Welcome back to the British Genre Fiction Focus, Tor.com’s regular round-up of book news from the United Kingdom’s thriving speculative fiction industry.

This week, we begin with a discussion of self-publishing, prompted by an article in The Guardian asking why the form is still scorned by literary awards—an article which was itself prompted, presumably, by the news that Sergio de la Pava’s novel A Naked Singularity has won a major prize, despite being self-published fully five years previously.

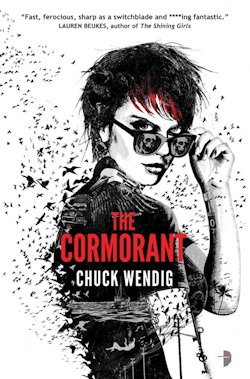

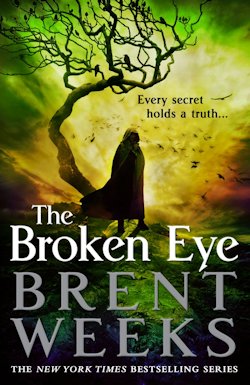

Then, in a bumper edition of Cover Art Corner, the third time’s the charm for two recently revealed new books—The Cormorant by Chuck Wendig and The Broken Eye by Brent Weeks—both of which mark the third volumes of their respective series.

And finally, The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, the Unbeliever begins again… at the very moment it ends.

No Prizes for Self-Publishing

In an article for The Guardian last Friday, Liz Bury asked why self-publishing is, despite the immense success of several of its most visible figures, still scorned by literary awards.

A self-published book reaching the top of the charts is losing its power to surprise. Certainly it’s less shocking than it might have been a few years ago to learn that Violet Duke’s self-published romance novels, Falling for the Good Guy and Choosing the Right Man nabbed two spots on this week’s iBookstore bestseller chart, alongside the likes of JK Rowling and Dan Brown.

It’s safer for an editor at a mainstream publishing house to buy a book that reads a lot like last year’s bestseller, than to stick out their neck in support of an unproven concept that might not deliver. But readers have no such reason to be cautious, so buyer power is increasingly setting the agenda in mass-market publishing.

New digital bestseller lists, such as the Kindle and iBookstore charts, are helping self-published authors be seen. And then there’s EL James, whose stuff-of-dreams rise from self-published writer of fan fiction to multimillionaire bestselling author earned her pole position on Forbes’ list of the year’s highest-earning authors.

My first problem with Bury’s brief piece is with her premise, because commercial success has never necessitated critical acclaim or literary praise. Case in point: it didn’t matter a damn how many millions of copies of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone were sold, JK Rowling still wasn’t going to be nominated for a literary prize like the Booker.

Moving beyond Bury’s preamble, her point about Sergio de la Pava is more powerful. Just last week, de la Pava picked up the PEN/Robert W. Bingham award for his novel A Naked Singularity. Thing of it is, A Naked Singularity was self-published way back in 2008, and only now noticed because it was picked up by a “proper” publisher.

Problematic, perhaps, but I sympathise with the circumstances leading to this so-called snubbing. I’m far from the world’s most popular blogger—heck, I’m not even Scotland’s—yet on a daily basis I can expect a veritable plague of pitches and offers of review copies from authors who’ve self-published their novels. Now I couldn’t feasibly read a fraction of these, even if I was to swear off books released by the industry’s bigger imprints entirely, and of the few that I have taken a chance on, the vast majority have been… well, let’s not beat around the bush here: they’ve been utter rubbish.

I’m certainly not saying that self-published fiction can’t be brilliant. Of course it can. There’s just so much of it that it’s practically impossible to pick the good books from the bad.

So inasmuch as self-publishing does indeed open the door to some interesting stuff—here Bury and I agree completely—it also removes the barrier for entry that being published “properly” represents. Thus, a lot of crud is self-published. With fiction published through traditional models, there is at least a reasonable presumption of quality. So it’s hardly a surprise that “most literary awards are closed to self-published books,” as Bury illustrates, albeit basically:

Entry criteria for the Booker prize state that “self-published books are not eligible where the author is the publisher or where a company has been specifically set up to publish that book”, while the Bailey’s women’s prize for fiction stipulates that books must come from a “bone fide imprint.”

