Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale is one of the best-known and most widely-read science fiction books in English. It’s taught in high schools, it’s taught in colleges, and its Wikipedia page proudly proclaims its status as one of the ALA’s 100 most frequently banned and challenged books of the Nineties. Along with 1984 and Farenheit 451, it’s one of the holy trinity of sci-fi books that every kid will most likely encounter before they’re 21. Recipient of Canada’s Governor General’s Award and the Arthur C. Clarke Award, one of the bedrocks of Atwood’s popularity, and widely considered a modern classic, it’s both a flag for, and a gateway to, sci-fi. It’s a book the community can point to and say, “See! Science fiction can be art!” and it’s a book that probably inspires a fair number of readers to either read more Atwood or to read more science fiction.

So what the hell happened to Beloved?

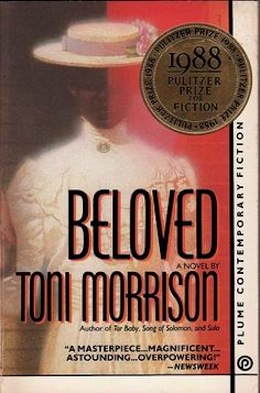

Toni Morrison’s 1987 novel, Beloved, is also on that ALA list, about eight places behind Atwood. It’s also taught in college and in high school, and it’s the book that launched Morrison into the mainstream, and won the Pulitzer Prize. It’s widely considered that Morrison’s Nobel Prize in Literature stems in large part from Beloved‘s failure to win the National Book Award.

But while Handmaid’s Tale appears on lots of “Best Books in Science Fiction” lists, I’ve rarely if ever seen Morrison’s Beloved listed as one of the “Best Books in Horror.” Beloved is considered a gateway for reading more Morrison and for reading other African-American writers, but it’s rarely held up as either a great work of horror fiction, nor do horror fans point to it as an achievement in their genre that proves horror can also be capital “a” Art. And I doubt that many high school teachers make a case for it as horror, instead choosing to teach their kids that it’s lich-a-chure.

Many claim Beloved isn’t horror. A letter to the New York Times gives the basics of the argument, then goes on to state that to consider Beloved a horror novel would do a disservice not just to the book, but to black people everywhere. Apparently, the horror label is so squalid that merely applying it to a book does actual harm not just to the book but to its readers. If horror’s going to be taken seriously (and with some of the Great American Novels considered horror, it should be) it needs to claim more books like Beloved as its own. So why doesn’t it?

Beloved, if you haven’t read it, is about Sethe, an escaped slave living in a haunted house in 1873. Another slave from her old plantation, Paul D, arrives on her doorstep and chases the ghost out of the house. Things get calm, but a few days later a young woman appears. Confused about where she came from, slightly unhinged, and knowing things about Sethe that she’s never revealed to anyone else, this girl, Beloved, could be a traumatized freed slave, or she could be the ghost of the baby Sethe murdered to keep her from being taken back into slavery. Whichever she is, Beloved’s presence soon disrupts the household, chases the healthy people away, and turns Sethe into a zombie, practically comatose with guilt over murdering her baby.

Ghost stories are about one thing: the past. Even the language we use to talk about the past is the language of horror: memories haunt us, we conjure up the past, we exorcise our demons. Beloved is a classic ghost; all-consuming, she is the sins of Sethe’s past coming not just to accuse her, but to destroy her. There has been an argument made that Beloved is just a traumatized former slave that Sethe projects this ghostly identity onto, but Morrison is unambiguous about Sethe’s identity:

“I realized that the only person really in a place to judge the woman’s action would be the dead child. But she couldn’t lurk outside the book…I could use the supernatural as a way of explaining or exploring the memory of these events. You can’t get away from this bad memory because she is here, sitting at the table, talking to you. No matter what anybody says we all know that there are ghosts.”

