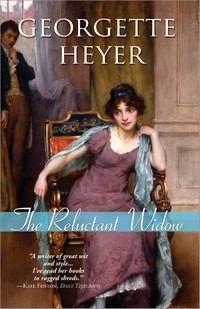

When a wealthy, good looking baron asks you to marry his dissolute and drunken cousin so that you, not he, can inherit the cousin’s crumbling estate, you have a couple of options: you can wish that you were dancing at Almack’s, or you can find yourself accepting the offer, and marrying a man you have never met before in your life, just hours before his death, turning you into The Reluctant Widow.

If you are thinking all this sounds just slightly improbable, I’m with you, but Lord Carlyon, the baron in question, is a very persuasive sort of person; Elinor Rochwood extremely impoverished after her father’s suicide, and desperate to leave her job as a governess; and Eustace Cheviot, the drunken cousin, the sort of really awful person that she really didn’t want to know well anyway. So after Carlyon’s young brother Nicky shows up announcing that he has more or less killed Eustace Cheviot, mostly accidentally, Elinor, without quite knowing how, finds herself a widowand the owner of the crumbling estate Highnoons. (No, really.) She also finds herself beset with aristocratic housebreakers, rusted suits of armor, relatives, her old governess Miss Beccles (summoned to provide a respectable companion). Also, an adorable dog named Bouncer, who takes his duties of guardianship, and his need to find ham bones, very seriously.

By the time she sat down to write The Reluctant Widow, Georgette Heyer was well aware that her financial and popular success rested in comedies of manners like Friday’s Child, with its careful recreation of a world that never was. Still, she resisted creating a second similar romp, instead choosing to write an affectionate parody of the Gothic novel, yielding to popular demand only to the extent of setting this novel, as well, in the Regency period. Like her predecessor Jane Austen, Heyer could not resist making fun of gloomy old homes with secret stairs, rusting suits of armor and lots of hanging vines, but unlike Austen, Heyer chose to insert an actual physical threat in her novel: Bonapartist agents.

The subject of Fifth Columnists had been much in British news during and after World War II, as the threat of Communism replaced the threat of Nazi Germany, and questions continued to arise about the role played by some British aristocrats, some of whom were known to have Nazi or Communist inclinations, in the years leading up to World War II. Heyer was not part of the Cliveden set or friends with Diana Mitford, but she had acquaintances who were, and was well aware of the varying set of reactions to finding out that social acquaintances and even relatives had suspected ties to enemy nations.

That awareness penetrates the novel, as shortly after Elinor’s marriage and Eustace Cheviot’s death, the Cheviots and Carlyons realize, to their mutual horror, that Eustace Cheviot was not merely a bad man, despised by all in the neighborhood, but was passing on information to French agents for financial gain. Almost immediately, they realize that Cheviot could not have acted alone—he lacked both the contacts and the skills—which means that someone they know is a Bonapartist agent. Someone who is fully accepted in the highest social circles.

Of their three suspects, one, Louis de Chartres, is the son of a French marquis, who can, as a horrified Nicky points out, be met anywhere, by which he means anywhere in society. (“Very true,” replies Carlyon. “Mrs. Cheviot seems even to have met him here.”) The second, Lord Bedlington, is an intimate of the Prince Regent (this allows Heyer to get off several good cracks at the Regent’s expense). The third is his son, Francis Cheviot, who is of good ton and dresses exquisitely well. Readers of Heyer’s mysteries, especially Behold, Here’s Murder and Why Shoot a Butler, will probably not be particularly surprised by the denouement (the clothing is a giveaway), but the mystery does at least serve to puzzle most of the characters for some time.

The Reluctant Widow touches on another new concern of Heyer’s, which had appeared for the first time in Penhallow: that of agricultural mismanagement and waste. What with all of the gambling, fighting, womanizing, and delivering secret papers to Bonapartist agents, Eustace Cheviot has understandably not had a lot of time to spend managing his estate or keeping his house in order. This in turn makes the estate considerably less valuable. It soon becomes clear that one reason Carlyon does not want to inherit it is the increased workload the estate will bring him. Not that this keeps him from having to do various things to get the estate in order, when, that is, he is not investigating Bonapartist agents. The mismanagement has also increased the local hatred for Eustace Cheviot, since this has meant decreased employment opportunities. It hasn’t done much for Eustace, either: his failure to manage his lands and rents properly means that his income from them has dropped precipitously, which in turn has made him more desperate for money, which in turn has led to his gambling and spying activities. It’s almost, but not quite, an explanation for just why some of the British aristocracy supported facism—failing mostly because many of these aristocrats were hardly facing the same dire financial issues.

