James Blish was a popular science fiction writer and critic who began his literary career while still in his mid-teens. Not yet out of high school, Blish created his own science fiction fanzine, and shortly thereafter became an early member of the Futurians, a society of science fiction fans, many of whom went on to become well-known writers and editors. From the ’40s to the ’70s, Blish submitted a slew of fascinating tales to a variety of pulp magazines, including Future, Astounding Science Fiction, Galaxy Science Fiction, The Magazine of Science Fiction and Fantasy, and Worlds of If, just to name a handful. Although Blish’s most widely recognized contribution to the science fiction genre may be his novelizations of the original 1960s Star Trek episodes (to which his talented wife Judith Lawrence contributed), his magnum opus is undoubtedly the numerous “Okie” tales written over the span of a decade and merged together into the four-volume series known as Cities in Flight.

To give you some background, it was in 1991, when I entered Junior High School—a brave new world indeed—that I first discovered James Blish. For it was then, to celebrate Star Trek’s 25th anniversary, that Blish’s adaptations were compiled in three thick paperback volumes, each containing a full season’s worth of episodes. As I recall, the first book, which collected season one, was purple; the second was red, and the third was blue. I purchased the first two volumes at SmithBooks in the summer of 1992. I enjoyed them immensely; I read and reread them repeatedly, never tiring of them. (I finally managed to snag the third—in pristine condition, to my delight—at a used bookstore a decade later.) And the extra insights and background exposition by Blish, however perfunctory or limited (which in many respects, they were) made me feel as though I actually knew the characters personally.

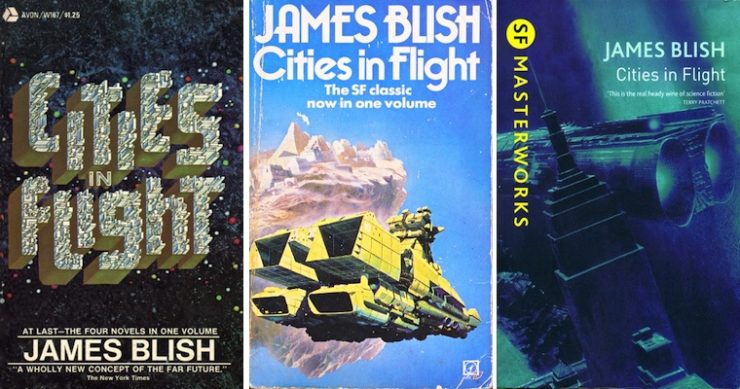

After reading these novelizations in the early ‘90s, I set out to find other science fiction works by Blish. Recognizing that he was an author from before my time, and a prolific one, I decided that my best bet would be to check out used bookstores, which were more than likely to carry at least a modest selection of his books. I was right, as it turned out, and took the opportunity to pick up a couple of other novels by Blish: VOR (a story of the first time an alien being crash lands on Earth, and then insists that it wishes to die) and Jack of Eagles (a tale about an ordinary American man who discovers he has enhanced psionic powers). Both of these relatively short novels are intriguing in their own right. It was also at a used bookstore that I first came across the Cities in Flight omnibus—although I confess that upon initial perusal it looked very formidable to my fourteen-year-old eyes.

ABOUT JAMES BLISH

James Blish, born in 1921 in East Orange, New Jersey, was a gifted writer of science fiction and fantasy. As mentioned above, his interest in these genres began early. At the age of fifteen, Blish began to publish The Planeteer, a monthly science fiction fanzine he both edited and contributed to from November 1935 to April 1936. For each issue, Blish penned a science fiction tale: Neptunian Refuge (Nov. 1935); Mad Vision (Dec. 1935); Pursuit into Nowhere (Jan. 1936); Threat from Copernicus (Feb. 1936); Trail of the Comet (Mar. 1936); and Bat-Shadow Shroud (Apr. 1936). In the late 1930s, Blish joined the Futurians, a body of sci-fi writers and editors based in New York City who significantly influenced the development of the sci-fi genre between 1937 and 1945. Other members included sci-fi giants Isaac Asimov and Frederik Pohl.

