I first discovered Tove Jansson’s fifth Moomin book, Moominsummer Madness, while rooting through my stepbrother’s bookshelf shortly before my 9th birthday. The story of floating theatres, Midsummer magic, and a sad girl named Misabel who becomes a great actress was a favorite summer read for several years after. But it would take me two decades, a trip out of the closet, and a discovery about the book’s author to fully understand why.

The fact that Jansson was a lesbian is not very well known, thanks perhaps in part to earlier biographic blurbs that identified her as living alone on Klovharu Island. In actuality, she summered there with her partner Tuulikki Pietilä, a graphic artist who collaborated with Jansson on a number of projects, including a book about Klovharu, Anteckningar från en ö (Pictures from an Island), in 1996. Some have even speculated that Jansson based the boisterous, friendly (and quite delightfully dykey) Moomin character Too-ticky on Pietilä.

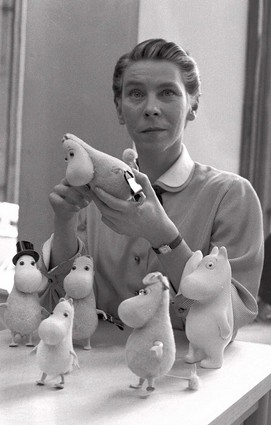

As a prolific artist, sculptor, illustrator and writer, Jansson also lived a bohemian lifestyle similar to the one in which she grew up as the child of two artist parents. Unsurprisingly, Moominvalley is awash in the concerns of such a life, from a reverence for nature to a respect for relaxation and the act of making art.

Likewise, I would argue that Jansson’s Moomin books were shaped by her sexuality. Although there are no openly queer Hemulens, Fillyjonks, Mimbles, or Moomins living in Moominvalley, neither is there a social structure which mandates heterosexual behavior, and in which the roots of queer oppression can always be found. Moomintroll is in love with Snork Maiden and Moominpapa with Moominmama not because it’s the expected thing to do, but because each truly admires his or her beloved. This kind of romantic relationship, free of gender roles and their toxic expectations, is something that queer couples of all orientations and gender identities have long upheld as a good thing for people and for their societies. And Moominvalley reaps bumper crops of these good results. No one hassles characters like Fillyjonk or Gaffsie for being unmarried; Moomintroll doesn’t feel any need to do violent or abusive things to prove his masculinity; and if Snork Maiden likes jewelry or Moominmama enjoys cooking, they do so because these things truly interest them.

Speaking of Fillyjonk, she is also the star of one of my favorite Moomin stories, “The Fillyjonk Who Believed in Disasters” in Tales from Moominvalley. This tale is notable because it emphasizes another theme that queer people will find familiar: The importance of being true to oneself. Timid little Fillyjonk lives in a house she hates among piles of relatives’ belongings, fearing all the while that something will destroy the life she knows. Yet when a violent storm demolishes her house, Fillyjonk finds the courage to embrace an identity free of her family’s literal baggage.

“If I try to make everything the same as before, then I’ll be the same as before myself. I’ll be afraid once more… I can feel that.” … No genuine Fillyjonk had ever left her old inherited belongings adrift… “Mother would have reminded me about duty,” the Fillyjonk mumbled.

In Moominvalley, everyone from Fillyjonk and Too-ticky to taciturn Snufkin and mischievous Little My is not only part of the Moomin family, but Family, in the truest sense of the queer term. I’m forever glad that Jansson’s books played a part in shaping my own identity as a queer child, and I hope that her Moomins will continue to be family to queer people of all ages.

While there may be no explicitly queer Hemulens, is it just my imagination that has them as cross dressers?

The Hemulen are absolutely cross-dressers.

Another queer point, though: The original Swedish names for Thingumy and Bob, sadly lost in translation, were Tofslan and Vifslan, which in turn is short for Tove and Vivica, Vivica being Tove Jansson’s lover of many years Vivica Bandler, head of the Swedish theatre in Helsinki.

Thingumy and Bob being lovers explains quite a lot of their behaviour and their way of speaking, appending the diminutive “-sla” to everything in a sort of lovers’ banter. The red ruby of course is their secret love which they carry with them. All of this seems to have been lost in a dequeerification of the English translation, or maybe the translator was completely unaware of the subtext here.

The two scared little creatures make a fantastic image of how it must have felt to be homosexual in the forties, when the book was originally published.