It’s not entirely Eustace’s fault. The Reluctant Widow also deals with the serious issue of the problems that can inflict land (and houses) inherited by minors. Eustace is unable to take control of his lands until he is of age, and although his managers are not accused of mismanaging the property, it is not their land, and they do not have a personal interest in it. When Eustace does come of age, he is already wild and vicious, angry and resentful that he has been left in the care of a cousin not much older than he is, and convinced that his lack of money is thanks to his cousin’s failures. It isn’t, but to be fair, with an estate and siblings of his own, Carlyon’s attention has been scattered. He, on the other hand, inherited his estate shortly before coming of age, giving him immediate control and interest in his lands. They are well managed.

Grand English country houses had survived until World War II, but the issue of these inherited estates would become more contentious in a nation facing major military bills, especially since some of their owners—like Eustace Cheviot—were suspected of having certain sympathies for the other side. (These suspicions were not silenced by statements taken as still supportive of fascism by such people as Diana Mitford and the Duke of Windsor, even if neither continued to live in Britain.)

Society, as Heyer recognized, was rapidly changing, as were the estate homes. Well managed estates could survive as tourist attractions and even as private homes, or private homes and tourist attractions (as, for instance, at Chatsworth, where the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire worked to make the estate and home profitable). Such survival, however, was usually possible only for families and landowners who took an active interest in these estates. Heyer, who had seen estates struggle before this, and who believed strongly in the English aristocratic system, even while noting its flaws, noted the pressure on estates with distress, and continued to explore these issues in her fiction.

A related note of austerity and savings appears in a short scene where Miss Beccles and Elinor find several useful items that only need to be mended to be used; Miss Beccles later rescues several items from the fire, pointing out that they are still useful. Both ladies express their horror that things were simply tossed into the attic rather than repaired, and that now, things that could be useful in a house not exactly flush with cash are getting burned. Heyer had complained about the prices of luxury items and regular food in Faro’s Daughter and fantasized about abundance in Friday’s Child, but here, she reflects wartime austerities where nothing that could conceivably be used would be thrown away.

She also took a fairly critical look at the Gothic romance novel, again undergoing one of its many revivals in part thanks to the recent success of Rebecca and its movie adaptations. Heyer, here and elsewhere, was essentially far too realistic to believe in most of the Gothic trappings, but she could and did have fun with the idea of the creepy, haunted looking house (complete with rusting suits of armor), secret staircases, and dissipated men, even if she could not quite bring herself to turn the cook/housekeeper into a Mrs. Danvers, although many of Heyer’s housekeepers owed more than a touch of their inspiration to Mrs. Fairfax.

Two more quick notes: we’ve talked before in the comments and previous posts about Heyer’s admiration for rude people, and her tendency to present rude people as somehow more effective than those who cling to manners. The Reluctant Widow is an outlier here: the single rude character is an unquestioned villain of the piece (indeed, a flaw of the book is that really he has too many flaws to be believable). Almost all of the other characters are polite indeed, and quite, quite considerate. Indeed, the more considerate and polite the character, the more dangerous.

Second, this is yet another novel where Heyer explores the role of a penniless woman, who needs rescue from the drudgery of employment. Elinor does not need rescue in the same way that Hero does, and she appears to be competent at her job. But the very fact that she agrees to her extraordinary marriage speaks volumes to how much she hates it. Exploring the restrictions placed on women of low income would be a continued subplot of Heyer’s Regency novels, a decided change from her earlier habits of endowing her heroines with wealth, or at least independence, and perhaps a reflection of the economic scarcities of the post World War II period.

The Reluctant Widow has its flaws, and many of them. The first few chapters stretch credibility, even in terms of some of Heyer’s not particularly credible novels. No matter how many times I read it, I cannot bring myself to believe that any woman with the character and morals Elinor is later described as having would marry a man she has never met before even if he is dying, simply to save a complete stranger from potential scandal. Especially since the rest of the book suggests that the scandal would be limited, not completely credited, and in any case not the biggest of the scandals. I can believe even less that Eustace, said to distrust everything Carlyon does, would agree to marry any woman brought to him by Carlyon. Or that Eustace’s relatives, determined to remove Carlyon from the scene (ostensibly out of concerns that Carlyon just wanted the estate, mostly to find the missing memorandum) would not severely question the unquestionably unconsummated marriage. And the less said about the romance between Elinor and Carlyon, hands down one of the least convincing of any of the Heyer novels, the better. (In retrospect I apologize for saying that I had problems believing the romance in Faro’s Daughter—at least those two had a love of quarreling in common.)

