Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the 30th installment.

After Alan Moore’s growing disillusionment, and then his departure, from DC Comics and its superhero environs, one of his next steps as a comic book writer was to do something antithetical to the “mainstream” comics he had been writing: he’d self-publish a twelve-issue hard-reality series about the erection of a bloated American shopping mall on the outskirts of a small British city. The topic was far from commercial, and the format was unconventional: square, glossy paper, cardstock covers, each issue at 40 pages, and each page built on a 12-panel grid.

To make matters even less attractive to the stereotypical superhero fans who liked how cool Rorschach was or how extreme The Killing Joke turned out to be, Moore structured the story and its central theme on the work of mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, specifically his work on fractal geometry and chaos theory. (It was 1990, and chaos theory was still years away from entering the public consciousness with the publication of Michael Crichton’s Jurrasic Park.) Originally, Moore was going to call this series The Mandelbrot Set, in tribute to its inspiration, but apparently the subject of the tribute preferred that Moore chose another name.

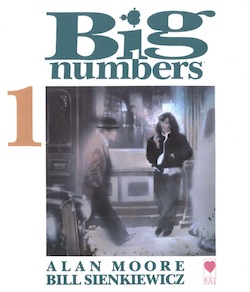

And that’s how Big Numbers came to be, with the back cover of each issue proudly blocking out the numbers 1 through 12, decoratively, in black and white, while the number of each current issue would radiate with color, setting it apart from the other eleven numbered boxes. The series was to be Moore’s masterwork, pushing comics in a new direction, accompanied by the stunningly versatile artwork of Bill Sienkiewicz, an artist who had stunned the comic book industry with his rapid visual growth from Moon Knight to the indescribable Elektra: Assassin.

Only two issues of Big Numbers were ever printed. It remains Moore’s most famous abandoned project.

Big Numbers #1-2 (Mad Love, 1990)

Such is the power of Big Numbers, as a concept, as a symbol for what might have been, that in the circles of Alan Moore academia, it has almost as much significance as Watchmen or Marvelman. In its not-even-close-to-completed state, it falls far short of either of those two works in execution, but I suspect that anyone who sits with Moore for any length of time, and has a chance to talk about his comic book career, would be most curious about those three comics, in that order: First, Watchmen, then Marvelman, then Big Numbers.

Had it been completed, it very likely could have fallen into the same category as From Hell, as a great book, rarely discussed in any depth.

But because Big Numbers remains unfinished, and will never be finished (according to everyone involved), it retains its aura of potential magnificence. Of what might have been.

The production history of the comic only adds to its legend. Released at a time when Moore had been unofficially anointed the greatest comic book writer in history (a distinction he may very well still hold, even after all these years), self-published into an industry that was dominated by superhero comics, the first issue of Big Numbers sold approximately 60,000 copies. That is a more-than-respectable sales figure for a black-and-white, small press, non-genre comic book at the time. Today, it would be considered practically a blockbuster, when comics starring Iron Man or Superboy barely crack 30,000 copies sold.

And it was thought of as the herald of something important. “Here’s Alan Moore,” the comic seemed to imply, by its very existence, “doing what he really wants to do in the medium, without corporate restrictions or commercial concerns.” How could the greatest comic book writer in the world, writing the comic he most wants to write, without any outside interference, possibly be anything less than mindblowing?

We’ll never know, because behind-the-scenes troubles with Moore’s Mad Love production house (basically, Moore’s family and friends), and then the departure of artist Bill Sienkiewicz left the project in the lurch. Except, not quite! Because Kevin Eastman, flush with Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles money he funneled into his gloriously doomed Tundra Publishing venture, was on hand to rescue Big Numbers and keep it going. And even the loss of Bill Sienkiewicz wasn’t a fatal blow, because artist Al Columbia, who had worked as an assistant to Bill Sienkiewicz, was hired to draw the now-Tundra-produced series.

All those plans, and safety nets, and readjustments, well, they all turned out to be a disaster. Eastman threw money at Columbia, and Columbia never even submitted artwork for a single issue. Sienkiewicz had already drawn all of issue #3, and though it was never published, photocopies of the hand-lettered pages have popped up around the globe and, luckily-for us, online.

