There are so many levels at play in The Man Who Fell to Earth, it might just topple your head from your shoulders.

The title was originally a 1963 novel written by Walter Tevis, lauded by many as an exemplary genre work, one which employs allegory and real-world exploration to a truly stunning degree. It is the story of an alien, Thomas Jerome Newton, who comes to Earth looking for a way to save his dying species. What he finds instead pushes him into a downward spiral of alcoholism and despair. The book was adapted into a film of the same name in 1976, directed by Nicolas Roeg.

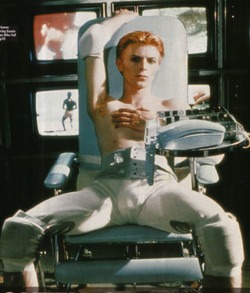

It was also the first film to star David Bowie.

Fresh off the Diamond Dogs tour and ready to shed his more ostentatious glam trappings, Bowie came onto The Man Who Fell to Earth project with a head full of soul music and a body full of cocaine. One might assume that it made him hell to work with, but all accounts of filming indicate the exact opposite—that Bowie and Roeg got along famously and the rock star was more than happy to do his share of the heavy lifting, despite being high as a kite throughout.

The truth of the matter is, Nic Roeg was a lucky man (and likely knew it, too). Because at that point in David Bowie’s life he was Thomas Jerome Newton, the man who fell to earth, and it comes through in every shot of the gorgeous cult classic.

The parallels between the two (and, to a lesser extent, Bowie’s neglected Ziggy Stardust stage persona) are manifold: a man who achieves great notoriety and fame, allowing people glimpses of the future through his inventions or innovations. He is sidetracked by substance abuse and a growing disconnection with the world, exacerbated by public attention and a perception by some that he is “dangerous”. His relationships dissolve (Bowie’s marriage to wife Angie was on its way out at this point), and he’s eventually ruined. Thankfully, Bowie managed to pull himself out of that hole, but during the making of this film, that remained to be seen. He was on the downhill slide, barely keeping up a pretense that he was still involved with the real world. Every line delivery, every expression he lends Newton imbues the character with more than just an honesty; this might as well be a movie Bowie wrote in a coke-addled fugue, trying to convey his pain and hopelessness to the masses.

There are many other elements to recommend this film to anyone who appreciates good science fiction or movies with a more surreal take on cinematography and time progression. Nicolas Roeg made a career out of his unique eye and framing techniques—he was the cinematographer for Fahrenheit 451, and director of Don’t Look Now and Walkabout, to name just a few credits. As such, I feel that the film demands more than one viewing; there are pieces that one might naturally miss while your brain is busy compensating for jumps in the narrative, changes of location, interesting choices in imagery.

It is a film that manages to be its own entity while honoring the book it came from entirely. The changes made are not the sort that we’ve grown to expect from Hollywood whenever they inherit a text that contains any ambiguity, moral or otherwise. Rather, the changes seem to be designed to invoke a sense of isolation that is frightfully effective. In the novel, Newton’s species and planet has been decimated by nuclear war. His plan is to rescue the 300 left by creating a ship that can travel home to get them; then the aliens plan to infiltrate Earth’s government structures to ensure that humanity doesn’t make the same mistakes they did. In the film, Newton is simply sent to Earth to recover water for his drought-ridden planet—the reason why his home is facing this hardship is never made clear. The lack of instruction from his own people, and the fact that the only other aliens we see in the film are Newton’s own family, make Newton seem far more alone in his quest.

The love interest of the film serves a similar function. In the book, Betty Jo (called “Mary-Lou” in the movie, to make matters confusing) has no intimate relationship with Newton. Adding a romance could have been a cheap shot at attracting a larger audience, but instead it proves how separated Newton finds himself from humanity. When he finally reveals that he is an alien after years with Mary-Lou, she reacts in horror and their time together ends. Their brief, desperate affair toward the end of the film drives the point home; they don’t love each other, but this is what she taught him to do when they first met—drinking, mindless entertainment (who loves them some table tennis?), and sex.