James Blish, born in 1921 in East Orange, New Jersey, was a gifted writer of science fiction and fantasy. As mentioned above, his interest in these genres began early. At the age of fifteen, Blish began to publish The Planeteer, a monthly science fiction fanzine he both edited and contributed to from November 1935 to April 1936. For each issue, Blish penned a science fiction tale: Neptunian Refuge (Nov. 1935); Mad Vision (Dec. 1935); Pursuit into Nowhere (Jan. 1936); Threat from Copernicus (Feb. 1936); Trail of the Comet (Mar. 1936); and Bat-Shadow Shroud (Apr. 1936). In the late 1930s, Blish joined the Futurians, a body of sci-fi writers and editors based in New York City who significantly influenced the development of the sci-fi genre between 1937 and 1945. Other members included sci-fi giants Isaac Asimov and Frederik Pohl.

Blish’s first published story, Emergency Refueling, appeared in the March 1940 issue of Super Science Stories, a pulp magazine. Throughout the 1940s, such magazines were the main venue in which his stories saw print. It was between 1950 and 1962, however, that Blish published his crowning achievement, the Cities in Flight tetralogy. In 1959, Blish won the Hugo Award for Best Novel for A Case of Conscience, and was nominated in 1970 for We All Die Naked. He was also nominated for the Nebula Award on three occasions: in 1965 for The Shipwrecked Hotel, in 1968 for Black Easter, and 1970 for A Style in Treason. Also in 1970, Avon Books collected the four Cities in Flight novels and rereleased them together, for the first time, in one hefty volume.

The very commercially successful Star Trek novelizations of the original 1960s television episodes that remain Blish’s best-known work were released over a ten-year period—from 1967 to 1977—in twelve slim volumes, each with multiple printings to accommodate the widespread demand. In addition to these popular, highly-readable short stories, he also wrote the first original adult Star Trek novel, Spock Must Die!, which was released in February 1970 by Bantam Books, one year after the original television series was—to the dismay of loyal viewers—canceled by NBC. And although it was not widely known to the general public, Blish also used the pseudonym William Atheling, Jr. to write critical science fiction articles, as well.

As a final note, I thought it apt to include an interesting fact about Blish: In 1952, he originated the term “gas giant” to describe immense gaseous planets when he altered the descriptive text of his 1941 tale Solar Plexus. The relevant passage reads: “… a magnetic field of some strength nearby, one that didn’t belong to the invisible gas giant revolving half a million miles away.”

THE EPIC: CITIES IN FLIGHT

Cities in Flight, Blish’s galaxy-spanning masterpiece, was initially published as four separate books well over a half-century ago. It should be noted, however, that the four original books were not written in sequential order. According to James Blish, “The volumes were written roughly in the order III, I, IV, [and] II over a period of fifteen years…”

The first novel, They Shall Have Stars, was published in 1956; the second, A Life for the Stars, was published in 1962; the third, Earthman, Come Home, was published in 1955; and the fourth, The Triumph of Time, was published in 1958. Finally, in 1970 the “Okie” novels, as they were dubbed thereafter, were skillfully woven into a single epic-length tale and published in an omnibus edition as Cities in Flight.

The stories which compose the Cities in Flight saga were inspired by the Great Migration of “Okies” (a colloquial and unflattering appellation for rural Americans from Oklahoma) to California in the 1930s due to the Dust Bowl. The latter is a term referring to the intense dust storms—so-called “black blizzards”—that devastated farmland in the Great Plains during the Great Depression. And to some extent, Blish was influenced by Oswald Spengler’s major philosophical work, The Decline of the West, which posited that history is not divided into epochal segments but cultures—Egyptian, Chinese, Indian, etc.—each lasting approximately two millenia. These cultures, Spengler averred, were like living beings, who thrive for a time and then gradually wither away.

