Hayao Miyazaki’s 1979 directorial debut, The Castle of Cagliostro, predates the founding of Studio Ghibli. But it lays the groundwork for many of the themes that will pop up throughout the later classics that came from the Studio. Looking back at the film, it’s clear that even right out of the gate, working as a “director for hire,” and using someone else’s characters, Miyazaki still found a way to make a Miyazaki movie.

In revisiting the film, I found that it’s still a fantastic rollercoaster, zipping from rollicking heist to poignant romance to oddly dark melodrama easily, all the while punctuated by goofy, slapstick humor. On paper, this shouldn’t work, but it adds up to a marvelous film that shows many of Miyazaki’s hallmarks already firmly in place. Join me as I discuss the themes and highlights of the film—please be aware of spoilers going forward.

Before Ghibli was a studio, before Nausicäa made Hayao Miyazaki a god among anime fans, and before My Neighbor Totoro made him a god among, well, everyone, he started out as an animator for television. He eventually partnered with fellow animator Isao Takahata to create series including adaptations of Heidi, Anne of Green Gables, and a book called The Incredible Tide that the two re-titled Future Boy Conan. In 1979, Miyazaki was hired to direct his first feature: Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro, after directing 14 episodes of the Lupin III television series.

Before I dive into The Castle of Cagliostro, allow me to share some backstory: Lupin III is the grandson of Maurice Leblanc’s gentleman thief Arsène Lupin…kind of. Back in 1967, the manga artist Kazuhiko Katō wrote what he thought would be a short-lived adventure comic about a James Bond-style thief for Weekly Manga Action. He named the character Lupin III, gave him a vague ancestry to tie him to Leblanc’s beloved character, and grudgingly allowed his editor to give him the pen name “Monkey Punch.” After all, this was just going to be a few months, right?

Instead, Lupin III became a huge hit and Katō was stuck with a nom de manga that he hated. Even better, once the character became popular outside of Japan Leblanc’s estate came after him—despite the fact that Leblanc himself used Sherlock Holmes in one of his Lupin stories in “Sherlock Holmes Arrives Too Late,” and had to change the detective’s name to “Herlock Sholmes” (seriously) after a complain from Conan Doyle. After that, Lupin’s name was changed to “Rupan” or “Wolf” when he appeared outside of Japan. After a few years of popularity as a manga star, Lupin was brought to TV in a slightly more family-friendly format. While he’s a violent, lascivious bastard in the manga, Lupin is more of a bumbling cad than a straight-up rapist in the show, and while he still loves stealing, he can also be noble, helping underdogs and using his skills to be more Robin Hood than James Bond. He’s also tied more closely to his gang, Fujiko, Jigen, Goemon, and his nemesis, Inspector Zenigata, than he is in the manga.

Fujiko Mine is primarily a jewel thief, occasionally dating rich men to swindle them, and occasionally working as Lupin’s partner. Lupin is besotted with her, and every once in a while, when things are really tense, she seems to love him almost as much as her diamonds. Just in case you missed the pun, Fujiko is named after Mount Fuji, and her surname is Mine, which means “summit,” and I think it’s pretty obvious why all the mountain imagery is being used here…

Daisuke Jigen is a crack shot, and visually he seems to be based on James Coburn in The Magnificent Seven (and in turn Jigen seems to be the inspiration for Cowboy Bebop’s Jet Black) and he is completely loyal to Lupin. He haaaates Fujiko.

If Jigen seems to have wandered in from a noir film, Goemon Ishikawa XIII is straight out of a samurai epic. Goemon is the descendant of Ishikawa Goemon, a real-life 16th Century outlaw hero who robbed the elite to help oppressed peasants, and he’s an old school, enrobed, sword-wielding samurai, despite the fact that a typical Lupin plot involves heists in Monaco and cruise ship robberies. He wields an invincible blade, Zantetsuken, that can cut through literally anything.

Inspector Zenigata is a Japanese cop who works with Interpol and anyone else necessary to get to Lupin. He’s obsessed with catching the thief. He also serves as a parody of a conventional, hard-working member of Japanese society—and a symbol of the life that Lupin fears most.