Against all this is the bright and amusing dialogue, the hilarious bit with the suit of armor which serves as a caution for any of us planning on defending our homes from invading aristocrats, Nicky’s ongoing cheerfulness, the urbane insults of Francis Cheviot, and Bouncer, that cheerful dog, making this a thoroughly enjoyable, if not thoroughly convincing, read.

Always in need of money, Georgette Heyer sold the film rights to The Reluctant Widow. The film appeared in 1950 and pretty much sank immediately into obscurity, until some YouTube user somewhat rescued it, putting most of a terrible copy with Greek subtitles up on the web. Having now seen most of it, I can completely understand why no one has rushed to get this out to the American public on DVD, and although the last ten minutes are missing from YouTube, or, rather, the last ten minutes appear to be hosted on a malware site, I don’t feel that I was missing much.

Heyer objected to virtually everything in the film, including the many unnecessary changes to the plot (she is correct), elimination of most of her dialogue (ditto, although I have to admit I laughed at the “I write all my best sonnets in bed”) and the addition of a sex scene where—gasp! a bosom is stroked. I didn’t object so much to the sex scene as that it makes absolutely no sense: first the sulky Elinor is pushing Francis Cheviot away (I know!) and then, as Carlyon enters the room, she suddenly kisses Francis (I know!) even though by this point she’s married to Carlyon (don’t ask; I thought it was a dream sequence) and then Carlyon starts to seduce her and says first he married her to his cousin, and then to himself (so it wasn’t a dream sequence) but he hasn’t told her that he loves loves loves her and they kiss and then he says he has to go tie up Francis in his bedroom (!) so they won’t be disturbed (!) at which point Elinor who until now was making out with him panics and hides in the secret passage so Carlyon sleeps on her bed (clothed). He finds her in the morning (I’m lost too), takes tea from the maid and then starts seducing Elinor again who this time seems happier (tea is very seductive) and goes for it even though hours earlier she was HIDING IN A SECRET PASSAGE to escape his MAD CARESSES and fade to black, all while THEY ARE THREATENED BY NAPOLEONIC SPIES. It’s actually worse than this, because I am leaving out all of the stuff in the beginning that makes no sense, if quite raunchy for a 1950s film, but you can hardly blame Heyer for objecting, and making no attempt to have her books filmed again.

Mari Ness usually gets very angsty when people refuse to transfer old movies to DVD or streaming format. Not this time. She lives in central Florida.

Another great review of one of my favourite, but often neglected, GH novels! I agree, the movie is little more than “based on”, and as so often the film makers cut the sexy snarky banter and put in more ‘action’. Pity.

Note also how subtly Heyer indicates Francis Cheviot’s camp manner (and probably also his homosexuality). And yes, Francis is a villain, but he is not a weakling, and I don’t read his character as homophobic at all. In the end, [SPOILER!] Carlyon and he agree, and it’s all for the best.

@@@@@ Nina Lewis: This is one of my favorite Heyers, too, but I don’t think Francis is a villain.

I agree the opening isn’t the most plausible, but I love it: the nighttime arrival, the initial speaking-at-cross-purposes (which is something I don’t normally like) where Elinor thinks Carlyon is the husband of the woman who hired her in London, Nicky’s eruption into the scene, etc. And I think it is just barely plausible that Elinor would be moved to agree to marry Eustace when Carlyon appeals to her directly for her help, and while he’s concerned about Nicky.

I actually like the romance between Elinor and Carlyon, and I think it’s very deeply rooted through the story. She’s plainly attracted to him at their first meeting, he understands what she finds so awful about her way of life as a governess, and their subsequent conversations have a lot of charm and sparkle. She’s perfectly capable of holding her own with him. And he trusts her with his horses.

While her decision to go along with things at the beginning was a bit hard to believe, I think it just points up how Carlyon ALWAYS gets his way. Nobody can say no to him (or if they do say no, it’s because that’s exactly what he was after). I rather enjoyed it, although it gave me whiplash reading it right after Friday’s Child and there was a pretty slow section in the middle. While the romance was not really played up, it was inevitable from early on.

Did it seem odd to anyone else that Elinor wouldn’t go to her husband’s funeral? Were funerals men-only affairs, or what was going on there?

Although I only know about this from reading historical fiction…

Yes, funerals were for men only. It was not considered proper for women or girls to attend. (Even immediate family).

I enjoyed this one, though I find Carlyon one of her less sympathetic heroes. His habit of constantly telling Elinor not to concern herself about things when she has perfectly good reasons to worry gets irritating after a while.

I like the character of Francis Cheviot. Where the gay characters in her contemporary mysteries come across as just a collection of stereotypes, Francis has a bit more depth to his character and is one of the more interesting people in the book.

A related note of austerity and savings unfortunately didn’t apply to Heyer herself. I believe this is the book that caused a worldwide shortage of exclamation points!

