In terms of contentious relationships with fans, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was the original instigator. Not only was he unconcerned with what his readers wanted, he also was inconsistent with the continuity of his own characters. The chronology of when Holmes and Watson lived together is muddled and Watson’s war injury moves from his leg to his arm seemingly willy-nilly.

But Doyle didn’t receive any serious backlash from his readers until he killed off the famous detective in “The Final Problem.” Fans wore black armbands in mourning and wrote anger letters. Doyle even received some death threats. And to think, they didn’t even have blogs back then.

From the books of George R.R. Martin to the films of George Lucas, fans have a tendency to take ownership of the fictional worlds created by others and to hold those creators accountable when things don’t work out they way they want. But where does this sense of entitlement come from? Do we have the right?

Last month, Laura Miller of The New Yorker, in writing about George R.R. Martin noted “The same blogging culture that allows a fantasy writer like Neil Gaiman to foster a sense of intimacy with his readers can also expose an author to relentless scrutiny when they become discontented.” The article primarily dealt with the impending completion of the next book in the Song of Ice & Fire series and the issues surrounding Martin’s demanding fans, which Miller characterizes “…as customers, not devotees and they expect prompt, consistent service.” Speculation about the future of our favorite fantastical world has always been a part of science fiction and fantasy culture. But it appears we are now demanding quotas of not only timeliness, but also prerequisite on a certain kind of product.

In 2009, I attended a screening of the final episode of Battlestar Galactica at a bar in New York City. There, I found a pretty serious gathering of fans who all sat in hushed silence as the episode aired and over its two hours brought to a close the critically acclaimed story of humans fleeing from the Cylon tyranny. Overall, there were whoops and cheers in the audience, and I left a little buzzed from the beers but mostly happy from the sense of euphoria I got from the finale. The only thought in my mind on the way home was “that was soooo good.” But when I turned to the blogosphere the next morning, it was clear that the consensus was that the BSG finale was in Internet speak an “EPIC FAIL.”

Now, it is very clear to me that seeing a TV show or movie in a room with a bunch of excited fans can lead to a false sense appreciation, and that critical distance sometimes takes days to set in. (Indeed, an article on Slate recently pointed out that the first stage of Star Wars fan grief is denial.) And though I eventually had my own problems with the BSG finale, I never fully identified with some of the vehemence of various Internet commenters, or fans I’ve met in “real life.” Hearing the phrase “fuck Ronald D. Moore” was not uncommon in the weeks after the BSG finale, and we’ve been hearing the same things about the creative team of LOST in recent months. (The feud between George R.R. Martin and Damon Lindelof is layered with irony as both are in essentially in the same boat in terms of fan scrutiny.) In any case, saying, “fuck Ronald D. Moore” or having a similar reaction to dissatisfaction after the BSG finale seems a little extreme. After all, I haven’t written a Peabody Award-winning television program. Nor were fans responsible for creating the show in the first place. Why do we turn so quickly and bite the proverbial hand that feeds us?

The obvious, and most possibly correct answer here is George Lucas. In the world of media criticism, condemnation of the Star Wars prequels is almost completely universal. Not only are most reviews and articles about these movies negative; mocking them also quickly became its own art form. From Simon Pegg’s character on Spaced being fired for refusing to peddle Jar-Jar Binks products, to Patton Oswalt’s stand-up bit “At Midnight I Will Kill George Lucas With a Shovel,” going after George Lucas on a personal level is fairly uncontroversial. The creators of South Park depicted Lucas literally raping Indiana Jones after the release of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull; an image most certainly derived from the fan battle cry, “George Lucas raped my childhood!”

As I’ve written previously, I don’t actually think George Lucas did anything to my childhood, but that the critical attacks levied at the prequels and the subsequent Clone Wars cartoon, (when stripped of their hyperbolic and ad-hominem vehemence) are at the very least understandable. In short: the original Star Wars films were about relatable people fighting the establishment, and the new Star Wars films are about people we barely understand being manipulated to fight each other. If one liked the first set of movies, it’s easy to see why that same person would dislike the second set. However, other than delivering something that didn’t look like Star Wars, what did Lucas do to deserve the massive backlash that followed? First, he created Star Wars in the first place, which just like the dislike for its prequels, is fairly universally loved. Am I saying Lucas is a victim of his own success? Yes, partially. But it’s deeper than that.

The Lucas marketing machine rammed Star Wars down our throats from 1999 to 2005, and at first, much of the fan community accepted it, because we loved Star Wars! But, because it had permeated so much of the culture climate, only to be disappointing, the backlash almost equaled the promotional efforts. Basically, every time we saw a Jar-Jar doll after The Phantom Menace, many of us became angrier with each toy sighting.

But what of BSG or even Doctor Who? Are these things being overly promoted in the same way Star Wars was? Certainly not in actuality, but in our minds, we might be hyping up these things because we feel like we need to. The Star Wars prequels got us hooked on hype like a drug. And even though we came down hard from that hype, we still want to feel that euphoria of anticipation again. The people marketing genre films and television know this, and so we get set visits from The Hobbit before they even start filming, or casting news about movies that don’t even have directors. All of this build-up ultimately lays the foundation for backlash, in the same way all those Phantom Menace Pepsi cans did back in 1999.

And the hostile defensiveness from the creators of various genre properties directed at the fans seems to be growing. As The New Yorker piece points out, George R.R. Martin has a rocky relationship with his fans. Doctor Who showrunner Steven Moffat recently complained about fans who spoil the plotlines of episodes. This comment, along with others from Moffat, seems to indicate he feels a kind of affront towards fans who have certain expectations (demands?) of the show’s plotlines. Early on in his tenure as Doctor Who showrunner Moffat claimed that a show about “time travel can’t have continuity problems.” And in certain quarters, I’m sure this was interpreted as blasphemy. Even in the Tor.com office, we’ve had heated arguments on just what is or is not implied on Who.

What creates this sort backlash or animosity between fans and creators? To me, certain fans like to speculate on the things they don’t see in a book or a show or a movie, and the creators don’t care about that at all. For the creators, there is no “expanded universe.” What you see is what you get. They worked hard on it, isn’t it enough? On a DVD extra for the British version of The Office, Ricky Gervais summed it up best. After several of the actors speculated on what their characters did after the last episode Gervais pithily responded, “I’ll tell you what they did. Nothing. Because the show ended.” So perhaps Lucas has a right to tell us Anakin created C-3PO, Russell T. Davies can change the number of times a Time Lord can regenerate, or George R.R. Martin can switch a gender of a horse in-between books.

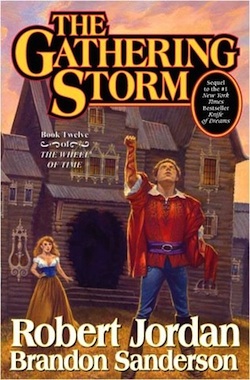

In marked contrast to this phenomenon, Brandon Sanderson’s take over of the Wheel of Time series from the late Robert Jordan received little to no considerable backlash. This could have been due in part to Sanderson’s credibility with fans of the fantasy genre, coupled with his ability to communicate with his fans effectively. In short, readers were reassured beforehand and that reassurance was rewarded by transparency during the process and the timely delivery of a satisfying volume of story. In this instance, engaging with fans throughout the process resulted in a smooth transition.

In marked contrast to this phenomenon, Brandon Sanderson’s take over of the Wheel of Time series from the late Robert Jordan received little to no considerable backlash. This could have been due in part to Sanderson’s credibility with fans of the fantasy genre, coupled with his ability to communicate with his fans effectively. In short, readers were reassured beforehand and that reassurance was rewarded by transparency during the process and the timely delivery of a satisfying volume of story. In this instance, engaging with fans throughout the process resulted in a smooth transition.

