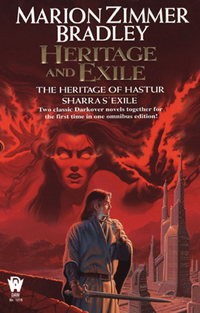

The Heritage of Hastur (1975) is a passionate novel of awakening love, sexuality, and magic. It’s set ten years after The Bloody Sun and two generations after the other Darkover books I’ve been discussing. It’s the story of two very different young men who are heirs to Domains on Darkover. Regis Hastur is fifteen, fully Darkovan, heir to Hastur, but he lacks laran, the magical gifts inherent in his genes. He hates the way he has to go through all the steps laid out for an heir, and he longs to leave his planet on a Terran spaceship. Lew Alton is ten years older. He’s half-Terran, or actually a quarter Terran and a quarter Aldaran, not that that helps as the Aldarans are hereditary enemies. He has lived all his life in the shadow of his father’s ambition for him—everything his father has done for years has been in the service of getting Lew acknowledged, accepted as heir. Lew has been forced along the same path that’s being laid out before Regis, but he’s had to fight every step of the way. Regis wants to escape, and Lew wants to be accepted. Neither of them gets what they want.

All the Darkover books stand alone very well. This would almost certainly be as a good place to start the series as any. It’s a powerful book, but very dark. All of it seems to happen at night, and with everyone either miserable or with their happiness overshadowed by knowledge of misery to come.

Isilel has a comment on the Forbidden Tower thread that is very relevant here:

When read in internal chronology, every multi-volume storyline is a tragedy, really, because every development runs into sand…. I used to read a lot of Bradley’s Darkover, haphazardly, but once it became clear to me how utterly futile anything achieved in an individual book turns out to be and that happy endings are basically lies, I abandoned it.

This is undeniable. Each book seems to have a positive ending, but nothing comes to anything. Technology does not change, attitudes do not change, the only thing that changes is that there are fewer and fewer people gifted with laran in each generation. This is especially noticeable here because we have the plot centered on Regis’s supposed lack of laran and the plot centered on Lew’s attempt to work with Sharra. Some things have changed—there are matrix workers outside the towers in The Bloody Sun, and nobody can work in a tower for more then three years now. But everything else goes on the same, or rather is reset to the status quo.

The book alternates between chapters of first person Lew and chapters of third person Regis. I don’t expect it’s the first book ever written to do that, but it’s certainly the first book I read that did that. I wasn’t put off by it, but I remember thinking “Are you allowed to do that?” The two stories interlock very well and feed into each other, so that even though there are two distinct character stories they are both part of the one big story.

There’s a theory of writing which I have only heard about by repute (but this seems to be a good statement of the system), in which you alternate scenes, in which things happen, and sequels, in which the characters reflect on the action. I find this quite horrifying as a way of writing, but I found myself thinking about it with regard to the Darkover books. There’s a way in which The Shattered Chain is all scene and Thendara House is all sequel, and again with The Spell Sword and The Forbidden Tower, in both cases the second book rests in the consequences of the actions in the first book. And The Bloody Sun is clearly sequel to the story of Cleindori. What we have here is an unusual case where Bradley had written the sequel about the consequences, and then wrote Heritage of Hastur to stand before it.

The original sequel was The Sword of Aldones, and then she rewrote it as Sharra’s Exile. I think Heritage of Hastur benefitted from knowing where it was going, and gains a real sense of tragedy from that. This is a tragedy. There isn’t any faked happy ending, this ending is clearly a patch-up on disaster, and the book is better for it. I’m not going to read Sharra’s Exile—or Sword of Aldones, not that I could. I’m not going to read it because it’s too depressing and I didn’t commit myself to a thorough or a sensible consideration of the whole series. But if you want to talk about it in comments here, do feel free.

