After his appointment as Disney’s new Chief Creative Officer in 2006, John Lasseter’s first task was to look at what projects the animation department had on hand. Some, like Meet the Robinsons, were immediately put through a rapid revamping process in a desperate effort to get a decent film out in time to meet various cross promotional contracted deadlines. Some, like The Princess and the Frog, were rapidly moved from a Disney Princess marketing concept into full production. Some, including sequels to Chicken Little and The Aristocats, were simply cancelled.

That left a few oddball projects, like the one about a TV reality star stranded in the Arizona desert, with two twists: the TV star was an adorable dog, and one of his companions was a radioactive rabbit. Chris Sanders, who was spearheading the film, had been responsible for Lilo & Stitch, one of Disney’s few bright box office moments from the previous decade. With a radioactive rabbit as a major character, the tentatively titled American Dog promised to offer some of the same wacky zaniness and hijinks, plus a cute puppy. It would also be Disney’s third full length attempt at computer animation, with animators working fiercely to combat some of the technical and artistic issues of the earlier two computer animated films.

The key word in the above paragraph: promised. Lasseter, after viewing the completed animation, felt that the film promised more than it delivered, and requested—or demanded, depending upon who’s telling the story—changes. Sanders listened to the proposed changes, and instead of making any of them, headed over to rival Dreamworks. A few years later he was happily producing How to Train Your Dragon for Dreamworks while still continuing to voice Stitch on various Disney projects.

In the meantime, Disney was left scrambling to find someone else to direct the film. Lasseter pulled in Chris Williams, who had helped transform Kingdom of the Sun from development hell into The Emperor’s New Groove, and animator Bryon Howard, who had been working as an animation supervisor, giving them 18 months to complete a computer animated film—a process that, as animators helpfully explained later, usually takes four years.

The time constraints meant that although the animators could and did throw out the idea of the radioactive rabbit (talk about missed opportunities, sigh), they were stuck with many of the other film concepts, most notably, the conceit that the protagonist dog was a TV star. But the time constraints didn’t prevent the animators from creating some beautiful moments.

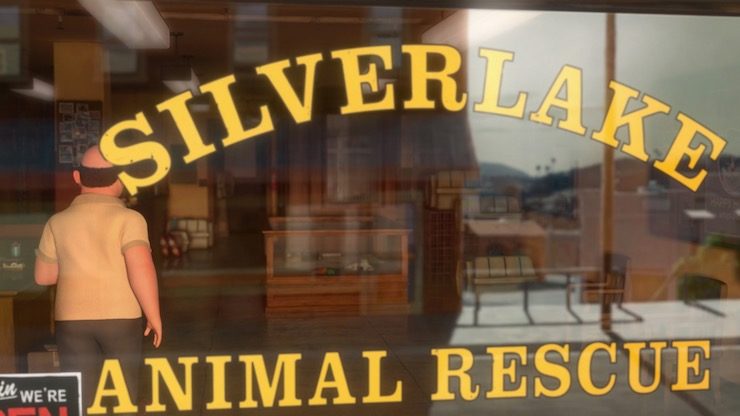

For instance, the film’s opening shot: a shop window animated so precisely that for one second, it looks like live footage, right before it shimmers and shifts into a non-photorealistic rendering of a pet shop. It was the sort of casual camera trick that Disney animators had avoided for several years, but it works beautifully here as the first shot of a film exploring the differences between television and reality.

Little puppy Bolt, I must say, is not at all interested in these sorts of deep philosophical issues, or even his fellow puppies. He wants to chew on a squeak toy shaped like a carrot. Small girl Penny finds his antics hilarious, and immediately wants him for her very own puppy. It all ends with puppy and girl exchanging delighted hugs and becoming Best Friends Forever.

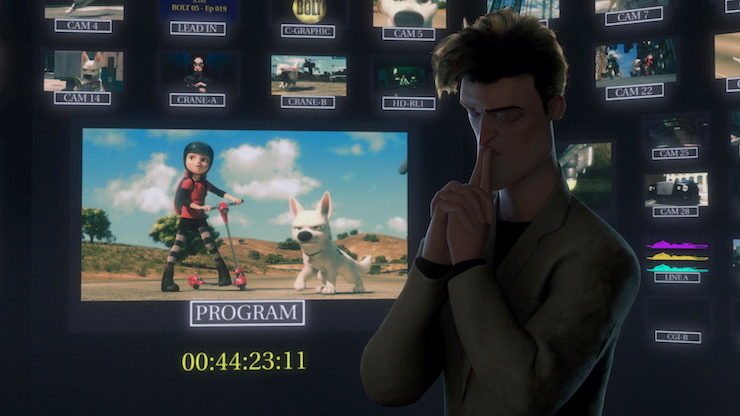

Cut to a few years later, and the sight of Penny and Bolt desperately running away from an army of evil robots before launching into a high speed car and scooter chase, complete with… dangling sound mikes. The sight of the mikes drives another character into a frenzy. No, not Penny, or the dog, or even the robots, but the director.