With such access now available to fans, is it now necessary for showrunners and authors to change from an “If we engage fans…” mentality to one that asks how? For larger authors like Martin or Gaiman, as their popularity nullifies professional critics, this becomes a hefty question indeed. In speaking with his tendency to communicate directly with the fans Neil Gaiman told The New Yorker last year, “I have at this point a critic-proof career. The fans already know about the book.”

Does it then become a question of levels of engagement with fans? What would it take for guys like Gaiman and Sanderson to suddenly have problems of George Lucas proportions, where both the critics AND the fans are calling for blood? What would they have to do?

It’s possible the biggest crime of all would be no communication at all. Can we even conceive of movie or a novel being made in an established universe by an established author completely in secret? What would happen if Steven Moffat refused to give a single interview for the next season of Doctor Who?

I only know one thing for sure. If by the end of this season of Doctor Who, Steven Moffat pulls a Conan Doyle and kills the Doctor for all of time, this blogger will be doing a hell of a lot more than just wearing a black armband to work.

My investment in the show, the character, and the story feels far too personal to let someone else destroy it. And that’s really the heart of the question here. How useful is such an emotional investment, ultimately? Is this something that needs to be dialed back? Or is it a sign of the changing ways in which we enjoy our favorite shows and books?

Ryan Britt is a staff writer for Tor.com.

Fundamentally it’s the logic of the stalker:

“I love you, therefore you must love me”.

Well written. One comment: Sanderson receiving no backlash probably had to do with the joy we all felt that WoT would in fact be completed.

@edgewalker. Fair point!

@Ian_Coleman: Creepy! Never thought of that way. :-)

I think it is almost a double edged sword here. The author/creator works on bringing something to life and getting it out to the public. They toil and sweat and hope it will be loved. Then when it is loved/acclaimed suddenly there is this sense of “I have to do that again??” So while we clamor for GRRM or Rothfuss or any of the other ones, they are worried about sophomore slump, comparisons, stress etc. Congratulations, you are successful! Now get back to work!

Didn’t Gaiman write something along the lines of “GRRM is not your bitch” or something like that? I seem to remember a blog entry referring to something like that.

And yes, if they kill off the Doctor, there will be much gnashing of teeth, rending of garments, weeping and wailing.

Fans take these creative efforts to heart because it becomes part of their identity and worldview. The creative works speaks for them and to them. Fans gain a community and sense of belonging with others who share this new slice of worldview.

Then comes hyper-marketing, wherein creepy marketeers manipulate your love of a creative work to extract ever more money from your wallet. Fan start to feel like chumps, emotionally manipulated by creeps for a dollar. Backlash for sure. Hi, George Lucas!

Then comes betrayal of the storyline, where the ideas in the work seem to be betrayed in the final ending. I mean YOU BSG and LOST.

GRRM received so much backlash because he promised short delivery and didn’t deliver. He didn’t deliver because he wanted to make the story right and wasn’t satisfied. He could have shit out a crappily time-lined and weak conclusion and fans would’ve bought it. He stayed true to himself and his work. Hyper-marketing tolerance rises with the quality of the work.

Any GRRM backlash is temporary, as long as he delivers works that stay true to what drove fans to consume everything he has ever done.

Iain_Coleman @@@@@ 1: So true!

Edgewalker @@@@@ 2: That combined with a fair amount of backlash against the WoT series in general as it continued to get longer and more complex. I think that a lot of the people who might have caused a considerable amount of backlash against Sanderson had already done their griping years before and left to pursue other bloodletting.

As far as it goes, I think the consumer has a right to bitch all they want about how much they don’t like a finished product once it’s released and paid for. I don’t believe said consumer has any right to bitch about how long it takes an author or film producer/ director/ whatever to release another chapter in the series.

People are always talking about GRRM “owing” them the next book to the series because they’d paid money and time to the previous books. Well, sorry, but no. Neil Gaiman was absolutely correct in his “Not Your Bitch” article, whether it’s in regards to a long series like WoT or ASoIaF or the films like Star Wars, or a TV series like Doctor Who. It takes a lot of blood, sweat and tears to produce such creative vehicles and no fan is owed anything from those creators.

There’s definitely a growing sense of false entitlement amongst the fanworld alongside a rapidly decreasing degree of patience. Personally this had made it more difficult to deal with other fans of a series simply because I find their behavior childish and offensive.

“But Doyle didn’t receive any serious backlash from his readers until he killed off the famous detective in ‘The Final Problem.'”

Man, you couldn’t have added a spoiler warning?

I’m kidding.

A few thoughts…

What you say about communication with fans is, I think, very true. I think that part of Gaiman’s popularity as a writer is that people enjoy him as a person. I’ve been told by a bunch of people who have met him that he’s enganging and charming. The personality and accessability are important to fans. Same goes for John Scalzi, whose web presence is significant and Brandon Sanderson, whose web presence is much smaller than Scalzi’s but interaction with fans is still important to him. Plus they are all very damn talented.

Other thought: Moffat’s statement that time travel = get out of continuity free card…I can’t make up my mind on whether or not I agree with him. Regardless, the fact remains that fans expect–time travel or no–if not proper continuity at least internal consistency and reasonable feelings of closure at the end of story arcs. If Moffat provides those (and I think for the most part he has) then I’m ok with him messing around with continuity.

Last thought…you and I have both written posts for tor.com regarding fan and celeb relationships featuring pictures of an angry Simon Pegg.

Interesting piece. I wrote one myself a while back looking at this phenomenon as the downside of authorial community-building, based on a piece by Guy Gavriel Kay. If you make yourself accessible to fans, you’re also making the fans accessible to you.

And the anonymity of the Internet leads people to say things on-line that they would never say to a person’s face.

I think the issue of Martin in this actually different from others. Yes, it’s true that he’s killed a lot of characters, and that frustrates some of the fans. It has me, but I also understand and respect that this is his work, and a story which he is telling, not me. I believe the problem with Martin is one of unmet expectations. Consider the following factors: 1) A Feast for Crows is easily the worst book in his series; 2) he leaves the two most well loved characters out of the book, and it adds to frustration; 3) a large portion of the material in A Dance With Dragons was originally slated to be part of the fourth book; 4) when he decided to make the split between the two books, the expectation (as propagated by Martin) is that the second novel would be out sometime in late 2006 or 2007; 5) we are now nearly 6 years since the publication of the last installment in this series; and 6) he has published other items and worked as an editor on many things in the interim. I believe it is the combination of these factors that drive the problematic relationship Martin has with his fan base, more so than the choices he has made with his characters.

I hate to give into ‘non-specific’ (and slightly obvious) abstractions, but really… the wide range of over-emotionally-involved fiction fans are no different than the people who obsess about sports, politics, religion, popular culture, etc. They do it because co-fixating with others of similar scale (even diametrically opposed) passion creates cameraderie, cliquiness, and a sense of belonging. You don’t typically get this type of behavior where there is no audience to act out in front of (i.e. home alone). It’s mostly mob-mind. Though obsessive collecting is a different matter. I think to analyse it in a non-psychological (or even non-pathological way) is to given in to the hype or that there is some deep meaning in the artist-observer relationship. That being said, very few people befriend or even relate to those who are invulnerable to passions about something. A little bit of madness happily binds us all.

I think you’re relying a bit too much on overgeneralizations and connections that don’t really connect.

For instance, while the New Yorker piece about George R. R. Martin did discuss the subset of his fans who are put out with him, it also went into quite some detail about the extremely warm relationship Martin has cultivated over years with the fans who aren’t running web sites decrying the time it’s taking him to finish Ice and Fire. Which turns out to be, you know, most of them.

Additionally, to the extent that the article actually looked at Martin’s own attitude toward the fans who rag on him, it mostly showed him to be dealing with it philosophically. So to sum it all up as being about “George R. R. Martin’s rocky relationship with his fans” is rather misleading. I have one brother I’m kind of annoyed with at the moment; that doesn’t mean it would be fair to talk about my “rocky relationship with my family,” most of which I get along with just fine.

