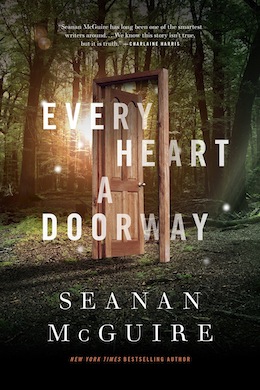

Every Heart A Doorway is another interesting novella (unless it’s just long enough to count as a short novel) to come out of Tor.com Publishing’s lists: a standalone work from the prolific Seanan McGuire. It has a solid concept and elegant execution, but ultimately it failed to satisfy me on an emotional level: for me, its narrative catharsis doesn’t work.

So, the concept. Eleanor West’s Home for Wayward Children is a boarding school and a refuge for children—mostly adolescents—who have returned from some kind of fairyland; who have come back through a door from a goblin market or the land of the dead, a country of mad scientists or a land of dancing skeletons. Children who want to go back, because in those places they felt either special or for the first time ever, at home. There is a certain undeniable whiff of Alice in Wonderland and The Wizard of Oz about these visions of otherness, along with a touch of popular-culture Peter Pan. The whole idea of readjusting to the ordinary world—a world that doesn’t believe in where you’ve been or what you’ve become—is one with many possibilities, and it seems a vastly fertile ground for stories.

We’re introduced to Eleanor West’s Home for Wayward Children alongside Nancy, a young woman who spent six (subjective) years in a land of the dead, returning to find six months had passed. Nancy is desperate to return to where she feels she belongs, and finds the school itself a bit bewildering, especially her roommate Sumi, the handsome boy Kade, and the identical twins Jack and Jill—one a mad scientist’s apprentice, the other a monster’s pet. (Those of us interested in issues of representation will be pleased to note that Nancy is asexual, and Kade is a transman.) Soon after Nancy arrives at the school, people start dying by violence. Who’s killing the students? And why?

The characters are the best part of this novella, each of them fleshed out with distinctive personalities and distinctive wants and needs in an extremely limited space. The characters, and McGuire’s entertaining sense of whimsy. There’s a great deal to like in that.

Spoiler warning, while I attempt to explain why in the end Every Heart A Doorway just didn’t work for me.

Spoiler space…

In the end, at least two of the students—Jack and Nancy—return to their respective fairylands. The conclusion is Nancy returning by simply wanting it enough, it seems: deciding and going. And the real problem I have with Every Heart A Doorway is that I don’t feel an emotional catharsis in the idea of going “home” to a special place where you are special and/or welcome to be yourself. Because for me home and self are both made things, constructed from what you do and what you are and what’s done to you: it’s the sum of one’s experiences and scars. Once you get comfortable in your own skin—or at least make peace with it—anywhere can be home. So there’s an emotional disconnect there for me.

And the lack of catharsis is heightened by the impression that the return to her fairyland doesn’t cost Nancy anything. There’s never any question that she’d make another choice, and no real sense that she’d grieve what’s left behind. And the lack of cost, of consequence, leaves me unsatisfied: it makes the conclusion, and thus the novella entire, seem slight.

Slight, but I can’t deny that it’s fun.

Every Heart a Doorway is available now from Tor.com Publishing.

Read an excerpt from the novella here on Tor.com

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books. She has recently completed a doctoral dissertation in Classics at Trinity College, Dublin. Find her at her blog. Or her Twitter.

Huh. I found the ending very cathartic, actually; I think the point of difference between us is that for me the source of tension for the book was that for all of them, they had made a home, both in the sense of ‘finding a location’ and ‘finding peace with themselves.’ Sumi, for example, had a world where her energy and “eccentricity” were acceptable and laudable. She knew who she was, and lived that way, and on her return to this world… she was a teenage girl who no longer fit her parents’ expectations, and while she was still comfortable in her skin, society was no longer comfortable with her. (There are probably children who do return and are sad, but whose parents are more accepting and help them find a place here as well, but they aren’t likely to end up at a distant reform school. There’s another school for those who don’t want to go back — I don’t expect them to be any happier there, merely more willing to force a place in this world for one reason for another.) The sadness, the melancholy, the desperation that they feel aren’t because they’ve lost a home and no longer are comfortable in their skin. It’s because they’ve been returned to a place that tells them they’re not allowed to be comfortable in their skin.

Also, I don’t think Nancy returned because ‘she wanted it.’ (And here I’m going to see if I can make the rest of this white, to hide spoilers and comments on the end of the book.) She returned because she realized that, for her at least, choosing to return was all she needed. She didn’t have to do anything to ‘deserve’ it, she didn’t have to wait for permission from someone else to go home — her decision itself, her choice and recognition of who she was, and where she belonged, were all that were needed. There was no question, no grieving, because being who you are is only difficult if you’re having to be something you’re not.

