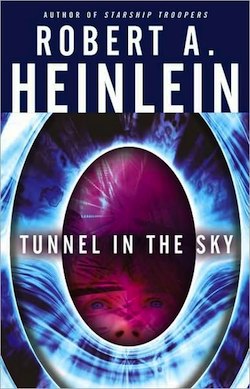

Tunnel in the Sky (1955) was originally published as a juvenile, but I first read it in a Pan SF edition clearly aimed at adults. But these things are tangled; I was a teenager at the time. Some of Heinlein’s juveniles are more juvenile than others—this is one of the more mature ones. This is a future Earth with massive overpopulation, and with faster than light gates providing instant transportation between points. Gates between different places on Earth are kept open and you can walk anywhere. Gates to other planets are expensive to run, and food and fissionables are scarce. Still, other planets are being colonized rapidly by pioneers, some voluntary, some not so voluntary. Rod Walker needs to do a solo survival trip to qualify for any off-Earth job, and he’s taken the course in high school to save time in college. Of course, that’s when things go wrong.

It seems obvious that Tunnel in the Sky is a direct response to William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (1954). Indeed, I imagine Heinlein putting down Golding’s book and heading straight for the typewriter grinding his teeth and muttering “Revert to savagery my ass!” The two books make a perfect paired reading—they have such opposite views of human nature. Which one you prefer will depend on your views on humanity. For me Tunnel in the Sky is a frequent re-read, and I doubt I’ll ever read Lord of the Flies again.

Heinlein’s characters have learned the trick of civilization. He knows that people can be savage—Rod is attacked, robbed, and left for dead on his second day on the alien planet. There’s talk at the beginning about man being the most dangerous animal. But Heinlein also believes that people can co-operate. His stranded kids, who are aged between sixteen and twenty-two, start to rebuild technology, get married and have babies, practice square dancing and treasure the Oxford Book of English verse—while hunting for game and wiping out predators.

It’s interesting that Heinlein doesn’t begin the book with Rod stepping through the gate and beginning the test. It’s the part of the book that’s memorable and effective—Robinsonades are always appealing. There are the challenges of learning the environment, and the political challenges of building a society. But while Heinlein was always easily seduced by pioneering, he’s doing something more. This is a novel of how Rod grows up, and of how growing up isn’t always comfortable, and it needs the beginning and the end to do that. Heinlein shows us a great deal of the world Rod is leaving, before we get to the world where he’s going. We get Rod’s parents and sister and teacher and the whole context of the world he comes from. The best part of the book may be the challenge of being stranded on an alien planet, but the whole book is better for having the shape and structure it does.

I want to give Heinlein props for several things here. First, he doesn’t duck the FTL = time travel issue, the gates can also be used for forward-only time travel, and they were invented by somebody trying to invent time travel. Also, we have a lot of SF with very standard FTL resembling Napoleonic sailing ships. It’s nice to see something where you can walk between planetary surfaces.

Next, many of his juveniles are deeply lacking in females—Tunnel in the Sky is much better. The main character, Rod, is male, but there are two significant female characters, Jack and Caroline. Caroline is the best character in the book, and some small parts of the book are her clever and funny diary entries. It very nearly passes the Bechdel test. In addition, while many of the girls get married and have babies, there’s no coercion along those lines. Caroline remains unattached, and nobody tells her she should be having sex and babies for the good of the human race.

But while the gender stuff is really well done for 1955, it’s still considerably old fashioned to a modern reader. Helen Walker, Rod’s sister, is an Amazon sergeant—but she’s eager to retire and get married if anyone would have her. She later carries through on this, so she clearly meant it. Caroline also says she wants to get married. Rod is forced to change his mind about girls being “poison” and disruptive to a community, but we have very conventional couples. There’s a lot of conventionality. Although women work, Grant doesn’t want girls to stand watches or hunt in mixed gender pairs. He does back down. But when Rod makes his exploration trip, it isn’t Caroline he takes with him. And while it was certainly progressive to have women in the military at all, why are the Amazons segregated?

As usual, Heinlein is good on race up to a point. Jack is French, and Caroline is a Zulu. There’s a girl mentioned called Marjorie Chung. It’s also worth noting that Rod is very likely African-American—Caroline is referred to as a Zulu and has a Zulu surname. Rod’s surname is the very American Walker. But when describing Caroline to his sister he says “She looks a bit like you.” The point where this stops being good is that while Heinlein goes out of his way to have people of many ethnicities they are all absolutely culturally whitebread American. You can be any colour as long as it makes no difference at all. If Caroline’s a Zulu and Jack’s French, they are still both entirely culturally American. It’s a very assimilated future, even if China has conquered Australia and made the deserts bloom.

However, religion is treated very well. The count of books is “6 Testaments, 2 Peace of the Flame, 1 Koran, 1 Book of Mormon, 1 Oxford Book of English Verse”. “Peace of the Flame” is the holy book of the fictional neo-Zoroastrian sect that the Walkers belong to. What we see is quiet religious practice that is in no way Christian, treated respectfully and effectively. I like that Koran. It’s never mentioned who it belongs to. Bob Baxter is a Quaker, and in training to be a medical minister—again this is quietly accepted. Religion is so often entirely absent from SF set in the future unless it’s the whole point of the story, it’s nice to see it treated this way, as a natural small part of the way some people organize their lives.

I love the stobor—both the imaginary stobor they are told to watch out for to keep them alert, and the ones they build traps for. I love everybody saying they wouldn’t go back—except Bob, who sensibly wants to finish his medical training. I love the end, where the whole experience is just a newsworthy sensation to crowded Earth. I really like the way it doesn’t have a conventional happy ending—that everyone does leave, and that Rod has to fit himself into a space he has outgrown to get the education he needs to do what he wants to do. I also like that there’s sex and romance but only off to the sides—Rod and Caroline don’t get caught up in it. I know Heinlein did this because it needed to be suitable for children in 1955, but now that it’s obligatory for protagonists to have sex and romance I’m starting to value books where they don’t.

There’s a lot that’s absurd, of course. The overpopulation—Rod lives in Greater New York, by the Grand Canyon. The idea that this overpopulation could be relieved by emigration—it seems like it would be news to some people that the population of Europe is higher than it was in 1492. The idea that opening the gates is expensive so taking horses and wagons makes sense for low tech colonization—this is just silly. Yes, horses reproduce and tractors don’t, but there’s absolutely no reason not to take along a tech base and farm more efficiently. But this is far from the focus of the book—they’re managing even more primitively because they got stranded on a survival test, and that makes perfect sense.

I don’t know how it would strike me if I read this now for the first time. I suspect I’d find it thinner—Jack is barely characterised at all, an awful lot of her characterisation is in my head and not on the page. But I think it would still catch me up in the essential niftyness of the story. I thoroughly enjoyed reading it again, and even the absurdities are vividly written—the description of Emigrants Gap is lovely. It’s possible to learn a lot about incluing and how to convey information to a reader by examining how Heinlein did that.

There’s a Locus Roundtable pouring scorn on the idea that Heinlein juveniles have anything for today’s young people. All I can say is that it’s twelve years since I read this aloud to my son and he loved it, maybe times have changed since then.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.