Cities in Flight tells the story of the Okies, albeit in a futuristic context. These Earthmen and women are migrants who voyage through space while living in enormous, detached cities capable of interstellar flight. The purpose of these nomadic folk is rather prosaic—they are driven to search for work and a viable lifestyle due to the worldwide economic stagnation. Powerful anti-gravity machines known as “spindizzies,” built into the bottommost layer of these city-structures, propel them through space at post-light speed. The result is that the cities are self-contained; oxygen is trapped inside an airtight bubble of sorts, which harmful cosmic material cannot penetrate.

Blish’s space opera is tremendous in its scope. The full saga unfolds over several thousand years, features many ingenious technological marvels, and stars dozens of key protagonists and many alien races who are confronted by ongoing predicaments that they must overcome through ingenuity and perseverance. The story vividly conveys both Blish’s political leanings and his disdain for the present condition of life in the West. For instance, Blish’s loathing of McCarthyism—which was then at full steam—is evident, and in his dystopian vision, the FBI has evolved into a repressive, Gestapo-like organization. Politically, the Soviet system and the Cold War still exist, at least in the first installment, although the Western government has done away with so many personal freedoms as to render the Western social order a mirror of its Soviet counterpart.

They Shall Have Stars is the first of the four novels. Here, the far reaches of our own solar system have been fully explored. However, mankind’s desire to proceed even further into the unknown is made possible through two vital discoveries: one, anti-aging drugs which allow the user to prevent senescence; and two, anti-gravity devices that facilitate galactic travel. Hundreds of years have elapsed by the time of A Life for the Stars, the second installment, and mankind has developed sufficiently advanced technology to permit Earth’s largest cities to break away from the Earth itself and set off into space. The third novel, Earthman, Come Home, is related from the viewpoint of centuries-old New York mayor John Amalfi. The societal changes resulting from centuries in galactic transit have not been favorable; by this time, the space-roaming cities have regressed to a savage, chaotic state, and these renegade societies now endanger other enlightened offworld civilizations.

The last of the four novels, The Triumph of Time, continues from Amalfi’s perspective. The New York city-in-flight is now passing through the Greater Magellanic Cloud (a dwarf galaxy some fifty kiloparsecs from the Milky Way), although a new threat of galactic proportions is impending: a cataclysmic collision of matter and anti-matter that will destroy the universe. This is known as the Big Crunch, a theoretical scenario in which it is hypothesized that the universe will eventually contract and collapse in on itself due to extraordinarily high density and cosmic temperatures—the reverse of the Big Bang. If interpreted in religious terms, the ending parallels the beginning of the Old Testament’s Book of Genesis—or rather, presents its inescapable opposite.

Truth be told, Blish’s space epic is a rather pessimistic conception of mankind’s future. And although it is undeniably dated by today’s standards—some amusing references to obsolete technology are made (slide rules, vacuum tubes, etc.)— present-day readers will still appreciate the quality of the literature and, as a benchmark example of hard science fiction, find it a memorable read.

A FINAL RECOMMENDATION

For a generous sample of James Blish’s finest work spanning a three decade-long career, I personally recommend The Best of James Blish (1979), which I recently acquired online. It is a carefully selected collection of short stories, novelettes, and novellas, which in the opinion of some readers, including my own, tend to surpass some of his lengthier works. For convenience, here is a list of its contents: Science Fiction the Hard Way (Introduction by Robert A. W. Lowndes); Citadel of Thought, 1941; The Box, 1949; There Shall Be No Darkness, 1950; Surface Tension, 1956 (revision from Sunken Universe, 1942 and Surface Tension, 1952);Testament of Andros, 1953; Common Time, 1953; Beep, 1954; A Work of Art, 1956; This Earth of Hours, 1959;The Oath, 1960; How Beautiful with Banners, 1966; A Style in Treason, 1970 (expansion from A Hero’s Life, 1966); and Probapossible Prolegomena to Ideareal History (Afterward by William Atheling, Jr., 1978).

