Jim Shooter wrote the book that changed my life, the book that, I’m confident, landed me here. Here’s how it happened.

I’m twelve years old. We live way out in the country in West Texas, maybe fifteen miles east of Midland, an actual city—probably ninety thousand people then, thanks to the oil boom—but we’re not quite to Stanton, a little place of about three thousand. Stanton’s big compared to where we live, Greenwood. No post office, no mention on the map. Just a school and church on the same grounds, and lots of cotton fields, lots of pumpjacks, lots of pastures, and, every few miles, a house, a trailer out in the mesquite.

Every couple weeks, my mom would load me and my two little brothers up and we’d head into Midland, for groceries. It was a big event. Just shy of Midland, there was this gas station, Pecan Grove. We’d each get fifty or seventy-five cents and get to go in, buy a coke. Cokes were very rare in our lives.

One of those times—the Jim Shooter time—on the race back to the cooler for a Big Red or a Dr. Pepper, I saw something I hadn’t seen before.

Comic books.

A round rack of them.

Understand, in 1984, I’d never been to the theater to see a movie. All I knew about Star Wars was from a page I studied and studied in the JC Penney’s catalog I had to leave in the living room, because I’d stay up all night looking at it.

This is where things start for me, there in Pecan Grove. I’m staring at a comic book. I’m staring at the Incredible Hulk on the cover of issue 4 of Secret Wars. He’s green, even his hair. And, to save his friends, he’s holding up one hundred and fifty billions tons of rock.

I walk out of Pecan Grove without a coke, yes, and then over the next few months I’m always scrambling over my brothers to get to that round rack in Pecan Grove. I wouldn’t read Secret Wars in actual sequence until years later—the kids in the trailers behind Pecan Grove were probably nabbing the issues—but I was able to read a few of them.

Specifically, I was able to read issue 10. For me, for a long time, that’s where Secret Wars stops.

In the thirty-three years since that day I found the Hulk holding a mountain up, I’ve read thousands of books, thousands of comics, and they’ve all left their print on me, they’ve all left me a different person. But none so much as issue 10 of Secret Wars.

If you don’t know it, Secret Wars is all Earths’ mightiest heroes and villains getting spirited away to this Battle Planet for a sort of tournament of champions, so this omnipotent entity the Beyonder can watch them struggle, and perhaps understand this strange-to-him concept of “desire.” It makes for some cool fights, fun reversals, unexpected allies, character-changing developments, and of course lots of heroics and dark brooding—chief among the brooders is Doctor Doom.

Never content with the hand he’s dealt, Doom elects to try to change the nature of the game itself: he goes after the Beyonder, to steal his limitless power with a specially modified chest-plate, one that only works at about arm’s length.

This is an enterprise with no hope, of course. Not only is the Beyonder all-powerful, but Doom’s a bad guy, and bad guys don’t win, right?

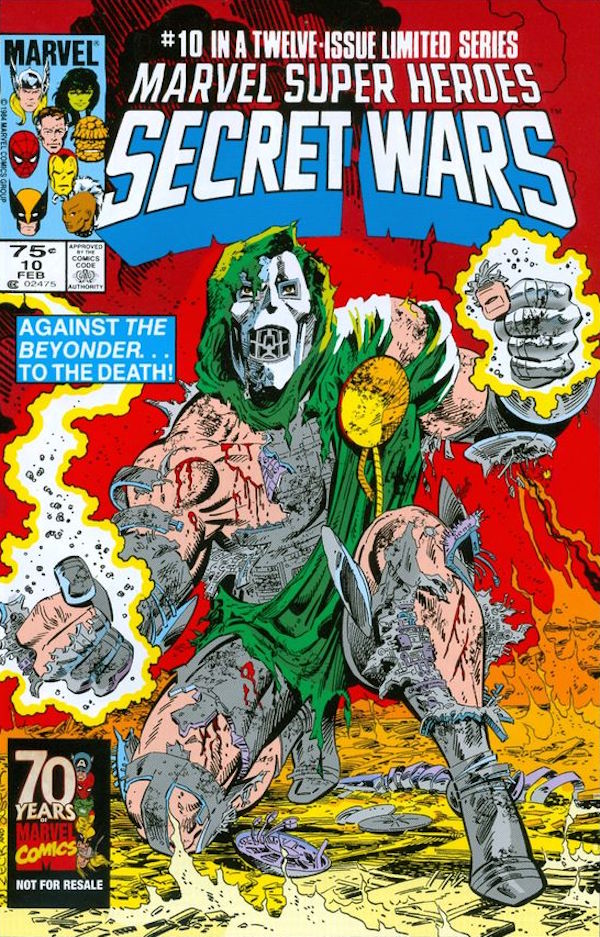

But look at that cover of issue 10.

Doom’s green tunic is in rags. His metal armor has been shredded away. He’s bleeding, he’s broken, he’s crackling and smoldering—this is what happens when you slog through wave after wave of energy hurled at you by an omnipotent being. This had to sell on the magazine rack, so the cover couldn’t show it, but one of Doom’s legs has even been burned off, and an arm would soon follow. There’s no way he can live, no way he can make it even one step closer to the Beyonder.

Yet he does. He’s Doom. “A way,” he says, “there must be—”

He’s hurt, he’s bleeding, he’s destroyed, this is impossible, this is stupid and crazy, but that doesn’t stop him. Then Beyonder, in all his vast innocence and naive curiosity, he draws close enough for Doom’s chest-plate to activate, and Doom, like that, steals the power infinite.

All because he wouldn’t give up.

All because he kept going.

That year, 1984, a lot of craziness started for our family, and left us moving all across Texas, just trying to stay together. A lot of bad situations. I was always the new kid at school. I was always having to prove myself on the playground, on the basketball court, in the parking lot, under the bleachers, in the principal’s office, in the back of cop cars, on a pumpjack, on a horse, under a hood.

But, each new hallway I walked into, each next job, each next whatever, I would set my eyes like Doctor Doom in issue 10, and I would tell myself that I would keep walking no matter what came at me, no matter the injury, no matter the chances, no matter the teachers standing me up in front of class as example to the rest, of somebody they should all look up when I was twenty, to see if I was still so funny.

I kept going. I kept insisting.

And yeah, I ran away into the pastures and the trees and the night and worse so many times, but I always came back. Because of Doom. Doom wouldn’t have given up. Doom would have insisted on seeing this hopeless enterprise through.

So I did too.

Secret Wars 10 didn’t turn me into a writer. Secret Wars 10, it kept me alive through all of my secret wars. Without it, there’s no me.

Thank you, Jim Shooter.

Stephen Graham Jones is the author of 22 or 23 books, 250+ stories, and all this stuff here. His horror novella, Mapping the Interior, is available now from Tor.com Publishing. He lives in Boulder, Colorado, and has a few broken-down old trucks, one PhD, and way too many boots.

Stephen Graham Jones is the author of 22 or 23 books, 250+ stories, and all this stuff here. His horror novella, Mapping the Interior, is available now from Tor.com Publishing. He lives in Boulder, Colorado, and has a few broken-down old trucks, one PhD, and way too many boots.