In a bar last week, a man I’d just met was telling me all about how Gene Roddenberry wrote an episode of The Twilight Zone. Not wanting to offend the guy, I gently said I was 100% confident that Gene Roddenberry never wrote for The Twilight Zone. My new friend insisted I was wrong, betting me a beer that Roddenberry wrote the episode about the “electric body.”

“You mean, ‘I Sing the Body Electric’?” I said.

“Yep. That’s the one. Best episode. Roddenberry.”

“Bradbury.” I said.

“Yep. Roddenberry.”

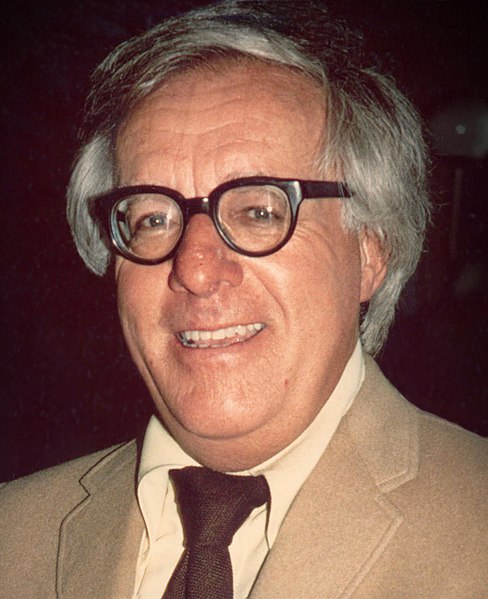

Though I never did get the beer out of the guy, the unrelenting fame and ubiquity of Ray Bradbury did , once again, occur to me. Like Vonnegut, Bradbury enjoys a great deal of genre crossover appeal. Though my barfly friend was confused about names, he was also familiar with the other Bradbury titles I rattled off (though still attributing them to Roddenberry.) The point is, everyone has heard of Ray Bradbury, even people who know nothing about science fiction. But why? Was Bradbury the original genre buster?

It’s hard to overstate the abundance of material Bradbury has produced. Though he hasn’t dominated nearly every category of the Dewey Decimal system like Asimov, the man has put out a tremendous amount of work. He also has a great deal gravitas with the mainstream owing largely to the immense popularity of Fahrenheit 451. Notably, Bradbury recently allowed this famous novel to be distributed digitally, a notion he resisted for quite some time. I’m sure he was probably the least delighted of anyone in the world by the brand names “Kindle” or “Fire.”

Regardless, Fahrenheit 451 has the kind of fame of a novel like To Kill a Mockingbird insofar as it tops tons of high school and undergraduate reading lists. These kinds of reading lists are often lousy with cautionary tales, so this is unsurprising. Further, as I’ve pointed out before, exceedingly grim, or depressing SF novels like 1984 or Fahrenheit 451 have a somewhat easier time grossing genre divides than other kinds of SF. And yet, Bradbury’s other work is far more upbeat than his famous book burning dystopia. Unlike the traditional novel structure of Fahrenheit 451, the format Bradbury more commonly employs is that of a series of vignettes which form a larger narrative or thematic point. He does this most notably with The Martian Chronicles, The Illustrated Man, and Dandelion Wine.

Regardless, Fahrenheit 451 has the kind of fame of a novel like To Kill a Mockingbird insofar as it tops tons of high school and undergraduate reading lists. These kinds of reading lists are often lousy with cautionary tales, so this is unsurprising. Further, as I’ve pointed out before, exceedingly grim, or depressing SF novels like 1984 or Fahrenheit 451 have a somewhat easier time grossing genre divides than other kinds of SF. And yet, Bradbury’s other work is far more upbeat than his famous book burning dystopia. Unlike the traditional novel structure of Fahrenheit 451, the format Bradbury more commonly employs is that of a series of vignettes which form a larger narrative or thematic point. He does this most notably with The Martian Chronicles, The Illustrated Man, and Dandelion Wine.

Other than allowing Bradbury to write these stories individually and then cobble them together into a novel later, there’s another advantage to this format: it’s accessible. A large sprawling world-building heavy SF novel is daunting to a reader who might be on the fence about rocket ships and aliens. Bradbury dispenses with this problem in The Martian Chronicles by using the connected vignette format. Not sure you want to read a whole book about people settling on Mars? That’s okay, just try this one short story and see if you like it.

The other reason this approach creates a crossover into mainstream readership is that a novel in stories is inherently perceived as literary. That’s because there’s another level of artistry to pulling it off beyond just the writing. Sure, the framing mechanism of the Illustrated Man in The Illustrated Man might seem a little hokey, but it’s fun for the reader to think about how all these stories are coexisting together on someone’s body. And in terms of the way we worry about continuity in novels, a collection of connected stories allows for some of that worry to dissipate. In short, Bradbury was not a novelist, he was a spinner of short yarns, which when he allowed free association, came together in some kind of larger whole. He cops to it in his essay “The Long Road to Mars” which deals with how The Martian Chronicles came to be. In it, he relates a conversation between himself and a publisher at Doubleday serendipitously named Walter Bradbury. The two are having breakfast and Ray Bradbury is telling Walter that he doesn’t have a novel in him. Walter responds:

“I think you’ve already written a novel.”

“What?” I said, “and when?”