The Castle of Cagliostro was Lupin’s second movie, and it’s a striking departure from his usual capers. My guess is that people heading to the theater to watch a Lupin movie did not expect to find a touching story of lost love buried in all the burglary and fight scenes, and in fact, the film was not successful on its initial release in Japan. As Miyazaki’s reputation grew, however, more people revisited it, and as a result it’s often people’s introduction to Lupin’s world.

The plot begins as a conventional Lupin story, but quickly veers into new territories: Lupin and Jigen rob a Monte Carlo casino, but soon realize that their haul is counterfeit. But who could make bills so perfect that a respected casino couldn’t spot the fakes? Why, the tiny sovereign nation of Cagliostro, currently under the thumb of an evil Count. As luck would have it, Lupin and Jigen literally run into the Count’s bride, Clarisse, as she tries to escape her wedding. After the count re-kidnaps her, Lupin decides that he and Jigen will rescue the girl and expose the counterfeit ring. Goemon and Inspector Zenigata are called in as reinforcements, and Lupin soon discovers that his old flame Fujiko is already working for the Count, deep undercover as the bride’s maid/tutor/prison guard. With all the players in place, the plot zigs and zags through a rescue attempt that gets Lupin thrown into a dungeon, another rescue attempt that gets Lupin shot, and, finally, Clarisse and the Count’s terrifying Gothic wedding, which culminates in yet another rescue attempt, and a final battle inside a clocktower.

Oh, and about that terrifying Gothic wedding? Here’s the Count’s idea of groom attire:

Unlike most Miyazaki films, The Castle of Cagliostro has a true villain—in case you couldn’t tell from that vampiric cloak. The dastardly Count has no ulterior motive, he simply wants the treasure of the Cagliostros. The only possible depth comes when he says that his side of the family are seen as the “dark” Cagliostros, while Clarisse is lucky enough to be one of the “light” and that, while she was raised to be good, her father the Grand Duke ordered the “dark” side of the family to do all the necessary dirty work. (Hence the need for the corpse-stuffed dungeon we see later in the film.) But that’s only a tiny moment of ambiguity, and it’s not nearly enough of a counterweight to “horrible older man who’s forcing a teenage girl to marry him so he can steal her family’s money, while pretending to the press that they’re madly in love and the relationship is totally consensual.”

Is there a counterweight for that? Probably not.

Miyazaki co-wrote the film, and most likely drew on La Justice d’Arsène Lupin (which featured a counterfeiting plot) and The Green-eyed Lady (which featured a treasure at the bottom of a lake) and combined those elements with research he had done for a failed Heidi adaptation to create a whimsical alternative Europe similar to the one he’d later create for Kiki’s Delivery Service. He also included a fun little autogyro to have an excuse to animate flight, which obviously became one of his greatest directorial hallmarks.

Now, as I said, Cagliostro wasn’t considered a hit when it was released, but it’s had a surprising amount of influence. In 1981, a clip from the film was shown at the Disney Studios, where it served as an inspiration to a young John Lasseter, who was committed to the idea that animation should be for everyone, not just small children. (Lasseter also wooed his future wife with clips from the film, which is just sweet.) Nearly twenty years later, Lasseter is the one who stepped in to get Ghibli movies better distribution in the US, ensuring that kids could watch great dubs of Spirited Away and Castle in the Sky, while anime-loving adults could watch the subtitled films and dive into commentary tracks and behind-the-scenes footage.

Lupin’s climactic clock tower confrontation was also, er, lifted? is that fair to say? and dropped into the climactic confrontation between Basil and Ratigan at the end of The Great Mouse Detective, down to Basil and Ratigan wrestling over Olivia Flaversham in turning clockwork…

…just as Lupin and the Count wrestle over Clarisse…in turning clockwork.

