BIT MORE. PLEASE.

The clown follows, he explains, four rules whenever he is in danger. One, try to disguise himself. Two, be polite—very polite. Three, joke. And Four, when all else fails, run away. And not at all to his credit, he follows these same four rules over and over throughout the book, leading to the same scene, over and over:

Clown sees, or thinks he sees, danger.

Clown puts on disguise.

People react with fear/anger/weapons/claws/large buckets of water.

Clown attempts to be polite to justifiably irritated/angry/frightened/distrustful people who are now in no mood for politeness.

Clown tells unfunny jokes.

People tie up or sit on clown. Readers wait in unfulfilled hope for someone to kill the clown.

I have no idea why the clown doesn’t try politeness, or even the unfunny jokes, first, instead of disguises. You would think that after two failed disguises, the clown would learn, but no, danger after danger threatens, the clown puts on his disguise, people hit the clown, the clown leads us through a series of progressively more annoying episodes, and…

It’s enough to make anyone hate clowns.

And if this weren’t enough, the clown also cheerfully and loudly plans to take every amazing person and talking animal he meets back to the United States—to make money by showing them at a circus. He seems willing to share the revenue—he continually reassures the talking animals that they can make piles of money in the U.S.—but seems completely unaware that a) showing off your new friends for money is icky, and b) the animals can only talk because they are in Oz.

Did I mention, enough to make anyone hate clowns?

I suppose it’s a natural attitude for some people, and the clown is hardly the only visitor to magical lands to have these instant wealth sorts of thoughts. Uncle Andrew, for instance, from one of the Narnia books, displays a similar attitude. But Uncle Andrew is a villain. Notta Bit More is supposed to be the good guy. And he has no problems with the idea of exploiting his new friends for fun and profit.

To add to this, he immediately plans to con a new acquaintance and will not stop his incessant winking. And it becomes unfortunately clear that he does not bathe too frequently.

I hate this clown.

Anyway. Mustafa, now justifiably irritated, and unconcerned with any resulting lion taxation problems, sends off the clown and Bob Up to capture the Cowardly Lion, giving them clear and precise directions to the Emerald City that absolutely anyone should be able to follow. Alas, he has not reckoned with the sheer ineptness of Notta Bit More, who manages to get lost almost immediately anyway by getting into a fight with the sign posts (they don’t like the clown) who instead send him to Doorways (they hate the clown).

Fortunately for Mustafa and the plot, the Cowardly Lion, by sheer coincidence, has just decided to leave the Emerald City to find courage that he can eat—literally. Detesting his cowardice, even after the Comfortable Camel explains that this is what makes him interesting, he has decided to follow the advice of the amoral Patchwork Girl: eat a brave person, and by swallowing that person’s bravery, become brave. (It says something that next to the antics of the clown this does not seem horrifying, but rather intriguing.)

The metaphysics of this seem slightly dubious, and the Cowardly Lion is aware of the moral complications (to say the least), but neither problem deters him. What does deter him: friendly, polite and undisguised behavior. (See, clown?) He cannot, he realizes, eat his friends, or anyone who is having a friendly conversation with him and asking for the latest in Emerald City gossip, however brave they might be. And then, he meets Bob Up and the clown.

For a brief shining moment, the Cowardly Lion almost—almost!—eats the clown. Alas, this marvelous moment is deterred when the Cowardly Lion realizes that this is one cowardly clown, and not likely to be of much use in any eating bravely diet. They somewhat inexplicably decide to join forces, the clown carefully and irritatingly failing to mention his plans to capture the Cowardly Lion and turn him over to Mustafa, Bob Up carefully and only slightly less irritatingly failing to mention his growing concern over the clown’s unstoppable use of disguises, and all three uncarefully landing into more adventures. From this point, the book moves at a nonstop pace, with a visit to the skyle of the Uns (they really hate the clown), the Preservatory (they seriously hate the clown), the Emerald City (they are rather dubious about the clown), and Mustafa’s kingdom (now too worried about a stone giant juggling the 9999 now-turned-to-stone lions to worry much about the clown) before the now traditional happy ending and party at the Emerald City.

And, yes, more Ozma Fail, as our girl ruler, caught playing checkers instead of ruling, is unable to see through disguises, prevent a clown from kidnapping the most important members of her court, or transform the Cowardly Lion back from stone. Oh, Ozma.

Oh, and in an inexplicable turnaround from her earlier anti-immigration stance of previous books, actually offering both Bob Up and this clown permanent homes in Oz.

I cannot fault Thompson for getting this characterization of the Girl Ruler so spot on. Nor can I fault her for the book’s tight plot and rapid placing, or to holding to her theme of Be True to Yourself. Nor her images, ranging from the mildly grotesque (pre cooked geese flying through the sky? Seriously?) to the utterly lovely (the dreams that arrive in delicate silver packages), cannot be faulted either, nor her delight in wordplay, apparent throughout. Nor can I criticize her for taking a moment to consider some practical problems with living in a fairy land where hot chocolate grows on trees. (Picking it improperly can create a terrible mess.) Or for taking the time to spell out serious concepts about identity, disguise and honesty, a message delivered by the Comfortable Camel midway through the book and repeated by Ozma and the Scarecrow later. The very need to spell these messages out, even after the clown has so eloquently demonstrated the problems of disguise, weakens their impact, and gives the book a decidedly preachy tone, but Thompson has the good sense to lighten the messages with humor, if not from the clown.