Let’s talk about Lew first. Lew wants to belong, and he’s gone along with everything up to the point where they try to find him a wife. He then goes to Aldaran on a mission and gets caught up in a criminally irresponsible attempt to use the Sharra matrix. There are a whole pile of reasons why this is a terrible idea. First, Lew is the only one who is trained. Second, Sharra is an unmonitored matrix. Third, he’s using it outside a Tower. Fourth, Kadarin is very strange, probably non-human, and much older than he looks. Fifth, Thyra is certainly a quarter Chieri, a wild telepath and completely mad. Sixth, Rafe is twelve. Seventh and last, Sharra has been used as a weapon and wants to kill kill kill and destroy everything with fire. The circle they form in The Bloody Sun is bad enough, but this is madness. Never mind that a five year old child could see that this is a terrible idea, Lew’s horse should have been able to tell.

I like Lew, and I appreciate his personal problems. I think he was undoubtedly a fine technician in Arilinn, and he was definitely a good Guard officer, we see him being one in Regis’s point of view. He’s brave, he has a lot of skill, and he’s been pushed around too much by people with their own agendas, especially his father. But he should stick to following orders because he has absolutely no sense. Marjorie, his right arm, and the city of Caer Donn were a small price to pay for being that stupid. The book ends with his leaving Darkover—I think this is the only book that has an end like that. I remember him being no less idiotic in Sharra’s Exile, that’s part of why I’m not reading it. I like you Lew. But you need a keeper, in any sense of the word you choose to take that.

We’re always being told how dangerous the matrix weapons are. But this is one of the few books we we actually see one do anything. The Compact that limits their use—or the use of any ranged weapon—really is a good idea. I don’t think it would work as well as we see it, though. And the implication is that it is war alone that drives technology.

Regis’s story is about growing up, and though Regis is ten years younger than Lew he is in many ways more grown up. He’s repressed his laran and his sexuality, he rediscovers control of both of them. This is well done, and it was unusual to have a positively depicted gay (or bi) character in a SF novel in 1975. (It’s worth noting that this is the earliest-written of the books I’ve been re-reading.) The early books were adventure stories and either had child protagonists and no sex or very standard and chaste romances. I think this was the first one to have a gay character—and he doesn’t come to a tragic end. I think he sensibly has to count as bi because he does eventually marry (in later books) and have children but he always remains in a close relationship with Danilo and it seems quite clear that men are his preferred sexual partners.This is the story of a gay teen in a fantasy society coming out, growing up, and accepting what he is and his responsibilities to his planet. I’m impressed with it.

It does, however, leads me to the most problematic aspect of this book—Dyan Ardais. Dyan is Regent of Ardais for his mad father, Kyril who is old but still alive. He has unquestioned power, and he abuses it. He’s also cadetmaster in ther Guards, a post we’re told he’s sought and can’t be denied for political reasons. Lew hates him, but isn’t under his control. Regis and Danilo are. He’s very nice to Regis, who is a social equal, but Danilo is the son of an old family fallen on hard times, and Dyan can safely abuse him. He tries to seduce Danilo, and when Danilo rejects him he uses his laran to persecute him until Danilo loses control and attacks him, whereupon he’s cast out of the cadets. Dyan is a sexual predator on young boys—Danilo is fourteen. That Danilo is attracted to Regis (fifteen) and has a relationship with him later makes absolutely no difference to Dyan’s repulsive behaviour, any more than it would if a woman teacher in her forties did this to a boy of fourteen, or a man to a girl. Dyan’ is in a position of authority and he abuses it.

