They say that the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II ordered a group of children to be raised without any human interaction so that he could observe their “natural” behavior, untainted by human culture, and find out the true, deep nature of the human animal.

If you were born around the turn of the 21st century, you’ve probably had to endure someone calling you a “digital native” at least once. At first, this kind of sounds like a good thing to be—raised without the taint of the offline world, and so imbued with a kind of mystic sixth sense about how the Internet should be.

But children aren’t mystic innocents. They’re young people, learning how to be adult people, and they learn how to be adults the way all humans learn: by making mistakes. All humans screw up, but kids have an excuse: they haven’t yet learned the lessons the screw-ups can impart. If you want to double your success rate, you have to triple your failure rate.

The problem with being a “digital native” is that it transforms all of your screw-ups into revealed deep truths about how humans are supposed to use the Internet. So if you make mistakes with your Internet privacy, not only do the companies who set the stage for those mistakes (and profited from them) get off Scot-free, but everyone else who raises privacy concerns is dismissed out of hand. After all, if the “digital natives” supposedly don’t care about their privacy, then anyone who does is a laughable, dinosauric idiot, who isn’t Down With the Kids.

“Privacy” doesn’t mean that no one in the world knows about your business. It means that you get to choose who knows about your business.

Anyone who pays attention will see that kids do, in fact, care a whole lot about their privacy. They don’t want their parents to know what they’re saying to their friends. They don’t want their friends to see how they relate to their parents. They don’t want their teachers to know what they think of them. They don’t want their enemies to know about their fears and anxieties.

This isn’t what we hear from people who want to invade kids’ privacy though. Facebook is a company whose business model is based on the idea that if they spy on you enough and trick you into revealing enough about your life, they can sell you stuff through targeted ads. When they get called on this, they explain that because kids end up revealing so much about their personal lives on Facebook, it must be OK, because digital natives know how the Internet is supposed to be used. And when kids get a little older and start to regret their Facebook disclosures, they are told that they, too, just don’t understand what it means to be a digital native, because they’ve grown up and lost touch with the Internet’s true spirit.

In “It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens,” a researcher named danah boyd summarizes more than a decade of work studying the way young people use networks, and uncovers a persistent and even desperate drive for online privacy from teens. For example, some of the teens that boyd interviewed actually resign from Facebook every time they step away from their computers. If you resign from Facebook, you have six weeks to change your mind and reactivate your account, but while you’re resigned, no one can see your profile or any of your timeline. These kids sign back into Facebook every time they get back in front of their computers, but they ensure that no one can interact with their digital selves unless they’re there to respond, pulling down information if it starts to make trouble for them.

That’s pretty amazing. It tells you two things: one, that kids will go to incredible lengths to protect their privacy; and two, that Facebook makes it incredibly hard to do anything to protect your privacy.

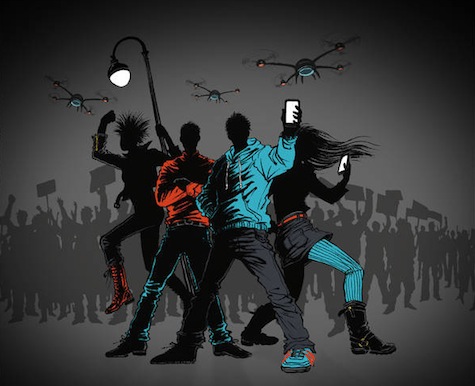

You’ve probably heard a bunch of news about Edward Snowden and the NSA. Last June, Edward Snowden, an American spy, fled to Hong Kong and handed a group of American journalists internal documents from the NSA. These documents describe an almost unthinkably vast—and absolutely illegal—system of Internet surveillance from American spy agencies. They are literally picking countries out of a hat and recording every single cellphone call placed in that country, just to see if it works and can be scaled up to other countries. They’re literally tapping into the full stream of data running between Google and Yahoos’ data-centers, capturing clickstreams, emails, IMs, and other stuff that’s not anyone’s business for billions of innocent people, including hundreds of millions of Americans.

This changed the debate on privacy. All of a sudden, normal people, who don’t think much about privacy, started to think about privacy. And they started to think about Facebook, and the fact that the NSA had been harvesting huge amounts of data from Facebook. Facebook had collected it and tied it up with a bow where any spy could grab it. It was something that people in other parts of the world were already thinking about. In Syria, Egypt, and elsewhere, rebels and government enforcers have conducted road-stops where you are forced to log into your Facebook account so they can see who your friends are. If you’re friends with the wrong person, you’re shot, or jailed, or disappeared.