Because, as it turns out, none of this is real—it’s just a TV show, and the director is absolutely, positively 100% certain that the show can only work if the dog believes that everything he sees is real, and never even guesses that he’s just part of a television show. If the dog ever figures out the truth—well, the show is over, because the dog won’t be able to give a decent performance, and –

No.

Just, no.

This setup has a number of problems, including the biggest: I can’t buy the premise, at all. Which may, at this point, sound ridiculous: after all, I’ve accepted that an elephant can fly, that a little alien can find a home after crashing on earth, and that someone as uptight and responsible as Elsa really would just let it go. But I can’t believe that a Hollywood studio would go to this much effort and expense to convince a dog that really, everything he’s surrounded by is real, just so the dog can be a method dog actor. A human, just maybe—cue memories of The Truman Project—but a dog, no.

And from the one clip of the Bolt TV show we get to see, it would also be impossible—Penny and Bolt run from set to set and location to location—that is, from soundstage to soundstage. The film later confirms that, yes, the television show is filmed on various soundstages, on a large studio lot with a water tower depicting Penny and Bolt. So, how exactly does this fit with the making the dog believe that everything is happening is real? Does Bolt think that the spaces between soundstages—shown in the film—are gaps in reality caused by the evil mechanisms of the One Green Eye Dude?

Also, the cats. I live with cats. And while, I’m the first to admit that they are perfectly able to create their own reality—a reality based on the concept that humans can and should produce tuna fish after each and every visit to the kitchen, I’m also the first to admit that cats cannot exactly be trusted to go along with elaborate schemes, unless tuna fish or naps are involved, and perhaps not even then. And yet, the other two cats in the television show, both perfectly aware that this is only a television show, not reality, decide to go along with the deception, rather than ruining it. Of course, this does give them a chance to mock poor Bolt, which they enjoy, but it also seems, I dunno, just not very cat like.

Suspension of disbelief is only one problem. I also found myself more interested in the story I wasn’t getting to see—Bolt and Penny fighting off the one-green-eyed man as he tries to take over the world with only robot minions and two cats. A roadtrip across the United States—even a road trip involving an excitable hamster and an exasperated alleycat—just couldn’t quite compete, and finding out that the Bolt and Penny save the world storyline did get expanded and told in the spin off video game was only small consolation.

