The Hobbit isn’t as good a book as The Lord of the Rings. It’s a children’s book, for one thing, and it talks down to the reader. It’s not quite set in Middle-earth—or if it is, then it isn’t quite set in the Third Age. It isn’t pegged down to history and geography the way The Lord of the Rings is. Most of all, it’s a first work by an immature writer; journeyman work and not the masterpiece he would later produce. But it’s still an excellent book. After all, it’s not much of a complaint to say that something isn’t as good as the best book in the world.

If you are fortunate enough to share a house with a bright six year old, or a seven or eight year old who still likes bedtime stories, I strongly recommend reading them a chapter of The Hobbit aloud every night before bed. It reads aloud brilliantly, and when you do this it’s quite clear that Tolkien intended it that way. I’ve read not only The Hobbit but The Lord of the Rings aloud twice, and had it read to me once. The sentences form the rhythms of speech, the pauses are in the right place, they fall well on the ear. This isn’t the case with a lot of books, even books I like. Many books were made to be read silently and fast. The other advantage of reading it aloud is that it allows you to read it even after you have it memorised and normal reading is difficult. It will also have the advantage that the child will encounter this early, so they won’t get the pap first and think that’s normal.

I first read The Hobbit when I was eight. I went on to read The Lord of the Rings immediately afterwards, with the words “Isn’t there another one of those around here?” What I liked about The Hobbit that first time through was the roster of adventures. It seemed to me a very good example of a kind of children’s book with which I was familiar—Narnia, of course, but also the whole set of children’s books in which children have magical adventures and come home safely. It didn’t occur to me that it had been written before a lot of them—I had no concept as a child that things were written in order and could influence each other. The Hobbit fit into a category with At the Back of the North Wind and The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and half of E. Nesbit.

The unusual thing about The Hobbit for me was that Bilbo Baggins was a hobbit and a grown up. He had his own charming and unusual house and he indulged in grown up pleasures like smoking and drinking. He didn’t have to evade his parents to go off on an adventure. He lived in a world where there were not only dwarves and elves and wizards but signs that said “Expert treasure hunter wants a good job, plenty of excitement and reasonable reward.” He lived a life a child could see as independent, with people coming to tea unexpectedly and with dishes to be done afterwards (this happened in our house all the time), but without any of the complicated adult disadvantages of jobs and romance. Bilbo didn’t want an adventure, but an adventure came and took him anyway. And it is “There and Back Again,” at the end he returns home with treasure and the gift of poetry.

Of course, The Lord of the Rings isn’t “another one of those.” Reading The Lord of the Rings immediately afterwards was like being thrown into deep magical water which I fortunately learned to breathe, but from which I have never truly emerged.

Reading The Hobbit now is odd. I can see all the patronizing asides, which were the sort of thing I found so familiar in children’s books that I’m sure they were quite invisible to me. I’ve read it many times between now and then, of course, including twice aloud, but while I know it extremely well I’ve never read it quite so obsessively that the words are carved in my DNA. I can find a paragraph I’d forgotten was there and think new thoughts when I’m reading it. That’s why I picked it up, though it wasn’t what I really wanted—but what I really wanted, I can’t read any more.

I notice all the differences between this world and the LOTR version of Middle-earth. I noticed how reluctant Tolkien is to name anything here—the Hill, the Water, the Great River, the Forest River, Lake Town, Dale—and this from the master namer. His names creep in around the edges—Gondolin, Moria, Esgaroth—but it’s as if he’s making a real effort to keep it linguistically simple. I find his using Anglo-Saxon runes instead of his own runes on the map unutterably sweet—he thought they’d be easier for children to read. (At eight, I couldn’t read either. At forty-five, I can read both.)

Now, my favourite part is the end, when things become morally complex. Then I don’t think I understood that properly. I understood Thorin’s greed for dragon gold—I’d read The Voyage of the Dawn Treader and I knew how that worked. What puzzled me was Bilbo’s use of the Arkenstone, which seemed treacherous, especially as it didn’t even work. Bilbo didn’t kill the dragon, and the introduction of Bard at that point in the story seemed unprecedentedly abrupt—I wonder why Tolkien didn’t introduce him earlier, in the Long Lake chapter? But it’s Bilbo’s information that allows the dragon to be killed, and that’s good enough for me, then or now.