It got so bad that Mark Zuckerberg—who’d been telling everyone that privacy was dead even as he spend $30 million to buy the four homes on either side of his house so that no one could find out what he did at home—wrote an open letter to the US Government telling them they’d “blown it.” How had they blown it? They’d gotten people to suddenly notice that all their private data was being sucked out of their computers and into Facebook’s.

Kids intuitively know what privacy is worth, but being kids, they get some of the details wrong. It takes a long time to learn how to do privacy well, because there’s a big gap between giving up your privacy and getting bitten in the butt by that disclosure. It’s like obesity, or smoking—anything where the action and consequences are widely separated is going to be something that people have a hard time learning about. If every forkful of cheesecake immediately turned into a roll of fat, it would be a lot easier to figure out how much cheesecake was too much.

So kids spend a lot of time thinking about being private from parents, teachers and bullies, but totally overestimate how private they’ll be from future employers, their government, and police. And alas, by the time they figure it out, it’s too late.

There’s good news, though. You don’t have to choose between privacy and a social life. There are good privacy tools for using the net without having to surrender the intimate details of your personal life for future generations of data-miners. And because millions of people are starting to freak out about surveillance—thanks to Snowden and the journalists who’ve carefully reported on his leaks—there’s lots of energy and money going into making those tools easier to use.

The bad news is that privacy tools tend to be a little clunky. That’s because, until Snowden, almost everyone who cared about privacy and technology was already pretty technologically adept. Not because nerds need more privacy than anyone else, but because they were better able to understand what kind of spying was possible and what was at stake. But as I say, it’s changing fast—this stuff just keeps getting better.

The other good news is that you are digital natives, at least a little bit. If you start using computers when you’re a little kid, you’ll have a certain fluency with them that older people have to work harder to attain. As Douglas Adams wrote:

- Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

- Anything that’s invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it.

- Anything invented after you’re thirty-five is against the natural order of things.

If I was a kid today, I’d be all about the opsec—the operational security. I’d learn how to use tools that kept my business between me and the people I explicitly shared it with. I’d make it my habit, and get my friends into the habit too (after all, it doesn’t matter if all your email is encrypted if you send it to some dorkface who keeps it all on Google’s servers in unscrambled form where the NSA can snaffle it up).

Here’s some opsec links to get you started:

- First of all, get a copy of Tails, AKA “The Amnesic Incognito Live System.” This is an operating system that you can use to boot up your computer so that you don’t have to trust the OS it came with to be free from viruses and keyloggers and spyware. It comes with a ton of secure communications tools, as well as everything you need to make the media you want to send out into the world.

- Next, get a copy of The Tor Browser Bundle, a special version of Firefox that automatically sends your traffic through something called TOR (The Onion Router, not to be confused with Tor Books, who publish my novels). This lets you browse the Web with a much greater degree of privacy and anonymity than you would otherwise get.

- Learn to use GPG, which is a great way to encrypt (scramble) your emails. There’s a Chrome plugin for using GPG with Gmail, and another version for Firefox

- If you like chatting, get OTR, AKA “Off the Record,” a very secure private chat tool that has exciting features like “perfect forward secrecy” (this being a cool way of saying, even if someone breaks this tomorrow, they won’t be able to read the chats they captured today).

Once you’ve mastered that stuff, start to think about your phone. Android phones are much, much easier to secure than Apple’s iPhones (Apple tries to lock their phones so you can’t install software except through their store, and because of a 1998 law called the DMCA, it’s illegal to make a tool to unlock them). There are lots of alternative operating systems for Android, of varying degrees of security. The best place to start is Cyanogenmod, which makes it much easier to use privacy tools with your mobile device.

There are also lots of commercial projects that do privacy better than the defaults. For example, I’m an advisor to a company called Wickr that replicates the functionality of Snapchat but without ratting you out at the drop of a hat. Wickr’s got plenty of competition, too—check your favorite app store, but be sure and read up on how the company that makes the tool verifies that there’s nothing shady going on with your supposedly secret data.

This stuff is a moving target, and it’s not always easy. But it’s an amazing mental exercise—thinking through all the ways that your Internet use can compromise you. And it’s good practice for a world where billionaire voyeurs and out-of-control spy agencies want to turn the Internet into the world’s most perfect surveillance device. If you thought having your parents spying on your browser history sucked, just wait until it’s every government and police agency in the world.