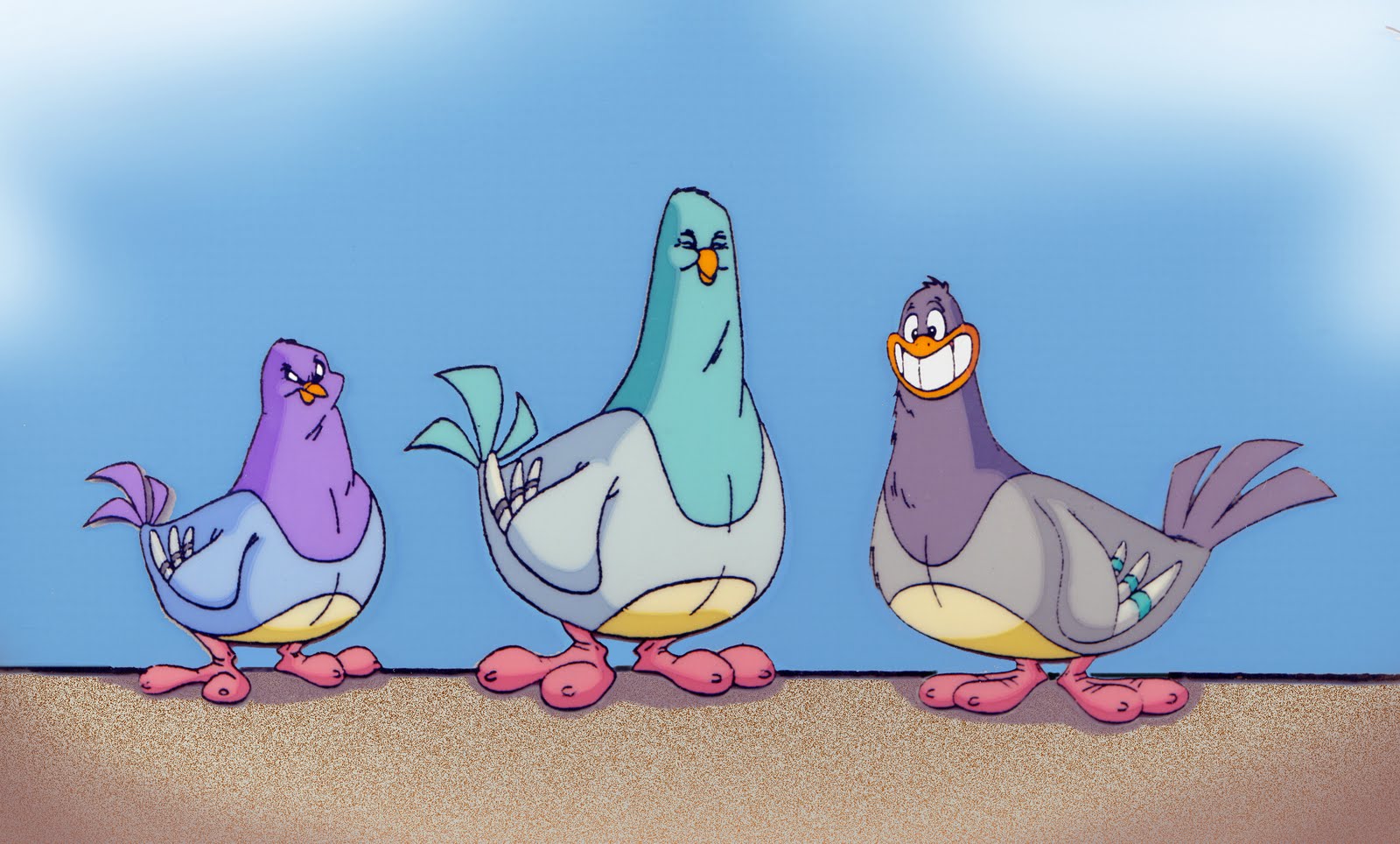

Despite this, the roadtrip is the much better part of the film. It starts off entirely by accident, as poor little Bolt finds himself shipped over to New York City, where some clever pigeons who almost, but not quite, recognize him, use his fear about Penny and his suspicion of cats to get rid of Mittens, an alley cat who has been running a Mafia-style protection ring/scam on them. Poor Mittens ends up getting thoroughly punished for this, as she winds up forced to help Bolt try to save Penny—that is, return to Hollywood, a task made all the more difficult thanks to Bolt’s belief that he has superpowers –

—and I’m back to complaining about the setup again, since the superpowers Bolt thinks he has are the exact sort of superpowers that would have been added in later by the effects department, so how did the director/crew convince Bolt that he has a superbark if the effects of this would only have appeared in post-production, long after Bolt had been returned to his trailer?

Anyway. Bolt, less skeptical than I am, is convinced that he really does have a superbark, superagility, and superspeed, a belief that Mittens finds both dangerous and terrifying. Not everyone shares her reaction, particularly a little hamster named Rhino, voiced by Disney artist Mark Walton. Rhino, a major fan of Bolt’s television show, has absolutely no doubt that Bolt is a real superhero dog, one capable of rescuing Mittens AND Penny, especially with the help of a hamster.

Meanwhile, back in Hollywood, poor heartbroken Penny has gotten a new dog from the producers, who desperately need the show to go on, Bolt, or no Bolt.

Irritating sidenote: For all of the earlier insistence on how critical and important it was to deceive the original Bolt, no one tries to deceive Bolt II. I smell “We just made up that entire condition in the first part of the film so that we’d have some sort of later plot.” But moving on.

Anyway. Can the REAL Bolt get back to his person Penny, or will he believe Mittens when the alleycat says that humans are disloyal and awful? Will Penny forget about original Bolt and bond with new Bolt? Will Bolt accept the truth about himself—and become a real hero? WILL THE HAMSTER HELP?