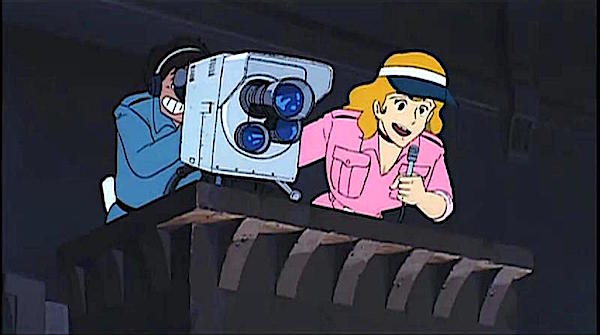

The Castle of Cagliostro has inspired two big rumors over the years. The first is that Steven Spielberg saw a screening of the film in the ’80s, loved it, and based an action scene on the opening car chase. One of the later DVD releases even quote him on the cover calling it “one of the greatest adventure movies of all time.” I couldn’t find anything to confirm it, as, unlike Lasseter, Spielberg has never gone on record as a fan. The other rumor is that when Japan’s Princess Sayako married Yoshiki Kuroda in 2005, she based her wedding dress on Clarisse’s. I also couldn’t find any confirmation on that, although just looking at the dress I don’t see the similarity. Finally, and this might be a stretch, but I choose to believe that Fujiko’s reporter jumpsuit inspired April O’Neill’s fashion.

Clarisse and Fujiko

I remembered this as a fun, fluffy movie, but what struck me rewatching it was how Miyazaki managed to smuggle an interesting theme into this heist film. While Miyazaki barely uses Jigen and Goemon (making Lupin more of a lone wolf figure than he is in his other outings) he does make a character choice that would soon become a constant in his filmography: an experienced, mature woman is contrasted with a young ingénue. But not in a competitive way, or even in a standard mentor/mentee type of relationship. Rather, the two women each have their own skills and strengths, and treat each other as respected equals. Here the pair is Fujiko and Clarisse.

The two women embody two very different archetypes of femininity. In the Lupin III manga and anime, Fujiko is a femme fatale/sexpot, trading on her looks and charm to work her way through high society, dating rich men, lifting jewels, and occasionally working as a spy. She’s been hugely popular since her debut, and has starred in a prequel TV series, Lupin III: The Woman Called Fujiko Mine. In Cagliostro, however, Miyazaki dials down her sexuality in favor of making her an action hero, able to embed herself into Cagliostro’s household, only to turn around, ally herself with her usual nemesis Zenigata and pose as a TV reporter to help expose the counterfeiting scheme, all while defending herself from the Count’s goons. Rather than using feminine wiles, she sticks to machine guns and grenades. She also takes a moment to warn Clarisse that Lupin is a playboy—and this is a telling scene. She isn’t jealous of Clarisse, or worried that Lupin will hurt the girl—she just goes slightly out of her way to let Clarisse know what she’s in for if she decides to pursue a romance.

Clarisse, meanwhile, is considered by some to be ground zero for “moe.” Moe began as a nebulous term for anime and manga characters who are young, cute, and almost helpless, who inspire protective love in older characters. Some people interpret it in a sexual way, while others compare it to having an intense crush on a fictional character. (Lately the term has also been used as an alternative to “otaku” to express the intense love a fan can have for a property or character. Yay, language evolution!) In Clarisse’s case, her moe-ness is underlined by the fact that a wild, rakish older man is trying to protect her from being raped by an even older, even more dastardly man, but it’s undercut by the fact that she manages to fight for herself and rescue Lupin on a few occasions. She is portrayed as a young girl, just home from a convent school, and the count keeps her in a tower room fit for a fairy tale:

But she’s also bold enough to attempt escape, she stands up to the Count, and she risks her life for Lupin in a way not even Fujiko or Jigen have the guts to do. She lays the groundwork for later Miyazaki heroines like Nausicäa, Kiki, and Chihiro—naïve but plucky and good-hearted. This contrast between the two women leads to a larger theme that makes this film deceptively deep. Lupin is a great anti-hero, right? He risks life and limb to rescue a damsel from a horrific fate? Well, he does, but he also fails. Repeatedly. And when he does succeed, it’s for a very specific reason.