Thomas Xavier Ferenczi is a man of diverse background. Born in Edmonton, Alberta, he has studied management, pharmacology, and law. As an author, he has written a science fiction screenplay, Extraterrestrial, and his most recent project is a techno-thriller, Conspiracy. He is also a writer in many other genres, including legal and historical non-fiction. He has a particular affinity for the science fiction tales of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A bookworm, he can often be found in a coffeeshop, diner, or pub with his nose buried deep in a novel or textbook. He currently resides in Western Canada.

I found this series a great read as a curiosity piece. The lead-in image originally appeared in “Alien Landscapes”, an SFF art book from the 1970s that featured some pretty amazing original images of several fictional locales (Hothouse, Mesklin, Pern, Arrakis, Rama, Eros, Trantor …)

Thank you for this article. I enjoyed Blish’s Trek novelizations when I was about the same age as you, and around the same exact time. Matter of fact, it would be long before I actually got to see TOS for real, as my contact with Star Trek was with the TOS crew films, and then TNG.

I should definitely track down some of Blish’s original work, I don’t know why I haven’t. Perhaps I’ll start with The Best Of volume.

I read the Cities in Flight omnibus seven years ago, and I have to say, I was underwhelmed by it. The only part I really liked was the prologue, They Shall Have Stars. There’s some very nice writing in it, witty and creative uses of language. It’s very much a product of its time, and interesting as a historical artifact — although, sadly, its prediction of a dystopian, authoritarian US government feels much less quaint today than it did in 2011.

I was less impressed by A Life for the Stars. The young protagonist just kept stumbling into greater success and status to a degree that makes Kirk’s promotion in the 2009 Star Trek movie seem slow-paced. And there isn’t even any real action. The protagonist gets peripherally involved in dangerous situations, other characters go off and do the big, important stuff, and then they come back and tell him how they followed his advice and saved the day.

Also, for a book about cities flying through space, ALftS didn’t do a very good job of depicting the rather wild and intriguing concept of New York City flying through space. There’s barely any reference to New York’s geography, aside from mentioning at the end that the mayor’s control center is atop the Empire State Building. It doesn’t feel like New York. It just feels like a generic sci-fi setting. Maybe that’s because Blish had already covered the NYC geography elements in Earthman, Come Home.

I can’t say I enjoyed Earthman all that much either. I didn’t care for the blatant amorality of the characters. I can get that they’re basically galactic hoboes and have to do what they must to survive, but they’d be more sympathetic characters if they had some ethical qualms and weren’t quite so ruthless in their scheming. And the “He” section contains some truly horrific misogyny that made me reluctant to keep reading. The Hevians see women as evil animals and keep them naked and caged, and the first thing they do is to give away a bunch of their women — seemingly hundreds — to the New Yorkers, who don’t seem bothered by the Hevians’ misogyny. When New York needs to get away from the pirate city, they take these hundreds of naked animal-women and leave them for the pirates as a distraction, not caring what kind of violation or abuse or slavery may befall them. But it’s a moot point, since literally minutes after the women are taken aboard the pirate city, it’s destroyed as a consequence of the New Yorkers’ escape plan. All those helpless women are killed, it’s the protagonists’ fault, and nobody cares in the slightest, not even the token female lead (who herself has a habit of inappropriate casual nudism). I’ve seen plenty of misogyny from classic SF protagonists, but never anything that casually, genocidally dehumanizing toward women.

As for The Triumph of Time, it felt like an afterthought. The saga pretty much ended with Earthman, Come Home, and having the characters suddenly have to tackle the end of the universe, and be the only ones in the universe in a position to do anything about it, however tenuously, was out of left field and an implausible aggrandizement of the characters. The whole thing seemed rather unfocused, really, and I wasn’t crazy about where some of the characters’ journeys took them.