Ok, yes, all of this is incredibly clichéd, but also, incredibly sweet. It’s kinda difficult not to feel a tiny pang when Bolt thinks for a few horrible moments that Penny has forgotten him, after all, or to applaud when Mittens admits that yes, yes, Penny really is Bolt’s person. All together now: AWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWWW. And Rhino the Hamster is pretty awesome—and able to tell the exact moment when a television show jumps the shark. A hamster action hero who is also an excellent television critic is a rare thing.

And if Bolt’s computer animation hadn’t quite reached the point of creating realistic looking fur—that development would not happen until Zootopia, still a few more films away—the computer animation and character design was a significant improvement over Disney’s previous computer animation work, featuring some frequently gorgeous backgrounds and thrilling camera shots. Bolt, Fake Bolt, and Rhino all often look adorable, and Mittens… ok, Mittens is not adorable, or even attractive, but that’s sort of the point.

I also found myself laughing when two screenwriting pigeons and their brutalized assistant started to pitch ideas at Bolt:

Screenwriting pigeon: We got a nibble!

Other pigeon: Don’t freak out. This is how you blew it with Nemo.

Ok, it’s a terrible joke that won’t age well, but, still, I laughed.

Otherwise, all I could notice was plot hole after plot hole, and several questions about hamsters, and whether or not an alley cat, a dog, and a hamster—however adorable—could really make it all the way from New York City to Hollywood. And quite a few questions about pigeons.

For Disney, however, Bolt was a major relief after a series of critical and box office failures. Bolt received largely warm reviews, and earned $310 million at the box office—well beneath the $550.3 million earned by WALL-E that same year, or the $631.7 million pulled in by Dreamworks’ Kung-Fu Panda, but, still, a respectable sum for an animation studio that had just suffered a series of bombs. The film also spawned a video game, Bolt, which unlike the film focused on Bolt’s more exciting, if fake, TV life, and the usual merchandise of clothing, toys and related projects, and the adorable little plush Bolt is still available in limited quantities in at least one Epcot store. Streaming, DVD and Blu-Ray editions of Bolt remain widely available, and the dog makes occasional appearances in Disney Fine Art pieces.

It was the start of what is now tentatively called the Disney Revival—that is, the period after John Lasseter took over the studio until now, a period that included Disney’s last attempt at a full length hand animated feature (The Princess and the Frog), major hits like Frozen and Zootopia, and the epic story of a video game villain who wants to escape his destiny, Wreck-It-Ralph.

And, oh, another attempt at showcasing what was at the time Disney’s hands down most valuable franchise: Winnie the Pooh, coming up next.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

Disney has been playing the movie often this month. My almost 2 year old loves it, since she loves dogs. I’m treated to a song of “puppy! puppy! puppy!” for the whole show.

Yes, how the dog never saw the cameras is a major plot hole. I also figured the show runners were tired of the expense of making it real for Bolt, so that’s why Bolt II is just a well trained look alike.

I had the same reaction: Mostly fun movie, but the premise is completely nonsensical. On top of everything you mention, how the heck could they do the kind of huge, feature-quality action we saw on the budget of a weekly TV series? Let alone do it in real time? A massive freeway chase like we saw there would take weeks to film.

It’s a longtime source of bewilderment to me that TV and movies are so terribly inaccurate in their portrayal of their own industry. Almost every time you see a show or film about the making of a show or film, it’s outrageously unlike the way it would really be done — scripts being filmed in story order, massive, intricate action scenes done in a single take, backlot buildings having full interiors, entire movies being filmed and released to theaters in a matter of days, etc. It’s not like they don’t know these things are wrong, after all. It’s their own job! Okay, some dramatic license and streamlining could be justified so as not to confuse the audience or distract from the story, but so often it’s just so egregiously beyond what would be necessary for those purposes. And that’s just so weird.

simple answer: Propaganda. If they show what happens IRL in Hollywood, they assume that more people won’t go there. that’s my

Hypothesis

ChristopherLBennett – Oooh, yeah, I completely forgot about the way that television often shoots scripts out of story order. Add THAT to the many issues with the premise of this film.

I love this movie. Partially because it’s the first Disney movie I took my son to see in the theater. Partially because I had the sense that Disney animation was making a turnaround here, and I attributed that to John Lasseter. Mostly because it was just a fun action movie.

If you want an attempt at justifying the giant gaping plot hole, remember that the protagonist is a dog, and dogs trust their humans. He believes the lie because Penny acts like she believes it. He believes in himself because Penny believes in him — what’s more Disney than that? I noted on my blog after I first saw the movie that Bolt never comes off as stupid. He’s proceeding logically, even intelligently, based on what he knows, but what he knows is all based on an incorrect premise. You can absolutely question what it says about Penny’s character that she’s willing to perpetrate the lie, but she’s also willing to give it all up for her dog.