As more authors choose to go it alone, literary prize administrators will soon be playing catch-up.

Will they, though? From my perspective, this seems a stretch. The administrators of literary awards along the lines of the Booker and the Bailey’s (the women’s prize for fiction formerly sponsored by Orange) have long taken what we’ll kindly call a choosy view of the full field, dismissing entire genres—did someone just whisper science fiction?—on the basis that genre fiction simply isn’t literary.

And though it is neither right nor reasonable to call self-published novels a genre, they are often seen as such, and in many cases dismissed on this basis. I can’t see that changing until there’s a better way to separate the wheat from the chaff. And I can’t imagine what that is. Marketing isn’t the answer. A new breed of media, maybe, wholly devoted to self-publishing. Or some sort of optional certification that a book is at the very least readable.

Thoughts from the peanut gallery, please?

An interesting wrinkle: as raised in the comments section of The Guardian article, the Folio Prize for Fiction actually is accepting self-published submissions. That being said, the publisher of any novel which makes the shortlist will have to cough up £5000 for publicity as part of the bargain: a big ask for a small self-publisher apt to majorly curtail the ultimate number of such submissions.

Cover Art Corner: The Broken Eye of Miriam Black

Two big ones for you today. In no particular order, let’s kick off with The Cormorant: the third volume of the Miriam Black books by Chuck Wendig, who—alongside Daniel Abraham—must be one of contemporary genre fiction’s most industrious authors.

Truth be told, I haven’t read as many of Wendig’s novels as I’ve intended to, but Blackbirds was just wonderfully wicked, and I have until the end of December to get busy with Mockingbird. Fingers crossed I can find a few moments, because The Cormorant sounds like fantastic fun:

Miriam is on the road again, having transitioned from “thief” to “killer.”

Hired by a wealthy businessman, she heads down to Florida to practice the one thing she’s good at, but in her vision she sees him die by another’s hand and on the wall written in blood is a message just for Miriam. She’s expected…

Here’s a guessing game that could be fun to play: assuming this isn’t the last we see of Miriam Black, let’s put our two pence in as to the name of the next novel. It’s got to be a bird, and have an open secret meaning. So how about… The Black Grouse?

The Cormorant’s cover art is by Joey Hi-Fi, by the by. Predictably, it’s brilliant.

In a curious coincidence, I’m in pretty much the same place with Brent Week’s Lightbringer series as I am the Miriam Black books: I read The Black Prism when it was released and quite liked it. I very much meant to make time for The Blinding Knife, especially given its better reception, but here we are, nearly a year on from said sequel, and I’m still a book behind. Too busy putting together this column every week, clearly!

In any event, though I don’t believe a blurb has been released for The Broken Eye quite yet, last week Orbit revealed the cover art of book three of the now four-volume long Lightbringer Trilogy.

Gorgeous, isn’t it?

Which just goes to show that there’s really no problem with hooded dudes on our book covers… so long as they’re not the sole focus. Simply pose them these needful evils to something infinitely more interesting—like a pretty tree in this instance, or the Ravenheart Award-nominated staircase emblazoned upon The Blinding Knife—and it’s perfectly possible for the covers they’re on to be awesome.

Kudos to artist Silas Manhood for both illustrations. Oh, how I wish my hardcover copy of The Black Prism had his art instead of a picture of a random moustachioed man…

The Last Dark At Last

Finally for today—appropriately so, I might moot—Gollancz confirmed last week that The Last Dark will be published on the 17th of October. The Last Dark is of course the last part of The Last Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, the Unbeliever by Stephen R. Donaldson.

Compelled step by step to actions whose consequences they could neither see nor prevent, Thomas Covenant and Linden Avery have fought for what they love in the magical reality known only as ’the Land’. Now they face their final crisis. Reunited after their separate struggles, they discover in each other their true power – and yet they cannot imagine how to stop the Worm of the World’s End from unmaking Time. Nevertheless they must resist the ruin of all things, giving their last strength in the service of the world’s continuance.

This series—the third to feature the titular Unbeliever—began in 2004 with The Runes of the Earth, but the overarching narrative originated, incredibly, in 1977, with the first book of The First Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, the Unbeliever, namely Lord Foul’s Bane. Which means that readers who have been following the story from the start have spent nearly forty years with this character.