Most books would unquestionably treat Dyan as a villain. And Dyan is a villain here, but he’s far from a one dimensional villain. He has a deep level of psychological realism—not only his terrible upbringing, and the same weight of expectation that causes Lew to trash Caer Donn and Regis to want to flee the planet. He’s an incredible snob, more so than anyone in any of the books he believes in Comyn privilege and power. But he’s not only complex, he’s sympathetic and attractive.. He has the virtues of his flaws, he’s brave and honourable in what he considers to be honour—which of course doesn’t include being respectful of the physical or psychological integrity of his social inferiors. He behaves well in the end, making amends to Danilo and adopting him as his heir. Danilo, Regis and Danilo’s father forgive him for the earlier telepathic rape I mentioned how unusual it was to see a positive gay teen coming out. How much more unusual to have an even semi-positive portrayal of a gay sexual predator. I don’t have any problems with seeing Dyan as realistic—I have problems with wanting to see him punished. Adopting Danilo seems to me like the end of Measure for Measure.

Family Tree Trivia

Lew is the son of Elaine Montray and Kennard Alton. He’s the grandson of Wade Montray with a random Aldaran woman and Valdir Alton and Elorie Ardais. So he’s the great grandson of Montray the idiot Legate and his presumed wife, two random Aldaran people, Esteban Alton and his Ridenow wife, and Rohana and Gabriel Ardais. There are real people whose families I don’t know so much about. Indeed, there are very few real people whose families I do know so much about and most of them are related to me.

Regis is the great-grandson of Lorill Hastur, Leonie’s brother.

Dyan is the son of Kyril Ardais, who we last saw pawing Jaelle in The Shattered Chain, and therefore grandson of Rohana and Gabriel. He’s thus Lew’s first cousin once removed.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

“How much more unusual to have an even semi-positive portrayal of a gay sexual predator.”

The author was married to a gay sexual predator.

Assuming the book was written around the time of publication — 1976? — they’d been married for well over a decade at that point, and were still several years away from their eventual separation.

Walter Breen seems to have had a wide range of relationships with underage boys, ranging from “looks like consensual from the outside, albeit with great imbalance of maturity and power” through “psychological intimidation and manipulation of someone much too young to resist” to “pretty much rape, plain and simple”.

There’s considerable disagreement about Bradley’s level of awareness of, and consent to, her huband’s activities. But there’s no question she knew what he was. So I think we can reasonably assume that she drew on her experiences with him in developing the character of Dyan.

Doug M.

Oddly, Sharra’s Exile was the first Darkover novel I read. It’s a terrible place to start in so many ways, as too little of the world makes sense if you have no background. And yet, that mimics the experience so many of the Sharra circle are having. The plot is just like watching an intermediate skier take the advanced course–all downhill, too fast with too little control. I vaguely remember reading the whole thing in one sitting and then running out to find other Darkover novels just to try to understand what happened. In that sense, it was the perfect place to start. If I’d started in a more logical place, I think I’d have said “meh” instead of “OMG, more now”. Much of the impetus was that I too like Lew, and there is no excuse at all for most of his actions. The Heritage of Hastur takes some of the edge off that–not much, but enough.

Susan: presumably, as Sword of Aldones is where the series started, that’s where Bradley started and a lot of readers too.

When you say

it sounds a bit like you’re confused about the real-world chronology. Sword was one of the first-written Darkover books. A decade later, Bradley decided to write about the Sharra Rebellion, and ultimately decided that it wouldn’t work to be bound by the ideas of her younger self. So she wrote a very different story (with a little hand-wave in the front matter about Lew Alton’s memories having been blurred) — I don’t think she knew where it was going except for there having to be a “Sharra Rebellion” ending in disaster. Bradley then (perhaps influenced by fan pressure) rewrote Sword as a genuine sequel to Heritage.

I remember that Sharra’s Exile was one of the first Darkover books I bought when it was new, as opposed to picking up years after publication, so it’s definite in my mind that it came after Heritage was published.

I had an odd view of Regis’s plotline when I first read the book. We’re supposed to see him as young and vulnerable, but I was only 11 or 12 at the time: he was older than me. Fifteen seemed quite a mature age.

