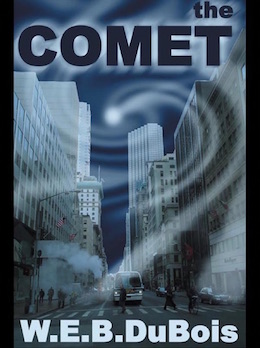

Our focus this column is on “The Comet,” a science fiction short story by W.E.B. Du Bois. Yes, as I note in the original Crash Course in the History of Black Science Fiction, that W.E.B. Du Bois: the well-known and recently misspelled critical thinker and race theorist. “The Comet” was first published in 1920 as the final chapter of his autobiographical collection of poems and essays Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil. Though nowhere near as influential as Du Bois’ monumental The Souls of Black Folk, Darkwater was popular and well-received. But by the time, almost a century later, that author and editor and Sheree Renee Thomas was compiling her own groundbreaking book, the anthology Dark Matter 1, she found this early and prominent work of science fiction languishing in completely undeserved obscurity.

WHAT HAPPENS

In early twentieth-century Manhattan, bank employee Jim Davis is sent to retrieve documents from a deep vault. (It’s made clear that this is a low-priority, high-risk errand, and that it has been assigned to Davis because he’s black.) Accidentally locking himself in a secret chamber at the vault’s back, Davis emerges after a struggle to find the entire city dead—except for a wealthy white woman who spent those same crucial moments in her photographic darkroom. Everyone else has been poisoned by the gases of a comet’s tail through which the Earth has just passed. Moving confrontations with widespread mortality give way to the woman Julia’s realization that the racial separation she’s accustomed to means nothing. Her climactic vision of Davis as Adam to her Eve is then swiftly banished by the return of her daytripping suitor: the comet’s swath of death has not been global but merely citywide.

WHY IT DESERVES ATTENTION

“The Comet” is a prime example of speculative thinking from a man on the forefront of major intellectual developments. A pioneer in the field of sociology and the author of texts foundational to the Montgomery Bus Boycott and other civil rights actions, Du Bois imagined the apocalyptic disruption of daily life as the background necessary for his depiction of true racial equality. Like many Afrodiasporic authors who’ve come after him, he deprivileged the racism inherent in the status quo by smashing that status quo to tragic smithereens. Though the dream of Utopic ages to come is conveyed only in a few paragraphs toward the story’s end and experienced by its characters in a nearly wordless communion, this dream, this communion, is “The Comet’s” crux. That a mind such as Du Bois’ used science fiction as the method to clothe his ideas in lifelikeness stands as a good precedent for those of us who do the same. If only knowledge of that precedent had not been buried and forgotten.

WHAT ISN’T ON THE PAGE

Darkwater is an intensely personal book. Most chapters other than “The Comet” relate scenes from the author’s life. Each ends in a poem full of metaphor and allegory, and these metaphors and allegories draw on Du Bois’ own experiences, reflections, and longings. Born in Massachusetts a scant two years after the Emancipation Proclamation, Du Bois lived a relatively privileged life for a black man of that period. He attended a school—integrated—and was recognized as the scion of a family with extensive local roots.

And yet, a century ago he could write with heartfelt weariness of daily microaggressions chillingly identical to those experienced by African Americans today. In the chapter just preceding “The Comet” he fends off an imagined interlocutor’s accusations of being “too sensitive” with an account of his milkman’s neglect, his neighbor’s glare, the jeers of passing children. He praises the world’s myriad beauties but then gives a harrowing account of the dangers and inconveniences of traveling to see these beauties under the baleful eye of Jim Crow.

These are the phenomena forming the original backdrop to the telling of “The Comet.”

Of course we also bring modern sensibilities to our reading of Du Bois’ story; by recognizing them as such we avoid confusing and corrupting a purely historical take on it. It’s easy from the vantage point of the twenty-first century to make comparisons to Jordan Peele’s movie Get Out or to Joanna Russ’s short novel We Who Are About To or to another of the many hundreds of stories dealing with the racial and gender issues “The Comet” brings up.

These are the phenomena forming the story’s contemporary backdrop.

To see these backdrops, change your focus. Examine the author’s assumptions: that a black man found in the exclusive company of a white woman is regarded with suspicion, for instance. Examine how they contrast with yours and your friends’: for example, that women are more than decorative childbearing organisms. Assumptions like these aren’t on the page; they are the page.