Long time follower, first time poster. Also, long time Georgette Heyer reader.

This is not one of my favorite GH books. I had a hard time getting through the middle chapters on my re-read. Bad habit, to skip to the end, but I had already read the book at least once before, so it wasn’t like I didn’t know how it ended. Elinor is an OK heroine, but I find Carlyon to be boring as the hero.

I’m sorry, but I’m going to be the nit-picker this time. English major, can’t help myself. It’s Elinor Rochdale. Her family name is mentioned quite often, the Rochdales of Feldenhall. And, sorry, Behold, Here’s Poison, one of my favorite of the mysteries, if not yours.

@Nina Lewis — Not to be overly spoilery, but is Francis really the villain here? The characters don’t like him, and yes, he commits more than one highly questionable act, but he’s doing so for reasons that I think Heyer mostly approves of. The really unquestioned terrible person is Eustace who even apart from everything else sold out his country. I feel that Elinor has to marry Carlyon just to get her name changed again.

The movie had no witty banter but that was just one of the problems.

@etv13 — I usually love talking at cross purposes, and this was an amusing conversation – but the problem is that the initial setup is just so implausible I couldn’t really buy it.

You have a point about Elinor and Carlyon immediately understanding each other, but I still think the romance is weak. (If better than the “romance” in the movie.)

@SPC – I checked what few primary sources I had on hand. Princess Caroline did not attend the funeral of her daughter Princess Charlotte in 1817, but Caroline was in Italy at the time. Mary Shelley did not attend the last rites for Percy Bysshe Shelley in 1822, but she was by all accounts very distraught and may not have been up to it. Lord Byron told his mistress Claire Clairmont not to attend the burial of their illegitimate child, but that may have been to prevent further scandal. When Mrs. Churchill dies in Emma they have a funeral but it’s not clear who attends it other than her husband and Frank. Which may not mean as much as it sounds since the funeral takes place in Yorkshire–an expensive journey. I’ll keep checking.

@Azara — And yet, interestingly enough, Heyer was to give us one of her worst gay characters in Duplicate Death a few years later — and that character unlike Francis (who is somewhat sexually ambigious, like Aubrey in Penhallow) is unquestionably gay. Grr.

@Pam Adams — Well, she was writing escapism, not austerity!

@Azurite — I’m a former English major myself, so I understand the nit-picking need.

@MariCats: I think the romances in a lot of Heyers could be characterized as “weak,” or at least as being sort of deeply underground. Sprig Muslin, for example, and The Foundling (which is nonetheless one of my favorite Heyers), and The Grand Sophy all end in match-ups that have me saying, “Oh, well, okay, I guess.” Elinor and Carlyon at least spend a fair amount of time together, and they feel well-matched to me. (Not that I’m suggesting that Gilly and Harriet aren’t well-matched, just that their relationship isn’t really what the book is about at all.)

Thanks for watching the film – I found the first section on youtube and it was so grating I was reluctant to continue. From what you say, it got a lot worse after the little I saw. It’s a pity it was so bad – I think quite a few of her books would make very good films or tv series. Her plotting was mostly a lot tighter than some modern period pieces.

I think that visual media could also deal very well with the feature etv13 mentions, where the romance is to a certain degree underground. Sympathetic acting could bring the attraction forward, without having to alter Heyer’s dialogue at all.

I like the book – Miss Beccles, Bouncer and Nicky, and especially Highnoons make up for the less-than-charming “masterful” Carlyon.

I notice that I have a weakness for Heyer dogs, Heyer governesses (with affectionate nicknames) and most of all Heyer houses. My most beloved Heyer is the story of Fontley – the house is such a strong character that it plays a nearly active role in the story, and how the human characters relate to Fontley reveals their characters most clearly and strongly.

Highnoons is not cherished and loved like Fontley, and it is discarded at the end of the book, but I loved its atmosphere. Heyer herself was not the housewifely type, according to the biographies, but she had the knack of describing housewifely concerns nicely. I love Miss Beccles’ enthusiasm for laundry lists. And I’m always sorry when Elinor tears up the carefully darned linen to bind Nicky’s wounds ;-)

I read Reluctant Widow as young adult – which means I didn’t swallow the improbable parts as easily as in the Heyers I read as teenager. But I find Elinor’s change of circumstances and her desperate wit entertaining and satisfying reading. In spite of Eustace’s grisly death.

I love your reviews!!!

Coming late but had to add – women did not go to funerals. Serena doesn’t go to her father’s. Cranford ladies don’t go either.

I’ve seen the movie – late night on TV pre VCR days and it is beyond awful.

Don’t be sorry for missing the last 10 minutes – they were actually worse than the rest of the movie.