I wanted to fall in love with this book. Halfway through, I almost did fall in love with this book.

And then I read the rest of it.

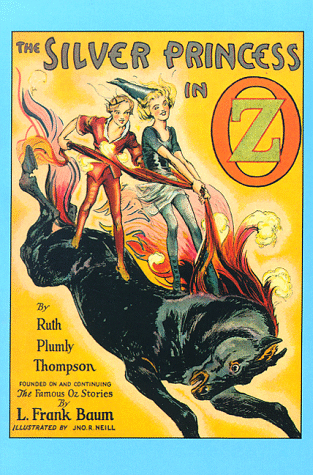

The Silver Princess in Oz brings back some familiar characters—Randy, now king of Regalia, and Kabumpo, the Elegant Elephant. Both are experiencing just a mild touch of cabin fever. Okay, perhaps more than a mild touch—Randy is about to go berserk from various court rituals and duties. The two decide to sneak out of the country to do a bit of traveling, forgetting just how uncomfortable this can be in Oz. Indeed, one of their first encounters, with people that really know how to take sleep and food seriously, almost buries them alive, although they are almost polite about it. Almost:

“No, no, certainly not. I don’t know when I’ve spent a more delightful evening,” Kabumpo said. “Being stuck full of arrows and then buried alive is such splendid entertainment.”

A convenient, if painful, storm takes them out of Oz and into the countries of Ix and Ev, where they meet up with Planetty and her silent, smoky, horse. Both of them, as they explain, are from Anuther Planet. (You may all take a moment to groan at the pun.)

The meeting with the metallic but lovely Planetty shows that Ruth Plumly Thompson probably could have done quite well with writing science fiction. Following L. Frank Baum’s example, she had introduced certain science fiction elements in her Oz books before, but she goes considerably further here, creating an entirely new and alien world. Anuther Planet, sketched in a few brief sentences, has a truly alien culture: its people are birthed full grown from springs of molten Vanadium, and, as Planetty explains, they have no parents, no families, no houses and no castles. In a further nice touch, Planetty’s culture uses very different words and concepts, so although she (somewhat inexplicably) speaks Ozish (i.e., English) it takes Randy and Kabumpo some time to understand her. And it takes Planetty some time to understand them and the world she has fallen into, although she finds it fascinating.

Despite voicing some more than dubious thoughts about marriage earlier in the book, Randy falls in love with Planetty almost instantly. But Planetty turns out to be Thompson’s one romantic heroine in no need of protection. Planetty is even more self-sufficient than Mandy had been, and considerably more effective in a fight than Randy or Kabumpo (or, frankly, now that I think about it, the vast majority of Oz characters), able to stand on the back of a running, flaming horse while turning her enemies into statues. (She’s also, in an odd touch, called a born housewife, even though she’s never actually seen a house before, and I have no idea when she had the time to pick up that skill, but whatever.) Perhaps writing about Handy Mandy in her previous book had inspired Thompson to write more self-reliant characters. Planetty’s warrior abilities and self-reliance only increase Randy’s love, and the result is one of the best, most realistic, yet sweetest romances in the Oz books.

All of it completely ruined by a gratuitous and, even for that era, inexcusably racist scene where the silvery white Planetty, mounted on her dark and flaming horse, mows down a group of screaming, terrified black slaves brandishing her silver staff. She merrily explains that doing this is no problem, since this is how bad beasts are treated in her home planet, so she is accustomed to this. (Her metaphor, not mine.) By the time she is finished, Planetty has transformed sixty slaves into unmoving metal statues. The rest of the slaves flee, crying in terror. Kabumpo makes a quiet vow to never offend Planetty, ever.

Making the scene all the more appalling: the plot does not require these characters to be either black or slaves in the first place. True, keeping slaves might make the villain, Gludwig, seem more evil, but since Jinnicky, depicted as a good guy, also keeps black slaves, I don’t think Thompson intended the implication that slaveholders are evil. The transformed characters could easily be called “soldiers,” and be of any race whatsoever—literally of any race whatsoever, given that they are in the land of Ev, which is filled with non-human people. I’m not sure that the scene would be much better with that change, but it would at least be less racist.