Lupin tries and fails to save Clarisse three separate times: First, during the car chase, he ends up taking the car off the cliff, but uses his handy rope contraption to stop their fall. Until the rope runs out, and they both fall to the beach below, he’s knocked unconscious, and Clarisse is re-kidnapped. Lupin is then rescued by Jigen. The next time he attempts rescue, the Count catches him in Clarisse’s room and drops him into a dungeon. He only survives the dungeon because he teams up with Zenigata. Finally, the Count catches him in Clarisse’s room a second time, and he and Clarisse only escape (momentarily) because Fujiko drops her disguise and lobs a bunch of grenades to cover them. Then the Count and his henchman shoot Lupin. He only survives because Clarisse shields him with her own body…

…which gives Fujiko just enough time to grab him and carry him to the autogyro.

Once they’re away, it’s Clarisse once again who grabs the muzzle of a burning hot machine gun to allow the autogyro to fly out of range.

After this attempt we finally learn why Lupin is so invested: a decade earlier, when Lupin was even more of a foolish punk than he is now….

…he tried to trace the origin of the “Goat” bills. He was one of the obsessives he told Jigen about, and he nearly died searching for the secret. So why didn’t he die?

Clarisse.

Tiny, eight-year-old Clarisse found him in her garden after he’d been shot with arrows. Rather than turning him in, she brought him water, and saved his life.

So we learn that his first failure is at the heart of this entire caper, driving him to repay Clarisse’s kindness. There’s another failure here, too, but I’ll get to that in a second.

Only after opening up and telling his friends the story does the tide turn for them. They all team up and concoct a scheme to crash the royal wedding, and finally, with Jigen and Goemon backing him up, and Fujiko and Zenigata acting as reinforcements, do they finally succeed in getting Clarisse away from the Count. Of course, he’s able to track them down so and Lupin can have a classic final showdown… but I think it’s significant that it’s only after Lupin drops what Jigen calls his “sad loner act” that they get anywhere. It’s also significant that even here at the climax, where usually the damsel waits on the sidelines gasping in dismay or yelling encouragement, Clarisse once again risks her life, throwing herself at the Count to try to pull him off the tower.

Lupin’s Decision

Now, for that other failure. Young Lupin was presented with true kindness, but rather than taking his near-death experience and Clarisse’s help as a wake-up call, he went right back to his life as a lascivious thief. Now, as a (slightly) more mature man, he has another choice. Clarisse offers to follow him into a life of larceny, and he thinks long and hard before turning her down. It’s a beautiful moment in a fairly silly film, especially since he even restricts himself to giving her a chaste peck on her forehead.

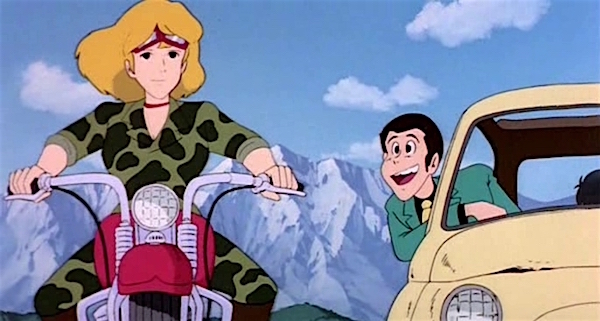

A few moments later, Jigen then offers the other solution: Lupin could stay behind, settle down with Clarisse, start a new life. For Jigen to bring this up is an astonishing departure—this is Lupin’s sharpshooting best friend, literal partner in crime. And Lupin seems to consider it. (I can only imagine the murmurs of shock in the theaters in 1979….) But then Fujiko pulls up on her bike and reveals her loot from Cagliostro: a complete set of counterfeiting plates. Lupin immediately shifts gears, howling after her, and cackling as he realizes Zenigata is in hot pursuit once again. Lupin’s storyline is reset in time for the next television season to begin.