Or maybe Bolt is just so adorable that I was willing to stuff my disbelief into a sound-proof box and sit on it for 90 minutes.

I’m totally looking forward to Winnie the Pooh (since you skipped it in the Read/Watch).

I too found the premise of Bolt to be completely unbelievable. For example, cars that can be lifted up rather easily won’t fly through the air as realistically as their full-weight counterparts, rendering their explosions to be less genuine. Also, how the heck did they convince Bolt he could jump over a helicopter? It was totally the TruDog Show.

But I still enjoyed the heck out of that movie. When Bolt’s learning to be a dog, my eyes start to mist over, and in the end, when he returns to Penny at the studio, there’s inexplicably something in my eye I need to wipe away. Dust or something. Cursed Disney!

Fun fact: One of Bolt’s Lost Dog posters is on the bulletin board in the Bad Guy’s Anonymous meeting in Wreck-It-Ralph (http://findingmickey.squarespace.com/disney-animated-features/wreck-it-ralph/15444423).

@3/MariCats: If anything, it’s exceedingly rare not to shoot a script out of order, unless you’re doing a live show or a sitcom taped before a studio audience. Normally you shoot all the scenes on one set or location, then all the scenes on another set or location, etc.

Here’s a bit of trivia I’ve always liked: In movies that span enough time for a character’s hair to grow out, they often shoot in reverse order so that they can start with the actor’s hair at its longest and then trim it back as needed — since, after all, it takes much less time to cut long hair than it does to grow out short hair.

There’s also the fact that any movie or show with an animal as a main character will usually have several different lookalike animals that specialize in different things. For instance, Porthos the beagle on Star Trek: Enterprise was played by three or four different beagles. I think Comet the Wonder Horse on Bruce Campbell’s The Adventures of Brisco County Jr. was several different horses — IIRC, there was one horse used for galloping, one used for standing still, one just for jumping, and one horse they used just in scenes involving guns because it was trained not to be spooked by gunshots.

It’s even trickier with cats. The old saw is that if you need a cat in your movie to do nine different things, you need nine different cats that can each do one thing.

I heard for the Street Fighter movie they had to shoot Rual Julia’s scenes first ( starting from maybe the Final Fight) because he was losing weight so fast from Stomach Cancer

You’re nitpicking the reality-show premise but fail to mention that the hamster ball is WAY TOO CLEAN for anyone who knows anything about hamsters.

Also, this film turned my niece into an artist, who started out drawing only Bolt-related characters, eventually branching out into Manga and computer animation and is now on scholarship at the Ringling College of Art & Design, so it can’t be all bad.

I always like this movie once you get over the Truman the dog thing but, I’d really wanted to watch BOLT the super hero dog show, rather than the story shown . It looked really cool.

Never seen this and don’t especially want to.

Did they forget that The Rescuers also featured a girl named Penny? Originality fail.

@5: The Read-Watch did feature Winnie the Pooh — the book at http://www.tor.com/2015/08/27/a-bear-with-little-brain-winnie-the-pooh-and-the-house-at-pooh-corner/ and the original film at http://www.tor.com/2015/09/03/a-bear-of-very-little-brain-but-a-lot-of-money-disneys-the-many-adventures-of-winnie-the-pooh/

@9/Aerona: Huh? There are lots of fictional characters named Penny. Inspector Gadget’s niece; the younger Robinson sister who was Lost in Space; the female lead on The Big Bang Theory; MacGyver‘s scatterbrained friend played by Teri Hatcher; etc. It’s not an uncommon name.

And don’t forget Jenny in Oliver & Company.

Yeah, but most of those weren’t also made by Disney.

@8. Yeah. I would have watched that show if Disney spun it off onto XD or something.

@9. I meant Winnie the Pooh the movie, not The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh. A simple thing to confuse, I guess, especially if you’re a cowboy of very aetheric brain. (I’ve read the Pooh books to my daughter like a dozen times. Whenever I finish The House at Pooh Corner and ask what she wants next, she tells me she wants to start over with the first one, so they’re part of my subconscious mind now.)

@11/Aerona: I still don’t see the problem. Like I said, it’s a common name. And there are other Disney productions that have had characters named Penny, such as 101 Dalmatians and Sky High.