But I don’t think the racism is particularly accidental here. As we learn, this is a slave revolt, with a black leader, one firmly quelled by white leaders. (Not helping: the black leader, Gludwig, wears a red wig.) After the revolt, the white leaders do respond to some of the labor issues that sparked the revolt by arranging for short hours, high wages and a little house and a garden for the untransformed slaves; the narrative claims that, with this, the white leaders provide better working conditions. But it is equally telling that the supposedly kindly (and white) Jinnicky faced any kind of revolt in the first place. (The narrative suggests, rather repellently, that Gludwig easily tricked the slaves, with the suggestion that the slaves are just too unintelligent to see through him.) Even worse, Jinnicky—a supposed good guy—decides to leave the rebel slaves transformed by Planetty as statues, using them as a warning to rest of his workers about the fate that awaits any rebels. That decision takes all of one sentence; Jinnicky’s next task, bringing Planetty back to life (she has had difficulties surviving away from the Vanadium springs of her planet), takes a few pages to accomplish and explain.

It is, by far, the worst example of racism in the Oz books; it may even rank among the worst example of racism in children’s books, period, even following an era of not particularly politically correct 19th and early 20th century children’s literature. (While I’m at it, let me warn you all away from the sequels in the Five Little Peppers series, which have fallen out of print for good reason.) The casual decision—and it is casual, making it worse—to leave the black slaves as statues would be disturbing even without the racial implications. As the text also clarifies, the slaves were only following orders, and, again, let me emphasize, they were slaves. With the racial implications added, the scenes are chilling, reminiscent of the Klu Klux Klan.

(Fair warning: the illustrations here, showing the slaves with racially exaggerated facial features, really do not help. These are the only illustrations by John Neill I actively disliked. If you do choose to read this book, and I have warned you, and you continue on to the end instead of stopping in the middle, you may be better off with an unillustrated version.)

Even aside from this, Silver Princess is a surprisingly cruel book for Thompson, filled with various scenes of unnecessary nastiness: the aforementioned arrows, a group of box-obsessed people attacking the heroes, a fisherman attacking a cat, and so on. (And we probably shouldn’t talk about what I think about Ozma allowing Planetty to walk around Oz with a staff that can turn anyone into a statue, except to say, Ozma, having one set of rules for your friends and another set of rules for everyone else is called favoritism, and it’s usually not associated with an effective management style).

But in the end, what lingers in the memory are the scenes of white leaders crushing a black slave revolt, leaving the slaves as statues, all in one of the otherwise most lighthearted, wittiest books that Thompson ever wrote.

This matters, because so many later fantasy writers (think Gene Wolfe and Stephen Donaldson, for a start) grew up reading and being influenced by the Oz series, and not just the Baum books. It matters, because even in the 1980s, as the fantasy market expanded, it could be difficult to find children’s fantasy books outside of the Oz series (things have radically improved now; thank you Tolkien and Rowling and many others.) It matters, because children and grownups hooked on the very good Baum books and some of the Thompson books may, like me, want and need to read further.

It matters, because I like to think that the Oz books, especially those written by Baum (and the McGraws), with their messages of tolerance and acceptance and friendship despite superficial appearances, had a significant, positive effect on me while I was growing up. They gave me hope that I, a geeky, socially inept kid, who never quite fit into Italy and never quite fit into the United States, would someday find a place, like Oz, where I could be accepted for exactly who I was. To realize that someone else could spend even more time in Oz, spend so much time writing about Oz, and even write a couple of definitely good books about Oz, know it well enough to complain that MGM was messing up its forthcoming movie by getting Dorothy’s hair color wrong, and yet still be able to write something like this, missing much of Baum’s entire point, is painful.

I just wish Thompson could have embraced Oz enough to lose her prejudices along the way. Then again, this is the same author who disdained to even mention the presence of the gentle, merry Shaggy Man, and also almost entirely ignored those retired workers Cap’n Bill, Uncle Henry and Aunt Em to chatter about princes and princesses instead. Perhaps I should be less surprised.

Mari Ness is, among other things, a Third Culture kid, although, before you ask, she’s forgotten all her Italian. She lives in central Florida.

Wow. I… never noticed that aspect of the book. This was one of my favorites as a kid.

Man, these rereads have been kind of depressing (eye-opening, though). Racism, sexism, horrible leadership, the upper class Ozma-friend leeches, various bits of propaganda.

Hopefully reading all this stuff as a kid didn’t ruin me for life!

Huh. I remember reading some of the Oz books when I was a kid. I don’t think I ever got that into the series, seeing that my library only had a couple of copies. I guess, in some cases, that’s a good thing.

ARRGH.

That is all.