And neither Martin’s relationship with a small group of cranky fans, nor Steven Moffat’s occasional critical remarks about people who post spoilers immediately after Doctor Who episodes have premiered in the UK, really add up to support for your topic-sentence assertion that “the hostile defensiveness from the creators of various genre properties directed at the fans seems to be growing,” because neither Martin’s nor Moffat’s behavior appears to be notably hostile or defensive. Your blithe assertion that some kind of barely-defined “hostile defensiveness” is “growing” is just that, an assertion which you really don’t back up at all.

I think you’re trying to start an interesting conversation here, but your approach is confused at several points. Another instance: “If by the end of this season of Doctor Who, Steven Moffat pulls a Conan Doyle and kills the Doctor for all of time, this blogger will be doing a hell of a lot more than just wearing a black armband to work.” This is just silly. Obviously nothing of the sort is going to happen, first off for the very simple reason that Steven Moffat doesn’t own Doctor Who the way that Conan Doyle owned Sherlock Holmes. Doctor Who is an ongoing business, and Steven Moffat works for the owners of that business. You’re trying to make a point about our feelings of emotional investment in ongoing stories, and it’s a good point, but the sheer implausibility of your what-if serves to distract us from actually engaging with it.

I’d say fans are owed one simple thing–respect. They aren’t owed a timeline, they aren’t owed a plot line, they aren’t owed a character or a character’s immortality. What they are owed is the respect expressed by a sense of sincere craftsmanship and integrity in the crafting. Granted, there is a blurry line, one as fans we’ll never know the truth of barring some drunk-internetting confession, between a creator turning out something they actually thought was good and a creator turning out a half-assed product they knew was half-assed.

Since Who was mentioned, let’s take a quick look at the recent pirate episode and one simple example (there were more in that episode). When you’ve got people meandering (and I really mean meandering) lazily toward certain death and the best anyone puts up in terms of trying to prevent said certain death is to pluck idly at a sleeve, that isn’t showing respect to your audience (let alone it happening repeatedly). Idiot plots don’t show respect to your audience. Having plots revolve around people not speaking to one another (yes, I’m talking to Lost folks here) doesn’t show respect. Writing the same book a dozen times to continue a series doesn’t show respect. Having events not have repercussions beyond a single episode doesn’t show respect. And so on.

I’m fine with delays, I’m fine with bad books, bad movies, but at least show me some basic respect as a reader/viewer etc.

Some people are whiners, as anyone who has ever worked in retail will tell you.

Some people just don’t know how to do their damn jobs, as anyone who has ever shopped retail will tell you.

I suspect that a lot of the discursive environment of fandom comes from the fact that fans would have little to say to one another without the fan-objects to discuss. It’s like talking shop for nerds. I certainly know a lot of people who bravely sat through this or that movie or TV show because they knew their friends would be talking about the next day. Liking it or not was immaterial; in some ways one gains a little rhetorical advantage from disliking something.

I was going to type up a long thing about Martin, but @10 Jhirrad summed it up really well.

The only thing I would add is that it isn’t just the 6 years it’s been since the last book. It’s the fact that it’s been 11 years since we had a viewpoint from the Wall storyline or the dragon storyline.

I am going to agree with Jhirrad @10 and say that when an author delivers a finished book to his publisher and the publisher says it is too big they will have to split it into two I just expect a book in two volumes. I do not expect that 7 years will pass because what was once presentable by the author’s standards has suddenly become a long project of revisions.

It is a matter of time.

A cliffhanger you have to wait a few months of summer to resolve is mild but bearable.

A cliffhanger you have to wait a year due to publishing cycles is a bit more irritating but people can accept that writing a book takes some “time” (time being relative and bendy in the expectations of different people)

A cliffhanger you have to wait several years to resolve cannot possibly be spectacular enough to counter the expectations placed on how excellent the writing must be to have taken this long.

A cliffhanger you wait several years to resolve and then it is not resolved in the next book is infuriating enough to drive people away from the franchise.

and then there is the fact that in 40 years the collected works will be read within a matter of months and the people of the future will not have to wait so their expectations of conteporary writers will still be the same as the ones we have today. :)

I think the article jumps a bit too much between it’s positions to present a poignant argument. Is it talking about critical reaction, because I wasn’t aware that calling crap crap was entitlement. Expecting speedy delivery of the next installment in a series, a sequel at all or expecting a writer/creator doing a piece of fiction to personal specs, I can get behind that this is entitlement. But criticizing something after it’s finished or mocking something for being bad, that’s not entitlement, that’s just normal.

As for the whole “fuck Ronald D. Moore” at the end of BSG, what reaction do you expect when someone presents cultural suicide as something positive.

This post is kinda poignant considering SyFy has blocked me on twitter because I had the nerve to be upset at the cancelling of SGU a telling them I wouldn’t be watching any new shows on the channel while encouraging others to do the same. Shame on me, I guess. :-P

Fans vs George Lucas

I have had many arguments/discussions with friends over this very subject. The one that causes the most derision is “who owns Star Wars? Lucas or the fans?” Obviously, Lucas owns the physical and intellectual rights to the whole Star Wars Universe. But! He doesn’t own the memories we all shared as kids watching these movies and falling in love with them. These movies helped shape our imagination and our childhoods. So when Lucas tells the fans that love the original uncut trilogy they are wrong and his new “Special Edition” versions are now canon is insulting to fans that have helped build his empire with the money we spent. I know my viewpoint is silly. They are only movies. In the end I could ignore the whole thing is he would only release the original trilogy formatted for HD TV’s.

Doctor Who

I’ve loved Doctor for as long as I have loved Star Wars. I didn’t get to see the new series until about a few years ago and I was all in again. I was sorry to see that Moffat wasn’t always going to be faithful to certain aspects of the continuity of the series. I understand, how can you have continuity issues in a Time Travel show? Well you can at least acknowledge the previous continuity and establish a workaround. Glossing over the regeneration limit was disappointing. Can I live with it? Yes. Would it be too hard to write a story arc that has the Doctor seeking to circumvent this limit? Nope.

Either way, I will continue to watch the show and support it fully because in the end, the show loves the fans as much as we love it. (BTW – I’ll be right there with you if he permanently kills off the Doctor)

Writers

I think you are dead on about Sanderson. He handled the whole situation perfectly and the fan base embraced him for it. Plus it helped that he was able to breathe new life into the end of the series. Unfortunately, George R R Martin was the victim of internet nitwit’s attacking him personally. Heck, I’ve been waiting for David Gerrold to finish the War of the Chtorr series for almost 20 years now. I would never attack these authors’s personally but it has affected how I pick new series to read. I almost never start a series until they are at least halfway through (if more than 3 books) the series.

I think Gaiman and Sanderson would start having problems with their fans if they started treating them like Lucas has been known to treat his.

In the end I think the only thing we as fans can reasonably expect from all of these creators is that they try (if possible) to finish the stories that they begin to tell us. Or, make available the original series that gave you the ability to build your empire.

@13. Billcap – You really summed up what I was trying to say much better.

@@@@@ 11. designguybrown – You are absolutely right. Just listen to your local sports talk radio show on the way home today and you’ll get blown away by people who are complaining because they think they can run the team better. It’s no different then some of us fans at times.

I think that someone like Pat Rothfuss communicates effectively, and therefore sets realistic expectations for himself and his fans, and for the most part this could limit the extreme backlash from readers. In several interviews, he has, from the beginning, told us that writing book 3 will take “exactly as much time as it needs to take”.

Sanderson communicates effectively, also setting realistic expectations as well as the fact that to date, he has pretty much met his deadlines.