Rejecting Clarisse’s offer was a great moment for Lupin, but you could read the next scene as another failure. Rather than growing up and leaving his ridiculous life for romantic love, he once again turns to crime, and his shallow, on-again-off-again pursuit of Fujiko. Of course this is also true to Lupin’s character, and it’s another way that Miyazaki ducks viewer expectations. When was the last time you watched a movie where a young woman risked her life for a dashing man, only for the two to end up apart? When have you ever seen the older man reject the young ingénue in favor of a more experienced, but also much more independent, lover?

Castle of Cagliostro isn’t just the best big screen foray of a beloved Japanese antihero—it’s also the All About Eve of anime.

Follow along with the Ghibli Rewatch as we delve into Hayao Miyazaki’s oeuvre!

Leah Schnelbach knows she’s not supposed to admire Lupin…but she kinda admires Lupin. Come plan heists with her on Twitter!

Way back in the ’90s, there was a local TV station that took advantage of FCC rules to show risque anime films after midnight (though still with the nudity posterized), but they also showed a lot of tamer anime, and I’m pretty sure that’s where I saw Castle of Cagliostro. I remember liking it quite a bit, and not being as impressed with a trio of Lupin III episodes I saw later. I’m not sure how many years later it was before I realized it had been a Miyazaki film. But I haven’t seen it in ages. Maybe I should revisit it.

I always liked Zenigata. Maybe for the same reason I always liked Jack McGee on The Incredible Hulk and Lt. Gerard in The Fugitive (the TV version, not the movie).

Oh man! A Ghibli rewatch! I am so in. Excellent article. Whenever I revisit this one I’m always a little startled about how dark it can get and how real the stakes seem, especially when half the time Lupin comes off like Bugs Bunny.

Is this going to be all of Ghibli as the name implies? Or just Miyazaki? I’m good either way, but I’d love to read an in depth analysis of Pom Poko.

We’re doing alllll of Ghibli! And I haven’t watched Pom Poko in years, so I’m especially excited for that one. :)

Now I’m wondering — could there have been any clock scene-based cross-pollination between ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas (the 1974 Rankin-Bass cartoon about a mouse who wrecks, and subsequently fixes, a clock) and Castle of Cagliostro? And/or between Night Before Christmas and Great Mouse Detective?

Oooh, I second what @@@@@ScavengerMonk said. Please make this series about the entire Ghibli catalogue, because there are some great films that aren’t Hayao Miyazaki’s.

edit: I posted this before I saw that you had responded, Leah. WOOT! As an aside, maybe this will get me to finally watch Tales from Earthsea, which I believe is the only Ghibli movie that I haven’t seen.

@hihosilver28 – Fair warning on Tales from Earthsea: It ain’t great.

I thought Earthsea would’ve been a tolerable generic fantasy movie if it didn’t share all of those character & place names from a fondly-remembered book series.

@4/hoopmanjh: I’m sure the trope of action scenes involving clock-tower gears is much older than any of the movies mentioned here. I’m pretty sure I’ve seen such a climax in some old black-and-white live-action comedy film, though I can’t remember what it was and Google keeps giving me Safety Last and Back to the Future when I try to look up movies involving clock-tower climaxes.

@@@@@ScavengerMonk

So I’ve heard, and is definitely a part of why I haven’t been in a rush to check it out. But I still feel like I should watch it. At this point in time, my least favorite Ghibli is “Only Yesterday”, which a bunch of other people loved, but just didn’t click with me or my wife.

@8 — Yes, now that you mention it, I’m certain I’ve seen something (Lloyd? Keaton?) along those lines.

8. @hoopmanjh

Well, for silent movies, you have Lloyd hanging off of a clock face in Safety Last, and then you have Chaplin going through gearworks in Modern Times, so both play off of that, but neither are really a climax inside of a clock tower.

I’m trying to wrack my brain as to what the first one is that I’ve seen, but I’m having trouble coming up with one.

@11 — Yes, I think Modern Times was the other clockwork scene I was thinking of after CLB’s response.

And just to drag things back to Lupin and Miyazaki, Discotek Media has released the full original series of Lupin (including episodes that I believe Miyazaki co-directed), and recently released a set containing the first 40 episodes of the second series (which I’m not sure include any Miyazaki involvement, although he apparently directed a couple of episodes much later in the series).