No surprise, then, that folks like Shawn Speakman, editor of the excellent epic fantasy anthology Unfettered, give The Last Dark great weight:

While reading The Sword of Shannara by Terry Brooks has had the largest impact on my overall life—after all, working with Terry has opened numerous doors that I otherwise would not have been able to walk through—no series of books have influenced me more than The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, the Unbeliever by Stephen R. Donaldson.

I know. Those are serious words. Say what you will about Donaldson. He doesn’t shy away from doing the unbelievable. He doesn’t work hard at making the reader comfortable. He does quite the opposite, in fact. From the moment Covenant did the most horrible of acts on a girl in Lord Foul’s Bane, I knew Donaldson would polarize people. They would either love the series for the beauty of the Land and its characters or earnestly hate it for that one act.

I’ll be the first to confess that I haven’t read any of the Unbeliever books. That said, I really rather want to know what that “one act” is, now. One wonders whether it would be as shocking today as it once was…

Well, if I really fancy finding out, it’ll be much easier after the release of The Last Dark than it is at the moment. Why? Because of the other part of Gollancz’s announcement: that they’ll be making the entire saga—except, so far as I can see, the novella Gilden-Fire—available digitally for the first time ever, day and date with the publication of its conclusion.

Evidently, every end begets a beginning…

Which is such a fitting way to close out the column for today that I simply can’t resist! See you all again next Wednesday, then, for another edition of the British Genre Fiction Focus.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. On occasion he’s been seen to tweet, twoo.

I can think of one self-published novelette which has been shortlisted for a Hugo this year, and a self-published novella which won the BSFA Award back in April and is a finalist for the Sidewise Award…

Donaldson: Yup. Still shocking. It ‘helps’ (in a manner of speaking) that Donaldson is an astounding writer, so his ‘one act’ is more… emotive? Persuasive? Awful? (What’s the right word?)… than the many grimdarkorcs that have followed. The man has made a career out of writing self-loathing protagonists doing horrible things across various genres. Which isn’t meant to sound dismissive: he’s one hell of a writer.

Awards: This is an interesting controversy. Most awards don’t take ebooks – for a few reasons. If they’re juried, for example, not all the judges have e-readers. Or sometimes it is intentional: not taking “ebooks” as a way of warding off the self-publishing floods.

That said: The Kitschies now ebook-only submissions and have always been open to self-published books. If it helps counteract other awards’ fears: we’ve never had a tsunami of “utter rubbish”. (Much the reverse. And, in fairness, self-published authors are generally much better about following the submissions instructions!)

I think the Clarke Award has made noises as well about ebooks and self-published books, I’ll see if I can summon the mysterious Tom Hunter to reply.

And, technically, there’s no reason a self-published book couldn’t win any of the other major SF awards either – Hugo, Nebula, BSFA, DGLA, BFS, Tiptree or World Fantasy Award, that I know of, have no barriers to self-published books.

I think that the tipping point has come with authors like Jeff Noon. I can understand (but not agree with) a reactionary fear when it comes to keeping new ‘unknown’ (if huge-selling) authors out of the picture. However, when authors that are prior award-winners, ones that command huge amounts of respect, are excluded, even the most conservative award has to start questioning its own policies.

Outside of SF/F – The Ian Fleming Dagger for the CWA is also moving to an ebook only format, which should make a difference as well.

@niall: Self-publishing shouldn’t be a problem: authors from Jane Austen to Virginia Woolf have arguably self-published. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was self-published. Equally, Sturgeon’s maxim applies to all forms of publishing, traditional and otherwise. It’s self-editing that matters. Do you think that some kind of peer-review system could be established or that some kind of accessible basic writing guides could be released for new authors? Another one: writer’s workshops. Could a free-or-low-cost workshop be held online?

Yes. Must have more Miriam Black in my library.

Gilden Fire is merely an excerpted chunk from the first trilogy, it’s pretty but not earth-shattering or a major piece of plot.

I was fascinated by the first trilogy, adored book 4 for its turning the world on its head, but books 5 and 6 didn’t hold up, and book 7 didn’t thrill at all. I might grab a used copy of 8 and 9, but there’s no rush to read them.