I have to admit I’m baffled by this post. I think we want to see the author’s personal life reflected in his/her creations, but it’s not always the case. The lack of a restrictive, patriarchal social structure, I would argue, is more indicative of Scandinavian culture than of Jansson’s sexuality – contrast little My with characters such as Pippi longstocking. And issues like “being true to oneself” is so general as to be applicable to anything. But most of all, I oppose reducing *any* writer to the sum of his/her sexuality. Tove Jansson was gay? well and good. But she was also:

A woman

A Scandinavian

A young person (earlier)

An old person (later)

*all* of these things and many others influenced her writing. Mainly the Moomin books are a reflections of her great spirit, humanity and imagination.

I read a few Moomin books as a kid but was not a huge fan. Not only did I not know that Jansson was a lesbian, I did not know she was a woman.

Michael_GR: Yes, Jansson was female, Scandinavian and both a young and old woman. However, I would argue that the Moomin books would not be what they are if Jansson had been a straight, male U.S. American who died at age 34. They might still have been a work of great spirit, humanity and imagination, but they would have been different books–because they would have been written from a different perspective. Analyzing Jansson’s work through a queer lens and mentioning that her sexuality influenced her work is in no way reducing her genius to her sexuality. It is simply putting a fact out there that a lot of people don’t know, and thereby not allowing this part of her life and her genius to be either forgotten or, as Vanapagan hints in the post above yours, to be erased by homophobia.

As for “being true to yourself” being general and applicable to anything, a lot of GLBTQ people would disagree. For many of us, learning to be true to our sexualities takes a lot of sacrifice and loss that our heterosexual counterparts don’t have to go through. Fillyjonk has to lose her possessions and her family’s approval to find out who she is and what she wants in life. I’m hard pressed to think of a gay or transgender friend, including myself, who hasn’t faced the same.

Vanapagan: What an amazing detail! I hope that it was just a translator missing the subtext and not deliberate erasure. Such a pity we English-speakers who do not know Swedish aren’t privy to it. Thank you so much for sharing that.

TJ’s sexuality was not really a secret. In 1982 she published a novel Fair Play which makes it quite clear.

I’m very late to post on this site, admittedly, but I’ve been a Jansson admirer for many years – ever sicne I was 8, actually.

Not being “queer” myself, I totally missed the LGBT undercurrent that pervades all of Jansson’s Moominvalley books…. and, yes, there is definite undercurrent.

In my view, her masterpiece in this series is Moominpappa At Sea – a novel I first read in 1970 when I was 10. After the lighthearted Moomin adventures, this dark mysterious entry flummoxed me. I have to admit, at the time I didn’t like it anywhere near as much as the others.

I read it again this month: March 2013. Jansson was about my age now when she wrote it in 1966: 52 years old. Through eyes much older I now see Moomintroll’s fascination with the frivolous Sea Horses and his ambivalent relationship with the intense Groke in a completely different light. Any Jungian psychologist will immediately recognise Jansson’s projections of her subconscious conflicts, desires and hopes through the Moomintroll ‘ego’ character.

As a child I adored (most of) Jansson’s Moomin books for the sheer fun and adventure. As an adult I admire all her books – and I respect and admire Jansson immeasurably for the gifted, honest and joyous human being she was.

You can’t forget the delightful love between Snufkin and Moomintroll! Although Moomin is said to love Snorkmaiden, it seems more superficial than his love of Snufkin is. Frank Cotterel-Boyce said of the books; “Her experience of growing up gay is there in Snufkin – who is all the more loved for being different. Like the prodigal son, everyone is so thrilled to see him, no one ever asks him where he has been. It’s there too, in Too-Ticky, Jansson’s portrait of her partner. And above all it’s there in the wonderful story where Moomintroll is transformed into the bug-eyed King of California, and his mother recognises him straight away.”

this is a lovely article!! i just wanted to add the fact that jansson was actually bisexual, rather than lesbian. she dated a few men (as well as other women, i think) as a younger woman- one of which (that i don’t remember the name of) appears as another character in the moomin stories (like Tuulikki and Too-ticky). This fact is often overlooked as she spent the majority of her later life with Tuulikki, but i think it’s important to acknowledge!!

to be clear i am also wlw and have absolutely nothing against lesbians; bisexual erasure is just horribly common in the media (e.g. angelina jolie, david bowie, freddy mercury, billie joe armstrong, lady gaga, amy winehouse, kurt cobain, miley cyrus, lindsay lohan, drew barrymore, mel b, ezra miller, anthony perkins, megan fox, aubrey plaza, marilyn monroe, james dean, virginia woolf, oscar wilde, frida khalo, alexander the great, julius caesar, hercules/heracles, etc. just to name a few off the top of my head) and wanted to clear up the facts a little.