@11/12: I thought of Modern Times, but I have the impression I’ve seen something actually in the gears of a clock tower or something similar.

You know, come to think of it, the origin of the trope is probably windmills, not clock towers. I might be thinking of something like that, though I don’t think it was Frankenstein (1931).

There is an Orson Welles movie titled The Stranger – the ending involves a fight in a clock tower and Orson Welles dies after falling and being impaled on a piece of the clock mechanism

And let’s not forget about Cliff Hanger, the Dragon’s Lair-type laserdisc arcade game that was spliced together from this movie and another Lupin III film. At the time, we elementary-school kids had no idea we were playing through an anime classic.

Yay for the rewatch! Thanks so much for doing this, this is my fav Studio of all time!

I don’t know about anyone else, but I’ll probably get teary at every one of these movies I love them so much. Even this one made me tear up, as fun as it is.

@15/tls: Maybe my memory is all screwed up (that would be par for the course), but I have this impression of an older movie whose climax involved a stunt sequence with these huge gears turning and their teeth just barely avoiding crushing someone, and I was impressed with the daring of the actor/stunt performer for doing that. But I just can’t remember what movie it was or when it was from.

Although maybe that in itself proves that it’s a fairly widely used trope — I’ve seen it so many times in live action and animation that I probably have a bunch of different iterations mashed up in my memory. And I’ve never even seen The Great Mouse Detective, and though I probably saw the aforementioned Rankin-Bass Christmas movie when it aired in the ’70s, I have no memory of it.

@16/dwarzel I never could afford to play Cliff Hanger (it cost lots of money to get good at those laser disk games since you died so fast), but I watched a bunch of it one summer. Then a Japanese ex-roommate of one of my roommates left us a copy of the Castle of Cagliostro on tape when he graduated. Naturally in Japanese with no subtitles, so we had to watch it over and over again to figure out what on earth was going on. At some point later I got the Maurice Leblanc books from the library, in a further attempt to figure it out. Much easier nowadays :-)

I hadn’t realized Miyazaki had done Anne of Green Gables. Is that being sold anywhere?

It’s worth noting that the current Blu-ray release of Cagliostro is, literally, one of the best presentations of an anime on disc that I’ve ever seen. Not only does it have the original Japanese version, it also features both dubs, plus a revised version of the more recent dub cutting out nearly all of the obnoxious swearing Manga dropped in to try to make the title seem more risqué. (Who does that to a family-friendly Miyazaki movie? It’s like finger-painting all over the Mona Lisa.) There’s also a commentary track by renowned Lupin scholar Reed Nelson. And not only does it include a completely new subtitle translation, but it also throws in the bare-bones 1980s theatrical subs as a viewing option as well (in a font and color that comes as close as possible to their original appearance). Cagliostro has never looked or sounded this good.

(Meanwhile, I’m about 80% done with revising my own fan commentary for the movie, of which I released the first version over ten years ago. I’ve gotten the new version all written, now I just have to go back through and cut a few thousand words out so I don’t end up sounding like the Micro Machine Man when I record it…)

I can comment knowledgeably about this, because I was employed by Streamline Pictures at the time it licensed “Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro” from Tokyo Movie Shinsha in 1991 for release in the U.S. One of my assignments was to translate the script into English for the English-language dub on the VHS tape, released in October 1992. (It was released theatrically with subtitles by TMS in April 1991.)

A “professional criticism” that I got on the dubbing for the video, not from anyone in Streamline Pictures, was that there was too much “dead space” where there was no dialogue. I should have created dialogue to fill these up. These were the dialogue-less “quiet scenes” that Miyazaki had created, usually just before an action scene. I argued that we should just leave these exactly the way that Miyazaki had wanted. I didn’t have any trouble over this because Streamline’s president, Carl Macek, was also an opponent of what he called the “wall-to-wall dialogue” theory of dubbing; that you should never leave any quiet moments in an “animated cartoon”. At this time the Japanese animated features were considered to be just long animated cartoons, not real theatrical features.

