Alan Moore likes sex. This makes him something of an anomaly in the world of comic book writers. I’m not saying that other scribes don’t enjoy the pleasures of the flesh in their off hours, but relatively few are interested enough in the erotic as a subject to make it a part of their writing.

Of course, there are all kinds of reasons for this prudishness—not the least of which is industry censorship—but the result is that comic books are largely a sex free zone. To the degree that sex does appear in comics, it mostly takes the form of suggestively drawn female characters. At best, that’s an adolescent way of dealing with sex, and at worst it’s something darker—with the sex drive either implicitly rejected or sublimated into violence.

Alan Moore is the great exception. At least in the world of mainstream comics, he’s the longstanding king of the perverts. In V for Vendetta, for example, his dystopian London is populated by people with a range of sexual appetites, and often in the series, sex has a desperate hue. We first meet the main character, Evey, when she is trying to make some money as a prostitute. A side story follows abused wife Rosemary Almond, who sleeps with a man she hates after her husband is killed, and then later becomes a stripper. Helen Heyer, the wife of chief state spy Conrad Heyer, wields sex like a weapon, manipulating men at every turn—including her cuckolded husband. Bishop Lilliman, the head of the state-sponsored church, is a child molester. And on and on. Even the mysterious V himself is strongly implied to be a gay man who was used as a scientific guinea pig because of his sexual orientation. In the most emotionally effective section of the entire series, Evey reads the tale of Valerie, a former actress who died in the same concentration camp as V because she was a lesbian.

Moore fruitfully explored the limits of sex in mainstream comics in the pages of The Saga of the Swamp Thing during his historic run on the series from 1983 to 1987. He recast the character of Swamp Thing and reconfigured the world the creature occupied, changing him from a man-turned-monster into a mystical creature born of the earth’s essential elemental forces. Later in the series, he took this process a step further—sending Swamp Thing into space, making him a cosmic entity.

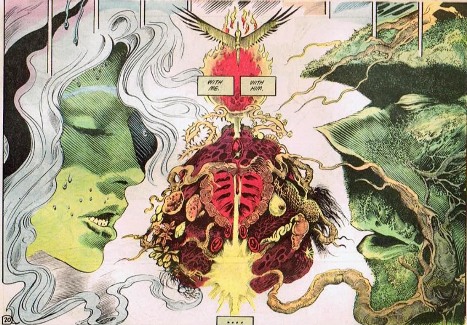

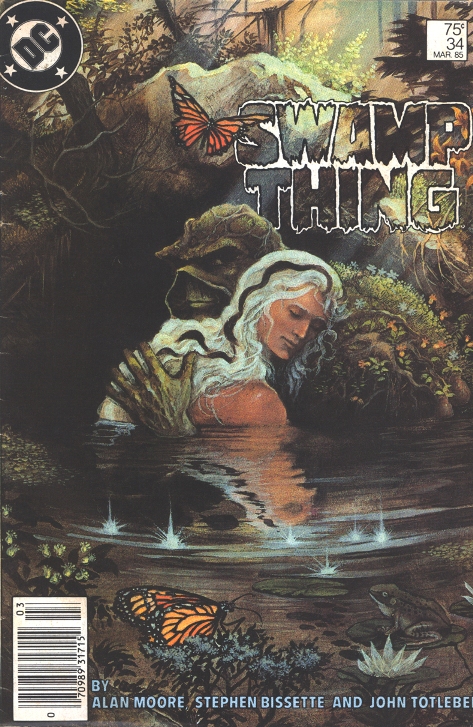

What’s interesting here is that the progression of the Swamp Thing from a backwoods ghoul into a intergalactic traveler is punctuated at every turn not so much by violence (the series, at least under Moore, was never heavy on action) but by eroticism. Swamp Thing’s relationship with Abby Arcane isn’t some subplot, it is the main story of the series. The question of what kind of relationship a woman can have with a giant walking vegetable was answered in spectacular fashion in issue #34, “Rite of Spring.” This issue is one of the most remarkable pieces Moore has ever written. Beautifully drawn by Stephen Bissette and John Totleben, with colors by Tatjana Wood, it is an issue-length communion between the Swamp Thing and Abby—physically, emotionally, and spiritually. When Abby eats a tuber from Swamp Thing’s body, things get trippy and weird—and sexy. More than anything else Moore did on the series, it dramatizes the writer’s theme of the interconnectedness of all living things.