Big Numbers was destined to only last two issues. And Al Columbia was barely heard from again.

Columbia, whose only major comics work since the Big Numbers debacle was 2009’s critically acclaimed Pim & Francie book, actually talks in depth about his side of the Big Numbers/Tundra fiasco in a lengthy interview with Robin McConnell on the Inkstuds podcast. It’s well worth a listen. And for even more context, a vintage Kevin Eastman interview at The Comics Journal provides a glimpse at what happened with Tundra as a publishing company, and a blog post from last year gives Bill Sienkiewicz’s reasons for leaving the project to begin with.

Clearly, the circumstances surrounding the aborted Big Numbers series are more interesting than the actual comic itself, which is why I still haven’t even mentioned anything about the plot or characters inside each issue.

In a not-insignificant way, rereading Big Numbers is about a lot more than looking at its 80 published pages, and then glancing at the 40 additional pages available online. Rereading Big Numbers is about rereading the process of its creation, abandonment, and failure. The whole scenario acts as a kind of dividing line between Moore’s great works of the 1980s what most readers still think of when they think “Alan Moore comics” and everything that followed. In retrospect, it’s easy to put the blame on the fallout from Big Numbers as the reason for Moore’s apparent decline as a comic book writer. His popularity was never as high as it was when he launched Big Numbers, and much of his work in the 1990s seems like a reaction to what he had wrought in his pre-Big Numbers career. The sophisticated comics of Alan Moore were replaced by the weirdly pandering comics of Alan Moore. His work on Spawn and Violator seems like an Andy Kaufmanesque practical joke compared to what he had shown himself capable of before. Had Big Numbers broken Alan Moore in some fundamental way? It seemed so at the time, when looked at from a distance.

But, of course, that’s too simplistic a reading of Moore’s career, by a longshot. The truth is, some of the same stylistic flourishes he started to attempt in the pages of Big Numbers the “psychogeography” of a single city, the interlocking narratives spiraling around a single event, the rejection of traditional genre tropes these all still happened, but they trickled out in the form of the From Hell chapters over the course of more than half a decade. In almost every artistic sense, From Hell was what Big Numbers was heralded to be, it’s just that it didn’t get the same notice at the start, and it didn’t feature Bill Sienkiewicz paintings on glossy, square paper.

And though Moore’s later career and I’m looking forward to rereading a lot of the later stuff, honestly, both good and bad bounced into the realm of the absurdly juvenile with the likes of Violator vs. Badrock and Voodoo: Dancing in the Dark, he also produced some fascinating bits of deconstruction with Supreme, and inspired genre work like Top 10 and League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

But what of Big Numbers itself? I suppose I should talk about the comic a bit before I close out for the week.

I wouldn’t say Big Numbers is worth reading on its own, in the unfinished state left to us. Moore’s mathematical structure is implied early on, with a young skateboarding teenager referencing chaos theory in the most memorable scene in issue #1.

As Sammy rushes out the door, his dad asks him, “Is your book good now?”

“S’great,” replies Sammy. “Apparently, life is a fractal in Helbert space.”

“Ah, well,” says his father, alone in his easy chair. “I knew it’d turn out t’be somet’in like dat. I knew dat couldn’t be right, about de bowl o’cherries.”

The first two issues and what we see online from what would have been issue #3 are made up almost entirely of scenes like that. Two people talking, possibly elliptically, and not really understanding each other fully. Most scenes don’t have the sad laugh-track-ready button as the scene quoted above, but there is a real attempt by Moore to capture the human condition in a simple, humble way, without any of the theatrics of his more famous work, and without any of the narrative tricks that he relied on in the past.

Gone are the cinematic transitions between scenes. Gone are the layered, almost multi-media narrative elements like diary entries or fake excerpts from real-sounding books. Gone are clear semiotic indicators of characterization.

Instead, Moore and Sienkiewicz give us dozens of characters, living in the same airspace and likely overlapping around this business of the new mall coming to town, and that’s it. As Sienkiewicz says when he comments on his role in producing Big Numbers: “Working with Alan was like going from the multiplication table to the periodic chart to quantum physics all in the space of one panel border.”