From the moment Covenant did the most horrible of acts on a girl in Lord Foul’s Bane, I knew Donaldson would polarize people. They would either love the series for the beauty of the Land and its characters or earnestly hate it for that one act.

It wasn’t only that, but it was that I didn’t like a character who so patently wanted to disbelieve the world he was in, I couldn’t stand it.

Donaldson’s mysteries are probably my favourites of his word – the Mick Axbrewder / Ginny Fistoulari novels. They’re still hard-boiled, self-loathing protagonists that do awful things and think *way* too much about everything. BUT, they’re good stories and, unlike much of Donaldson’s other work, I think they’re ultimately a bit more… redemptive.

This might go down easier from a blog that was more oriented around “literary fiction,” but to see it coming from an SF publisher’s blog is quite distressing.

Well yes, as long as it’s a traditional press and not a paperback publisher. You know the type. They publish science fiction or romance. They’ll publish anything and 90% of it is crud?

To start, I’d reject the notion that it has anything to do with actual issues rather than prejudice. However, within the paradigm you’re suggesting I can think of several ways: Require a minimum number of copies sold, require books to be nominated from a larger committee of prominent writers or reviewers, require a certain number of reviews in mainstream outlets. All of those have their own problems, but they’re better than a blanket ban.

@Numtini: Spot on. Being a self-publisher who has tried in the past to get mentions here and on similar publisher-devoted sites–and failing every time–it strikes me as easy for them to say “it’s not publishing’s fault for the snubbing you guys get… there’s just so damned many of you. Like roaches.” In other words, hoping they’ll just go away, except for the occasional roach with a cool coloring on its back, or the one that appears on YouTube getting the upper hand on a kitten trying to surprise it. The occasional roach is okay. Some of my best friends are roaches. The rest need to be exterminated ASAP.

I shudder to think of how many books (including my own) will never see the light of day thanks to the daily abuse inflicted by this market upon self-publishers.

This might be an appropriate place to ask this question: Are publisher’s slushpiles shrinking? Do the number of people going the self-publishing route mean there are fewer submitting manuscripts to traditional publishers?

Because I’ve been reading a fair number of self-published books this year, and it sure feels like I’m reading thru slushpile submissions sometimes. It pretty much follows the same bell curve I found editing a couple of short story anthologies back in the 1990’s: A big bunch of “meh” stories in the middle, smaller numbers of actively, obviously bad on one end, and small numbers of pleasing worthwhile surprises on the other end.

The manuscript submission process at traditional publishers acted as a (certainly imperfect) gateway to narrow down the contents of that bell curve. Self-publishing hasn’t come up with a satisfactory way, yet, to replace that gateway. As a reader, I don’t want to spend my reading time reading slush.

(I’m finding that, after about a half year of sampling and reading self-published books, I’m starting to download fewer self-published works and going back to traditional publishers again.)

Adopting the approach used by the Cybils Awards (the YA Bloggers award) would be one method of dealing with the “there’s simply too many” objection to self-published entries. The Cybils has a two stage process. Stage one involves quite a large number of basically first stage readers divided into panels, and all the entries are broken up and allocated across the panels. Each book has to be read (or started) by a certain portion of the allocated panel. Each panel passes up nominations to the stage two judges. The stage two judges read the panel-passed entries, and pick the finalists.

It’s a system which gives every nominated book a chance without unreasonably expecting a handful of people to read hundreds of books.

As for self-publishing and awards – I’ve been a finalist for the Aurealis Awards twice, and to the Cybils once. Recognition is happening in juried awards. It’s less likely to occur in popularity vote awards unless the book happens to be a runaway success.

Andrea K Host

re: the “one act”. Yeah, it’s still pretty out there. Looking back, it’s not so much that it’s there to “shock” the reader – it happens very very early in the first book, so you haven’t even had time to get comfortable enough in the universe to be shocked by anything – it’s that it’s there to establish that the main character is terrible.

“The one act”: as shocking now as then? YES. Possibly more so.

I’m actually one of the few people I know in my RL who have even finished the first book (I have read and own the first two trilogies) because of the utter fury and horror they felt. Most of them refused to read another Donaldson, ever.