I hope that Martin does the same for book 6. Tell us from the beginning that it will be done, when it is done. Failing to meet deadlines after commincating them to a rabid, zero-consequence internet fanbase only encourages lousy behavior.

There is plenty to read out there. When the books are done, we will read them.

Also, the Sanderson books are better than almost all the Jordan ones. (Especially those middle ones where nothing happened.)

@Patrick Nielsen Hayden

You are absolutely right that I don’t mention the warmer relationship between Martin and most of his fans. That was probably an oversight. However, I also don’t mention those fans who are in LOVE with the Star Wars prequels, either. They certainly exist and are probably nice people! So yeah, I omitted some positive relationships for the sake of my argument.

Naturally, I’m being a bit hyperbolic with the Steven Moffat thing and whether or not the Doctor will stay dead. Of course, I agree with you that it won’t actually happen. However, one of the best parts of science fiction and fantasy is that we get to postulate “what if?” even in our non-fiction musings. And in terms of emotional ruminations, I’d say implausibility has nothing to do with emotional weight. After all, I make it a point to imagine at least six impossible (and two implausible) things before my first coffee break every day!

As for my quasi-baseless assertions about backlash brewing, or hostility rising and/or falling, I think the existence of the conversation proves some kind of trend at work here. Whether or not I am right or wrong is not really what is at stake for me here. The point is, I think fan backlash should be discussed in some form. And so here we are. Discussing.

In almost every single one of my articles like these, discourse always wins over any point I’ve made.

:-)

What I am wondering is: what’s the other option?

If we don’t fixate, obsess, and rag about our popular (genre) culture and its creators, what else is there to do? Intellectual discussion, deep artistic criticism, and thoughtful non-judgmental analysis is dead. Or is it hiding? When’s the last time you went to a discussion about (or contributed to) the spiritual-cultural components of deep space travel (you know, like generation ships)? What you say? – this con or that con panel. I see, and how many people were in the room at that ‘talk’? 7? Did it only get interesting when someone brought up something passionately controversial that existed in some scifi universe? Probably.

Ho-hum. I’m not against escapism, popGenreCult, passionate wranglings about tv episodes (hey, i’m all Picard vs. Kirk), but is that all we got? Can we not occasionally rise (not necessarily above) but away from it and not act like rival tribe gangs who duel to the death because their god/priest/author delivered the goods and the other tribe’s did not. I’m not talking Spec Fic Literary Master class at Stanford – just thoughtful, you know – a bit more inspiration, wonder, and awe — and a little less vitriol — because, hey, isn’t that how we got into speculative fiction in the first place? Though, an ‘Anti-Baltar’ BSG tailgate party does sound tempting.

@Del

Fair distinction. Though, I suppose I developed a knee-jerk reaction to

defending the ending of BSG because the fan-hate seemed to snowball so quicklyand out of proportion (in my opinion) with how “bad” it might have been.

Here’s where I’ll roll out what I call “The Gigli

defense” This movie was certainly bad, but during the summer

it was out, the snowball effect of people making sport out of making fun of it was out of control. Certainly there were other bad movies as bad if not worse than Gigli, but Gigli had the Gigli effect of being bad AND high profile.

NowI’m not saying the BSG finale is bad, or Gigli is good, or that J-LO is a cylon. Instead, it occurs to me that certain “hate” gets caught in a

kind of cultural accelerator and is suddenly *perceived* as worse than it is.

If I remember right, there was some concern before Sanderson took over the WOT, and there was a significant amount of criticism after TGS was published. The issue that people seemed to have was a matter of tone – they said felt different.

As far as the long breaks between releases, I think LongtimeFan summed it up in his closing paragraph. I was a late arrival to WOT (I finished cought up just as TGS was released) and ASOFAI (just getting ready to wrap up Game of Thrones). With both series, I don’t have to wait too long to see what will happen next. As a result, I have a hard time relating to the folks that, reasonably, get frustrated when the next installment is delayed.

The trouble that I’m having with this season of Who is the same thing. While RTD didn’t write the most exciting of stories, he managed to bridge the tone of the original series with the commercial needs of modern television. Under Moffatt’s guidance, the series feels more like another Jekyll or Sherlock, and less like Dotor Who.

Of course, the creators are free to make changes that they see fit. Fans may or may not agree with all of the decisions, but if they are true to the tone of the series, they can debate them reasonably (Rand either living or dying is reasonable, the Dark One winning is not). What fans have the right to demand, however, is that the creator hold to the underlying precepts of the show. The Doctor isn’t human. The Starks and Lannisters aren’t going to have tea and dumplings (bad example, I’m pretty sure anything goes in this series). Where Lost and BSG stepped wrong was that the last half season or so felt tacked on – like it they were gearing up for a random ending and needed to try and justify it. That’s why nobody get mad at the end of the Mistborn trilogy – it worked. I just want everything to work.

@jasonhenniger No doubt.

http://www.tor.com/blogs/2011/04/last-night-i-dreamt-that-simon-pegg-hated-me

Sorry about spoiling “The Final Problem”

Then of course there’s the point… how often does the author/ director/ artist’s visions actually make it to the public intact and unmolested? I would say the vast majority of works out there have been ‘modified to meet the needs of distributors and investors’ (i.e. how can we dilute this so that it appeals to the greatest number of paying customers, who most likely will not love it, but will tolerate it long enough not to spread too much negativeness (or worse, indifference) so that their friends will still pay to see it (often called the Disney effect)) – because, hey, when was the last time you saw a non-profit movie studio? These are million-dollar productions. Same with authors, music, and artists – will it sell widely? What’s my return on investment? -and of course, the author: “geez, i really need to pay rent this month. I think that i’ll follow my publisher’s guidance.” Director’s cut? – don’t you believe it. And hey – are customers flocking to independent studios, publishers, and unsigned artists – not to a degree that they can making a living off it – i mean, hey 3 showings at the local indy cinema -only 5 in the city- over a week. Why see something if no one that you know has seen it and therefore have no opportunity to harangue it. I am not hopeful.

I had to laugh at JFKingsmill16@18, because I had completely forgotten about the Chtorr. I reread it several years after I first started it, and realized that it had never been resolved. I eventually got rid of the books I had, and if a sequel is ever written, won’t buy it. I haven’t flamed GRRM, but I am irritated with him. “A Feast of Crows” was a horrific downer, but he promised more of my favorite characters in “A Dance of Dragons”, which was almost complete and would be out soon. Six years later, I am seriously considering whether or not to buy it, or just get if from the library (so what if I’m on a waiting list for a month or two). With previous books, I bought them the day they came out, and also bought copies for my nephew. Authors don’t necessarily “owe” anything to fans, but if they annoy them enough, they can lose customers. I hope that he concludes the series with “A Dance of Dragons”, because it really feels like he has lost interest in the series.

As for Ricky Gervais’s comment, obviously he doesn’t realize that characters live on in fanfiction for obsessed fans. : )

@28 dsolo

Nope, there are 2 more planned after this one. And going from experience, that means that it will be 22 years before the series is done. He’ll take between 5 and 6 years to write each half of the next two books.

Creators, filmmakers, writers, and the like owe audiences and fans one thing and one thing only – respect. They do not owe fans open communications, a line of feedback that may or may not influence the final product, or any other type of attention that invariably feeds the sense of entitlement (I always thought of it as ownership, but entitlement fits too).

The problem here is not some media conspiracy or the creators themselves for failing to be in touch with audiences. You seem to suggest that all of the failings of Star Wars, BSG, Doctor Who, etc. is a failure on the creator/writer’s part to successfully communicate with the fan base (forgive me if I misrepresent your point here). Personally, I think that’s utter bullshit.

Creators have a kind of social contract in place with their audiences. It is based on respect. Sometimes the creator is completely in line with what the audience wants, sometimes the audience is out of step with the creator’s intent, and other times the creator breaks the social contract.