He means that as a compliment, and, in his recounting of events, he didn’t leave the project because of its complexity, but there’s no doubt that Sienkiewicz was pushing himself to satisfy the requirements of Moore’s scripts in a way that kept him engaged as an artist. The unpublished pages for issue #3 show a looser approach than Sienkiewicz uses in the first two issues, and given the artist’s tendency toward expressive, frenetic work in the past, it’s impossible to imagine that, even if he had stuck with the project through issue #12, the rigid confines of Alan Moore’s intricately designed pages would have lent themselves to what Sienkiewicz does best.

For Moore’s part, though he never finished the scripts past issue #5, he had the entire series mapped out from the beginning. On a massive chart, which is reproduced at much smaller scale in Alan Moore: Storyteller, we can see what would have happened to every character in every issue. Across the horizontal axis, Moore has columns for each issue, one through twelve. On the vertical axis, every character is named, and given a row all their own. Each box is filled with a tiny description of what’s going on with that character in that issue, internally and/or externally. Of course, with dozens of characters and only 40 pages per issue, not everyone would appear in every issue, but they all get a box, filled with words anyway. Because their lives continue, issue to issue, even if the comic doesn’t put them on the page at all.

The young skateboarder, who Moore identifies as “skateboard kid Samuel ‘Sammy’ Portus,” for example, would have become involved with some “brilliant computer fraud” by issue #8, and by issue #12, he would have explained fractals to a poet and a reporter and teamed up with them “and sets off in search of a new world.”

There’s something like that for every character. Meticulously structured, gridded out for Moore to see even before he wrote the script.

As Moore explains, in The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore, “I was trying to give as I’d given in Watchmen my view of how reality hangs together, a worldview. With Watchmen, there is this worldview made up of telling sentences of dialogue or imagery where you suggest a lot of kind of subtle, hidden connections that even the characters can’t see. With the work in Big Numbers it was a different sort of worldview. I was trying to come at it from a mathematical point of view, with a poetic eye on the mathematics ”

And, in the end, the commercial interests would have destroyed the city a setting that Moore reports was a thinly veiled analogue for his hometown of Northampton, England. As Moore reports in another section of the above interview, “Completion of the mall would completely wreck things and disfigure the community that had previously been there completely alter it forever.”

What we’re left with then, is an unfinished story where the mall never was completed. The community, then, wasn’t destroyed, because Big Numbers stalled at issue #2.

But that notion of corporate interests, of old-fashioned greed and exploitation, leaving a devastating mark? That lingers in Moore’s work. It lingers in every conversation that surrounds Moore’s work.

Was Big Numbers, then, an allegory about his relationship with the American comic book industry? Maybe. But though the allegory was never completed, and the mall never built, in our reality, the story-behind-the-story marches on. A gaudy new shopping center is popping up, on the front lawn of Alan Moore’s career, as I write this today. It’s called Before Watchmen, and Alan Moore will be standing outside, providing fair warning to the customers to stay away, to avoid the greed that has fueled its construction.

NEXT TIME: More possible allegory? Alan Moore explores the price of careerist impulses in A Small Killing.

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.

This is kind of a petty side note, but I’m pretty sure Jurassic Park came out in 1990. So chaos theory was sort of in the air at the time.

Moore doesn’t go entirely without tricks in Big Numbers. He keeps his “character says something ostensibly banal in dialog which, interpreted literally, encapsulates a major theme of the work” one.

(“I think that people should be able to communicate without using language” is exactly the same kind of thing as “I think Madness is better than the Police”)

Is this re-read going to stick exclusively to comics, or are we going to get a week on Voice of the Fire? Because I think that that book was Moore’s second run at what he was trying to do with Big Numbers, in a lot of ways…

I’ve been meaning to go back to Voice of the Fire after I read that even Moore himself, in retrospect, thinks the first chapter is too much to ask of the reader.

I feel like in focusing on the production history, and some of the parallels with From Hell, you ended up giving unnecessarily short shrift to the content.

I mean, sure, whether something is “worth reading on its own” is a matter of taste… but it’s hard for me to imagine thinking that that brief bit of dialogue with the fractal reference was “the most memorable scene in issue #1”. The issue opens with an eight-page wordless sequence alternating between a train trip, a nightmare, and two vandal kids getting ready to smash the train window– it’s suspenseful, it ends with a bravura full-page splash followed by a joke about the “need to use language”, and it didn’t resemble anything I’d ever seen in comics at the time.