Throughout the series, Blish never really put any effort into depicting aliens. A few alien species, mainly the Vegans, were discussed here and there and occasionally emerged as actors in the story, but they were always unseen, off-camera, and never developed in any degree. So the attempt to establish a new alien menace, the Web of Hercules, in The Triumph of Time is superficial and unsatisfying. They’re supposedly the main danger in the novel, but they’re an afterthought; once they finally show up, they’re quite literally defeated with the press of a single button. It’s a terribly weak ending to the saga, all the more so in contrast to the cosmic scale it strives for.

Granted, the books did have their points of interest, and they certainly had their share of ideas. One thing I have to give Blish credit for is his futurism. He even seems to have predicted nanotechnology, because he writes about drugs and materials engineered on a molecular level. And the telepresence system used on the Bridge in They Shall Have Stars presages virtual reality. (Yet on the other hand, the super-advanced technology of two millennia hence is still based on vacuum tubes.)

@1/cecrow: I used to have Alien Landscapes! I recognized the top image as being from that book — which was my first exposure to the concept of the Okie Cities, as well as some of the others you mention — but I’d forgotten its title.

I have that omnibus with the Harris cover from the top image. I wonder what I would think of the books on a reread; would the striking images be subsumed by the “Spengler-in-space” structure? A Case of Conscience is arguably the essential Blish novel; the start of the science fictional strand which led to The Sparrow and The Book of Strange New Things.

I read these as a kid in the 60’s (the paperback on the left was the one I had) and I loved them. I especially loved the ending. The Free Planet of He made frequent appearances in our role-playing games in the mid-70’s. Ah, nostalgia!

<i>Also, for a book about cities flying through space, ALftS didn’t do a very good job of depicting the rather wild and intriguing concept of New York City flying through space. There’s barely any reference to New York’s geography, aside from mentioning at the end that the mayor’s control center is atop the Empire State Building. It doesn’t feel like New York. It just feels like a generic sci-fi setting.</i>

I am realizing that I read the four novels in an omnibus edition, so I’m not dead sure of which bits of atmosphere were in in which books. But while there’s not a whole lot of local color, as a NY kid I found the bits there were very engaging — e.g., the 23d street spindizzy is the one that’s always going bad; the control room is at least at one point on the top floor of City Hall (Empire State in another book?). But I think you did have to be really alert to pick up the crumbs of locality there are.

While I wasn’t crazy about the books, I think you could get a pretty cool movie out of the concept of New York City launching into space and wandering the universe. You could film it on location in Manhattan (though it would have to be nearer-future than the books for that to work) and get some pretty nifty visuals out of the city soaring through the galaxy, encountering alien spaceships, etc.

(Re: the author photo.) Blish is more dapper than I’d envisioned him.

I read the four books about 15 years ago and, like Mr. Bennett, I wasn’t too impressed. My beef is with the worldbuilding, or lack thereof: New York City becomes an Okie centuries in our future, and yet the few narrative clues are that it’s architecturally the same as 20cen, the time of writing. It’s populated by millions(?) of people, many of them immorbid, and yet there’s no reference to any local culture created during the city’s soujourns between the stars — art, music, theatre, future art-forms, horticulture. It’s like they twiddle their thumbs, waiting for the City Fathers (the boxcar-sized semi-mobile computers in the cellar) to find a new job. (Maybe this made more thematic sense at the time of writing? The historical Okies and hobos didn’t do much beyond bare survival.)

Influence of the stories: In the anime Space Battleship Yamato 2 (1978), Gatlantis (a.k.a. the White Comet Empire) is depicted as a spacegoing city of towers atop a hemispherical, cratered base — like half a moonlet, or a scooped-out portion of planetary crust. It makes planetfall in the ocean near Japan, then returns to space.

The late Paul Kantner of Jefferson Airplane and Jefferson Starship was a huge fan of Blish and of the Okie series in particular. When the Starship album Blows Against the Empire (back when they still sounded somewhat like the Airplane, rather than trying to imitate Foreigner) came out, he said that it had been influenced by the Okie books.

