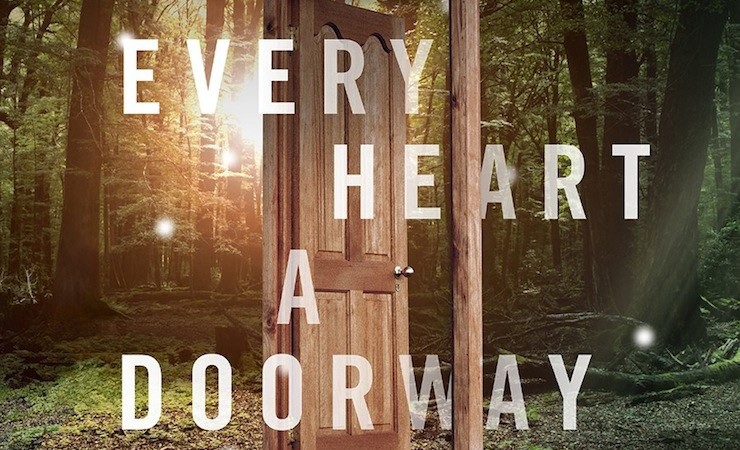

In Seanan McGuire’s brilliant (and now award-winning) short novel Every Heart a Doorway, teens who’d once escaped reality to various fairytale realms find themselves back in our world, attending a special boarding school to help them re-acclimate to “reality.” They’re all desperate to return to those places where they felt accepted for who and what they were, and one of them wants this badly enough to kill.

In structure the story is a murder mystery, but in intent it’s about the way many of us simply don’t feel like we belong in this world. We wish for a doorway, or a portal, or a wardrobe, to take us to another place, where all the things that make us different are normal. McGuire, who can pretty much write anything she puts her cursor to, does a great job conveying the kids’ pain, which of course speaks to the inner teen in all of us. No teenager feels like they belong, and most feel like freaks of some kind. It’s the same universal truth that gives Harry Potter and the X-Men their dramatic power.

But I experienced an interesting dichotomy while reading it, one that ultimately has nothing to do with the author’s intentions. I certainly identified with the characters: I was as freakish as any teen, a nerdy bookworm with thick glasses, braces and bad skin, trapped in a redneck town long before social media. My parents, who grew up during the Depression, fell into that generation’s classic conundrum: they wanted their kids to have more than they ever did, but then they resented us for not properly “appreciating” it. They certainly had no time or sympathy for kids having trouble “fitting in.”

And yet I was also struck with powerful sympathy for the parents of these desperate children. Although none appear as characters, many are described: the parents of the protagonist, Nancy, believe she was traumatized by a kidnapping, rather than escaping to the Underworld to willingly serve the Lord of the Dead. Their clueless attempts to reintegrate her into society are presented as well-meaning but disastrous, and the failure of all the parents to believe what had really happened to their children is shown as a great tragedy.

(I should clarify that this has nothing to do with the sexuality or gender identity aspects of the story. That’s an issue whose reality is beyond dispute. People are who they feel they are, no matter what anyone else, parents included, tries to make them.)

The symbolism is plain: the real world wants us to give up our childhood belief in “magic,” and that’s a terrible thing. But is it?

I’m a parent now, of three children blessed/cursed with intelligence and vivid imaginations. One in particular is likely to never “fit in.” And yet I can’t really believe that the best course for him is to totally indulge his fantasies; isn’t part of my job description to prepare him for the world as best I can? And isn’t part of that giving up belief in the childish forms of “magic”?

Or, as Bruce Springsteen says in the song, “Two Hearts”:

Once I spent my time playing tough-guy scenes

But I was living in a world of childish dreams

Some day these childish dreams must end

To become a man and grow up to dream again

That’s a paraphrase of 1 Corinthians 13:11:

When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.

But the Boss goes the Bible one better (you have no idea how much it delighted me to write this phrase) by insisting that you grow up to dream again.

To me, that’s the job of a parent: to guide your children to the point that they willingly give up their childhood magic, and embrace the magic to be found in adulthood. And there is magic in it: when you see your newborn child for the first time, it casts a greater spell than any storybook realm. And when you take your love for childish scribbling and develop it into the adult skill of writing stories and novels (such as Every Heart a Doorway), that’s a charm that can affect millions.