Audiences break the contract by stepping out of line and over-indulging their fandom and sense of entitlement. Yes, the digital age has fundamentally changed the way in which properties are marketed to us, but we still choose to consume this media. We still choose to indulge it and marry it to our expectations. No one forces this. We are not made to be part of a marketing campaign. We are not forced to build up romanticized and idealized fantasies about what you want from said movie, book, or television show.

Drawing from your own piece, your assertion that the Star Wars prequels are terrible lies with your inability to square Lucas’ vision with what you wanted. You break the contract by making your definition of Star Wars to be around your cherished thoughts regarding the original trilogy. Using critics to bolster you beliefs is a straw man argument because Star Wars films are always panned by critics – for example, at the time of its release, the NYT called “Empire” the worst sequel in the history of film, little more than a toy commercial.

(Incidentally, the notion [made popular of late by that guy who likes pizza rolls] that the prequel characters are unknown and inaccessible is ludicrous. Jedi are space monks/cops, Anakin is a spoiled boy that becomes isolated by his sense of love, power and perceived fate, and the Chancellor is evil, a mastermind of chess. It is really simple, guys. So what if the characters did not link directly to character tropes as is the case with the first trilogy?)

But Star Wars is a cultural anomaly, owed, perhaps, to the amount of time it has spent stewing in the collective unconscious of our society. Dr. Who is in a similar position. It has been around longer and is a giant part of British genre culture, and its fans are similarly always up in arms about something. Time, it seems, breeds this sense of entitlement.

But is this entitlement worth being indulged, as you seem to suggest by playing up the importance of the lines of communications between creator and fans? Absolutely not. Talk with the fans, sure. Listen to them and see if their thoughts can provide critical feedback and help shape your work … maybe. But, never ever indulge to the point of pandering. Films and movies are not some kind of crowd sourced entertainment; if they were, then every movie, book, and television show would be “Snakes on a Plane.”

Creators and fans enter the social contract expecting a certain level of respect. Creators expect that you’ll create their vision enough to give a whirl (if you like it great, if not oh well). Sometimes the audience falls out of step with this contract – as is pointed out above – and other times it is the creator that breaks the social contract, and this speaks to your other example, Ronald “Fucker” Moore.

He deserves the ire of fandom because he broke the contract by disrespecting the fans. The second half of Season 4 is lazy, derivative, and completely inconsistent with the previous seasons’ integrity and continuity. As the guy’s own drunken podcasts and egotistical interviews attest, Moore backed himself into a corner with the show: he was rushed to finish the second half of the season, and just said “fuck it.” (Yes, I’m paraphrasing, but the guy does say that he was too busy on preparing Caprica to really get into how to tie the show up

In the end, speaking to the questions at the end of your piece, emotional investment is not at fault here. Emotional investment is good; it is what fan bases are built upon. The “changing ways” may incite and inflame these emotions – for better or worse – but that does not make those ways inherently bad. No, the fault lies with whoever breaks the social contract first. In some cases, as is the case with Star Wars and Dr. Who, it is the fans that shatter the contract out of the weight of their own expectations and misguided sense of entitlement. Whereas, with BSG, the fault lies with Moore because he fumbled, spewed out a trite piece of derivative crap that he then peddled to fans as the be all end all.

This was a great piece, and something we all need to think about. Everyone has had some great thoughts. The only thing I want to say is that when I am upset with something in a show or book series, or musical album, I trust the creators and try to understand their vision. Most of the time, this patience is rewarded with new insight and a deeper understanding of the meaning of the work as a whole, rather than petty rage that my favorite character didn’t get a happy ending. Sometimes things don’t work for me; personally, Lost fell flat in the final season; at the same time, maybe I just don’t get it. Fans think hard before they speak.

Respect is exactly it.

Part of the problem for me with Star Wars is the origin aspect of it all. The origin story is built throughout the series (You knew my Father?).

Different people lock on to different tidbits scattered throughout the movies. Attempts to make the origin story a story by itself totally fell flat. Young Anakin and Young Palpatine feel more like Muppet Babies than Star Wars. Jar Jar further emphasizes the Muppet Babies angle and is therefore the focal point of the hate (IMO).

The rest of the problem involves modding the originals. The fact that Lucas refused to acknowledge that Han Solo was no longer the guy he was by making Guido shoot first is unforgiveable. Trying to burn all other Han Solo’s out of existence (by not making the orignal available) was childish. This I believe was more damaging than Star Wars Babies, but Star Wars Babies felt the wrath because there was nowhere else for it to go.

Also, as far as Wot goes, I don’t think BS got through unscathed. I can not count how many “the writing just isn’t the same” or “Mat is totally off” comments I’ve read. Acknowledging that is what allowed the fans to move on.

All in all, I think if a person acts like Lucas and effectively says “It’s my story and I do what I want,” the fans will revolt. If a person acts like Sanderson and says something like “Yeah I had a really tough time reconciling that aspect of the story, but given all the options I think this is truest to the characters,” the fans will still gripe, but stick with it.

It all goes back to respect.

P.S. I don’t know where she got it, but my mother-in-law found a DVD set that has the original theatrical versions of Star Wars. Maybe Lucas is slowly realizing the error of his ways?

@26

If we go by Scalzi’s statute of limitations on spoilers, you are ok by about 115 years.

Funny thing about “angry simon.” Maybe he’s a natural choice for this topic because he’s a huge geek himself and seems such a pleasant guy..and looks great when pretending to be angry.

As far as Star Wars is concerned, I can say my disappointment isn’t born of some misguided nostalgia. For many fans of Star Wars, the novels of the Expanded Universe had filled the gap the original trilogy left in our lives for years before the prequels were even announced. These novels aged and developed the characters and universe in ways that not only continued, but improved upon the concepts from the original movies. We saw Han and Leia start a family, Luke open a jedi academy, and after two decades, saw the Empire and the New Republic declare a lasting peace.

The real kicker was the New Jedi Order series. As the Prequels were being released, arguably the low point of the film franchise, the novels were hitting a new high with the New Jedi Order. Galactic peril on a scale previously unseen, repeated defeats and frustrations for both heroes and villains alike, and even notable character deaths cast the series in a light that made fans step back and thing that this was something different and new, but still true to our concept of what Star Wars should be. And Jar Jar was what we had to compare it to. How could the prequels not lose?

It was a simply question, really. The answer is no. The audience is owed nothing in the way of satisfaction for presumed expectations. The story belongs to the teller.

Criticizing the writing of a story is valid, insofar as the reader may be negatively impacted by the construction of the verbiage. But telling the creator of a fiction that they have the story wrong is ludicrous, and arrogant in the extreme. There is no value to comments such as:

Produce your own works of creative fiction, then, and let’s see who gets published more. I consider that of all the people I have met in connection with books, the least critical of an author’s work is another author. That should tell us all something. Oh, wait, I do remember something negative that Pat Rothfuss said about Brandon Sanderson. It was something like, “His stories are so good, it’s really starting to piss me off”. See what I mean?

JFKingsmill16 @@@@@ 18 did remimd me of the Chtorr which I had read and then forgotten about. I did not realize that the series still has not come to its conclusion. I just did not care after a while of not having the next book come out. 18 years is a long time to write a book.

What a great title.

One thing I feel might be different between Doctor Who and some of the other works at question is it is a longer running and collective creation.

I (and some of my friends) have discussed with anger the fact that modern Doctor Who writers have retroactively remapped the past Doctor Whos to have the companions be in love with their Doctors. If one hasn’t seen the old Doctors one might think that the sexual tension so common in the reboot was there all along rather than a recent invention.

I am annoyed by this rewriting of canon for their own ends.

Oh, and, though he gave us the wonder of Star Wars IV, what George Lucas has done with the prequals, not to mention digitally fuxoring the classics, he, while not evil, is definately a victim of his own hubris.