Tolkien is wonderful at writing that hardest of all things to write well, the journey. It really feels as if he understands time and distance and landscape. Adventures come at just the right moments. Mirkwood remains atmospheric and marvellous. The geography comes in order that’s useful for the story, but it feels like real geography.

Noticing world differences, I’m appalled at how casually Bilbo uses the Ring, and surprised how little notice everyone else pays to it—as if such things are normal. Then it was just a magic ring, like the one in The Enchanted Castle. The stone giants—were they ents? They don’t seem quite ent-ish to me. What’s up with that? And Beorn doesn’t quite seem to fit anywhere either, with his performing animals and were-bearness.

The oddest thing about reading The Hobbit now is how (much more than The Lord of the Rings) it seems to be set in the fantasyland of roleplaying games. It’s a little quest, and the dwarves would have taken a hero if they could have found one, they make do with a burglar. There’s that sign. The encounters come just as they’re needed. Weapons and armour and magic items get picked up along the way. Kill the trolls, find a sword. Kill the dragon, find armour. Finish the adventure, get chests of gold and silver.

One more odd thing I noticed this time for the first time. Bilbo does his own washing up. He doesn’t have servants. Frodo has Sam, and Gaffer Gamgee, too. But while Bilbo is clearly comfortably off, he does his own cooking and baking and cleaning. This would have been unprededentedly eccentric for someone of his class in 1938. It’s also against gender stereotypes—Bilbo had made his own seedcakes, as why shouldn’t he, but in 1938 it was very unusual indeed for a man to bake. Bilbo isn’t a man, of course, he isn’t a middle class Englishman who would have had a housekeeper, he is a respectable hobbit. But I think because the world has changed to make not having servants and men cooking seem relatively normal we don’t notice that these choices must have been deliberate.

People often talk about how few women there are in LOTR. The Hobbit has none, absolutely none. I think the only mentions of women are Belladonna Took, Bilbo’s mother (dead before the story starts) Thorin’s sister, mother of Fili and Kili, and then Bilbo’s eventual nieces. We see no women on the page, elf, dwarf, human, or hobbit. But I didn’t miss them when I was eight and I don’t miss them now. I had no trouble identifying with Bilbo. This is a world without sex, except for misty reproductive purposes, and entirely without romance. Bilbo is such a bachelor that it doesn’t even need mentioning that he is—because Bilbo is in many ways a nominally adult child.

I think Bilbo is ambiguously gendered. He’s always referred to as “he,” but he keeps house and cooks, he isn’t brave except at a pinch—he’s brave without being at all macho, nor is his lack of machismo deprecated by the text, even when contrasted with the martial dwarves. Bilbo’s allowed to be afraid. He has whole rooms full of clothes. There’s a lot of the conventionally feminine in Bilbo, and there’s a reading here in which Bilbo is a timid houseproud cooking hostess who discovers more facets on an adventure. (I’m sure I could do something with the buttons popping off too if I tried hard enough.) Unlike most heroes, it really wouldn’t change Bilbo at all if you changed his pronoun. Now isn’t that an interesting thought to go rushing off behind without even a pocket handkerchief?

This article was originally published in September 2010.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published a collection of Tor.com pieces, three poetry collections and thirteen novels, including the Hugo and Nebula winning Among Others. Her most recent book is Thessaly. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here irregularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

When I started The Hobbit…on the recommendation of a family friend…I really disliked Bilbo.

Rather than being amused by the arrival of the Dwarves and the supper scene, I was merely uncomfortable; rather than being intrigued by the discovery of the Ring, I was disoriented and annoyed by Bilbo’s subsequent dishonesties; rather than being sympathetic with his weaknesses, I was embarrassed. I was so close to putting the book down many times . . . all the way through up to Bilbo being the one to “discover” the keyhole. Somehow his simple act of logical realization put me solidly on his side, so that throughout the suspense of his talk with Smaug, his morally questionable choice to remove the Arkenstone, and his nonexistent part in the battle, I was now utterly engaged. I read through to the end and immediately opened FotR fully expecting to continue my adventures with Bilbo.