Literature is fun because everything is always open to multiple interpretations, but the most obvious interpretation of Beloved is that she’s a ghost. Add that to the fact that Sethe is living in a clearly haunted house at the beginning of the book, and that the book is about that most feared and despised figure in Western Civilization, the murdering mother, and that the gory and brutal institution of slavery hangs over everything, and there’s no other way to look at it: Beloved is straight-up, flat-out horror.

So why isn’t it championed more by the horror community as one of their greatest books? Sure, Morrison doesn’t run around saying that she wants to be shelved between Arthur Machen and Oliver Onions any more than Atwood hasn’t spent an infinite number of essays and interviews declaring that she doesn’t write stinky science fiction. Authorial intention has nothing to do with it. So what’s the problem?

One of the problems is that science fiction is still open to what Atwood is doing. Handmaid’s Tale engages in world-building, which is a big part of the sci-fi toolbox, and it features spec fic’s favorite trope of an underground resistance fighting a repressive, dystopian government. Beloved, on the other hand, doesn’t engage in the subject matter that seems to be preoccupying horror right now. Horror these days looks like an endless shuffling and reshuffling of genre tropes—vampires, zombies, witches, possessions, haunted houses—with novelty coming from new arrangements of the familiar pieces.

What Morrison wants to do, as she puts it, is make her character’s experiences felt. “The problem was the terror,” she said in an interview. “I wanted it to be truly felt. I wanted to translate the historical into the personal. I spent a long time trying to figure out what it was about slavery that made it so repugnant…Let’s get rid of these words like ‘the slave woman’ and ‘the slave child’ and talk about people with names, like you and like me, who were there. Now, what does slavery feel like?”

Making experience visceral and immediate is not considered the territory of horror anymore, unless you’re describing over-the-top violence. Writing to convey the immediacy of the felt experience is considered the purview of literary fiction, often dismissed as “stories where nothing happens” because the author isn’t focused on plot but on the felt experience of her characters. Horror has doubled down on its status as genre, and that kind of writing isn’t considered genre appropriate. It’s the same reason Chuck Palahniuk isn’t considered a horror writer, even though he writes about ghosts, witchcraft, body horror, and gore.

There are other reasons, of course, one of them being the fact that we’re all a bit like Sethe, trying hard to ignore the ghost of slavery that threatens to destroy us if we think about it too long. But the bigger reason, as I see it, is that horror has walked away from the literary. It has embraced horror movies, and its own pulpy 20th century roots, while denying its 19th century roots in women’s fiction, and pretending its mid-century writers like Shirley Jackson, Ray Bradbury, or even William Golding don’t exist. Horror seems to have decided that it is such a reviled genre that it wants no more place in the mainstream. Beloved could not be a better standard-bearer for horror, but it seems that horror is no longer interested in what it represents.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today; his most recent novel is Horrorstör, about a haunted Ikea, while My Best Friend’s Exorcism (which is like Beaches meets The Exorcist) will be out from Quirk Books on May 17th.

I’m generally a big re-reader, but Beloved is one book I cannot bring myself to re-read (even as I can’t bring myself to get rid of my copy). That book harrowed my soul, and I don’t say that lightly.

Wow…could that piece be any more facile? Is Beloved comparable to any horror story by Stephen King or H.P. Lovecraft? The comparisons are absurd. Morrison’s intention was not to scare the bejeezus out of the reader or give them shivers up their spine,ergo, it is not a horror novel.

And despite the writer’s absurd claim that “Authorial intention has nothing to do with it”, yes, in fact, it does. Which is to say, this writer obviously intends to have his piece taken seriously, or I assume he does. And to be taken seriously, he needed to make a compelling and rigorous case, which he manifestly does not.

This is an interesting take. I, too, struggled with Beloved and can’t imagine ever reading it again — it was seriously soul-destroying “horror.” It interests me that Lovecraft and Poe – deeply literary, deeply into “horror” – CAN be considered horror, and not so much this novel.

