In Episode 9 of After Trek, the roundtable talk show that airs after Star Trek: Discovery, Executive Producer Aaron Harberts said, “Everything we do on Star Trek comes out of character, and also as much as we can ground in science, so, shameless plug: get [the real-life mycelium expert and scientist] Paul Stamets’ book Mycelium Running. Give it a read…[it] will give you very, very good hints as to what’s going to happen.” So I did.

I bought the book, which is essentially a textbook for growing and interacting with mycelium and mushrooms, and I read it. I’d say I read it so you don’t have to, but the truth is: it’s a brilliant work of science, and everyone should give it a shot, especially if you’re a layperson like me. In addition to learning how to grow mushrooms from my one-bedroom New York City apartment (which I am enthusiastically now doing, by the way), I also learned a ton about Star Trek: Discovery’s past, present, and possible future.

Much like mycelium branches out and connects varieties of plant life, I will use Mycelium Running to join Star Trek: Discovery to its underlying science. Fair warning: this post shall be spoiler-filled, for those of you who have yet to finish the first season of Star Trek: Discovery. As I alluded earlier, I am no scientist, and I welcome scientific corrections of any kind from those who have done more than buy a lone book and earn a “Gentleman’s D” in undergrad Biology years ago. Also, what follows are my observations and mine alone, and are not meant to represent confirmed links between Star Trek: Discovery and 21st century Stamets’ research. Finally, hereafter, “Paul Stamets” will refer to the real-life, 2018 Paul Stamets, unless otherwise noted.

All right, let’s talk about mycelium.

According to Paul Stamets, thin, cobweb-like mycelium “runs through virtually all habitats…unlocking nutritional sources stored in plants and other organisms, building soils” (Stamets 1). Mycelium fruits mushrooms. Mushrooms produce spores. Spores produce more mushrooms. If you’ve been watching Star Trek: Discovery, you probably stopped on the word “spores.” Spores are used as the “fuel” that drives the U.S.S. Discovery. But how?

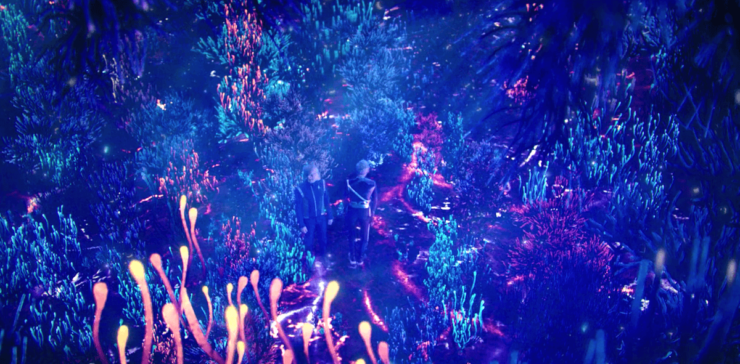

In Paul Stamets’ TED Talk, we learn that mycelium converts cellulose into fungal sugars, which means ethanol. Ethanol can then be used as a fuel source. But that’s not what the spores do on the Discovery. There, they link the ship into an intergalactic mycelial network which can zap the vessel virtually anywhere they’ve plotted a course to. This could be considered a logical extrapolation from Paul Stamets’ work. As Stamets states in Mycelium Running, “I believe mycelium operates at a level of complexity that exceeds the computational powers of our most advanced supercomputers” (Stamets 7). From there, Stamets posits that mycelium could allow inter-species communication and data relay about the movements of organisms all around the planet. In other words, mycelium is nature’s Internet. Thus, it is not too far of a leap for sci-fi writers to suggest that a ship, properly built, could hitch a ride on that network and direct itself to a destination at a rate comparable to that of an email’s time between sender and recipient, regardless of distance. Both the U.S.S. Discovery’s and the Mirror Universe’s I.S.S. Charon’s spore technology demonstrate what this could possibly look like.

While these suppositions are theoretical by today’s standards, much has already been proven about mycelium, mushrooms, and their spores, and a great deal of that science could appear in future seasons of Star Trek: Discovery. From Stamets, we learn that mushrooms, developing out of mycelium, have great rehabilitative properties. They restore blighted land. In Stamets’ words, “…if a toxin contaminates a habitat, mushrooms often appear that not only tolerate the toxin, but also metabolize it as a nutrient or cause it to decompose” (Stamets 57). This means that, if an oil spill occurs on a piece of land, meticulous placement of mycelium could produce mushrooms there that would consume the spilled oil and convert the land into fertile ground. What’s more, the sprouting mushrooms could neutralize the toxicity of the oil by “digesting” it, meaning those mushrooms could be eaten with no ill effects felt by their consumers.