When I realized Bilbo would not be the protagonist in this extension of The Hobbit (as I thought), I almost put it down and didn’t continue! Whew! What I would have missed!

I think that at one point Tolkien contemplated rewriting The Hobbit to bring it more in line with LotR (above & beyond the famous Riddles in the Dark revision, that is). I’m kind of glad he didn’t; I find it perfectly charming.

Having said which, there’s part of me that has to regard it as not entirely literal — it feels like Bilbo lightly fictionalizing his adventures and turning them into a children’s story; so maybe the stone giants (arguably the least necessary part of Peter Jackson’s films, well, except maybe for the Sandworms of Middle-Earth) weren’t actually literal?

I do not dispute the greater point about the lack of women, but I’ve got to shout out to Lobelia Sackville-Baggins, whom I’ve always enjoyed seeing far more than I ought.

“If you are fortunate enough to share a house with a bright six year old, or a seven or eight year old who still likes bedtime stories”

For what it’s worth, we read Lord of the Rings to our boy starting around the time he turned seven — took us four or five months, but it was and I think still is his favorite book. I believe we read him the Hobbit twice before that, so when he was five or six. He just turned nine, still gets a bedtime story every night, and last week asked me to start Lord of the Rings over again.

You’re absolutely right that they read aloud beautifully.

I was quite shocked by the opening of this piece. Writing a successful children’s book is surely at least as difficult as writing a successful adult novel. And as a children’s book I suggest it is very successful. Certainly, having ploughed through the Narnia series, The Hobbit was a breath of fresh air (and I share JRRT’s dislike of allegory). Nesbit is I suggest rather different and brings magic into everyday life rather than writing “straight” fantasy. Certainly I can reread The Hobbit now (along with Wind in the Willows) with great pleasure still – not so Narnia. And I suggest that this is because Tolkien does not actually talk down to his readers; while the prose is simple the issues (loyalty, war and peace, honesty and deceit etc.) are complex ones. The Arkenstone is central to this debate – a treasure which can be fought over or used to bring peace (and is there not an echo of this in LOTR when an elven brooch is dropped as a marker and there is a comment (from Aragorn) to the effect that a treasure that cannot be cast aside at need is worthless – I am sorry but I do not have the text immediately to hand). And of course the One Ring itself…….

Tolkien totally does talk down to his readers. He doesn’t do it all the time, but The Hobbit is full of direct asides. Tolkien himself later in a letter repudiates this and wishes he hadn’t done it, they get fewer as the book goes on and LOTR doesn’t have any of it.

I agree that writing a children’s book is a worthy and excellent thing to do, but it’s inherently going to be less satisfying for adults than an equally excellent adult book. And an adult book is going to be less satisfying for children.

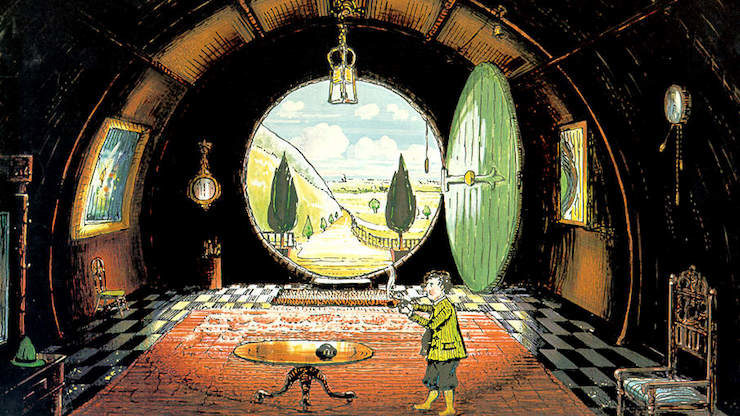

Going by the lead illustration, the first difficulty that Bilbo would have had to overcome when setting off on any adventure would be finding some way to reach the doorknob on his front door. Why is this never mentioned?