Besides — The Rescuers was a work of fiction about animals on a quest to save a girl named Penny. Bolt, a character who mistakes fiction for reality, is an animal who believes he’s on a quest to save a girl named Penny. Maybe the similarity is an intentional homage?

Good points. And I had forgotten about the 101 Dalmatians one.

This movie is a personal favorite, what can I say? Love the three groups of regional pigeons. Love that there’s no villain. Love that Mittens is understood to have good reason for being cynical, and that she is given time and significant experience in the course of which to change her mind. Love that Mittens’ cynicism and Rhino’s fanboy hero worship are both helpful, in their way. Love that the hero dog is traveling thousands of miles to come home to a GIRL. (Almost all dogs in the literature/media of my youth were a boy’s best friend.)

I don’t know how children react to the premise, when they are old enough to understand it but not old enough to know exactly how TV shows are filmed. Maybe they’re OK with it? Seeing the movie as an adult, I was quite willing to go along with the silly premise. Because it sets up what I see as the heart of the story: the disillusionment of growing up. Babies with decent parent-types believe that they can magically get their needs filled, until they grow up and find out, no, they can’t always pull that off, but it’s OK. Children half-believe that their wishes and feelings have real-world effects, until they eventually learn otherwise. Bolt gets to stand in for all our wounded narcissism. What, I don’t have special powers? Bolt doesn’t just have to learn to be a dog rather than a TV actor; he has to learn that he’s not super, that he doesn’t have magic powers to get what’s most important to him or to protect those he loves. But that’s OK! There are compensations, like the fun of being a regular dog. And friends, who also aren’t super but who are awesome. And you and your human can find each other and everyone can come through dangers safely even without superpowers.

Also, @6 CLB, in the TV shows starring heroic dogs, the dog was basically played by one dog, although there might sometimes be a stand-in dog, say, for a scene where Lassie gets covered in mud, so you don’t lose lots of time cleaning the dog-actor off. The creators of “Lassie” found that the child watchers spotted it instantly when a very-similar-but-different dog played Lassie, e.g. when the current Lassie-actor was sick. A stand-in could only be used briefly in a scene where it wasn’t clearly or fully seen. And in the case of “Lassie,” the stand-in was always a brother, since all the dog-actors who played Lassie on the TV show were descendants of Pal, the original MGM Lassie.

@15/Saavik: Yeah, “Lassie” was usually played by a male, wasn’t “she”? Amazing how often that happens with animals on film/TV. Two of the three dogs that played the male beagle Porthos on Enterprise were female. Realistically, Bolt might well have been female…

I love Bolt. I accept the premise presented to me and do not question it too much. The scenes of Bolt learning to enjoy the simple pleasures of being a dog are wonderful, and his sidekicks on the road trip are tremendously entertaining.

Yup, Lassie was always played on TV by a male collie. Two reasons: male collies are bigger than females, and thus could better pull off looking heroic and protective in proportion to the child. And female collies shed significantly twice a year, while males shed once a year and less noticeably. So when you’re filming a TV show through most of the year, you lose less time with a male. There’s a funny story about their once having to film an episode when the Lassie-actor was shedding, and one crew member was assigned to signal the “cut” whenever he could see the dog’s penis!

Originally, when they were filming the very first Lassie movie, “Lassie Come Home,” they cast a female show collie. The story of how Rudd Weatherwax’s dog Pal got the role instead of the chosen female is a *great* story, and well worth reading Lassie: A Dog’s Life by Ace Collins. Pal, an extremely smart, well-trained and photogenic dog, then got to star in the rest of the MGM Lassie movies (playing female or male dogs as the script demanded), and he and his male descendants played Lassie on the TV show.

I don’t know if it was intentional, but I find those pigeons to be very reminiscent of the Goodfeathers in Animaniacs!

Also, I can’t help but compare Mittens and Bolt to the Animaniacs characters of Rita and Runt, a cynical streetwise cat and a lovable but quite brainless dog!

@7: good point about the hamster ball. Plus, that is the world’s strongest hamster. Pushing a ladder around and the like.

I will say, when the camera pulls back and the aminals go from speaking English to making animal noises really works well.

” Almost every time you see a show or film about the making of a show or film, it’s outrageously unlike the way it would really be done…”

Chalk it up to a combination of Acceptable Breaks from Reality and Reality Is Unrealistic (ref: TVTropes).

@13: Given the nature of the show-within-a-show, I wouldn’t be surprised if Penny’s name is an homage to Inspector Gadget.