WHAT BECKY’S DOING IN THERE

Maybe you’re unfamiliar with the term “Becky,” slang for the sort of privileged young white woman who’s offended by being labeled as such. For me there’s the added connotation of strong physical attractiveness combining with racial cluelessness to make the Becky dangerous—and especially dangerous to any black boys or men in her vicinity. Julia, the heroine of “The Comet,” is a Becky. That Davis survives their encounter is an outcome resonant with the author’s unusually positive and neutral experiences of whiteness in childhood.

The Becky Julia’s presence underscores Du Bois’ dichotomous perception of the world: she is white and female in complement and contrast to hero Davis’s black maleness. Her deadliness is at first superseded by the comet’s, but when the comet’s deadliness is finally shown to be less than universal, the Becky’s returns—though not in full force, because the threats and epithets it renders Davis susceptible to remain purely verbal through the story’s end.

THE BEST WAY TO HAVE FUN WITH IT

It’s at the level of verbal virtuosity that “The Comet” is most enjoyable. Today Du Bois’ writing may seem flowery, but rather than shrinking from its apparent excesses I advise embracing them. “Behind and all around, the heavens glowed in dim, weird radiance that suffused the darkening world and made almost a minor music,” he writes, approaching the height of his rhetorical effervescence. Like Lovecraft but less turgid and more forward-thinking, Du Bois’ prose—which I confess to imitating somewhat in this essay—is a largely neglected source of exhilarating pleasure.

Nisi Shawl is a writer of science fiction and fantasy short stories and a journalist. She is the author of Everfair (Tor Books) and co-author (with Cynthia Ward) of Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction. Her short stories have appeared in Asimov’s SF Magazine, Strange Horizons, and numerous other magazines and anthologies.

Nisi Shawl is a writer of science fiction and fantasy short stories and a journalist. She is the author of Everfair (Tor Books) and co-author (with Cynthia Ward) of Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction. Her short stories have appeared in Asimov’s SF Magazine, Strange Horizons, and numerous other magazines and anthologies.

I enjoy this series. Thanks so much.

What an interesting read- thank you! I love being exposed to writing from nearly a hundred years ago and realizing how modern it is.

Thank you for highlighting this story. It sounds very much like a forerunner of Ranald MacDougall’s The World, the Flesh and the Devil (1959), which stars Harry Belafonte and Inger Stevens as the last two humans alive in a New York City depopulated by the passing of a radioactive cloud, with the late addition of Mel Ferrer as the third. Writer-director MacDougall was white, the film was a mainstream MGM production, and its ending suffers from needing to make an optimistic, reconciliatory statement about race relations without coming out in favor of anything so radical as interracial romance, but the second act dealing with the mutual attraction between Belafonte and Stevens—and the way he resists it as dangerous even in a post-apocalyptic, purportedly post-racial world while she displays no understanding of the reasons for his wariness, pressing him for a romantic response even while carelessly tossing around phrases like “free, white, and twenty-one”—echoed strongly with your discussion of Julia as Becky (and indeed, as soon as a white man shows up in the film, Belafonte is in danger from him thanks to mere proximity to Stevens). The film’s credited sources were M. P. Shiel’s The Purple Cloud (1901) and Ferdinand Reyher’s “End of the World” (1951), but was Du Bois’ story already obscure in his lifetime? It feels really close for parallel evolution.

That was a thoughtful comment, Sovay. I was only four years old when the movie you cite came out, so I can’t say if “The Comet” was obscure at that point. But by the time I was around 40 and Sheree unearthed it, the discovery was a huge surprise to me. And I’m a reasonably well-read SF aficionado.

It may have been a case of DuBois going uncredited not because the screenwriter was unaware of the work but because someone else involved in the film’s production decided it was harmful or unnecessary to mention him. That would take some digging to uncover.

I like what you’ve said so very much!

Sovay’s comments inspired me to read Shiel’s work ” The Purple Cloud.” I got more than I bargained for. I certainly did not expect to find a kind of apocalyptic dystopia emerging from two journeys: the icy expedition to the North Pole, and, unexpectedly, a journey across regions of the world, including Southeast Asia, Australia and West Asia etc. Shiel projects a dualism between Black and White Spirits. The White Spirit is “master.” He wins repeatedly, “but by a hair.” He is projected to lose ultimately. The North Pole expedition is all about bears and barking dogs, and even fratricidal murder among the adventurers, but the purple vapor that descended could well be a metaphor for imperial over- reach and the unrepentant and ominous orgy of colonial adventures worldwide. W.E. B. Dubois’ work, ” The Comet” (1920), seems to be the more direct original source for MacDougall’s film, “The World, The Flesh and the Devil,” given its storyline and its focus on race relations at the inter-personal level. Du Bois should have been fully acknowledged by the screenwriter, producer et al. Special thanks to Sovay for his insights on this issue.