I love LotR. Yet I love The Hobbit more. On a windy winter night it is the perfect companion. Give me that book, an armchair, a woodstove and a whisky at my elbow and I forget everything but the story for a few hours. Escapist? Isn’t that the point?

One more odd thing I noticed this time for the first time. Bilbo does his own washing up. He doesn’t have servants. Frodo has Sam, and Gaffer Gamgee, too. But while Bilbo is clearly comfortably off, he does his own cooking and baking and cleaning.

Sam isn’t really Frodo’s servant, in the sense of a live-in full-time employee who does housework. He’s his gardener. Frodo, like Bilbo, does all his own cooking and cleaning and so on, and lives alone. Sam doesn’t even seem to be full-time.

And I think this is not just an eccentricity, but central to the whole plot of both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

Hobbits don’t have servants. They don’t really even seem to have employees, at least not in the Shire (there are hobbit employees in Bree, working at the Prancing Pony and presumably elsewhere, but no hobbit employers as far as we know; the Prancing Pony is run by a human). And while there are rich and poor hobbits, we never see hobbits who want to get rich (or if we do it’s very un-hobbit-like of them). There aren’t any hobbit entrepreneurs or merchants.

Because hobbits, unlike humans, don’t lust for power over others. That’s why the Ring is safe with them and that’s probably why the Ring ends up with hobbits at all; safest place for it. Bilbo can be trusted with the One Ring because he bakes his own cake and washes his own dishes.

Tolkien is wonderful at writing that hardest of all things to write well, the journey. It really feels as if he understands time and distance and landscape. Adventures come at just the right moments. Mirkwood remains atmospheric and marvellous. The geography comes in order that’s useful for the story, but it feels like real geography.

Ha! Only last month on this very site there was someone loftily explaining that Tolkien didn’t really understand logistics and roads and geography…https://www.tor.com/2017/08/24/epic-fantasy-and-breaking-the-rules-of-infrastructure-in-the-interest-of-speed/

I don’t think it was unusual in 1938 for a middle-class man without female companionship or a daily housekeeper to cook and wash up for himself. I think it was unusual in 1938 for a middle-class man to have neither female companionship nor a daily housekeeper.

“The Diary of a Nobody” is a good few years before The Hobbit, but not too many to be a model. Charles Pooter is a “nobody”, that is, as humble as is possible short of being actually (ugh!) working class. He rents his house rather than owns it. But he has a wife, and employs one live-in servant and one daily housekeeper.

But once Tolkien had decided for the purposes of the story that Bilbo was to be living on his own, the rest follows, and would not have raised any eyebrows; he would simply have been understood as that which is now used as a sly euphemism for gay… a confirmed bachelor.

I think some of Tolkien’s sight gags and asides were intended as a satire on modern Thirties life. He has a dig at golf if I remember, and “Bag End” is a translation, into the language of English place names, of the French phrase used for a type of suburban housing development popular around that time: cul-de-sac.

This kind of development was particularly in the popular mind in places like “Metro-land”, the expansion of commuter housing out into the county of Middlesex by the Metropolitan Railway company from the 1920s onwards. Exactly the kind of thing that would have horrified Tolkien, paving his country paradise and putting up a parking lot.

I am intrigued by the insight that Bilbo could have had his gender changed and it wouldn’t have affected the story.

I will defend Jackson for one moment (and then beat myself with a stick in penance) regarding the Sandworms of Middle-Earth. Let me quote from Chapter 1 “An Unexpected Party:”

“Tell me what you want done, and I will try it, if I have to walk from here to the East of East and fight the wild Were-Worms in the Last Desert.“

Perhaps the only thing he got right…

Ajay — I didn’t say he understood logistics etc, (though I wouldn’t be able to tell the difference whether he did or not) I said he made the journey bits fun to read and seem real and interesting. I can imagine a book written by somebody who understood all those things perfectly and got them utterly correct but who should instead have written “Ten days later when we arrived in X” because making journeys effective for the reader is hard. Though in fact I think Tolkien, who regularly went off for long hikes in England and the Welsh borders, understood walking pace and walking and weather but maybe not carrying provisions because he was never more than five miles from a pub!