Later in the series, Abby and Swamp Thing are secretly photographed in the process of a naked frolic in the marsh by a sleazy opportunist who sells the pictures to the press. Abby becomes a pariah in the press. Fired from her job and hounded out of town, she flees to Gotham where, almost immediately, she’s arrested on suspicion of being a prostitute. When Swamp Thing gets word of this outrage, he takes on all of Gotham City, including its most famous protector.

Soon after, Swamp Thing is forced to leave earth and begins an Odyssey-like adventure across the galaxy, trying to get home to Abby. On one planet populated entirely by blue vegetation, he creates a mirage from the flora, manipulating it all into the form of his lover. When this blue illusion won’t do, he is hurdled further across the universe, at one point encountering an entire planet, Technis, which tries to take him as a lover. Swamp Thing does indeed help her procreate (conjuring echoes of Odysseus’s sexual enslavement by Calypso, which in some post-Homeric accounts resulted in the birth of sons).

Since Moore left Swamp Thing in 1987, the series has passed through many talented hands. No one ever put quite the emphasis on sex and mysticism as Moore, though. Years after leaving Swamp Thing, Moore’s interest in the erotic resulted in fascinating independent works such as his graphic novel Lost Girls with artist Melinda Gebbie. The book concerns the sexual adventures of three women years after they achieved fame as children (Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz, Alice from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and Wendy from Peter Pan). Moore also wrote a book-length essay, 25,000 Years Of Erotic Freedom, a history of pornography and erotic art. The first line of this tome perfectly captures the playful spirit of the thing: “Whether we speak personally or palaeoanthropologically, it’s fair to say that we humans start out fiddling with ourselves.”

It’s also fair to say that, in all probability, some people will find Moore’s emphasis on sex and its connection to mysticism to be tiresome or inappropriate for the medium of comic books. To that, one could only say that in a field that is shaped and defined largely by violence, its nice to have at least one giant of the field whose interest in bodies giddily encompasses its more creative, and procreative, functions.

Jake Hinkson is the author of the books Hell On Church Street, The Posthumous Man, and Saint Homicide. Read more about him at JakeHinkson.com. He also blogs at The Night Editor.

Is this prudishness just something common to English language comics? Obviously it’s not an issue with Japanese ones. I wonder about comics from other cultures though. I would think there are many that would embrace the topic. One thing I like about the Japanese comics involving eroticism is that so many women write them as well, so we aren’t just seeing a male point of view.

I had honestly never even considered reading The Saga of the Swamp Thing, but it looks quite beautiful. I just bought the first couple of volumes.

Does this apply to the Phantom? I’ve always read it as a conflict between the Phantom’s love for Diana Palmer and his instinct to protect his people against the violence of the European traders and various other threats.

“but relatively few are interested enough in the erotic as a subject to make it a part of their writing!”

this exactly shows, what I think is wrong with ‘comics’ or rather the public view of them: it’s all about Marvel.

French, not to mention Japanese, comics are full of sex. Gratuitious or Meaningful. So, are in fact, a number of English language projects, such as Transmetropolitan, Lucifer, and others…

I am disappointed to see such as cliche re-inforcing and blinkered statement here on TOR.

I do aplauded your approching the topic though. because really it is not about sex, it is about prudisheness and what we see as accetpable and politically correct…

Definitely some interesting insights about Moore here, but I have to join the chorus in pointing out that the definition of “comics” used in this piece is basically “Marvel and DC code-approved floppy comics,” which is excessively limiting.

There’s a long history of sex in the comics: obviously in the undergrounds, in strips like Wally Wood’s Cannon, Heavy Metal magazine and similar outlets, the whole sex-comics ecosystem of the ’90s, more recently in the webcomics explosion, and quite a lot elsewhere, including the non-Code magazines of the late ’60s and early ’70s. And even the Big Two have had substantially more sexual content in recent years than was true in the ’80s — the entire Marvel Max line, for example. (See Tim Pilcher’s two histories/art books Erotic Comics and Erotic Comics 2 for a more in-depth look at the history. )

So saying “comic books are largely a sex free zone” is only true looking at a very specific historical segment of the market, which is begging the question. Alan Moore was notable for writing generally positively about sex at DC in a time and place when that was not common, but it would be more interesting and useful to examine his precursors and influences — I’m not aware that he had much connection to the US underground scene, but there might be some fruitful UK precursors, such as Hunt Emerson.