Also…. for me, at least, there was a lot of catharsis in this ending because I’d had a dark thought from the beginning of the book, that when the Lord of the Dead says ‘come back when you’re sure…’ Well, suicide is pretty permanent, and I kept hoping that the idea never occurred to Nancy. I mean, I trust Seanan McGuire a lot, but it was a hard thought to shake.

For me the ending felt oddly unsatisfying too, but the whole murder was a much bigger turnoff, it derailed what I enjoyed about this novella in the beginning much, much more. I could have read 500 pages more of Nancy getting to know all the different kids, hearing their stories and exploring Eleanor’s wayward house. But instead we get some murders out of left field and the rest after that felt pretty conventional and just not that interesting.

As for the ending, as an adult I really buy into the idea that home is wherever I am right now and I have the power to shape it into something that feels right for me, and that’s how I make a home. Kids, and especially the kids here, don’t have the same power over their environment in the same sense we as adults have, so giving in and living in a magic land where you seem to fit makes perfectly sense. But as an adult her choice feels slightly “wrong”, because she never will make the experience of molding a not-fitting-environment into something where she fits in, instead, with entering the magic wonderland, she will always be, sort of, a child in that regard.

Liz is right, I think, to note that the ending we have isn’t about the cost of Nancy’s choice — and yes, that makes the story structure look odd and wrong from a traditional perspective. Much of Mercedes Lackey’s later work — especially the “Elemental Masters” cycle — feels structurally wrong to me in the same way; her protagonists don’t grow or change, they simply overcome the Forces Of Evil arrayed against them through sheer niceness. (Although admittedly niceness is not quite the right word in the latest; From a High Tower is in its way an astonishingly ruthless book.)

Lackey gets away with this by way of what I think of as sheer narrative energy, and also because she knows her audience — the readers for these books aren’t looking for character arc, they’re there because they empathize with the fairy-tale protagonists, and the Elemental Masters cycle is explicitly about updating traditional fairy tales.

McGuire, in the present instance, is doing something a bit different. The test set by the Lord of the Dead is that Nancy must be sure of her choice before her door reopens — and in order to properly meet that test, the choice Nancy makes must be balanced, must be a choice not between merely going forward or back, but of which fork to take on the road to destiny.

The climax presents Nancy — and the reader — with exactly that choice. Nancy can choose to be Kade’s Lundy, to make a home for herself at the school and a life of service to other portal children…or she can reopen her door, and return to the Underworld. And for me, the power of the story was that, in the moment that Nancy was offered that decision, I wasn’t wholly sure which fork she would choose.

Now yes, there’s a case to be made that Nancy’s choice is essentially Peter Pan’s, that walking through her door amounts to deliberately evading adulthood. But that case itself rests on an idea of adulthood — of responsibility for others over responsibility for self — that this story and the world(s) it inhabits appear to be designed to test and challenge. And so on balance, I think the ending of Every Heart a Doorway succeeds, even if it doesn’t universally satisfy.

I absolutely loved the ending. The previous commenter’s have already pointed out why it makes sense. Nancy had to be sure, and choosing between a magical world and a world that never understood or accepted her isn’t a choice. She had to meet people who could accept her and see the possibility of a future. I remember that from being a teen myself. The way school felt like such a trap with teachers constantly insisting that this was the happiest I would ever be, that these were the best years of my life; it was so hard to cling to an idea of a future beyond school and that was what I needed.

Something no one else has mentioned, I love how this book took such an unexpected direction. If it had stuck to simply examining the lives of heroes after the story ends it would have been melancholy and overly introspective. My favorite scene in this book is the one where they have to dissolve a body in acid to cover up a murder; I would describe that scene as legitimately charming and sweet. Why should the ending have to conform to the expectations of how portal stories are supposed to go any more than the rest of the book did?

This novella was excellent and I would recommend it to any fantasy fan anywhere.

I’m going to be discussing the ending, please consider this your SPOILER WARNING…

I agree with Liz that although the novel has a wonderful setting, and I especially appreciated its dry, macabre wit, I didn’t enjoy the author’s choice of ending. It seems strange to say, but Nancy’s happy ending doesn’t feel “deserved”…. even though it bookends her story neatly and fits logically with the reason why she was sent back to our world in the first place. In fact, perhaps that’s why I didn’t like it: it felt too neat. After spending the whole novel with various characters being told that they shouldn’t hope to go home, that it’s as unlikely as being repeatedly struck by lightning, to have no less than three main characters achieve this feat seems to be too easy.

It’s not a case of “home is where you make it” for me either. I’m not opposed to people striving to go to other worlds rather than being forced to make the best of it on this one – it’s not dissimilar to the drive to “reach for the stars” shared by many a sci-fi protagonist – but the ease at which this was achieved in this case, confounding the expectations laid out throughout the rest of the novel, is what turned me off.