“The Diary of a Nobody” is a good few years before The Hobbit, but not too many to be a model.

It’s quite a few years earlier! It was published fifty years before The Hobbit. A lot happened to British society between 1888 and 1938. Someone of Pooter’s status in 1938 almost certainly would not have had a live-in servant. If single, he might have had a landlady (if he was living in rented rooms); if married, he would have had a “daily” – a servant who lived out but came in a few days a week. 1930s novelists like Dorothy Sayers are probably a better guide here…

@9 – this may be what you are referring to with the ‘un hobbit like’ but wasn’t pimple face Lotho an example of somebody trying to ‘modernize’ and basically start business in the Shire (and get rich)? Anyway. Your point is taken :)

My son is 6 and we recently read The Hobbit as a bedtime story. He enjoyed it quite a bit, especially Gandalf (he even caught right away that the voice getting the trolls to fight was Gandalf and was very excited by this). We’ve watched bits and pieces of the movie (Peter Jackson that is) but it’s a bit too long to keep his attention (the first one that is, never mind the other two).

Have to agree that the were worms actually ARE a part of the lore. In my opinion the most needless addition is all the Bolg/Azog/Ravenhill/Thorin/Legolas nonsense.

There’s nothing in the text to suggest that Bilbo didn’t have someone come in occasionally for things like laundry (which he could also have sent out) or major cleaning. And given the nature of hobbits, it’s entirely possible that cooking and baking are considered acceptable pastimes for a gentlehobbit, just as drawing or music were for British gentlemen. (That’s a total retcon, of course, but it’s my headcanon and I’m sticking to it.)

And given the nature of hobbits, it’s entirely possible that cooking and baking are considered acceptable pastimes for a gentlehobbit, just as drawing or music were for British gentlemen.

That is a very convincing headcanon. Asking a hobbit “but why do you cook for yourself, when you could afford to pay someone else to do it” would probably have been like asking an Edwardian squire “but you employ a gamekeeper; isn’t it his job to hunt foxes, not yours?” The squire lived in a society that above all valued cavalry skills like courage and good horsemanship; of course he hunted. Hobbits value good food and hospitality and good living. Cooking your own food is the point. (Though it’s a thoughtful gesture to help with the washing up.)

There’s nothing in the text to suggest that Bilbo didn’t have someone come in occasionally for things like laundry (which he could also have sent out) or major cleaning.

Quite. But that’s not really having a servant, who you can just order around; that’s buying a service from another free hobbit. In my headcanon, Gammer Gamgee (wife of Gaffer, mother of Samwise) took in the laundry for both Mr Bagginses, placing special emphasis on ensuring an uninterrupted supply of pocket-handkerchiefs.

this may be what you are referring to with the ‘un hobbit like’ but wasn’t pimple face Lotho an example of somebody trying to ‘modernize’ and basically start business in the Shire (and get rich)?

Yes indeed. And doing it under the malign influence of the spirit of destructive modernisation, Saruman himself. Very un-hobbit-like!

Ha. The lack of romance in The Hobbit‘s world didn’t stop me from loving Gollum, though this love didn’t become mind-stealing adoration until I read LotR at 16.

As a kid, I didn’t think much about where Bilbo’s food came from and whether all his own cooking or, for example, bought his seedcakes from a hobbit bakery. The former makes some sense, as described above, but it’s never fully explained. Some fantasy stories have relatively realistic and well-described food systems, others just don’t, and I think Tolkien’s work is among the latter, though not the most extreme example.

I read The Hobbit countless times as a kid and more-or-less memorized it. But I missed a lot of its depth, as I learned recently from listening to Point North Media’s entertaining and insightful There And Back Again podcast series, which I’m gonna keep promoting because it says a lot of relevant things. It attributes the Shire’s ambiguity of food systems and general logistics to the fact that “Tolkien didn’t care about economics,” but calls the Shire’s social structure a quite deliberate portrait of Tolkien’s ideal society — a low-tech feudal community of benevolent gentry and virtuous, contented laborers, where people can’t change their station in life and rarely try, where rich and poor can care about each other without treating each other as equals. E.g. Frodo and Sam are the closest of friends but also Master and Servant, even when very far from home. Bad Things happen when hobbits like the miller (user of the most advanced local technology) try to get richer and gentry prioritize wealth over responsibility. Or something like that; TABA hasn’t reached the end of RotK and won’t for a very long time.