And yet.

The memory of my parents telling me that people bullying me was my own fault for being “weird” is, to this day, never far from the surface. I vividly recall their insistence that my cousin Rob, who picked on me mercilessly for reading science fiction, was just being “normal.” I often wonder what kind of person I’d be today if they’d had the least bit of empathy, or stood up for me against the extended family instead of shaking their heads along with them, just like the unseen parents in Every Heart a Doorway. Or if, like the kids in the book, I’d found another realm where I was accepted as I was, where “weird” was the norm.

It’s the brilliance of this book that it allows the reader to embrace these contradictory feelings without giving any easy or facile answers. Ultimately, if there is an answer, I suppose it’s this: children need guidance, and parents need sensitivity. The ratio is different for every family, but when they’re out of balance, you get real, lasting and permanent damage.

This article was originally published January 31, 2017 on Alex Bledsoe’s blog.

Every Heart a Doorway is available from Tor.com Publishing. Down Among the Sticks and Bones, book two in the Wayward Children series, publishes this June.

Alex Bledsoe grew up in west Tennessee an hour north of Graceland (home of Elvis) and twenty minutes from Nutbush (birthplace of Tina Turner). He’s been a reporter, editor, photographer and door-to-door vacuum cleaner salesman. His latest novel is Chapel of Ease, available from Tor Books.

Alex Bledsoe grew up in west Tennessee an hour north of Graceland (home of Elvis) and twenty minutes from Nutbush (birthplace of Tina Turner). He’s been a reporter, editor, photographer and door-to-door vacuum cleaner salesman. His latest novel is Chapel of Ease, available from Tor Books.

I too was a quiet bookworm of a kid with glasses and bad skin. I had a few friends I hung around to talk about fantasy novels and play AD&D in 6th grade to college. Mom still calls the super-hero, science fiction and fantasy tv shows I watch icky space things but she would never stop me from watching them. I’ve always read science fiction, fantasy, mystery and assorted other books my family is okay with that. In fact I was voted chief nerd and the last family Christmas party as opposed to my other cousins because I would still play D&D if I could find someone else to play the game with me. I guess I was more lucky than I thought. I’m on the hold list for this book at my local library it’s just not my turn yet. I look forward to it. I’d like to visit some portal fantasy but always want to come home again.

This article is spot-on about a healthy adulthood not really being a goal. I just read this book about 2 weeks ago & had a stronger reaction. One of my kids is both very intellectually gifted and neuro-atypical. In a lot of ways, the question for parents in my position is NOT “when will they give up their very different perception of the real world?” or “When will hey conform to my expectations?” but more along the lines of Will they ever be able to maintain a long-term relationship? Will they ever be able to hold a job or have a satisfying accomplishment? Will they ever be able to live independently? There’s a whole gamut of loving practical questions in the novel that aren’t noticed in the process of making the mundane parents unsympathetic. I thought Dory’s parents in “Finding Dory” were a great deal closer to the mark in their fears and heartbreak. Put another way, I think the book would have been greatly improved if it included a character who was also able to “graduate” and function in the real world or able to maintain an emotional relationship with their parents.

I think I vividly remember my mother yelling at me ” You can’t live in a fantasy.” And then she threw all my books one by one against the wall. I don’t remember what sparked that confrontation. We had a lot of them back then. She was a single mother struggling to support me in rural Alabama. I was a fourteen year old searching for worlds bigger than the one I was trapped in. That conflict never really resolved itself. She was always in some way tied up that small town and it’s values. I was always trying to break away from it. Even 40 years later and half way round the globe we would have the same fights. I have this book on my Kindle. Now I am a little leary to read it. Since my Mom died, I wish we had figured a way to meet in the middle or at least understand each other.

I guess I was lucky. I was a fairly typical nerd. Read too much, had no interest in sports, thought science was the best class of the day in school. Fortunately, my dad had no interest in sports, either. Both my parents were avid readers and encouraged me to read, and my mother shared my love of science fiction. Although I was never part of the “cool kids” I managed to avoid being relegated to the real social outcasts due in no small part I believe to my parents not squashing my personal self worth. My only regret is I didn’t reach out to those who were in that beaten down social fringe more.