While some fans get too much in the way of entitlement, I do feel that a contract of sorts is created whenever you release an incomplete work into the wild, and expect people to buy it for actual money.

If a book, or film, or TV episode is “part 1 of 3”, I expect part 2 and 3 to come out before I forget the basic plot of what happened in part 1 – or, if that can’t be achieved, I want at least some kind of closure to the main storylines that were opened. If you didn’t want people to expect part 2 and 3 to come out, then you should have written the whole thing as self-contained from the start.

Of course no such contract exists on paper or in any formal way. But we expect this to happen with general goods (you wouldn’t buy parts 1 to 9 of a 10-part kit if you didn’t expect part 10 to actually come out), so why should content creators be excepted from this?

I also believe that stories, once are out in the wild, cease to be the sole property of their creators or “IP owners”. Yes, they might be able to dictate the “one and true and only canonical version” of a story (though Marvel and DC and George Lucas are obvious examples of why even that is a silly notion), but they can’t stop the readers from making up their own versions, and what-ifs, and variations – and their canon.

The last one, in particular, is so hard to concretize between fans that, when there is something that everyone accepts, and it has had a lot of time to sediment, it does feel like a cheat when the author tries to change it retroactively. “Greedo shot first” makes the fans raise their arms in anger not so much for the change itself, but because it felt like Old Lucas writing a fanfic in Young Lucas territory, and making that fanfic canon.

@ZetaStriker:

Great point. I never thought about the prequels in comparison to the novels of the expanded universe. But what do you think about this: Something that always bothered me about the Star Wars novels was an emphasis on “space politics” and then with the prequels, we got just that, more space politics. Are the early Zahn books partially to blame for all the futzing around in the senate, etc?

@32. Fuzzix

The Original Theatrical versions of Star Wars that are are on DVD are the laser Disc versions. These versions have not been digitally restored & formatted for Wide screen TVs. This means for those people who try to watch it on their 60″ wide screen it will look awful. On my 37″ standard TV it still looks good though.

@41. ryancbritt & ZetaStriker

I remember being shocked when I read the Revenge of the Sith book that there was actually a real plot and Anakin’s motivations made sense.

@42 JFKingsmill

Thanks for that clarification. On my 32″ SD CRT it looks fine, so I had assumed that everything was fine and dandy. I suppose that I’ll eventually be disappointed with the quality, but I’m guessing if I wait for Lucas to do the right thing, I’ll be disappointed anway.

@JFKingsmill16 My co-worker here at Tor.com, Emily, frequently asserts that The Revenge of the Sith novelization is full of all kinds of stuff that makes sense out of some of the things that DON’T make sense in the movie.

@Freelancer I think I tend to agree with you. However, it is interesting that even while holding the general opinion that this stuff isn’t mine, I still sometimes attempt to wrest ownership away from the creators, at least in my mind. In my case, it’s like I know I shouldn’t, but I can’t help it!

Contracts?

Guess what, in my mind you all just signed secret contracts with me! Hope you all like giving footrubs, because that’s what you signed up for.

@@@@@ longtimefan #16

I am going to agree with Jhirrad @@@@@10 and say that when an author

delivers a finished book to his publisher and the publisher says it is

too big they will have to split it into two I just expect a book in two

volumes. I do not expect that 7 years will pass because what was once

presentable by the author’s standards has suddenly become a long project

of revisions.

First, I should say that I’ve not read the work in question so my response is addressed only to this comment. The writer in me reacted to this comment by asking “Is it always that easy?” Maybe you’d get lucky and find a chapter transition that could work as the ‘ending’ of the first book and the ‘beginning’ of the second book as though the two books had been planned that way. How many writers would be that lucky?

Put yourself in the writer’s place. You’ve written and polished the story you wanted to tell only to be told that you’ve got to make that drastic change. You now have to find a way to end that first part so that it holds up as a ‘complete’ work. Then you have to find a way to begin the second part so that it too stands as a ‘complete’ work. Then you find that the changes are all too noticeable patches tacked onto the richly woven tapestry of the story you created. Or worse, you find that the changes altered the flow and/or meanings of the story to the point where you cannot be pleased with the result but you just cannot find your way back into the flow to retell the story. “I’ve already told this story. I have more to say.”

@@@@@ Scotoma #17

As for the whole “fuck Ronald D. Moore” at the end of BSG, what reaction do you expect when someone presents cultural suicide as something positive.

While the decision to end the series that season presented them with some storytelling problems, the ‘cultural suicide’ ending was not as out of the blue as most people seem to think. If you think about little things presented throughout the series – and even in the Miniseries – you might find that that ending had a solid foundation. That foundation even encludes elements of the original series.

There are those who believe that life here began out there, far across the universe, with tribes of humans who may have been the forefathers of the Egyptians, or the Toltecs, or the Mayans. That they may have been the architects of the great pyramids, or the lost civilizations of Lemuria or Atlantis. Some believe that there may yet be brothers of man who even now fight to survive somewhere beyond the heavens. – This is, of course, the preamble to the original series. A few of my friends said that they didn’t like the ending because they expected it to end with the founding of Egypt, or Atlantis or any or all ot the mentioned civilizations. However. As I see it, this one line allows for the ending we saw. with tribes of humans who may have been the forefathers of the Egyptians, or the Toltecs, or the Mayans. The key word here being Forefathers.

As I’ve made it clear in other discussions here and elsewhere, I’m one of those who loved the ending of BSG. Was it the ending I expected? No. But, it did make sense to me when I thought about it in relation to all the little things I had picked up on throughout the series.

It seems to be that there are several issues here. GRRM is about delay, Dr Who is about continuity, Star Wars is about ownership and BSG/Lost is about story-telling.

I can see that the GRRM delay must have been frustrating but there is no contract, legal or moral, between the reader and the author.

It has been argued that it was pandering to fans’ obsessions about continuity that led to the cancellation of the original Dr Who series after 40 odd years. Dr Who is a collaborative effort which needs to shift and change according to the people involved and the necessities of television. Incidentally, throughout the show’s history, its style has changed noticably when a new producer/showrunner came in.

With Star Wars, Lucas can tinker with his films to his heart’s content, it’s when he denies viewers the chance of watching the originals that he falls into error.

Finally, with BSG and Lost, the problem seems to be dissatisfaction with the conclusion. Here I think the fans are on firmer ground as both series played on expectations of mysteries being solved in a satisfactory way. It is therefore legitimate to complain if you do not think those conclusions satisfactory. It is akin to reading a novel described by the author as a detective story with the solution being that the butler did it. It is fair for the reader to complain that this is not really satisfactory.

To me, the whole GRRM affair hinged on his promises to deliver. If he had made no promises, the whole thing would have never happened. Sure there would have been frustrations and lost fans, but there never would have been a crescendo of anger if he hadn’t sounded like a weasel.

As for the remaining issues, I think fans are perfectly within their rights to judge a work in any way they wish. They are the final arbiters of success for most writers–no sales, no money. So all creators have to perform a balancing act. Once they establish their vision or are given a canon to work with, they have to risk alienating some fans no matter what they do. Again, risk vs. reward.

There is one thing that artist’s like George Lucas need to learn and that is when to stop tinkering with their own work. He just can’t wrap his head around the fact that the original trilogy was essentially perfect and almost universally loved just the way they are. In general we accept Director’s Cuts of movies because the originals are still available if we don’t like the improvements.

I’m a little confused about all the comments regarding GRRM’s “promises” to deliver. I’ve been a reader of the series for over a decade now, I’ve been fortunate enough to spend a fair amount of time with him at Cons is the past, have been a regular visitor to his website and read his Not A Blog since his first post there but I’ve not once seen him promise anything except that he was working on it and that he’d post on the website when Dragons was done.