I also argued for the title translation of “The Castle of Cagliostro” over “Cagliostro Castle”. The latter makes it just the name of a castle, while the former makes it the lair where the villain lurks.

I did lose one argument with Carl Macek. In one scene, Goemon follows a sword duel with the line, “I have again cut a worthless object.” It’s his catchphrase; he says it throughout the anime TV series. The Japanese audiences doubtlessly expected it. But Carl argued that the American audiences would be unfamiliar with it and it would only sound weird to them. He changed it to something like, “You should have worn a steel suit.” All the anime-fan purists were outraged that we hadn’t used a faithful translation.

Monkey Punch had high praise for “The Castle of Cagliosto”, while making it clear that Miyazaki’s Lupin III wasn’t his Lupin III. “I would have had Lupin rape the princess, not save her,” he joked.

The fan who showed the film at the Disney studio in 1981 was Mark Merlino, one of the founders of the Cartoon/Fantasy Organization, America’s first anime fan club in 1977. Merlino also showed the entire feature at the 1980 World S-F Convention in Boston, with TMS’ authorization. The Disney animators were particularly interested in the climactic duel in the clock tower. Which they based the climax of “The Great Mouse Detective” upon.

I love this movie. But the first time I saw it, I realized that it was the basis of an arcade game they had at the bowling alley when I was a kid (in the eighties).

@21/Fred Patten: Thanks, fascinating! That’s right, this was a TMS movie. I’ve long been a fan of their animation — in the sense of their actual technique, the quality and style of the work. One more reason to revisit the movie.

I’ve already spoken about this movie at great length, so I’ll settle for adding to this detailed article and the informative comments that follow it that 1980’s TMNT cartoon adapter and frequent scriptwriter David Wise confirmed to me via Twitter back in 2016 that Cagliostro’s Fujiko in disguise was indeed the inspiration for April O’Neil’s career and outfit.

As for the suit’s color: when I showed him a screengrab of Miyazaki’s Episode #155 (“Farewell, Beloved Lupin”, originally titled “Thieves Love Peace” by Miyazaki) where Fujiko has an even more similar yellow jumpsuit and a camcorder, he told me it wasn’t based on that version but instead the Cagliostro version. However, when he posted about this on his Facebook page on August 7, 2014, he used a screencap of Fujiko on her motorbike from #155 along with a camo-suit Fujiko statuette side-by-side with April to compare them (screencap). So really, who knows. He said in the same thread, “I first saw Miyazaki’s LUPIN work when I was in Japan in 1980. I’ve been swiping from his work longer than Pixar! :p” That episode aired in 1980, so who knows whether he only saw the Cagliostro version or both. Unfortunately his tweets in our discussion have since been deleted.

In April of 2016, Wise also confirmed the Cagliostro connection for his Batman: The Animated Series episode The Clock King. He initially tweeted (IIRC) that he’d been struggling with how to handle part of the script, and… “Then I remembered the clock tower fight at the end of Miyazaki’s CASTLE OF CAGLIOSTRO and I was like… ‘consider it done.'” (Source)

By the way, if you’re really going to re-watch all Miyazaki’s stuff, you ought to read The Incredible Tide by Alexander Key, then go through Miyazaki’s 26-episode Future Boy Conan based on it, which served as a sort of prototype for the sort of ecological themes he would explore again in his more famous work Nausicaa. It hasn’t been licensed by anyone (probably the animation style is too dated for studios to expect anyone to be interested, or perhaps there’s a rights issue surrounding the book it adapted) but it’s on YouTube.

It’s interesting to see the ways Miyazaki adapted this work by a fairly well-known western SF writer while at the same time giving it his own unique spin. Most notably, the book was written at the height of the Cold War, and in the book the good guys are Mom-and-apple-pie Americans and the bad guys are evil dirty commies. But at the time, Miyazaki was enamored of communism (he became disillusioned with it later, when the Soviet Union fell) so in his anime, the bad guys are capitalists run amok while the good guys are a farming commune.

@16 I remember playing an arcade game in a Pizza Hut manymanymany years ago that was based on Lupin III. At the time I had no idea what it was. I don’t remember the actual gameplay now.