Star Trek: Discovery creates two opportunities for this science-based function to appear in Season 2. In the episodes “Vaulting Ambition” and “What’s Past Is Prologue,” we learn that Mirror Paul Stamets (Anthony Rapp) has infected the mycelial network with a disease or corruption that seems to be spreading. Scientifically speaking, the cure for this might just be more mycelium, which could consume the infection and revitalize growth in an act of bioremediation. This would create a “mycofilter” capable of restoring health (Stamets 68). Such a crop could already be growing on the planet the Discovery‘s Paul Stamets terraformed in “The War Without, The War Within.” As a brief aside, I was struck by the process Discovery’s Paul Stamets used to terraform that planet, specifically the rapid, powerful pulses applied to the planet’s surface after sporulation. This is wonderfully reminiscent of an old Japanese Shiitake mushroom-growing method called “soak and strike,” in which logs were immersed in water and then “violently hit…to induce fruiting,” pictured below (Stamets 141).

If one application of mycelium-based rehabilitation is the repair of the network itself, another possible use may be the healing of Mirror Lorca. While much speculation, currently, investigates the possible whereabouts of Prime Lorca, Paul Stamets has made me wonder if Star Trek‘s mycelium could repair a human body. It’s not that much of a sci-fi reach. A specific kind of fungus called “chaga” has been known to repair trees in just this way. Stamets writes, “When [Mycologist Jim Gouin] made a poultice of ground chaga and packed it into the lesions of infected chestnut trees, the wounds healed over and the trees recovered free of blight” (Stamets 33). Fungus, it is important to note, contains mycelium. Since Mirror Lorca fell into a reactor made of contained mycelium, one wonders if he didn’t integrate into the network, and, if so, if the network couldn’t act as chaga did on the aforementioned chestnut trees. This would take a great deal of incubation, perhaps, but there’s a possible host for that, too: Tilly. At the end of “What’s Past Is Prologue,” a single green dot of mycelium lands on Tilly and is absorbed into her. If this mycelium also contains the biological footprint of Mirror Lorca, his mycelial rehabilitation could be happening inside of her. Of course, one may desire such a restoration for Culber, but that seems far less likely as he (a) did not “die” by falling into mycelium and (b) seems to have died with enough closure for us to accept finality. But Stamets is quite clear about this: mushrooms are nature’s mediator between life and death. The implications this statement has for science fiction stories, especially Star Trek: Discovery, are vast. Indeed, these speculations are not directly linked to the science Stamets writes about, but they are exactly the sort of extensions science fiction writers might utilize to tell great Star Trek tales.

Given that mycelium is, as Stamets says, “a fusion between a stomach and a brain,” its roles in the Star Trek universe will surely be defined by “eating” (disease, death itself) or thinking (plotting courses, providing data) (Stamets 125). As mycelium works in nature, though, organisms are attracted to the products of its labor. Mushrooms draw myriad insects and animals who feast on insects. Therefore, the insertion of a (very large) tardigrade early on in Star Trek: Discovery‘s run makes sense. It potentially formed the same symbiotic relationship Earth’s organisms foster with mycelium and mushrooms: the insects receive nourishment, and, in some cases anyway, the insects assist with spore transport. This opens the door for Season 2 to explore more species that might be pulled toward the cosmic mycelial network seeking a similar relationship.

The better we understand mycelium, the better we understand the ethical questions posed by the spore drive. Mycelium is aware of the organisms that interact with it. Stamets notes in his TED Talk, that, when you step on mycelium in the forest, it reacts to your foot by slowly reaching up toward it. The largest organism in the world, Stamets suggests, may have been the 2,400-acre contiguous growth of mycelium that once existed in eastern Oregon (Stamets 49). If the future accepts mycelial networks as sentient, their use as forced ship-drivers could be seen as a form of abuse or, at worst, enslavement of an organism. This may help to explain why Starfleet ultimately abandons the spore drive. That, and the gnarly effects spore drive experimentation had on the crew of the U.S.S. Glenn in “Context Is For Kings.”

Star Trek is at its best when it’s fueled by a healthy blend of science and suspension of disbelief. When the foundational science is solid enough, we’re willing to take it a couple of steps further into the future, chasing a great sci-fi story. By reading Paul Stamets’ Mycelium Running, I learned some of the very real, fascinating science that spurred the writerly imagination we see materialize in Star Trek: Discovery—and, I have to say, I’m totally on board for it. This first season of Discovery not only succeeded in incorporating cutting-edge, 21st century science into its vision of the future, but seems to be building on that science in ways that could inform the show’s plot and character arcs, going forward. To quote Cadet Tilly talking to Rapp’s echo of today’s star mycologist, “You guys, this is so fucking cool.”