I read the Avon omnibus when it was published and it doesn’t seem to have made much of an impression on me since I don’t remember much about it. I do still remember very clearly Blish’s Black Easter, which I read serialized in Worlds of If in 1967. That and its sequel The Day After Judgement (Galaxy 1970) remain my favorite works by him. A Case of Conscience, which I read as an SFBC edition probably in the mid ’60s, is also really good. Somehow I never read his other religious/occult work, Dr. Mirabilis which apparently has some connection to Black Easter, The Day After Judgement & A Case of Conscience. That didn’t get a US paperback edition until 1982, which may account for me missing it.

@3:

Have to agree with you on a lot of points. I too read the leftmost omnibus when I was in high school (long time ago, now). It had its moments, and I’ve never been able to forget the concept of the spindizzy – why did nobody ever pick this up and do more with it? However, Blish seemed to ignore problems with time and scale selectively – crossing the Rift is an epic journey, but at other times New York seems to ping-pong around interstellar space without much concern for relative distances. The rise and fall of civilizations doesn’t appear to be associated with, well, with anything, really. Currency is suddenly backed by anti-agathic drugs, with no really good reason given (and all over the Galaxy, all at once?). And the repair facility for flying cities has one guy in a coverall manning the office, and he’s armed with a revolver he doesn’t know how to use.

@5:

A Case of Conscience, together with the Black Easter duology and Doctor Mirabilis, were a thematic trilogy collectively known as After Such Knowledge, in which Blish examined the morality of inquiry (I believe that his answer was given by John the Beggar near the end of Dr. Mirabilis – why isn’t this book better-known?)

” In the late 1930s, Blish joined the Futurians, a body of sci-fi writers and editors based in New York City who significantly influenced the development of the sci-fi genre between 1937 and 1945.”

That makes it seems like the Futurians were almost a proto-SFWA. Which they were not. It was a club of teenaged fans of whom many became writers and/or editors.

The Wiki entry is good: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Futurians

As is this from the Fancyclopedia: http://fancyclopedia.org/futurians

My first taste of Blish remains my favourite – Surface Tension. Came across it in an old tattered copy of “The Science Fiction Hall of Fame” in a friend’s hostel room. I liked Cities in Flight well enough, but it did not give me the same feeling of awe and delight that Surface tension did, and the last part, Triumph of Time, was frankly boring (I can remember precisely nothing of it now). For that matter even the other Pantropy stories were nowhere near as enjoyable as Surface Tension, for me at any rate.

Yes, Cities in Flight definitely belongs on that list we had last week of “Great ideas badly executed”. Because there are some terrific directions that this idea could go. Flying cities! Here’s a list of story concepts none of which Blish thought about really:

— What happens to the places they leave behind? Manhattan Island tears itself loose of the surly bonds of Earth and goes off to wander the cosmos; what happens to Long Island? What happens to the US once it loses its 100 biggest cities? Is the US government going to try to stop them leaving?

— Cities aren’t self sufficient. How do they feed themselves? What happens when those systems start to break down? Come to that, how does a city that has always drawn in newcomers to live and work manage when that supply of new citizens is choked off?

— How does the inequality in a modern city work with a setup where everyone has to depend on everyone else or die in vacuum?

— Do the City Fathers have their own agenda? What’s in it for them?

— Did everyone want to leave? Is there a faction that would want to go back? Have any cities gone back to Earth ever, and what happened when they did?

— The cities seem to work as mobile industrial bases; they land on a foreign planet and trade for manufactured goods. Well, that sounds great until they want to leave; I wouldn’t want my industrial base to just float away suddenly. What happens then?

— What happens if Manhattan lands somewhere nice and half its population decide they’d quite like to go and live in the country?

— The cities fight offstage but we never see it. What does that look like?

For a four-book series, it left a lot of ground uncovered…

Such harsh comments! Just have to chime in and say how much I enjoyed reading the books when I was a teenager many moons again, and how it fired my imagination.