@9: Even if you’re not interested in seeing the whole movie, you should at least watch the two best scenes: the escape from the pound (Rhino’s Crowning Moment of Awesome) and the road trip montage.

@2, @22, I think that the biggest reason for not showing how movie making works in real life is that the real life process is mostly boring with multiple takes, a few gaffes, and continuity errors to be corrected

The kid? Meh. The dog? Meh. The cat? Meh.

The pigeons? OMG– I freakin’ love them!! And yes, totally reminiscent of “GodPigeons” from Animaniacs. Hubby and I still quote the pigeons to each other– they are classic!

@22 & 23: Yeah, sure, a lot of it is streamlining the complications of the process that distract from the story, but that still doesn’t justify quite how completely wrong the portrayal of the filmmaking process usually is in virtually every aspect. You’d think there’d at least be some attempt to vaguely resemble how the process actually works, even if some details were glossed over or simplified. But it goes far beyond that.

The Simpsons episode about the making of a movie (about Radioactive Man) does show a somewhat realistic take on how a movie is made, ironically. Scenes were shot out of order (when Milhouse disappears, an editor tries to make the movie work by putting previous Milhouse lines in the middle of the movie), they reshot lots of scenes to get different angles (that was why Milhouse hated being in the movie), there was only one scene that couldn’t be reshot (the very expensive one that would blow their budget if they tried more than one take), the moviemakers had to use tricks to show some things, and the trucksters were unionized and lazy. Very ironic.

This one and Cars were the movies my kid had on constant repeat and they’re still Shawshank movies for him (defining Shawshank as a movie that you will stop channel surfing for whenever you catch it regardless of which point in the movie it’s in.)

Oh, how nice to see so many others disliking Bolt so strongly. Although have enjoyed many fantastic and outlandish plots in the past, in this one my inability to suspend disbelief irked me so much, I never even finished the film.

For me, however, the proverbial straw was not anything directly related to the movie making process. No. It was the annoying, artificial scene where the dog is confused and paranoid because of feeling the hunger for the first time. Seriously? I understand what the screenwriter was going for: showing how sheltered and comfortable his life had been, but surely they could have picked another way to do it than claiming Bolt was LITERALLY NEVER hungry before? This is just extremely silly — how can you NEVER get hungry? — and I want to believe that even as a very young viewer I would find it a condescending idea to swallow.

Generally, I think some animated movies are purely designed for kids. I mean is Despicable Me (or its sequels) a realistic and believable premise in any respect? Even for movies that I really enjoyed, and others consider excellent (e.g. UP or WALL-E) there are plot holes (that Wall-E’s solar panels would last that long or that a simple machine of his type would be that able to self-repair/MacGyver new parts, etc.; that any number of helium balloons would actually lift up an actual house in North America and take it South America). Even something which, as far ‘character’ design and environment seems very realistic and well-researched, and therefore more in the realm of naturally plausible, that a clown fish could make it from that far a distance in Great Barrier Reef to the exact correct office on the other side of Australia is something which can just as easily be termed a unbelievable premise (not to mention that a forgetful fish can somehow talks to whales).

Something like The Incredibles the audience gives a pass to because they enjoy the plot – so the powers, etc., and locations (active volcano secret lairs, etc) and I believe it takes either the lack of interest in the plot, screen action or characters for you to have those ‘fridge logic’ moments as Hitchcock put it. I found Bolt enjoyable enough as a $1.99 rental but wouldn’t recommend it, see it again, and probably wouldn’t be watching it now (as with 75% of the things that were released on cable, Netflix, Hulu, theatrically, on-demand, etc.) when I have so much other material available I know I will actually find plausible and enjoyable, and so much less actual free time.

@28/Not Luke: Well, there’s hunger and then there’s hunger. There’s hunger as in “Oh, it’s time for lunch, I’ll go eat something,” and then there’s hunger as in “I haven’t had a bite to eat in three days and have no idea where my next meal is coming from.” It’s the difference between being hungry and going hungry. All of us have experienced the former, but well-off people generally never experience the latter.

@29/_FDS: The thing people often forget about suspension of disbelief is that its full name is willing suspension of disbelief. It’s not something audiences are required to do, it’s something they do by choice, and that means it’s something storytellers have to earn. Lots of stories rely on implausibilities, yes, but the storyteller has to sell those implausible ideas in a way that makes the audience willing to buy into them for the duration of the story and set aside their skepticism until later. If the unbelievable aspects are so intrusive and distracting that they pull the audience out of the story, then that’s not the audience’s fault for being insufficiently forgiving, it’s the storyteller’s fault for making it too hard for the audience to buy in.