(Except: yes, of course it matters.)

@wsean I never read this one when I was a kid — I’m assuming my libraries suppressed it. (The library in Italy didn’t have U.S. books; my Illinois library suppressed anything that might possibly upset parents, and my Connecticut libraries were small and didn’t carry many Oz books at all.) I was really looking forward to it, because the title just sounded so wonderful (Silver Princesses! Oz!). And I must say that the first half of the book is delightful and fully justifies being one of your favorites. If only.

On the bright side, we are close to moving into the incomprehensible zaniness of the fighting houses of the Neill books. And the last two books of the series (I snuck ahead) are definitely an improvement.

@LMWanak The thing is, so many of the Oz books are marvelous – most of the original 14, the first one by Snow, and the last book in the series – or at least splendid children’s entertainment, including some of the Thompson books and the Cosgrove book. And that, in a way, makes it worse – anyone reading this book would feel amply justified in never continuing, and would miss so much.

This book, however, is not.

@katenepveu Arrgh, indeed. And heartbreaking.

Wow. I’m kinda glad now that I stuck with Encyclopedia Brown and Tintin when I was a wee punk instead of this stuff. Being part Black myself – and with a Black and Cherokee mother who was the sort of woman that insisted I not only have a White Barbie but Hawaiian, Native American, Black, and Asian ones as well, the sort of woman who thought it was more important that I learn about Queen Bess than Amelia Earhart, the sort of woman who told me stories about my ancestors who were slaves and those that died on the Trail of Tears – she never would have tolerated this in her house, much less let me check it out of the library.

@Milo1313 And that’s one of the things that gets me. I’d agree with your mother about this particular book, definitely. (I’m fairly sure that Del Rey Books agreed as well – they reprinted most of the other Thompson books, but did not reprint this one.)

But I hope you won’t judge the entire Oz series based on this one book and one author. The other Oz books are, for the most part, really good books, particularly the books by Baum, Jack Snow, and Eloise and Lauren McGraw, and well worth reading. It worries me that people will read this review and decide to skip all of the Oz books as a result – and that’s one of the reasons I found reading this book so painful.

Oh, I definitely won’t hold this book against the series. That wouldn’t be fair. I will continue to be very annoyed by this book, but I’ll keep open-minded about the series :)

I think people exaggerate the effect books have on kids. What resonates in a story is always what’s around them: If you have moderately enlightened parents or black friends around, racism in a book is just going to seem like something that happened far away, and the reader will come away with the bits like “Strong women are cool.” The reverse is true, too: bigoted jerks can be given the most enlightened books imaginable, and they’ll grow up bigoted jerks. Hmm. The Bible is a fine case in point.

That said, if I owned the Oz franchise, there are definitely parts that would get rewritten, and if I had kids reading these, we would have long talks about those books.

Memories of this one aren’t too clear–not even what age I read it. I do recall being really ticked off at Netty’s deciding to trade her alien physiology for a human one just to survive here instead of, say, going home and returning to visit Randy every so often, or fidning a way for him to live in her world. But then, I wanted to be another Tin Woodman so no one could hurt me, physicallly or otherwise…

Agreed about the rewrites. Bonus question–which Oz book had a place called Stair Way?

@9WillShetterly I have a couple of problems with your position. First, the assumption that all Oz readers are kids: sure, that’s when most people were introduced to the series, and that’s where the books are shelved, but I know quite a few adults who read a couple of Baum books as children and decided to track down the rest of the Oz books later, and a few others that decided to check out a couple of the Oz books after seeing Wicked.

But more seriously, your point seems to assume that white children picking up these books will have black friends. I think that’s becoming more true, but I attended schools with few or no black kids, and I’m only in my 30s. (College was different.) Second, you seem to assume that no black children would be reading these books. I think it very possible that a black kid would, like me, be introduced to Oz through one of the earlier books, the movie, or Wicked, and decide to read on. In which case, this isn’t going to seem like something that happened far away.

Finally, even if kids overlook it (and I’m honestly not sure that all kids would), that doesn’t make it ok. In some ways, it makes it worse, because this book portrays Planetty and Jinnicky’s actions not only as perfectly reasonable, but even laudable, allowing readers to think that this sort of thing is ok, especially since it is happening in a fairyland previously presented as tolerant, openminded and accepting of all. And it most definitely is not.