Part of the message in that book for me was that the portal children weren’t just changed by finding their portals, but that they probably found them because they already were different. The worlds they ended up in just enhanced and reinforced the things in them that were already different, not-normal. Any 100% “normal” kid that ended up in one of those realms probably would have perished. And perhaps the fact that they weren’t really accepted for who they were by their families, feeling that they could never show their true selves, was true even before they went away.

As the different, ostracised child I was, I always found the endings to portal fantasy stories (Like Oz, Narnia etc) really baffling because I didn’t understand why the children wanted to return to our cruel and confusing world. Even Disney’s version of The Jungle Book had a stupid ending — why on earth would Mowgli want to leave the jungle? So Every Heart a Doorway really struck a chord with me. I had a parent who loved me, but they also struggled a lot with mental health, and I often felt more like a burden than a blessing. (That is not conducive to growing up expecting adult life and parenthood to be magical and happy.)

What I’m wondering is, does it necessarily have to be a choice between letting kids be who they are and love what they love, and helping them learn what they need to, in order to function in an adult society, if it’s at all possible? (If it’s not, why even try?) Just love the kids and accept them fully, and take pride and joy in them whoever they are, and let them find spaces where they can feel less like ugly ducklings and more like baby swans. And also, at the same time (or different times, but in parallel), help them understand about the world they will grow up in, and try and figure it out together, because their world will not be the same as ours anyway. They will need some different skills, different tools.

And perhaps try to make growing up sound less like a prison sentence and more like a new world of opportunity and adventure interlaced with the inevitable struggle, and perhaps they will be more ready for it.

Thank you for this article. I really enjoyed reading the book, but was troubled by the ending. I’m not a parent, but even I thought the world she had found happiness in was not even close to a healthy one. And I’m very cognizant that the things I desired as a geeky, lonesome teen were not choices I would make today. Definitely agree with Also a Mom that the book would have benefited from portraying a character that does indeed grow up to find happiness in the “real” world of adulthood.

I didn’t have the mixed feelings about Every Heart a Doorway that the author of this article describes, because I don’t think this book is primarily about the role of fantasy in people’s lives or about growing up. It’s about grief.

The book gives no indication that the main characters’ visits to other worlds were imagined; it treats them as real. The main characters travelled to real places, spent time and effort learning the skills needed to survive in those places, met and befriended real people. Then they were snatched away from their new lives and their new friends, to probably never see them again. They are not hanging on to childish fantasies; they’re grieving the loss of close friends and of places that felt like home.

The distance between the characters and their parents arises because the parents either don’t know what really happened to their children, or don’t believe it was real, so they don’t understand their children’s feelings. They think their children should be happy to be “home” (and should feel like this world is home, in the first place), should be exactly the same as they used to be, should be eager to return to the things they used to enjoy and forget about what just happened to them.

This would be a counterproductive reaction even if their children had actually been kidnapped, or lost, or whatever the parents believe happened, rather than in another world. Going right back to familiar routines and forgetting about why you were away from them is not always that easy, even when whatever took you away from them was entirely bad.

The founder of the school the main characters go to does not encourage them to try to go back to their other worlds; far from it. She reminds them over and over that they will almost certainly never be able to go back, that they have to move on and learn to live in the world they’re in. The difference between her and their parents is that she understands that moving on is hard work, and she gives them time to remember and to grieve.

So yes, the book doesn’t show what happens to these children in the long term. It doesn’t show them adjusting to the “real world” again. A book about that would be interesting, sure, but that’s not what this book is about.

The central emotional point of this book is the loneliness and disconnection and even horror that comes from being terrified and grieving while everyone around you smiles and carries on as if nothing is wrong, and expects you to do the same. And the lesson of this book is that you have to let people go through grief before they get to moving on. You have to be patient. Even if you’re really really sure that it’s for the best and some day they’ll be glad it happened. Even if watching them grieve for something that “shouldn’t” be important makes you uncomfortable. You have to wait for some day. You can’t make them be happy now.