Yes, the act is shocking, particularly in the context it occurs. Thomas Covenant is a man taking out his rage at the universe, his frustrations, etc, on the one person who has helped him the most. The rest of the first trilogy can be understood as him trying to undo that one act.

Self-publishing resulting in slush-piles of ill-disciplined self-indulgent authors and the like? I’ve seen and read more of that in publishers’ annual lists that I care to remember. It turned me off reading science fiction and fantasy for about ten years – apart from a few who I’d already discovered such as Doris Lessing and Ursula Le Guin. “Slush piles of ill-disciplined self-indulgent authors” seems to define the romance genre … and military SF, and several other genres I haven’t got the time to bother mentioning.

Covenant is very problematic. It didn’t bother me as a teenager but as an adult it bothers me more and more. SPOILERS: The setup is that Covenant is an embittered writer suffering from leprosy, who finds himself zapped into a magical secondary world. He assumes he’s hallucinating. When magic Earthpower starts to heal his leprosy and he regains some feeling in his extremities, he rapes the woman who finds him, and then spends much of the book rationalising it (none of this is real, he says, and in any case I was overcome by the sudden healing etc.)

You can certainly argue that the book is about his self-loathing and unbelief etc, but I find it pretty poor form that the victim of his rape is really a kind of two-dimensional prop who is only in the book to give him something to agonize about and redeem himself for. Then I read Donaldson’s SF ‘GAP’ series, which is essentially a whole string of rapes and agonizing and more rape, and I gave up on him.

I’ve found Richard Lea’s Guardian article “Why are publishers the new villain in the digital age?” rather enlightening. The remarks by agedpublisher in the comments are also worth a look.

I do not have to like the main character in a book, but Covenant’s whining self-loathing is tedious. The rape is disgusting, his attempts at self-justification simply ludicrous. I’d say don’t bother Niall, because the books are boring unless you have a penchant for misogynist jerks.

I have seven books that I published under my imprint “Airplane Books.” None of these books have won any prizes from any one. I managed to get a 5 minute interview on Channel 14 (Evansville, IN) to promote my books, but that spot did not create many book sales.

I’m not sure that editing is the problem. I’ve had some comments from readers that my books lacked editing, but then I’ve seen books by famous authors such as Steven King, Michael Connelly and many others, that have some of the same grammatical errors as the ones pointed out to me by my readers. So editing isn’t the problem. The problem is publicity and marketing.

As an unknown, self published author, I risk being rejected by 100 out of 100 people who pick up a book in Barnes and Noble. Barnes and Noble will not stock self published books. They don’t need to. Their shelves are full of standard published books.

I’ve submitted to agents and publishers and been rejected by both. No-one is going to buy a Don Yarber mystery when they can buy a Michael Connelly mystery unless some super hype has preceded that purchasing trip.

Lets face it. The deck is stacked against self publishing.

To be honest, as a self-publisher myself (in a completely different genre), I don’t really feel that the deck is stacked against us.

For one thing, there’s only a tiny amount of “traditionally published” books that win any award or even succeed in selling a decent amount of copies. So these complaints of “my book didn’t win any awards or become a best-seller” are a little silly. Millions of books are published every year, so the competition is very very tough.

But there’s even a bigger issue here:

The vast majority of self-published authors don’t know a thing about publishing. Many of them are incredibly gifted writers, but they don’t know the first thing about manufacturing a professional-looking book. Most of them aren’t even aware of the difference between “writing” and “publishing”. So they write a (hopefully) great novel, smack the text on the page and send it to a printer… and then get disappointed when their books flops.

I can tell you right now, that when working on my own book, 90% of the stuff we did had nothing to do with “writing”. There are things like a professional cover design, page layout, endless tweaking of word and paragraph justification, repeated proofreadings by different people, and dozens of other little and big things we needed to do. We’ve actually spent hundreds of men-hours and a couple of thousands of dollars making sure everything is as professional-looking and attractive as it can be.

And guess what? It paid off. We’ve sold hundreds of copies, without any press attention or media campaigns (and we would have sold way more if our marketing skills weren’t so terrible).

So if you’re a budding self-published author, do yourself a favor: take the time and effort to learn the “secrets” of being a good publisher. It’s a completely different skill than being a good writer and it is no less critical to your success. Remember, as indie author, there’s no one else to do this job for you.