@Angiportus Yeah, Planetty changing herself that drastically – and becoming less strong, cool, and unique – so that she could stay with Randy is another low point in the book, but by that point I was so irritated and upset that I couldn’t care that much.

I should know the answer to your question, but I’m blanking on it! Auugh!

Angiportus, the book with Stair Ways is The Purple Prince of Oz.

When I was a kid I loved Planetty and I didn’t even remember that Jinnicky had black slaves–except for Ginger. When I last re-read this book–more than 25 years ago now–I decided I never needed to read it again.

JRN’s illustrations of Planetty, however, are some of his best late-Oz work, especially the double-page spread of Randy and Planetty meeting.

Just wanted to let readers know that this book has been reworked and republished as The Silver Princess in Oz: Empty-Grave Retrofit Edition.

The republishing was done to ensure this book did not get lost in history as the old copies dried up and the price skyrocketed further.

The reworking corrects and updates the prejudicial race aspects of the book that were clearly unnecessary and distracting. The justification for those minor rewrites also spawned a brand new illustrated short story addition to the book.

It’s out in print and ebook formats pretty much everywhere online.

Hi Adam —

Interesting. So you changed both the illustrations and the text of the final confrontation of the book?

I’m curious — I know minor edits in some editions of The Patchwork Girl of Oz and Rinkitink in Oz were done to remove some racist language of Baum’s, but in both those cases those would have no affect on the plot whatsoever. The changes to Silver Princess would seem more substantial?

Hi MariCats,

Thanks for the reply. A more lengthy one is over in the DorothyAndOzma.com forums.

The edits I did were to the text only. Most of them involved simply removing the word “black.” For some reason Thompson added that word to just about everything in the Jinnicky chapters. The major edit I did was when Randy explained to Planetty about Jinnicky needing all the black slaves to tend to his castle. My rewriting of that portion changes the slaves from human “blacks” to something much more inline with the Oz series. I felt this rewrite put Neill’s drawings in a completely new context and that new readers would be much less likely to make a race connection after reading the new text.

My next two Oz releases contain no content edits aside from the repair of two images that fell victim to some printing defect affecting, to my knowledge, every copy of The Shaggy Man of Oz.

Thanks again for taking the time to write about the racial issues that I’m sure contributed to the original book’s rarity. I know I paid $130 for my copy and that one got cut up–the price of immortality. ;)

@Adam Nicolai — Thanks so much for clarifying this for me; I’ve alerted readers on my personal blog as well.

I have to admit: I was also very unhappy with Neill’s stereotypical images of Jinnicky’s black slaves, and I’m not sure that removing the text references will help there — those are images often found in racist literature, especially in the South. At the same time I can understand that it would be difficult to switch illustrators mid text, and some of Neill’s earlier work is lovely.

As far as the rarity of the original book is concerned, I think this stems from many factors:

1) Oz sales were in decline when Silver Princess was originally published, thanks to numerous factors unrelated to the book’s content: the ongoing Great Depression, the fact that the later Oz books were not printed with the same quality and care (typesetting problems everywhere, a lack of color prints, and so on), and, according to Thompson, a failure to market the books properly and take advantage of a growing market for kids’ books. So I suspect that the book had a smaller print run initially.

2) Del Rey did not respond to my questions about their later reprint decisions, but my guess is that Del Rey declined to reprint Silver Princess partly because of racial issues, and partly because the other Thompson reprints had not sold out well. Since Del Rey eventually moved to print on demand technology for the Thompson reprints they did keep around, I think low sales is the most probable motive.

(Again, though, I haven’t heard directly from anyone at Del Rey, so this is pure speculation on my part.)

3) The Wizard of Oz club did reprint Silver Princess, but I don’t think they had the funds for a large print run.

Again, thanks so much for taking the time to clarify this for me. And on a much happier note, thanks very much for taking the time to bring Shaggy Man back into print — that was definitely one of the harder ones of the Famous Forty to track down.

@MariCats

I was speculating quite a bit on the reason some of the later Oz books are so rare as well. I agree with all of your points. I think one other factor is that The Silver Princess and Shaggy Man books slipped–albeit probably inadvertantly–into public domain. I imagine a big publisher wouldn’t take the risk of doing an actual print run on a book when a smaller publisher could very well release a better quality or less expensive competing product. This is especially true with Print-on-Demand because the only thing a micro-publisher like myself risks is the setup costs and the gobs of time personally invested.