Have I been disappointed that it’s taken so long to finish A Dance with Dragons? Yes. Am I angry with him about it, or do I feel somehow betrayed? No. Shit happens, man, and as someone who once hoped he could be a writer and in the past couple of decades watched his dreams dissipate in failure after failure, I have nothing but respect for anyone who manages to finish a novel, much less get one published. That’s a hard freaking job and whether it takes a guy 5 years or 10 to get it done my amazement at such a talent will never cease.

Fans are owed nothing by creators of the work. There is no rule that any author has a “contract” with a reader. The contract, if any, is between the book-buying consumer and the publisher. I go to the bookstore, pick up a book by “author brand x,” look it over, and pay $7.99. And if the book is bad, it generally sells poorly, and I shun that author/brand. If the book is missing pages or falls apart, I shun that publisher. Readers and fans “vote” with their wallets in consumer culture. But it is a mistake to think that the brand you are loyal to, owes you anything in return. I buy a pair of NIKE shoes — what does NIKE owe me for buying their product? Nothing. If the product is bad I am free to choose another brand next time. If I buy 100 pairs of Nike shoes, and have worn them since childhood — it still does not make for a moral contract. To think that there is some kind of obligation or moral contract between the author and the reader is ridiculous. People get mad at GRRM because they expect him to be able to produce commercial fiction the same way Pepsico produces soft drinks — endlessly, plentiful, unlimited consumption. Consumers have been “trained” by advertising and manufacturers to expect to be able to consume “on demand” and pay for pleasure. They are frustrated when fiction is not as ever-flowing and easily consumed as Coca-cola. The idea of not being able to get your pleasure right now feels like a denial of rights, but this just indicates how deeply we have been trained to consume our popular culture. Creators can be primarily motivated by selling the maximum number of products (Lucas) or by artistically crafting the product they want (GRRM, Rothfuss.) As products, books are made to be read, authors want money, and publishers seek audiences and sales. Part of what we are seeing here is the problematic result of turning authors into brands, a process that has inflated dramatically since the 1970’s. Publisher’s invest money in selling an author. It is much better for their investment return if they create a “brand” around an author, rather than advertise a single text. The problem is that we expect name brands to produce in factory-like manner. And authors are not factories — with some exceptions — like authors who have hired crews of writers under their name (James Patterson, James Frey.) A better question we should all ask is: “what is the effect of all these fans on the author and the work?” Maybe GRRM would have finished his books faster if they were less popular. Maybe fan reactions to Lucas have so rattled his confidence that he “aims for the middle” and we get sanitized vanilla myth-by-formula. I do know that artists, creators, and authors react very differently to feedback. For some artists, fan interaction energizes and activates them, for other artists, even well-meaning fan commentary leads to writer’s block.

I’d say fans are owed one simple thing–respect.

No, respect is not OWED, it is EARNED. And if you bad-mouth others, you do not deserve their respect. This works both ways – you could say the fans owe respect to the author, as well. Respect of the craft they are called to and to their creative minds. Authors do not owe anything to fans, not even a good story. They produce works that fans consume and, of course, discussion of said words is welcomed because it helps them hone their craft for future works.

When the (hopefully final) release date of A Dance with Dragons was released, I was amazed at the negative response of many fans in the comments of all the articles I read on the subject – not because I didn’t know of the controversy, but because it was obvious that these people felt like customers who had been cheated by a “merchant”, led on to believe that the “delivery date” of a product was soon, when in fact that product was far from complete. Whoever feels like the customer of an author is missing the point completely.

Reading a book is like being invited into the author’s home, like meeting his family and friends, like getting to know him intimately. More so when said author is constantly communicating with his fans, and actively engaging them. Demanding your “right” to a new book in a series is like trying to force your way inside the author’s house while his wife is still showering, and he’s not done cleaning the place up.

On the subject of managing reader expectations, I would bring up JK Rowling and Harry Potter – rarely has there been a more tongue-tied author, and she’s never been the best at communicating with her audience while working on a book, and yet that never caused a backlash from her fans. It is basically a matter of compatibility between author and readers – if you are in touch with your audience, and know what they want and expect, then you can deliver a satisfying product (even if they are not in touch with you).

@54 Lela- Nice one! I agree. Maybe that’s what I was searching for through this whole thing; a level of mutual respect between fans and creators.

I solved the problem of “is there an implied contract between the reader and the author of a multi-volume series” nearly two decades ago by mostly refusing to buy or read novel series that are not yet complete. (I’m still waiting for the concluding volume of the Tales of Alvin Maker trilogy, begun in 1987 and now comprising six novels and several spinoff stories.)

I am more receptive to open-ended series where each volume is intended to stand more or less alone such as Wolfe’s Latro novels (Soldier in the Mist et sequelae), and I have made a small number of execeptions, but in general this approach has served me well.

And Lela@54: Respect should be the default assumption in any interaction between human beings.

As far as Moffat and continuity goes, I think it is quite a jump to go from him saying that a time-travel show can’t have continuity errors to claiming that he doesn’t care about the history or the continuity of the show. Looking at the work Moffat has done, I think it is clear that he knows and cares about the history of the show, and that he was merely saying that he wouldn’t let his hands be tied by the history of the show, if a better idea came along.

Moffat inherited a program with a very long, very complicated and quite contradictory established history. It would be easy to fall into the trap of thinking that every new episode and story must be 100% consistent with those decades of old stories, and that any time they touched on a subject where there was inconsistency in the past they would have to address the past inconsistency and reconcile it. If they tried to do that, the new episodes would be burdened with details that few people would care about and story would take second place to retconning the inconsistencies that come from half a century of creative work by many different directors, writers and actors.

Moffat clearly knows all of the past history of the show, and cares deeply about it. But rather than being tied by the decisions of the past, he uses what works to make good stories for the present. Consider the recent episode “The Doctor’s Wife.” There have been several conflicting stories that the Doctor has given, in the past, about how he wound up with the TARDIS. Moffat chose one of those stories, and used it as the basis of an elegant episode that goes to the heart of the history of the show. But he didn’t worry about accounting for the other stories the Doctor has given about how he wound up with the TARDIS, as that would have distracted from the story being told.

Similarly with the regeneration limit – some old stories establish it, others seem to establish that there is no limit. Obviously the show was not going to stick with the limit, just ending when they’d used up the regenerations. But it makes sense for the show to set things up so they don’t have to do a story or arc addressing the regeneration limit, if they don’t have a story they want to tell about it.

Which goes, I think, to the heart of what fans can and should expect from creators. Respect for the history of the creation. Building on the best of that history. A willingness to let go of that history if the history gets in the way of the quality of new work. Professional level attention to detail, work ethic, and productivity.

I think we as consumers have a right to criticize anything we buy, and we have a right to communicate our satisfaction, or lack thereof, to the producer of said product whether it’s a book, a movie, or toilet paper.

@57womzilla: I don’t think I was clear, but what I meant by that comment was that if someone is out there being hateful because I am not either working as fast as they think I should or that I have not written something they deem worthy of reading, then, no, I don’t think I owe respect in that situation. Mutual respect IS what I was aiming to project there, but maybe I didn’t do it so well! :)

Edgewalker pegged it: Sanderson has received less backlash because we’re just glad the series is being finished. Yes, some of the characters seem “off”, but that’s to be expected. But I think saying his writing of the books is better than Jordan’s is unfair, though. Sanderson gets to tie up all the lose ends. That’s inherently satisfying. We would have said Jordan’s last three books were just as amazing if he’d been the one to write them.

As for the Star Wars prequils…. How could Lucas NOT receive backlash for taking an amazing series with adult dialog and inserting a character that talks like a baby and says “doo doo”? My 5-year-old might like Jar Jar, but I don’t know one adult who does. And I’m sure I’ll endure years of grief for not letting my son watch a PG-13 rated movie slapped right into the middle of a series where all the other films are PG. Uncool.