Beloved is indeed a scary, scary book, though. And I agree with the author that Morrison’s intention was to scare the crap out of the reader — but not just for the sake of shivers. She wanted to leave the reader thinking, “wow, this slavery crap was seriously ruinous,” and for us to imagine Sethe’s babies coming after us… which gives me a shudder, anyway.

Horror like King or Lovecraft is scary and shocking in a “fun” way. It is so far removed from reality that one can feel scared in a disconnected alternate reality. It is similar to the feeling of mortal peril that a rollercoaster induces. It is close enough to get your adrenaline pumping but safe enough for it to be fun. Beloved crossed a line to a point where in now way can it be considered safe, disconnected or fun. It was deeply horrifying and left me devastated for weeks, if not months. I still see the book on my shelf and just the sight of it (years since I read it) will induce a pang of fear –as if the spirits truly inhabit those pages (I don’t dare read it again), and yet I keep it to remind me of how it changed me. I think it would be glib to lump it in with genre works, and more appropriate to group it with the horror of Shakespeare’s tragedies or some of Dickens darker works (for example The Chimes).

Yes, Beloved is horrific. To say it isn’t is to have a very narrow definition of horror. There is quiet horror, there is splatterpunk, and there is everything in-between—psychological, supernatural, classic horror, etc. Horror does not have to simply terrify, there is tension, there is foreshadowing and unease, so many different ways to scare, to frighten, to unsettle. You could also include some of Cormac McCarthy’s work, Blood Meridian, for example. What about William Gay’s “The Paperhanger?” This is part of the problem with how people define horror, they only include graphic, violent horror in the definition.

“It’s widely considered that Morrison’s Nobel Prize in Literature stems in large part from Beloved‘s failure to win the National Book Award.” [citation needed]

“It’s widely considered that Morrison’s Nobel Prize in Literature stems in large part from Beloved‘s failure to win the National Book Award.” [citation needed]

Yes, I seriously doubt that the Swedish Academy loses much sleep worrying how to redress the injustices caused by the National Book Award decision process.

Morrison’s intention was not to scare the bejeezus out of the reader or give them shivers up their spine,ergo, it is not a horror novel.

You think she wrote a story about a traumatised woman being haunted by the ghost of the child she murdered, but it never crossed her mind that the effect might be “to scare the bejeezus out of the reader or give them shivers up their spine“? So, you’re saying she’s not too bright, this Morrison?

This piece reminds us that literary horror has deep roots, which include the Romantics, Gothic novels, the Brontes. melodrama, and most relevant here, slave narratives, and the extremely overwrought depictions of slave revolts that were written by terrified white slaveholders and their allies.

Which reminds me of how Lovecraft found horror in simply the idea of communities of non-white people.

And also reminds me of the original Haitian culture that had the idea of the zombi, a representation of the lived experience of being enslaved. And of how often Haiti has been used by white America as a symbol of everything fearful (and by lots of black American writers as a symbol of Revolution and independence). Of how easy it was to rewrite Jane Eyre as a zombie movie.

I’m thinking slavery is the ghost that haunts maybe all horror stories, at least Western anglophone horror stories. The horror of humans being made non-human, and vice versa, is one of the fundamental tropes. We live in a civilization founded on a nearly-complete genocide and built by the labor of human chattel, after all.

I’m remembering what Toni Morrison wrote in Playing in the Dark, that to forget the legacy of slavery and race while reading any American literature is to “lobotomize” it. (Zombify it?)

I think the reason I have no interest in current horror genre stuff is that it has, as this article says, completely cut itself off from these literary roots and become shallow. It resembles horror or Gothic about as much as current pop “country” music resembles real country or folk or roots music. It is a lobotomized zombie version of the genre. (Or it’s not, and I’m wrong, and Sturgeon’s law applies, and I just don’t know how to sort out the 10% good from the 90% crap.)

The horror of humans being made non-human, and vice versa, is one of the fundamental tropes.