I always assumed the “stone giants” were real in The Hobbit despite having no mention or place in LotR. Something Tolkien thought of but then had no further use for and tried to pretend didn’t happen. I was surprised to learne that some readers believe them to have ben metaphorical all along.

@19: I may be the only one who wanted to treat the stone giants as metaphorical. Your explanation (“Something Tolkien thought of but then had no further use for and tried to pretend didn’t happen”) is probably the correct one. Wonder if he felt the same way about pocket watches …

(And your explanation also puts me in mind of J.K. Rowling — there’s a whole bunch of stuff especially in the first Harry Potter book that feels like it was put in there just to be kind of fun and whimsical, and which then has to be accounted for in all of the future books, even when they’re taking a much more serious tone.)

When I was first in the Coast Guard, I used to read the Hobbit to my little brothers whenever I was home. But one day after a long absence, when I said, “Lets read the last two chapters tonight,” my brothers said, “You don’t need to, we finished it ourselves.” The pesky little guys had learned how to read, and taken the bull by the horns.

“All hobbits, of course, can cook, for they begin to learn the art before their letters (which many never reach); but Sam was a good cook, even by hobbit reckoning […]” — The Two Towers

Confirmation that for hobbits, cooking ability and inclination are not related to gender or class.

Right. But that was a choice on Tolkien’s part, and a choice that was a departure from the norms and expectations of his own society.

@15

That’s quite a negative reaction, given that I pretty much nailed it. Pooter is married, and does have a daily woman in. The only difference is that he also has an unskilled girl boarding in the spare room.

Anyway, the more you say servants were rarer in the Thirties, the more you make my point, which was that men only stayed out of the kitchen to the extent they had women in the house. If they didn’t, then they didn’t. It wasn’t rare for a single man alone in the house to be doing the dishes, it was just rare to be a single man alone in the house. It’s not because of B that p(A∩B) has a low probability: p(B|A) is actually quite high. And the readers are ready to accept that.

Let me put it another way: hardly anyone is a street sweeper, and if your novel starts “At a crossroads in the middle of town there worked a sweeper,” you might say “huh, odd choice of protagonist”. But once you accept that part, it should come as no surprise when the author puts a broom in his hand.

Tolkien doesn’t want the children reading the book to be wondering how the arrival of a wizard and twice seven dwarves puts the cook out of temper, he wants you focussing on how their intrusion upends the comfortable life of Bilbo specifically, whose person and house he sets up in the first sentence and elaborates in the paragraph that follows.

I also disagree that a man who does the dishes, or a woman who changes the light bulb, is gender ambiguous. They’re just single. Can you imagine Aragorn, or Lymond, not doing the dishes, if they were to be done and there was no one else to do it? You might think of them doing it all manly and ranger-like with a bit of sand in the river, but I suggest that they’d do it in a house just as readily. They just don’t because there’s someone else to handle that. (spoilers: this is a plot point in Queen’s Play, even)

I would point out it’s not reviewers from 1938-1988 that are boggling at this, it’s reviewers from 1988-2038, with their odd ideas of Thirties society: but see the Clark Gable film It Happened One Night, or read the positively Heinleinesque novella it was based on, “Bus Stop”.

@9 Ajay: you say, “Bilbo can be trusted with the One Ring BECAUSE he bakes his own cake and washes his own dishes.”

Nailed it!

[from Jo Walton’s article] “But I think because the world has changed to make not having servants and men cooking seem relatively normal we don’t notice that these choices must have been deliberate.”

This is a remarkable observation. There are comparably deliberate choices in LOTR as well, so far unnoticed. Coded phrase, slyly inserted by the Master.