A big publisher making a business decision can’t even hope to compete with a micro-publisher that doesn’t care about whether a book ultimately makes money and is primarily working from a place of love and for a sense of fulfilment and the feeling that they are making a difference.

I’m not criticizing big publishers. They are businesses and probably wouldn’t last very long if they made anything but business decisions. I’m just really glad I don’t work for one of them. ;)

@Adam Nicolai – I’m not sure how much the public domain issue had to do with it; Del Rey did reprint other books by Thompson that entered the public domain, and they declined to reprint Merry-Go-Round in Oz, one of the best of the Famous Forty books, which is still under copyright since one of its authors is still alive.

Marketing might have had something to do with it: when Del Rey originally reprinted the first 14 Baum books those were very easy to find — they were in the little Waldenbooks at the mall, not exactly a mecca for rare book hunters. But I don’t recall seeing any of the Del Rey reprints of the Thompson books at the mall – I found them in a speciality children’s bookstore, and certainly if you were hunting them down you could probably find them, but in those pre-internet days that wasn’t easy and they weren’t as easily available if you were 13 and looking wistfully at the shelves in the hopes that another Oz book would pop up there. I don’t know if this is because Del Rey just assumed the books would sell themselves, or if their marketers couldn’t convince Waldenbooks to stock the Thompson books next to the Baum books, or what.

In terms of Shaggy Man I think something else might have been going on: I was told by librarians that Jack Snow was “inappropriate” for children. It’s possible that this was a reference to his Weird Tales writings, but I think it was more probably a reference to his sexuality, since Snow was gay, and by the 1980s this was pretty openly known.

hello, I was re-reading this blog and I came across the additional comments about “Silver Princess.” You don’t mention that Books of Wonder printed trade paperback editions of the four Thompson titles that Del Rey chose not to publish (as well as at least three hardback versions of her titles that I have seen- “Royal Book” “Kabumpo” and “Wishing Horse” complete with color plates) Upon reading “Silver Princess” for the first time, as an adult in the early 2,ooo’s, I was horrified at the stereotypically exaggerated African American features in the illustrations. (I think there are equally horrible illustrations of Ginger in the earlier titles featuring Jinnicky) At the time, I donated a complete set of the Thompson titles to my local library, but I think I will replace the Books of Wonder copy of “Silver Princess” with the more sensitive “Empty Grave Retrofit Edition” (I am interested in seeing how the new text reconciles with the offensive illustrations.) By the way, Mari, your conjecture that there were relatively few copies of the Oz books selling by the mid to late thirties seems to be correct, as the afterword in the hardcopy Books of Wonder edition of “Wishing Horse” states that it sold approximately six thousand copies. This can be contrasted with Thompson being quoted in the “Baum Bugle” as stating that her first volume (Royal Book) selling “as much in it’s first year as any Baum title. ” I believe the best selling Baum title in it’s first year was “Magic” which I have read sold 28,500 copies. Anyways, I am very pleased to be able to replace “Silver Princess” with a more sensitive version in my local library. On a different note, the Neil illustrations of Asian characters in “Royal Book” are equally, if not more, offensive. In this case, the text is not really the problem. Maybe someone out there in micropublishing land will take it upon themselves to create a version with altered illustrations (it would only be a matter of altering the exaggerated eyes) Lastly, the minor “Topsy” interlude in “Handy Mandy” (which Del Rey also did not publish) contains veiled racist humor seemed to be aimed mostly at adult readers which could use some cleaning up. Actually, the way that Gypsies are portrayed in “Ojo” is pretty bad, too. Sigh. I absolutely adore Ruth Plumly Thompson, and have been trying to do some research on her life for a proposed biography, but it will take a lot of effort to examine and put into context these racist episodes. If anybody out there has any information about Thompson’s life that is not generally known or is in contact with her relatives I would love it if they would get in touch with me at (Email address) handyrandy321@yahoo.com. much thanks!!

@HandyRandy — Thanks for the helpful information about Thompson’s sales. Somewhat off topic, I wonder if that also helps explain why the text for Wonder City is such a mess — the publishers knew that they had to get out an Oz book, especially since the movie had come out relatively recently, but also knew it wouldn’t sell that well so why bother doing decent editing?

In terms of Thompson’s racism — I mentioned the racism problems in my Ojo and Royal Book posts. I’ll disagree with you slightly and say that the text of Royal Book also has some issues, although nothing as bad as Silver Princess.