Intelligent, talking dogs and pigeons and such are unrealistic, sure. But at least they’re consistently presented within the narrative, so we can buy them as part of the imaginary world we’re watching. But if we’re being asked to believe that a dog cannot see a boom microphone right next to him until it enters the frame of the camera pointed at the dog — no. That just doesn’t work. It doesn’t make any more sense within the world of the story than it would make in our world. We can imagine ourselves in the place of a sentient talking dog, but we cannot imagine that if we were sentient talking dogs on a set with a camera and a boom mike pointed right at us, we would somehow be unable to see the mike until the camera also saw it. It just plain doesn’t hold up.

@30: That’s true of course, but the context and reactions of other characters in that scene, made it rather unlikely Bolt was feeling the latter, “extreme” hunger, IIRC.

I think I ought to point out that Bolt’s depiction of the film and TV industry is no more absurd, implausible or inaccurate, than the average movies depiction of any other industry or profession. Some people seem to be making a big thing about this just because it is an industry with which they work and are familiar with. People who don’t work in the industry are not going to be any more bothered by a boom mike in the wrong place than they are about the other absurdities routinely seen on TV.

@32/ad: I don’t agree — I think Bolt‘s portrayal of the film industry is much more absurd and unbelievable than most other screen portrayals of same. Most depictions of the filmmaking process do get a lot of the details wrong, but they rarely go so far as to pretend that someone participating in a production could be unaware that it was a production. True, there have been instances of scenes where interlopers on a film shoot believed it to be real for a few moments, such as the Batman ’66 episode where Batman and Robin foiled a robbery that turned out to be a film scene shot by the Penguin, but as unrealistic as it was that they could’ve missed the camera crew, their confusion only lasted a minute or two. Bolt is asking us to believe that the star of the show could go for years without knowing it wasn’t reality. And that’s just stretching the gag too far.

And it’s not just a boom mike in the wrong place. It’s a script assuming that anything that isn’t in the frame of the camera is invisible to the people the camera is shooting. That’s not some obscure detail that only an industry insider would understand. That’s a matter of basic perception, understanding that what you can see is different from what a camera pointed toward you can see. That’s something even a small child can understand.

I found the fake premise at first to be more interesting than the real premise (especially with the kind of dark hook with the girl who can’t even go back to her house)! The first part of the movie dragged a little bit – fwiw while I know the conceit that they would be able to actually film an action show in such a way is ridiculous, I was willing to go with it (in some ways it seemed a bit of a jab at overly eccentric directors. Yes, completely exaggerated but that’s how the world is. This is also a world in which cats and dogs can jump out of trucks on the interstate and not get visibly hurt…and also a world in which a studio thinks nothing of tying up a little girl in a studio with real fire and then everybody running out when it goes up in flames).

However, the movie dragged at first…there is only so much mileage to be gotten from the gag of ‘dog thinks he is a superhero and does crazy things and doesn’t understand why they don’t work’. And when Rhino was introduced I cringed – but he actually ended up being far less annoying than I feared they would make him (in fact, I thought he was quite funny) and basically once the movie shifted to the road trip/Bolt figuring out how to be a real dog and that it’s OKAY that he’s a real dog – the movie seemed to really improve.

I wondered if Penny was meant to be an Inspector Gadget homage – a girl with gadgets and her dog, fighting an evil villain with a cat sidekick?

I was honestly hoping somebody would say, “The mic was in picture!” at the boom mic scene because there’s some scene from a Star Wars documentary (I can’t remember which but I think it was part of one of the DVD or VHS boxed sets) where they kept trying to film a scene and then they thought they got the take but the mic was in picture and then they all keep repeating this phrase in a really exasperated tone and it’s just become one of those things that my husband and I will randomly say to each other. And so that was my first thought when I saw the boom mic in the frame, lol.

Not seen this one and I can’t say it ever appealed. But I wonder if it would have worked better if it had been more like Galaxy Quest? The Dog knows perfectly well that it’s all a TV show, but the various animals he meets all believe it’s real and that he has super powers. Something that could work to his advantage or not, depending on the situation.

yeah i was quite convinced that when i frist watched this movie the whole relashionship of mittens and blot and rinho was well bulit up also yeah i was totattly covinced that the relashiop of those two main charaicters were paritally inspried by rita and runt and now i cant unsee it