David: I haven’t read Sword of Aldones, but I bet I know what happens in it, though I could be wrong. In the note at the beginning of HoH Bradley says that there are inconsistencies and maybe Lew (as narrator of SoA) had mercifully forgotten some of it, so I assumed the main events of the tragic ending — Sharra rebellion, Lew losing hand and leaving planet — were firmly in place when she wrote this volume.

I was in fact aware of the chronology, I’m sorry I wasn’t clear.

As a complete aside, I don’t think Scene/Sequel writing is as unfamiliar to you as you might think :o). It may not be consciously deployed in your (excellent, what I’ve read of it!) fiction, but the theory has two primary parts:

Scene – Goal meets conflict and ends poorly WRT the goal.

Sequel – Reaction to the going-poorly creates a conflict for the character, who must choose how to react. (sets a new goal)

It may be death if you try to write to it, but most writing that doesn’t spend pages and pages in the character’s head does tend to stick to it.

As an example, from the opening of your very-enjoyable _Farthing_:

Chapter 1:

Lucy is trying to make herself presentable (goal)

David comes in, all verklempt. (conflict)

Lucy tries to soothe David and keep grooming herself, but he won’t be soothed (disaster)

She abandons her attempts with her hair (reaction) and in the ensuing discussion, acknowledges that she can’t tell him everything about her motivations for marrying him (dilemma).

We have a flashback where she thinks about this – complete with goal (convince Daddy it’s okay) and conflict (it’s not okay)… and, because it’s a flashback, we cut away before the rest… because him saying “okay, then” would just be boring, particularly since she’s married to him and obviously he did say okay.

And then we’re back to the main timeline, where we have a Decision – she shelves the thoughts as unproductive and finishes her hair so that she can go forth with him to the party, hand in hand and looking beautiful…and sticking a fork in the eye of those who she thinks deserve it.

That’s my read on Swain and your ch1, anyway.

Now, did you think through “I need to have her thinking something here!” as you were writing and revising? Probably not. But it’s a normal progression of things, and that’s what, I think, Swain was trying to get at.

-j

I haven’t read either book in a couple of decades, but my recollection is that Sword was really quite bad. It was basically Bradley managing to reshape and repurpose her teenaged Chambers fanfic. Dyan Ardais is much less honorable and much more villainous (I’ve read that he was a conflation of no fewer than three villainous characters, which perhaps left him less room for complex characterization).

I don’t remember the details of the plots at this juncture, but I do remember they were more different than you might think from having read only the one. Sword is really only of historical interest, I can’t at all recommend that you read it for pleasure.

(Did the stuff about Cherillys’ Law and everyone having a double survive into Exile? I honestly don’t remember.)

David: Yes, that’s in there. And in Two to Conquer too.

Blue Beetles: I’m not saying people don’t ever write anything that unconsciously fits that pattern. I just think that trying to teach people to write by thinking about that crap instead of the story is likely to produce things that feel utterly forced. Which isn’t to say that it isn’t a great method for some people who need to be thinking about that.

It’s been a very long time since I read HoH, but what I remember (or think I remember) is that this was the book where plot and characterization came together perfectly. Before HoH the books were pulpy, plot-driven, and the books afterward spent too much time on characterization, but this one seemed just right. It was interesting watching a writer’s development like this.

Bradley actually wrote a whole novel around the concept of doubles under Cherillys’ Law — Two to Conquer, one of the Ages of Chaos novels, where we get to see those laran weapons in use, and just how and why the Compact was forged originally.

Dyan in Heritage of Hasture is one of the best examples I’ve ever seen of well-done villains — a lot of people whose works I’ve run into could have learned from that portrayal.

Jo,

Well, that’s interesting. I read Sharra’s Exile about thirty years ago when what was on the local bookstore’s/library’s/used bookstore’s shelves was all you’d ever know existed, and I stopped reading Darkover novels about the time the internet began offering reference utilities. I don’t think I ever knew that the series began with Sword of Aldones (which I’ve never read).