But I can fault her for creating a “good guy” that is decidedly not a good guy. I found myself resenting that, for the first time ever, I actively hated one of the good guys of Oz, and worse, one welcomed, like the Shaggy Man before him, into Oz. I suppose I should credit Thompson with recognizing that the generous Ozma is willing to overlook many things. The Ruler did, after all, welcome the Shaggy Man even after he confessed to theft. But the Shaggy Man at least reacted to Oz with admiration and love. The clown reacted with greed, deceit and thoughts of money. And even if money was the reason why Thompson was allowed to write Oz books, and why I got to read more of them, this is something I have difficulty forgiving.

Mari Ness likes clowns. Really, she does. She even wanted to join a circus once. She lives in central Florida.

My goodness.

There are some seriously peculiar moral messages embedded in these books, indeed.

@katenepveu

This is the first Oz book that I would hesitate to give a child. (Well, maybe the second, because The Royal Book of Oz just isn’t that good.)

I do think that the Oz books have some powerful, and beneficial, moral messages that I can agree with. I like, for instance, their insistence on not judging on appearances and the messages of acceptance and tolerance.

But the more I go through these books, the more it becomes clear that although Thompson clearly admired the idea of Oz, she and Baum had some fairly fundamental differences in their overall belief systems. Oddly, it’s Baum, the man born to a well-to-do family, who took the more egalitarian approach, and Thompson, the single working woman and support of her family, who tended to focus on social and gender differences. I’m not entirely sure yet if this is because as a woman, she saw them more clearly (possible, despite Baum’s close relationship with prominent 19th century American feminists – he was still a man), or if this is because she fundamentally agreed with some of these more constricting social systems. And I think it’s that conflict that leads to some of the peculiar moral messages – this gets even more complicated when we hit The Hungry Tiger of Oz.

Another major problem, though, is that Thompson’s better Oz books tend not to include familiar Oz characters – whenever she dragged in the major Oz characters, she tended to have more problems. We’ll be seeing this in future books as well.

@MariCats

First of all, I just want to say that I wanted to read the Oz series for a long time, but your reviews really sold it to me. I’m only at the fourth book, Dorothy and The Wizard in Oz, but I consider myself a fan already.

So here I am, wondering if I should read the Thompson’s books after I finish the Baum’s ones. You see, I live in Brazil, where only the first Oz book has been translated, so I have to order them trough Amazon, which ends up being quite expensive in comparison to what I would expend on a book bought here, and they take more than a month to get here. And it seems to me, from reading your reviews and some others around the internet, that Thompson’s book wouldn’t be worth all the trouble. It’s the same scenarios, sometimes same characters, but the feeling doesn’t feel like the same I have when reading Baum’s book (again, I’m saying this having never read a Thompson’s Oz book).

So, If it’s not too much to ask, can you tell me why should I bother with Thompson’s version of Oz? Is it something I would really miss on if I stop reading at Glinda of Oz?

@LukeOzBR

I was a bit worried about this exact concern when I started the Thompson part of the reviews, and I probably should have been more clear. The chief problem with Thompson, and the problem I had with these rereads, is that she’s the exact opposite of Baum in one major respect: her Oz books generally started weakly and got stronger as she continued, while his Oz books generally started strongly and got weaker. I like many of the early Thompson books (ok, I didn’t like this particular one because of the clown) but I don’t think they get really good until later on.

This is a serious problem, since most readers tend to read the books in order, and to be honest, if I had not read Pirates in Oz before The Cowardly Lion of Oz, I probably would have stopped with this book. I have a feeling that many people do that – one of the comments on my post about The Royal Book of Oz brought up the very legitimate point that the commenter hadn’t bothered to read more Thompsons beyond Royal Book because that book wasn’t very good. And unfortunately, in my opinion, it took her four Oz books to get to where she was exploring some of the same questions Baum was (I think Grampa in Oz is pretty good) and another few books before she really allowed her imagination to soar, allowing her books to take off.

So the answer to your question, especially given the financial concerns, is that it really depends upon _which_ Thompson you are talking about. I think some, perhaps many, of the later Thompson books are as good as the first 14 Baum books, and are worth all the trouble. Unfortunately, it’s going to take a few more posts to get to that point.

And, although it isn’t a Thompson book, I do highly recommend Merry-Go-Round in Oz, the last of the Famous Forty, which is one of my all time favorite Oz books.

One other note: The Tor.com store has several of the Thompson books for sale here:

http://store.tor.com/component/catalog/search?limit=20&search=Ruth+Plumly+Thompson