Note: all in-text citations came from Paul Stamets’ Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save The World from Ten Speed Press, copyright 2005.

Jonathan Alexandratos is a playwright and essayist whose work largely revolves around action figures and grief. The fungus that is Jonathan can be found @jalexan on Twitter.

“Thus, it is not too far of a leap for sci-fi writers to suggest that a ship, properly built, could hitch a ride on that network and direct itself to a destination”

It may work as metaphor, but how can a starship ride a protein around the universe?

The idea is nice, but rather than turn the metaphor into something that could actually work faster than the speed of light, they seem to have just taken the terminology wholesale and put it in the vacuum of space, where if things move at the speed of say an organic molecule percolating through blood, they are gonna take a million years to get anywhere.

Yep it’s not hard to make something up:

“…how can a starship ride a protein around the universe?”

– “At some stage the mycelial network evolved to incorporate dark matter as a substrate, which allowed it to spread between multiversal branes. Using the network to travel involves manipulating spores to excite reactions that open wormholes along the mycelial threads, linking the source and intended destination in this or other universes.”

– “OK but why is there a huge water bear and why is everyone given to such over-the-top turns of phrase and sweaty flashbacks?”

– “Shrooms. Do I need to paint you a picture?”

Thank you for reading the book for us, but I have a comment, and a question.

Comment: The mycelium doesn’t plot courses, that was the stardigrade, or Stamets with its DNA infused into his.

Question: How well supported by other scientists are REAL LIFE Paul Stamets’ claims in this book?

It’s an okay metaphor, but tying this whizbang new form of travel so closely to a topping on pizza makes it hard to swallow. As I’ve seen it pointed out elsewhere, it’s like an astrophysicist studying oranges to understand how stars work. They’re both round and orange. Micro and macro, they must be the same thing!

Then again, this is the franchise that gave us an enormous space amoeba. A fantastic voyage, you might say.

Oh God. More magic mushrooms!

@1/ash: They did eventually explain that the specific species of fungus that forms the cosmic mycelial network exists partly in subspace and partly in normal space. It’s a fanciful idea, but we’ve seen subspace life forms before in Trek, like the solanogen-based subspace life forms in TNG: “Schisms” and the interspatial parasites in ENT: “Twilight” (indeed, the “interspatial” part implies they exist simultaneously in different spatial domains, like the mycelial network does). So as silly as it is in real-world terms, it does have Trek-universe precedent.

As best I can understand it, the displacement-activated spore hub drive (which nobody ever calls DASH drive for some reason, even though the name was obviously coined to generate that acronym) taps into the mycelial network’s quantum entanglement to let it scan and navigate to any destination through the mycelial plane, the subspace domain where the network grows. So it’s still traveling through subspace like a warp-driven ship, but the mycelium gives it the ability to quantum-leap to anywhere in the network, because of the network’s “knowledge” of all its parts. Although the quantum probabilities are so complex that computers can’t handle them, which is why they couldn’t use the drive to travel any distance until they acquired the tardigrade-like alien, a life form that had evolved in symbiosis with the network and was able to navigate it.

By the way, it just struck me: The taxonomic name of the subspace fungus is Prototaxites stellaviatori. The species name is from the Latin for “star” and “traveler,” so it basically means “Prototaxites Star Trekker.”

@3: I agree with you about the Tardigrade plotting courses, but, by the end, it seemed like there was an onboard way to plot courses along the mycelial network using a ship interface to “tell” Stamets’ infused self where to go. That’s what it seemed like when Lorca plugged in some coordinates to the MU from his chair.

To your question, though: The work seems fairly well supported to me. I’d be interested to know more about this, though, from a scientist’s perspective. Dr. Andrew Weil has done a lot of work in this field, too, and comes up quite a bit in the book. Some other studies are cited, too, plus an array of government contracts to expand Stamets’ work (an endorsement, of sorts?). Ancient Chinese medicine comes up quite a bit, too, and usually provides Stamets with historical grounding for some of what he says. That said, if a career scientist said, “Hey, I actually need to see more to really believe this,” I’d totally listen to that. I should also say that I have not read any of Stamets’ scientific papers. The goal of Mycelium Running seems to be to introduce the layperson to the art and science of growing and caring for mushrooms, so may be less interested in scientific citations on the level of peer-reviewed journals.