Someone – I can’t remember who, but I think a commenter here – made the very interesting and insightful point that in our stories there are People, and there are Humans, and the two categories do not always overlap. Mostly they do; most Humans are People and most People are Humans. But when we have a Person who is not a Human, it is often (not always but often) a nice thing: an intelligent talking animal, for example. However, when we have a Human who is not a Person, it’s generally a horrible thing, like a zombie.

Capgras Syndrome may be relevant in this context.

I didn’t know about this book, I’m just new to Toni Morrison, but I’m interested. But, aftear reading this article, I don’t thinks this is a horror story, the same way Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo (the great mexican novel) isn’t a horror story, even when it’s plagued by ghosts in a ghost town above Hell itself.

Just as spaceships and robots don’t make science fiction, ghosts and scary mansions don’t make horror novels. There are horror stories where there are no ghost or the supernatural; tropes don’t make genres.

It can be a book that creeps you out, it certainly looks like it, but it was not intended as a horror book, so what? Horror is not either the ultimate genre.

Ajay, here is (with my emphases) the first introduction of the character Topsy in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was, of course, an anti-slavery novel. I’ve always been struck by how mechanical and inhuman Topsy seems — if it were science fiction we would take the “glassy eyes,” “the thing struck up,” “unearthly . . . steam-whistle” literally and visualize her as an actual robot.

( . . . aaaand to post I have to certify “I’m not a robot.”)

I’m thinking about Philip K. Dick’s human-beings-who-are-not-human-beings, and Kazuo Ishiguro’s, and Art Spiegelman’s. I don’t think everything that deals with this theme is the horror genre, but this theme is someting Toni Morrison delves into and the horror genre shares its roots with this aspect of literature.

. . . forgot to mention that Topsy was, famously, never born but “jes’ grew.”

Robot.

Why did I cry lustily during parts of this undoubtedly horrific novel? It did unquiet my soul, as I wished to finish, and then not read again. (I’ve alway read a novel twice!)!

“But the bigger reason, as I see it, is that horror has walked away from the literary.”

Most of my horror intake lately has been online, particularly the pseudopod.org short story podcast, and I’m really not seeing the walking-away. Plenty of varied, none-stereotypical and unashamedly literary writing still going on, at least in short stories.

I’ve often wondered why more horror readers don’t cite Beloved, too. Certainly in the wake of work by more recent African-American writers like Tananarive Due, it’s not impossible to see a merging of various traditions and influences.

Anyway, I find it interesting that while one probable line of influence — African-American culture — has been identified, another obvious line of literary influence remains undefined except for reference to Shirley Jackson. The psychological ghost story dates back at least to Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu (“Green Tea” for instance) and Le Fanu influenced Henry James who amplified the psychological component with The Turn of the Screw; a similar discussion/argument has played out about that novel since its publication: ghost story? not ghost story? Even as I read Beloved (admittedly quite awhile ago) I felt Morrison was tapping into that tradition. They are not exclusive; a writer can mix and merge several lines of influence and tradition and I expect that’s what Morrison was doing.

Randy M.

“Beloved is considered a gateway for reading more Morrison”

I’ve just finished reading Tar Baby, which I’d definitely recommend before Beloved as a gateway Morrison novel.

After reading Beloved, I wasn’t exactly rushing to the shelves to find another one of hers, great as it is.

We read Beloved in a Magical Realism class. It had two responses. The group around me, mostly fantasy readers, decided it was a horror novel about ten pages in. The rest of the class mainly read the books inside the program so were really focused on the “literary”. They argued hat not only was it not a horror novel, it had no speculative elements. They felt the narrator was unreliable. I think that may be a big part of the problem, as many people in academia seem to hate any sort of speculative fiction.

As as to beloved itself, it’s kinda hard to argue that it’s not a story about a vengeful ghost, so how is that not horror?

I’d also say that there is definitely a lot going on in literary horror right now. Especially in short fiction. Just look at the works of Alyssa Wong, or anything in one of Ellen Datlow’s year’s best collections.