I loved that book as a teenager. I had the version with the first cover. It had the same effect on me then that the Culture had in later years.

@14 That does not strike me as much of a problem. If you need to get everyone working towards a common goal, a common organisation and hierarchy, and therefore inequality, seem to be quite common. A common danger may lead to a different form of inequality, but it does not often lead to LESS inequality. Pretty much every country in the world today in less unequal than it was a century or two ago, when life was more dangerous. Likewise, ships, mines, oil rigs and so on are rarely seen as bastions of equality. The common danger produces hierarchy and inequality.

I have to agree with the other points, though.

The concept of New York City launching itself into space is not without a certain appeal to the rest of the US.

@13 Thanks for mentioning Surface Tension; that was my favorite Blish work.

And, since our TV could not pull in an NBC station, his ‘novelizations’ of Star Trek episodes were my first exposure to the show; I eagerly snapped them up as quickly as they appeared (although perhaps ‘short-story-ization’ would be a more accurate term for the process).

I was not a big fan of the Cities in Flight series; I never bought into the premise because I could never suspend my disbelief when it came to the spindizzies. Because I remembered reading some Cities in Flight tales in shorter form, I poked around the internet a bit, and found out that the novels were indeed ‘fix-ups’ that included previously published material.

I’d agree that the books collected in Cities in Flight stand below the novels of After Such Knowledge and the best of Blish’s short fiction. But I’m bemused at some of the comments above. For one thing, Blish told the stories that he told for the reasons that he told them. Could he have told others? Sure. That’s always true of a writer telling stories. It’s not usually a valid criticism of the stories that were actually told. (The personnel issues were dealt with in some detail in the second and third book, too, so it’s not clear to me where that criticism comes from.)

The thing about these stories that makes them great and that also makes them awful is that they’re Blish’s attempt at “intensively recomplicated” fiction. He made up the word, as a critic, for A.E. Van Vogt’s preposterous yet strangely wonderful thud-and-blunder space epics. That’s why, especially in the stories collected in Earthman Come Home, characters are always trying to be wilier than some other wily character and the hero always finds a way to pull a rabbit or smeerp out of his hat in the last couple pages.

Blish was also trying to write an “evolutionary series” (that is, one where each installment changed the characters and their world irrevocably) as opposed to a “template series” (where you know Captain Future and the Futuremen will be back next month, doing pretty much the same ridiculous things). To make this work, he used Otto Spengler’s cyclical theory of history to shape his history of the future. I kind of see this as a handcuffed magician trying to escape from a straightjacket while immersed in a tank of water with a padlocked lid–maybe too many tricks are being attempted at once there, Houdini.

A lot of the social attitudes are retrograde, or just odd. (You can’t have a civilization in a jungle, apparently. Why not is not clear.) The technology is often amusingly out of date as well. And the history is wrong: like lots of his contemporaries, Blish assumed that the Cold War would last indefinitely (ending with a final victory for the Soviet Union). That makes his year 2018 very different from ours.

But there is some serious material here (especially his corrosive pessimisim about democracy), and some serious fun of the demented Van-Vogtian type.

You can’t have a civilization in the jungle? Tell that to the Maya. And everybody in the sixties believed the USSR was permanent and would likely win out in the end. Opinions on whether this was a bad thing varied.

@21/roxana: I don’t think the jungle grew over the Maya’s territory until after their civilization fell. On the other hand, there was a pretty rich civilization in the South American rainforest; a lot of what was long assumed to be natural wilderness was actually the result of centuries of arboriculture and selective breeding of rainforest plants to serve human needs, which is why there are so many beneficial and useful plants there. Conventional agriculture would’ve led to the soil being quickly washed away in that climate, so they had to cultivate and modify the existing forest instead.

Yes, I thought of the Amazon dwellers too. The Maya hacked back the jungle just like they did.

One problem with maintaining a civilization in the jungle is that jungles tend to grow in poor soil meaning that establishing and maintaining sufficient agricultural base is difficult.