“What about all those Martian stories you’ve published in the past four years?” he replied. “Isn’t there a common thread buried thre? Couldn’t you sew them together, make some sort of tapestry, half-cousin to a novel?”

“My god!” I said.

“Yes?”

“My god.”

Bradbury goes on to say that he may have never put out The Martian Chronicles if it weren’t for this conversation, which for my money, put Bradbury on the path to having genre crossover. He in way, he pioneered a novel as stories and made it a viable and vibrant concept. Would we have novels like Cloud Atlas or A Visit from The Good Squad now if it weren’t for Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles or The Illustrated Man? I think the answer is definitely no. The act of messing with the format of what a novel is or is supposed to be is part of what speculative fiction is all about. A novel in stories is sort of like reading a novel from an alternate universe.

Bradbury goes on to say that he may have never put out The Martian Chronicles if it weren’t for this conversation, which for my money, put Bradbury on the path to having genre crossover. He in way, he pioneered a novel as stories and made it a viable and vibrant concept. Would we have novels like Cloud Atlas or A Visit from The Good Squad now if it weren’t for Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles or The Illustrated Man? I think the answer is definitely no. The act of messing with the format of what a novel is or is supposed to be is part of what speculative fiction is all about. A novel in stories is sort of like reading a novel from an alternate universe.

Famously, Bradbury had no real aspirations to be well respected or well thought of in literary circles, and constantly made a point to talk about how writing simply made him happy. Proof? The first essay in Zen in the Art of Writing is called “The Joy of Writing.” Despite some of his dark cautionary tales, Bradbury himself seems to usually rally for a more upbeat approach the art form of prose. Ray Bradbury is not a tortured artist and mostly wants you to have a good time reading his books. Sometimes this has tricked a mainstream readership into some magical realism, and sometimes into some horror. And other times, it’s put them on a rocket to Mars, whether they wanted to go or not.

Because Bradbury’s books are so numerous, recommending the various titles I’ve mentioned above seems a bit pedestrian. Instead, I’ll say if someone enjoys books which skip in and out of genre, or like short story collections which seem to have an overall point (if not a connected story) then you can’t go wrong with Bradbury’s 2004 collection The Cat’s Pajamas. I’ll not ruin a single story for you in this collection. But it’s worth looking at, if only to remember the other important thing about Bradbury; he’s never stopped writing.

And for the final proof that Bradbury has the most mainstream appeal of any SF writer: there’s a reason why this video exists:(Totally NSFW, but also great.)

Ryan Britt is the staff writer for Tor.com. He is the creator and curator of Genre in the Mainstream. His inials are also RB.

“. . . he pioneered a novel as stories and made it a viable and vibrant concept.”

Yeah, really have to disagree. Not only did van Vogt and Vance publish other fix-ups (as they’re rather awfully known) in 1950, Sherwood Anderson had published Winesburg, Ohio in 1919 and Faulkner Go Down, Moses in 1942, and there are plenty of even earlier examples of story-cycles (Dubliners, The Piazza Tales) and of highly episodic novels (Huck Finn, just to pick one out of hundreds).

Nor am I certain the influence on Cloud Atlas and A Visit from the Goon Squad is particularly direct or profound. I’d guess that both Bradbury and Egan were thinking of Proust when they wrote (and Egan’s epigraph says I’m right on at least one of those). As for Mitchell, I think there is a stylistic similarity, but I’m not certain where it comes from. (Mitchell loves Haruki Murakami, though, and Murakami is quite Bradbury-ish in that he marinates in bittersweet nostalgia; I wonder if that’s the connection?) Ultimately, though, I don’t think that speculative fiction can take much credit for literary experimentation–at least not more than other genres. Certainly there’s a whole hell of a lot of experimental SF/F/H/whatever about, but such works have frequently been at least partially pastiches or parodies of earlier works (“Riders of the Purple Wage” springs to mind). So I don’t know that we’ve tended strongly toward original formal invention. Certainly speculative fiction has produced genuine innovation, but it seems a bit of a stretch to say that “A novel in stories is sort of like reading a novel from an alternate universe.”

(On a related note, Wikipedia tells me that 1950 was the year of the fix-up. The Dying Earth! And the year after that Foundation and I, Robot! And then City! And then More Than Human! All right, I’m done.)

@1 Fair points. However, I’ll go ahead and say that I feel like Dandelion Wine and The Martian Chronicles specifically have more in common with contemporary genre crossover books (like Goon Squad and Cloud Atlas) than something like The Dubliners, or even I, Robot. And I think it has to do with the emotional punch of how all those vignettes hang together. But that’s hard to articulate, and maybe I didn’t do it as well as I could.

I don’t think Bradbury invented what we’re talking about, but I think he popularized it in a subtle way and that is a factor as to why he’s so widely read. People on both sides of the genre divide read some of these books, which isn’t the case with I,Robot. As much as I LOVE I,Robot it feels more like patchwork more than The Martian Chronicles.

ALSO, I guess my overall point isn’t if Bradbury invented this kind of thing, or if he did it better, but more that I think it is a big part of why he crosses over. So I suppose I would entertain conceding everything you’ve said, but sticking to my rayguns on that one. :-)

Having been a rather intense Science Fiction reader as a youth, I never once considered Bradbury a SF writer per se, but rather an eclectic writer who sometimes wrote SF. Several of the authors I read at that time fell into this category.