The lack of official availability for the various TV series means they won’t get covered, but they are pretty good.

I’d note that Conan’s directed by Miyazaki, while on Heidi and Anne of Green Gables (and another one, 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother) he was assisting Isao Takahata. Their directorial styles seem further apart in these than later on — Conan’s an adventure caper in a similar vein to Cagliostro, which takes big cartoonish liberties with action sequences, while the Takahata shows are slice-of-life with realist action.

“means they won’t get covered”

Sorry — I should have said ‘probably means they won’t get covered’.

Wow, thank you for all these informative comments! Thank, Robotech_Master for the Blu-ray suggestion – I’m adding it to my wishlist – and thanks Reed Nelson for confirming the Fujiko/April O’Neill hypothesis! April was a great inspiration to a small, career-minded Leah, so the knowledge that Fujiko is basically her mom is fantastic. And Fred Patten, thank you for fighting for the quiet moments in the film. I noticed those scenes more on this watch, since I just re-watched a bunch of the television episodes as I prepped this piece. It really helps Miyazaki’s version of Lupin stand out as a more thoughtful character.

I might be able to cover Miyazaki and Takahata’s TV work a little bit (especially Future Boy Conan – I’ve never seen it and that synopsis sounds fascinating) but I think we are going to focus more on the movies, since they’re easier to access, and people can watch along. Speaking of which, next up is Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, so I hope you can all join me again! :)

I loved The Castle of Cagliostro, but what remains with me most strongly was the extreme vertigo it induced in me during the rooftop escape attempt, and the final fight on the clocktower. Miyazaki loves the sky, of course, and flight, and heights, and I’ve occasionally felt a little vertigo watching some of his other movies (some of the scenes in Laputa, for instance), but nothing like the dizziness I feel when I watch this movie. It’s worth it, though.

Also, do you think that the antagonist in Laputa might be as truly villainous as the Count in this movie? He seemed so to me. I’ll be interested in your thoughts when you get to that movie.

I’m surprised nobody has mentioned that there was a real Count di Cagliostro — though the resemblance more-or-less ends with the name.

@31 – That’s something that features prominently in my fan commentary track I’m currently working on recording. He was a prominent part of the history of France, and hence French author Maurice Leblanc (who had much the same taste for weaving real historical events and ancient conspiracies into his stories that Dan Brown does today) wrote a Lupin book involving one of his descendants. Which in turn meant the name was available for inspiration to Miyazaki, even though Castle of Cagliostro has very little to do with the actual historical figure.

Amusingly, the historical Cagliostro also inspired Marvel, who based a sorcerer character on him. That character wrote a mystical tome, the Book of Cagliostro, which was featured as an important maguffin in Marvel’s recent Doctor Strange movie (even though they pronounced its name wrong—a proper Italian pronunciation sounds more like “Collie-ostro”).

A Ghibli rewatch?! SQEEE.

@13: Miyazaki did direct two series II episodes, #155 (mentioned above) and #145, “Wings Of Death – Albatross”, which is just pure wonderful. I won’t spoil it here, because any description I provide won’t do it justice, but Fujiko gets to kick some serious butt in this episode. It left an indelible impression on my young mind when it saw it at a con c. 1980, and since then any female lead character I’ve written in my stories has at least a bit of Fujiko’s resourcefulness, cleverness, guff and/or sheer badassery in her.

For anyone who might be interested, I have finally completed Version 2 of my Castle of Cagliostro commentary track. You can find it here. Hope folks enjoy it!

Cagliostro really isn’t a departure at all from the style of storytelling in the show (part 1) up to that point. It’d always had the tendency to go surreal and fantastic at times, and many of the plot points and elements in the film were almost directly lifted from previous episodes of the show that Miyazaki and Takahata had directed. Also, I’d say that The Woman Called Fujiko Mine is still the best depiction/iteration of her character to date. She’s equal amounts sexy/manipulative and intelligent/tactful.

Also, Only Yesterday is the best Ghibli film. Shame a lot of people can’t see it’s genius.