Are you going to cover Stormqueen! ? (Sorry about the wonky punctation–the ! is unforgivably part of the title.) There you get to see the big-ass matrixes (matrices?) in action and, you can argue, the “ineluctable decline” argument breaks down, since the Comyn do, in fact, stop breeding for laran as bloodlessly, and put the Compact in place (that’s the law that keeps anyone from using a weapon that’s outside arm’s reach of an opponent).

The Compact has always seemed incredibly implausible to me, but it seems to work on Darkover.

I started with this and Sharra’s Exile! For a bi closeted teen, reading about Regis was awesome. And Dyan–oh yes, a very realistic, three-dimensional “villain” (in quotes ‘cuz he’s not so simplistic; I wouldn’t even call him a villain). Complex gay/bi protagonists and antagonists–yay!

I forgot about the alternating first/third person. It didn’t bother me at the time–perhaps she just did it very well, or I was so young. ;-) In contrast, I found that style very contrived and annoying in Lian Hearn’s Tales of the Otori series. (It didn’t help that I hated the female protagonist in that series, while I liked Regis and Lew a lot.)

Anyway, aside from one thing at the very end of Sharra’s Exile that confused me at the time (why/how a major character died–as a kid, it read like it was from rejection; still reads odd to me), these two books might be my favorites of the Darkover series. I don’t know if they’re really the best, or if it’s just that they drew me in and addicted me to the original series and so I remember them most fondly.

Maryaed — I’ve done a post on Hawkmistress which may be up later today, and there I stop. I did think about reading the other Ages of Chaos books, but I’ve had enough Darkover for now. Sorry.

Sharra’s Exile was the second Darkover novel I read, then The World Wreckers, the The Heritage of Hastur.

And I have to say – give me a honest tragedy, rather than those misleading “happy endings” that don’t mean anything and get reset in the next installment. Tragedies have become so rare in fantasy and even SF that each one is a breath of fresh air in a generally far too predictable genre.

That’s why I also have a soft spot for the The Storm Queen, despite it’s problems. That and the use of laran for motor-less flight, which was just the coolest image ever.

Even the setback from where The Bloody Sun seemed to be heading didn’t bother me at the time, because, well, setbacks happen. It is only when it became clear that the Darkover cycle is one giant setback/reset that I got fed up.

I also expected great things from that program they started in The World Wreckers, although all these Terrans having laran first made me wonder how exactly Darkover could suffer from the shortage of matrix technicians, particularly with numerous illegitimate offspring of the Comyn thrown into the bargain…

Wow, I never read this – but now I really want to. Especially because of the teen gay character in a sci fi book – wow – I had no idea this was out there! Shame about the sexual predator character… Makes me think of Baron Harkonnen in Dune, but he was just pretty much evil, wasn’t he? thanks for your great review – I’ll put a link to it when I list this book at my site!

Namaste,

Lee

“I’m Here. I’m Queer. What the Hell do I Read?” at

http://www.leewind.org

Ah, Regis Hastur, the very first gay character I ever read about. I am still kind of afraid to reread Heritage in case it isn’t as good as I remember it being when I was twelve.

I also still remember it very clearly because of the family fight, as my father was fine with my reading at twelve Heritage and Forbidden Tower and The World-Wreckers and even (awful book that it is) Darkover Landfall but the Free Amazons thread? He went to a truly amazing amount of (totally useless) effort to try to keep those books out of my hands. It was a fascinating lesson in where people will draw their arbitrary lines.

the lack of any kind of cultural progress in the Darkover History – just that continual reset referred to is very reminiscent of the SCA idea – an idealization of a midieval myth/fairy story, with all sorts of insistence on “authenticity” that depicts a completely static world.

On the Compact being incredibly implausible, there is a real world event that is similar to the Compact.

Japan managed to completely ‘outlaw’ guns after they ‘threw out’ the European foreigners.