With the context: I don’t know a lot about Thompson’s background. But from her fiction it seems fairly clear that she immersed herself in stories of the European aristocracy and in more recent novels that celebrated the American South. I don’t know how much you may know about “Lost Cause” literature, but in the late 19th and early 20th century several novels were printed that focused on the honorable nature of the pre-war American South and the tragedy of later Reconstruction, presenting slavery as a positive thing. The myth was helped by the reality that Sherman’s march through Georgia was destructive, and by the fact that black voices were not exactly encouraged in this period; the best known and best selling anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was written by a white woman.

(Incidentally, Gone With the Wind the novel was working against this trope, and even features one nuanced black/Native American character (not Mammy) along with several incredibly racist portrayals. Gone With the Wind the movie was working with this trope, and absolutely embraced the noble/aristocratic/Lost Cause ideal, eliminating the more nuanced portrayals of everyone except Mammy.)

You can see the influence of these books in Grampa of Oz, which doesn’t contain any racist material, but otherwise absolutely echoes a Thomas Nelson Page novel. You can also see it pop up in a couple of L’Engle novels.

Thompson, who was born in 1891, may also have known some old or very old Civil War veterans — my great-grandmother did — which may have colored her depictions. I don’t have any information on this.

Thompson also lived and wrote during the 1920s, a period when the British and American aristocracies enjoyed high levels of privilege and power, but also were well aware, thanks to World War I, of just how fragile that privilege and power could be.

….and I’ve gone way off topic, but my point is, Thompson had read and loved these novels, and other novels about aristocrats : it’s all over her books. I suspect she must have not so secretly longed for that life, especially since instead of being “properly” supported and cherished, she was the financial support of a mother and sister. I give her a lot of credit for breaking barriers and taking on that role, but I can understand if she had wistful thoughts about other possibilities, and worked those into her fiction.

@mari

I remember well that jolt of adrenaline as I walked up to the shelves in a used book store or a B. Dalton and saw the tell-tale tallness of the later Oz books. Ah yet another experience the internet has made moot. ;)

It’s unfortunate that Snow got blacklisted. I enjoyed the darker side of Oz in the Magical Mimics. Frank Kramer’s drawings in those two books are some of my favorites as well.

I’m reading Baum’s Oz books to my daughter. One of the things I liked about them is that they didn’t have awful racist parts like many children’s books from that era. We’re nearing the end of his books (we’ll finish The Tin Woodman of Oz tonight), and I haven’t had to edit the books on the fly while reading them. I read the Doctor Dolittle books to her, and I had to do considerable rephrasing.

We may continue reading other author’s Oz books after we finish with Baum’s, but I’m not sure yet if this book will be one of them. I’ll have to see how bad it is, whether I can rephrase it or skip over the section.

But I don’t think that a book going into the public domain could keep it from being published, bookstores are full of public domain books. I think that people tend to see Baum’s original books as being of a higher order of quality than those that came after.

@Robert L — I think one problem with this book may also be the illustrations, which as Adam Nicolai is noting, were not changed for this edition. He may be right and eliminating the word “black” is enough to change the context of the illustrations, but I really didn’t like the last few illustrations, to put it mildly.

As much as I love the Oz series, I might have to advise skipping this book. I do, however, think that some of the post-Baum books are as good as at least some of the later Baum books – but of course, opinions will differ!

@@@@@AlexBrown — With regard to Tintin: as a child, you probably didn’t read Herge’s early work, Tintin in the Congo. And the later editions edited out the antisemitic aspects of his work that first appeared in a colaborationist newspaper during the Nazi occupation of Belgium.

Herge clearly underwent a change of heart (and also got out from under the thumb of his dictatorial editor) in The Blue Lotus. Although the Japanese in this story are shown in a traditionally caricatured way, the Chinese are not; they are far more authentic than other Chinese characters of the period, partly because Herge had a Chinese informant who became a personal friend.

Of course I am reading through these comments over ten years later but I wanted to point out that I found at least two Del Rey Thompson books as a teen in the late 80s in my local Walden books store.. .Lost King and Gnome King. I can’t recall if there were others and if I just picked these two to ask my mother to buy for me. Either way this was like Christmas morning to find two Oz books that I had never read and was my first taste of the Thompson books until literally last year when I began collecting and reading through them in my 40’s. Of note, Mari, my task has been to read each book in order and then come back to your posts to read your analysis. I am enjoying ths process thoroughly and can’t get enough of your posts.