It reflects poorly on humanity as a whole, as do the choices made by the government in their destruction of everything Newton has worked for. They even murder Newton’s business partner, Oliver Farnsworth, a character who was further developed in the film, shown to be a gay man. His death contributes to another overarching theme—in society, everything alien (and every SF fan knows “alien” is really just another way of saying “different”) must be destroyed. The government’s treatment of Newton echoes Cold War fears and even shadows of McCarthyism all in one go, something that the book was more vocal on.

But perhaps the most interesting change is one that I find alters my perception of the whole story. In Tevis’ work, Newton is experimented on by the FBI and CIA and during one of the sessions, they x-ray him. Newton’s species are sensitive to x-rays and the act blinds him. But in the film, the issue is not one of bodily harm; Newton wears full-eye contacts to prevent people from seeing his alien eyes and the x-ray fuses the contacts to them. Rather than being blinded, we are left with a broken man who is no longer capable of showing his true form to anyone. Keep in mind (though I’m sure you haven’t forgotten) that David Bowie is playing this part, and it is a startling slap in the face to think of how many levels that particular point operates on:

How could Newton maintain his connection to home and his family when every evidence of his alienness had been stripped from him? How could Bowie feel the need to be present for the people around him when cocaine was offering him an alternate route through life? How could Ziggy Stardust continue to be relevant in a time when his presence was being slowly relegated to a freak gimmick, a mask of clever convenience? The act of ruining Newton’s eyes in the film ends up being so much more powerful than blinding him in the novel because it is not the loss of a sense; it is the loss of self, and it can never be recovered.

What else is there to say? I’ve barely scratched glass here. There is simply too much to account for, to much to pull part and examine under dim lights in the middle of the night when you’re feeling pensive and too tired to sleep. If you’re in the mood, I encourage you to play the game, and enjoy Bowie’s performance while you’re at it. He’s the most beautiful—and certainly one of the most affecting—aliens you will ever see on film.

Emmet Asher-Perrin can’t believe she actually discussed this film without once mentioning that David Bowie gets naked in it. You can bug her on Twitter and read more of her work here and elsewhere.

I recently had the chance to re-see this film projected at a local arthouse thetaer. (Apparently this was the UK edit, a bit longer than the US release.) The first time I watched the movie, on VHS, it did not work for me. I don’t know if it was my youth, that it was the US version, or the medium, but I didn’t care fot it at all. Being thirty years older I decided to give the film a go projected and this time I got a lot more out fo it and enjoyed it a lot more.

One accidently humour moment sticks out for me. The film follows Newton through a life time on Earth of easily thirty years or so. Meaning it stats mid-seventies and ends early 2000’s. Near the end of the film Rip Torn’s character wander through a music store filled with vinyl LPs, and the audience I watched with tittered as one. The dangerous of near-term SF,

Re: the vinyl issue, it could be argued that the arrival and dominance of World Enterprises in the world of the film overwhelmed the other technology companies and prevented the development (or success) of CD. Presumably people were buying those big ball bearing albums instead. At the end of the film WE has been taken over/broken up and vinyl has returned, or is still holding its own against the ball bearings. A greater anachronism is the prices of the albums which are still at mid-70s rates. Regarding vinyl generally, as a graphic designer I’m working on more vinyl designs than ever, it’s certainly not a dead format.

Lastly, I’d give some credit to Paul Mayersberg for his adaptation of Tevis’s novel. Mayersberg and Roeg later worked together on Eureka.

It’s a wonderful book – I’ve somehow never got around to checking out the movie.

Your mention of the changes made in the movie made me want to wail in despair though – when are aliens going to realise they don’t need to make desperate interstellar trips just to borrow a litre of water?

I remember an old interstellar trading board game where the unique item that one went to earth to collect was music videos. That seems much more plausible.

Never read the book; saw the film though, and was impressed.

Found the expressed reason – water shortage – unimpressive. If they’d kept the book’s nukewar focus, it would’ve been even sharper.

When Philip K. Dick saw The Man Who Fell to Earth he felt it uncannily matched the “visions” he was having and bought all of Bowie’s albums looking for hidden messages. He didn’t find any messages but based the Eric Lampton character in Valis after Bowie. Or so the story goes.