I watched the fan outcry about GRRM not finishing A Dance With Dragons, in the time they wanted, and thought the personal attacks on GRRM as regards his character as a human being, his work ethic, etc. were beyond disgusting. If this is want fandom is about now, who needs it? I know G did predict an earlier finish, but sometimes life other obligations in addition to the story just doesn’t hew to deadline. Books aren’t about instant gratification. Neither is creativity a one size fits all thing a writer or other artist can tap into at will and form a work of genius from. I think fans who think the artist is obligated to meet their expectations at every turn have a screw loose and are not fit for decent company under any circumstance.

This is a great article with some great comments! Beings that this article compares and contrasts some of my all time favorite franchises all at once, I want to at least comment on it. I don’t know how much I have to add to what has already been said, but…

Star Wars Prequels – I love them as much as the Originals, and I grew up with the originals. Are they different in tone and content? Yes, they are supposed to be that way. Is Jar Jar silly and annoying most of the time? Yes, he was written that way. In fact, I think if the Prequels would have been more like the Originals, they wouldn’t have been as good, and people would’ve complained even more (if that’s possible), saying “Lucas is so un-original and can’t he come up with any new ideas?”, or something along those lines. Oh, and by the way, my 9 year old boy and 7 year old girl love the Prequels and I see the wonder in their eyes that I had when I was their age and saw the Originals in the theaters.

George RR Martin and A Song Of Ice And Fire – One of the 10 best fantasy series of all time! Is it taking him forever to write it? Yes, so deal with it. Do you want him to pound through it and produce a mediocre product? I sure don’t.

BSG – This series was one of the better shows on television for a long time. I loved watching it and speculating on how it was going to end. When it ended the way it did, I wasn’t too surprised or disappointed. If you remember the way the original series ended, it ended with the BSG fleet encountering Earth in the then modern day – 1980’s. Even watching it then as a young kid, I didn’t find it too interesting and stopped watching it. I thought that having the same type of ending for this new version would have ruined it for me. I liked how the rag tag fleet ended up being the progenitors of the human race on Earth.

LOST – One of my favorite shows of all time! The best thing about LOST was the journey it took us on for 6 seasons. I enjoyed every season and the constant speculation of what was going to happen next. What current show is bringing this type of excitement? Maybe Fringe? People seem to be quick to complain about a show’s ending, but yet they seem to forget how much fun they had watching them for years. Surely multiple seasons of entertainment can outweigh an episode or two.

The Wheel Of Time – This is another example of years of entertainment that fans have ended up nitpicking small things to the detriminent of the whole. I’m just happy that the series is getting finished. Then to find out Brandon Sanderson was going to finish it? That was icing on the cake! Brandon definately has his own voice and style and it sometimes comes out in the characters. But what are you going to do? The story is the same, the characters are still doing the same things as they would’ve anyways and Brandon actually brought a breath of fresh air to the story that has been missing since book 6. WOT is actually exciting to read again.

So, I guess my overall stance is that things don’t end up the way you want and change inevitably happens, so you can either complain about it or make adjustments. As fans we can’t forget how much fun we’ve had consuming the overall product for X number of years, and we should take the good out of what’s there.

PS – I don’t watch Dr. Who, maybe I should start.

The real problem for me as a fan is not the delivery of a satisfying resolution to a story. The one for me is unfufilled promises. In the case of George RR Martin is was oh the next book will be out in October. No I mean December, I mean March etc… The reason so many fans including myself have not been so upset with for example Brandon Sanderson is his honesty and transparancy even when he tells us something we dont want to hear. i.e. it will be at least a year till the next book got started because he was doing re-reads. He has been very forth coming and honest with what is happening in the creative process. This takes a lot of the sting out of waiting. There is not the repeated let down of publication dates that never happen. It also helps that he is such a dedicated writer that you have several new books from him to help feed your craving for his worlds even though they are not WOT. My final word of advice to the fans be patient you did not create this universe. You are just visting it. So treat the author like you would when visting your grandparents, and be polite and patient. To writers be honest and do not make promises you can not keep. The reasonable fans (among us) will be understanding if a virus crashed your hard drive and and you lost the last 30 days of writing just tell us. Ignoring us just makes us angry and want to reach for the pitchforks and torches.

As I see it, there’s no contract on either side. On the one hand, authors do not owe fans a vote on who survives, or a prompt next novel, or anything else.

On the other hand, fans don’t owe it to authors to refrain from any type of criticism or comment (within the boundaries of the law – no stalkers please,) even tasteless “well, what if you die, old man?” remarks or short-sighted, hyperbolic internet whining.

“Social contract” may not be the right phrase to describe what happens between the creator and consumer of art, but there is certainly a relationship between the creator and consumer.

On the most basic level, the consumer wants the creator to make art, the creator wants the consumer to pay them for their art – buy their books, watch their program and the associated commercials, etc.

There is also a social relationship. Many (but not all) people who create art want it to be enjoyed by others, and enjoy getting positive feedback from people who enjoyed their creation. Many (but not all) people who consume art, who read books, watch television and movies, etc. enjoy the creative work, and also enjoy, when possible, sharing their appreciation with the creator of those works.

The social relationship also extends, sometimes, to wanting to help. That’s what humans do, after all, we create communities where we help each other with the tasks of survival and with the things that make survival a joy. Which is the issue here – fans want to say “this is good, that isn’t, this could be better, keep up the good work,” etc.

In some ways, it is a return to how stories were told through most of human existence. When people didn’t have printing, stories were told out loud, and the storyteller had their audience in front of them, and had instant feedback on what was or wasn’t enjoyed. The separation between the story creator and the story’s audience that printing, movies and television creates is unnatural to the relationship between creator and audience.

@@@@@ Myself #48

I had gotten worked up in defending the ending and forgot the part that would have tied my comment into this topic. If – and this is based on conversations with people who did not like the ending – if you as the viewer or reader dismiss and ignore parts of the story or complete episodes because you thought they were mistakes then how solid is your footing in complaining about the ending when the parts you ignored do support that ending?

When I decide to read or view some fiction the only thing I’m owed is a story to think about. Liking or not liking it is up to me. Or I can do both – as is the case with Orson Scott Card. I’m interested in the stories he tells but there is something about his telling that bothers me. Do I have a right to demand that he change things to suit me? No. He has found his storytelling voice and he has the right to tell his stories with that voice. It is up to me to decide to continue reading his stories or not to read them.

On the other hand. I feel that readers/viewers have a right to express their displeasure when a series or the final book of a manga gets cancelled – leaving the fans hanging. (A stern look in the direction of Tokyopop.)

Let me say first that having tried writing, I have a deep respect for anyone who creates good books, movies or TV shows. I also have a deep disdain for anyone putting out tripe. Writers don’t owe fans anything, but if what they put out isn’t worth the time / money spent on experiencing it, then the fans don’t owe writers their future time / money or their silence on what crap they think the product is. And if an author says something will be done in a general period of time, then it should be, just like if a contractor says your house will be done in a general period of time. If you don’t want grief over getting things done in a certain timeframe, don’t say it will be. Simple enough. If fans love your early stuff and say so to everyone who will listen, don’t be surprised when they tell everyone who will listen when you make crap.

For the record, I have watched Dr Who since the late 70’s, and enjoyed mostly all of it. I really liked the early WOT, but got bored with it and stopped reading it before Jordan got sick. I haven’t read the new novels, I’ll probably get them on my kindle after the series is done (it isn’t done yet, is it?). I never got into GRRM as an author. Lost I liked at first, but it became how I felt after the first season. I stopped watching Battlestar after it seemed everyone was ending up being a Cylon. Doesn’t sound like it ended well, maybe I’ll pick up the DVD when I have time to kill (like after surgery).