In a new feature for the Tor UK blog, authors share their favorite scenes from film, TV, and books. The wonderful Brian Staveley, author of the David Gemmell Morningstar Award winner The Emperor’s Blades and its sequel The Providence of Fire, explains why one little drink in Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven leads to so much trouble…

I was a sophomore in high school when I first saw Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven. I hated it.

I’d been raised on HS&GS—Horse Shit and Gun Smoke, my dad’s acronym for Westerns—and I’d come to expect a few things out of a movie starring Eastwood. I expected him to grimace. I expected him to slouch indifferently in his saddle as he rode into town. And, more than anything, I expected him to kick ass.

In the opening scenes of Unforgiven, however, Eastwood’s character—William Munny—can’t shoot a can off a post at twenty paces. He’s a tired, over-the-hill gunslinger, a man who’s lost his will, nerve, and savagery, an outlaw turned pig farmer who falls in the mud whenever he tries to catch a pig. There are hints and intimations that he used to be dangerous, deadly, terrifying—especially when he was drunk, which used to be all the time—but by the time the movie starts, he’s sworn off both violence and whisky. He’s desperate for money—needs to take care of his two kids—and so he reluctantly accepts One Last Job. It seems unlikely that he’ll succeed at it. In fact, he doesn’t seem likely to succeed at anything. For the first four-fifths of the movie he looks, moves, and talks like a busted up old man. As a high school sophomore, I wanted nothing more than for him to get over it, to get his act together and start shooting people. That’s what I was there for!

Then we come to THE SCENE. William Munny’s old (and only) friend, the only truly likeable character in the movie, a character Munny dragged into this job, has been brutally killed. We, the audience, learn the news at the same time as Munny himself, and we’re so amazed at this turn of events, so focused on figuring out just how things could have gone so horribly wrong, that we don’t even notice (at least, I didn’t) that Munny has quietly taken the whisky bottle and started drinking.

It’s an absolutely chilling moment. William Munny may have become old, weak, and uncertain in the years since he stopped drinking, but he’s also swapped the life of a murderer to become a father and farmer. We witness, in this scene, twenty-odd years of moral progress reversed in a few moments. William Munny the doddering father is erased—he erases himself—and all that remains is William Munny, the guy I thought I wanted to see all along. And he is terrifying.

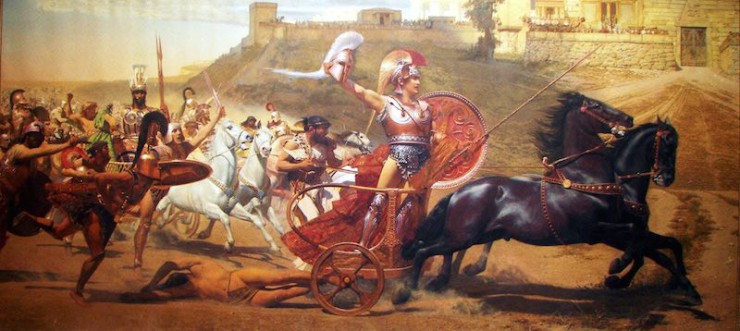

This scene reminds me—as does the movie more generally—of Homer’s Iliad. For sixteen books, Manslaughtering Achilles has done nothing more fearsome than sulk in his tent listening to music. Only when Patroklos is killed do we see Achilles, the real Achilles, emerge. That, too, is an astounding scene. When he emerges from his tent, unarmed, unarmored (Patroklos borrowed his armor), he only needs to scream, and the Trojans begin dying, running over each other in their haste to escape.

It’s the moment that the entire poem has been aiming toward. The first time I read the Iliad, however, in that very moment I started to suspect that I didn’t realize what I’d been asking for. Whatever moderation Achilles might have had, whatever human restraint, has been scoured utterly away. He becomes the perfect killer, slaughtering unarmed men he spared only months before, carving apart helpless Trojan prisoners, utterly heedless of their pleas, indifferent, even, to his own honor. When Hektor, mortally wounded, begs for a noble burial, Achilles replies, “No more entreating of me, you dog […] I wish only that my spirit and fury would drive me to hack your meat away and heat it raw…” (Trans. Lattimore)

William Munny, too, will have his aristeia, the unstoppable killing spree that I thought I wanted from the very start. When it finally comes, however, it isn’t triumphant. It is terrible in the oldest sense of the word, which comes to us from the Greek, treëin: to tremble.

Brian Staveley’s debut novel The Emperor’s Blades won the David Gemmell Morningstar Award 2015 and is out now in paperback. Its sequel, The Providence of Fire, is out now in paperback.

Well written post. This isn’t a movie I can say I loved… but I appreciated it, deeply, and it is deserving of its place as the summit of Westerns.

I had never made the connection between Munny and Achilles before. I wonder if it was intentional?

I LOVE this movie. For me the best moment of that scene is when Gene Hackman spits his “see you in Hell!” one liner at Eastwood, and we are trained by action movies to expect Munny to retort something like “I’m looking forward to it!” or “I’m already there!” But he’s just silent for half a second, and then he mutters “yeah.” There’s so much resignation and self-loathing in that moment. He can’t be hurt by those words, he has already accepted that he’s an evil man, and he’s past caring.

And then he walks out and off-handedly kills a man at point blank range, without even looking at him, as he goes out the door. Amazing.

Deservedly, one of the top 3 westerns of all time, and arguably a strong #1.

Little Bill Daggett: Well, sir, you are a cowardly son of a bitch! You just shot an unarmed man!

Will Munny: Well, he should have armed himself if he’s going to decorate his saloon with my friend.

Whole lot of William Munny in Abercrombies Bloody Nine thats for sure.

I taught this film a lot at GW. Not surprisingly, when I saw it in the theater, and the final blow-out roars, the live crowd went nuts. At that point I disliked the film, until I could not quite allow it to drift from memory. Seeing it only a few months later, I was amazed. At the time, in a bit of well-meant hyperbole, a Film Comment critic called the climax the best single moment of a director directing himself since Welles in “Chimes at Midnight,” or Chaplin in “City Lights.” When I continued to watch, noting the moral vacuum at the center, it became a much more complex, stripped-down “morality play,” commenting so much on storytelling in general – the creation of myth; it was also a kind of brilliant end of the west coda in the manner of “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence.”

I don’t deserve this. I was building a house.

Deserve’s got nothing to do with it.

A stark vision, indeed.

Spot on! I was a few years older when it came out, and I absolutely loved it. I haven’t seen it again in far too long.

Love it or hate it this movie had a story better than most western films. It also had interesting and colorful side characters, not weaker than main characters, that’s always great strength of a film. Only other western with such good story I can think of is The Homesman

When neither side in a conflict will back down this is an inevitable result. Rightly or wrongly the “sporting ladies” of Greelies bar were not willing to let go the assault and maiming of one of their own in exchange for horses paid to Mr Greelie (the deal Little Bill tried to get them to take) or even when one of the cowboys offered the injured lady the best pony of the lot. They put together a reward of $1000 in gold (in an era when a horse might sell for $5, and a revolver for $10), and offered to pay for those cowboys to be killed.

Eventually they were, and things escalated as the author pointed out. The aftermath of the carnage of the night Bill Munny killed Little Bill is not mentioned in the film, but I would be much surprised if the sporting ladies were not run out of town, and possibly one or more of them may have died in revenge killings. The big problem with vendettas is you never can kill all the friends and family on the other side.

As social commentary, today, a woman raped and mutilated as the girl in the movie was, will get nothing at all in restitution. Our “modern” system of justice is foucused on punishment of the perpetrator, which does jack for the victims