Just in formal terms, I think the kitchen scene in #2 is pretty notable too. I don’t know how to describe that layout, but it manages to be cinematic and anti-cinematic at the same time: the whole page is a single image chopped into 12 panels, there’s no “camera” motion, but the characters and dialogue happen to move through it in a way that makes each panel work perfectly if you read them in the usual order. There’s no particular reason why that visual/narrative device had to be deployed at that specific point in the story, but it worked beautifully at that point, and the comic kept trying out different structures and styles like that every few pages in a way that I found really involving– it made the world feel layered and textured and diverse in a way that’s very different from, say, Watchmen or From Hell.

I have a huge soft spot in my heart for Big Numbers. It seemed so good at what it was trying to do, and what it was trying to do seemed so ambitious. Flat out the best art ever on an Alan Moore project, and writing that easily kept me interested despite being (at least on the surface) a subject I had no interest in.

Whatever happened to that era of comics? Big Numbers, Violent Cases, Signal to Noise… interesting, very well-done non-genre books with big name talent on them. At the time, I’d have told you they were an important piece of the future of comics, but I can’t even remember when I last bought a book like that…

Well, SienkieBITCH sucks. First he said he would like to call Alan Moore and finally finish Big Numbers and then, one year later, he decided to replace the late Joe Kubert on Before Watchmen: Nite Owl II. Maybe he did really want to work on an Alan Moore related project. Way to go, Boleslav!

I may be the only person who is glad Moore — writing during the most pretentious phase of his post-‘Watchmen’- superhero-renouncing period — *didn’t* finish this. Every single character is a shrill stereotype: thuggish cops, imbecilic Americans, chirpy taxi drivers. If this is ‘Altmanesque’, then it’s the Altman of ‘Pret-a-Porter’, not ‘Nashville’.

Oliver – “Every character is a shrill stereotype” might be the most wrongheaded review of this book I’ve heard. What about the taxi driver made him “quirky” in your eyes? The bit where he says he’s on pills because of his big accident? You didn’t read it properly.

This article bothers me a bit.

“Clearly, the circumstances surrounding the aborted Big Numbers series are more interesting than the actual comic itself.”

No. The comic is AMAZING. Unfinished or not. Please, I encourage anyone who comes across this to give it a close reading. It’s up online. Don’t skim-read it- set an hour and a half aside to read an issue a day. There’s three, so… that’s like reading Watchmen but stopping just after Dr. Manhattan has left for Mars. It’s enough to feel transported, even if your journey comes to an abrupt halt. This article gives no mention to the fascinating and incredibly believable cast of characters in this book – Christine Gathercole, her sister Jan, her mum Audrey, her father who invites the vicar around to call him an “ugly bastud”, Mr World, Mr. Killingback, Kevin Sorry, Monica Beard…

The art style might make you think you’re in for something somewhat obtuse and unrewarding, but it’s extremely accessible, so long as you’re prepared to put the work in.

“Gone are the cinematic transitions between scenes. Gone are the layered, almost multi-media narrative elements like diary entries or fake excerpts from real-sounding books. Gone are clear semiotic indicators of characterization.”

I honestly don’t think the author read Big Numbers properly because all of this is present in the three available issues online- including, yes, the fake excerpts from real-sounding books. We hear from Gathercole’s previous book Humaness, from her new book “The New Electric Heart”, and from her spoken word record “Housewives’ Choice”. We also drift in and out of dream sequences, memories, play sessions with a model train set, a role-playing game that three of the characters are playing… as for “semiotic indicators of characterization”, if you can’t tell that Mr. Killingback is otherworldy, Christine is heroic, and Hilary Wordsworth is snooty just by looking, then you aren’t looking.

“Instead, Moore and Sienkiewicz give us dozens of characters, living in the same airspace and likely overlapping around this business of the new mall coming to town, and that’s it.”

…I don’t know what to say except read it again, dude.

I grew up not far from where this book is set, and it captures the atmosphere and people of the world I grew up in with pinpoint accuracy. It’s heartbreaking, because having read three issues I’m confident that it could have been one of the greatest graphic novels of all time.