I suppose Brooklyn, Queens, and maybe The Bronx are out flying around the galaxy too. I’m not so sure about Staten Island.

@23/roxana: No, my point was that the Amazon dwellers didn’t “hack back the jungle,” because, as you say, doing so would’ve caused the heavy rains to wash away the soil and left the land too barren for agriculture. So they had to work with the rainforest, breed the trees and other existing plants to be more useful to humans, rather than tearing them down and planting conventional crops. They also developed a form of artificial soil called terra preta, mixing charcoal, bone, and manure into the soil to increase its fertility. It’s only in recent years that we’ve begun to understand this and to realize that the pre-Columbian Amazon Basin was far more densely populated than has conventionally been assumed. This is discussed in Charles C. Mann’s book 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, which I recommend.

Sorry, I meant to say that the Maya hacked back the jungle in the traditional slash and burn method. That should have been an unlike.

Blish’s attitudes about jungles were probably a relic of colonialism. There’s a lot of that going around in midcentury sf. But it’s really not true that everybody in the 60s (or the 50s, which is more to the point) thought the USSR would win the Cold War. Asimov envisioned a future where the world was permanently divided between Us and Them (“Let’s Get Together”, 1957). Heinlein envisioned a future where the Soviet Union and its allies were defeated in WWIII during the 1960s (The Door into Summer, 1957). Brackett (The Long Tomorrow, 1956) and many another envisioned a “no one wins” scenario where civilization is attempting a comeback after a nuclear war. And so on. In general, generalizations that begin “everyone thought” can be hard to defend.

@27/James: I agree that not everyone thought the USSR would win the Cold War, but few writers predicted how early its fall would be. Star Trek presumed world peace in the 23rd century, but also had Chekov reference Leningrad, and in TNG’s second episode, the Tsiolkovsky‘s dedication plaque said it was built in “Baikonur Cosmodrome, USSR, Earth.”

And Blish didn’t portray the USSR as winning, technically; rather, in his version, the US became equally totalitarian, so that ideology won out even though the conflict between the two nations endured. Kind of the opposite of the Trek version, where the USSR survives but the American ideology wins out.

@19/Alan Brown — That sounds very similar to my experience: None of the three local broadcast stations (and yes, that’s ALL WE HAD; well, plus the PBS station) were showing syndicated Star Trek reruns, so I had to console myself with the Blish Star Trek Log books. Which, whatever else you may say about them, had some really great covers.

@29/hoopmanjh: The Star Trek Log series was Alan Dean Foster’s novelizations of the animated series. Blish’s (and J.A. Lawrence’s) adaptations were just Star Trek 1-12, plus Lawrence’s Mudd’s Angels (later retitled Mudd’s Enterprise in reprint) adapting the Harry Mudd episodes and adding a (really terrible) original sequel story.

@27 Christopher L. Bennett: I agree that there’s a variety of opinion in 1950s sf (and afterwards) about how the Cold War would play out. RAH, who saw a victory through military conflict, was an outlier (and was as wrong, in his way, as everyone else was in theirs). But in Blish’s future history the USSR does end up winning. It’s foreseen in They Shall Have Stars, and is part of the background of books 2-4.

e.g.

“At this time an attempt was made to settle the rivalry between the two power blocs by still another personal pact between their respective leaders, President MacHinery of the Western Common Market and Premier Erdsenov of the USSR. This took place in 2022, and the subsequent Cold Peace provided little incentive for space flight. In 2027 MacHinery was assassinated, and Erdsenov proclaimed himself premier and president of a United Earth.” (Chapter 4, A Life for the Stars)

Nowadays we would laugh at the idea of the USA coming under Russian influence in the first quarter of the 21st century, but there was a time when this unlikely event seemed somewhat possible. #IlaughthatImaynotweep

@30/CLB — I stand corrected. I did also read a few of the Foster volumes, but not many — I was limited to what they had at the public library.

I stand by my comment about the cover art, though.

That totally looks like a Blish space city.