Cory Doctorow is a science fiction author, activist, journalist and blogger—the co-editor of Boing Boing and the author of the bestselling Tor Teen/HarperCollins UK novel Little Brother. The paperback edition of Homeland, the sequel to Little Brother, is available now.

Thanks for this–have just linked it to my wiki page on Digital Dossiers, which my HS seniors are creating at this moment. Program or be programmed.

Very, very well stated.

Another thing to add: Its downright comical to think that lessons from the past don’t apply in the digital age. As a wise man once said, “There’s nothing new under the sun.” Anything digital has an analog equivalent that we can learn from.

It’s a little bit funny, and a little depressing… I didn’t read the byline before starting the article, and I didn’t need to read too far before realizing it was Cory Doctorow. You shouldn’t be such an obvious voice in the wilderness…

Thanks Cory. Thanks Edward Snowden.

> So kids spend a lot of time thinking about being private from parents,

teachers and bullies, but totally underestimate how private they’ll be

from future employers, their government, and police.

I think you mean overestimate.

Very persuasive, with practical admonitions.

Could you provide a source/link for the “forced log in to Facebook” example?

So, I recently got this job that basically requires me to stalk people on the internet. NSA, you’re thinking? Social media? Nope. Insurance. I can trace families based on nothing but obituaries, intellius.com profiles, and geneologybank. And I am actually doing this to GIVE people money, even if not very much. Anyway, my point is: tracking people pre-internet was actually not that difficult, if you were the kind of family who had an obit printed naming the surviving relatives. And many people were. I seriously hand out a thousand or so bucks a day based on who the times-picayune identified as your next of kin.

My point being, it is the tendency of human beings to create and reward social networks. Twenty years from now, whatever new college grad has my job will be sending beneficiary search letters based on facebook profiles. NBD.

While this is an excellent article, can we please get intelligent writers to knock off the harmful analogies? Obesity =/= overeating, and overeating=/= obesity.

Literally — you keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.

MadLogician @5: Fixed, thanks!

This is a fantastic read, Cory. I was wondering if I can translate it into spanish and post it in my blog? Is the article under CC license? Thank you for your reply!

This article seems rather confused in what it wants to argue and makes the major error of conflating two very different issues because they both are connected to privacy.

On the one hand, it discusses the problems of our cultural norms for how we use social media being somewhat lax on the issue of controlling the release of online information. Cory wants us to believe that this is because the interest of the social media giants like Facebook is to provide targeted ads for us. But it forgets that advertisers want data from Facebook in a very different way to other people. They are not concerned with finding out about one particular individual and could not in fact care less. Rather, all they want is to identify a market for their services. So, it is in no way connected to Facebook’s self interest whether or not people reveal enormous amounts of online information to strangers – they are perfectly happy if people reveal it only to friends, so long as it is on their servers. But of course, it is easier to play the demagogue and appeal to popular fears of “billionaire voyeurs” even when they are not actually interested in causing the problems Cory writes about. Until advertisers start auctioning to third parties the information they have on a specific individual they sell to, the above issue is moot.

(To be clear, I’m not claiming that the issue of how much advertisers know about us isn’t a problem, but it’s certainly not the same concern as what this article spends all of its time complaining about.)

And it seems fairly clear, judging by the fact that awareness of the problems of online privacy is widespread but conversations about it have little currency amongst the general population, that people are by and large happy with their control of these matters. For every individual deactivating their Facebook account between uses, there are 20 who don’t.

On the other hand, it goes into the problem of NSA surveillance. In this case we have a release of information in a manner completely counter to the implicit contract of using social media websites. When data is uploaded, users expect that they know who the recipients are. They realise that the company owning the servers will see it, advertisers will be aware of it and that their choice of privacy settings will specify who of the rest of us will come into contact with it. When government agencies tap into these systems and collect information, it does not matter how good your social norms for privacy (in the sense of privacy controls) are, but only whether or not your data is encrypted. The problem is distinctly *not* that “all their private data was being sucked out of their computers and into Facebook’s”, but rather that by legal intimidation, this data was being handed over quietly to a third party. No private body has the clout to do the same.

It’s very important to ensure that we separate these two discussions, because they warrant very different solutions.

The expression ‘scot-free’ has nothing to do with Scots, and doesn’t require an initial capital.