@1 A physical starship couldn’t, but maybe a modified warp field bubble could (which might be what touched off the idea of using it in a drive in the first place). The ship doesn’t so much “travel” through the network as it dematerializes and rematerializes after being “conducted” through the network like an electrical charge through copper wiring. The spore drive basically treats the mycelial network like a transporter beam.

For that matter, maybe (future) Stamets’ work serves as the basis for Scotty’s work in long-range teleportation.

@8/Cybersnark: “For that matter, maybe (future) Stamets’ work serves as the basis for Scotty’s work in long-range teleportation.”

I’ll never understand why people assume that Scotty had to invent long-range transporters. We’ve seen multiple types of interstellar transporter used throughout the Trek franchise — in “The Gamesters of Triskelion,” “Assignment: Earth,” and “That Which Survives” in TOS, “Allegiance” and “Bloodlines” in TNG, “The Jem’Hadar” in DS9, and “Displaced” in VGR. “Bloodlines” established that they were already a known technology as of 2370, but were rarely used due to the power demands and the risks involved.

@6 – Chris: Nice one about the name.

@7 – Jonathan: True, there seems to be a hybrid system of sorts. Thanks for the answer on the question.

So, this will make it even tougher to reconcile the existence of an organic subspace network that no other Trek series references. Okay then.

@3. Magnus: “Question: How well supported by other scientists are REAL LIFE Paul Stamets’ claims in this book?”

We need to ask a more specific question than that. Which is: How do any astrophysicists view claims of an organic network in space. Answer: pure nonsense.

RealStamets’ work and reputation in his field is not the issue. Applying it to another discipline and saying “it is not too far of a leap for sci-fi writers to suggest that a ship, properly built, could hitch a ride on that network” is a huge leap. Which is fine in a work of imagination. But it’s still hilarious. I may have to watch season 2 while I’m high.

Speaking of which: @CLB: ” Although the quantum probabilities are so complex that computers can’t handle them…”

Sure, if you posit a network the size of multiverses, it will exceed computational powers of computers. But it will exceed human brains too, not to mention giant space waterbears. This is all sounding more like using the Navigators of Dune to help heighliner engines jump from point to point without materializing in a planet or star. The Navigators get high on spice to expand their consciousness, just as InShowStamets gets high on magic mushrooms to pilot the ship.

Now, if you were positing a mycelial network that took over a planet and made it fully conscious, as in Gaia theory, it’d buy that. But this all makes me shake my head for the fate of season 2.

Uh, does this mean that subspace isn’t like space at all, but more akin to a very, very large, huge, immense planetary surface? With the equivalent of soil and organic matter and all that? Could we grow food there?

@12. Jana: yes, it will be a magic fairyland with plentiful ‘shrooms. And it will raise the dead… the glowy green will o’ the wisp is Culber.

@11 – Sunspear: But I was not asking that question regarding the space fungus network, because that’s soft science fiction, or even space fantasy.

But I wanted to know how valid is Stamets’ work. If we can then use it as basis for some entertaining fiction, then that’s a bonus.

@11/Sunspear: The notion of sentient consciousness having properties beyond what computers are capable of has a lot of precedent in science fiction, and is a convenient excuse to justify involving human characters in a task that could otherwise be done by machines. Gene Roddenberry’s Andromeda used the conceit with its slipstream drive, which was very similar to spore drive. They were going by the mistaken interpretation of quantum mechanics that presumes a quantum superposition needs a conscious observer to resolve into a single state (e.g. Schroedinger’s cat being alive or dead), when actually sentient observation is just one example of the kind of interaction with an ensemble of particles (such as a brain) that correlates that ensemble with one specific state of the particle. For some reason, they presumed that only an organic being would count as a conscious observer, even though the universe had plenty of fully sentient artificial intelligences. It never really made sense except as an excuse for manual piloting.

But there are some Trek precedents for the idea. Like it or not, there’s always been a strain of mysticism included in the Trek universe, of psychic powers and the ability of the mind to transcend the physical. TNG’s “Where No One Has Gone Before” spoke of a unity between matter, energy, and thought, and featured a propulsion technology that used that unity to allow near-instantaneous intergalactic travel through the willpower of the Traveler. So perhaps we can presume that the pseudo-tardigrades have abilities similar to the Traveler.

@12/Jana: There are also Trek precedents for spacegoing life forms that can subsist on pure energy or that are partly energy-based themselves. Alternatively, maybe the mycelial plane is a subspace domain that’s something like fluidic space on Voyager, a continuum filled with an organic, life-sustaining fluid substrate.

@15/Christopher: I know about energy beings, but if they’re fungi, I would expect them to decompose organic matter, not live off energy. But fluidic space is a good precedent.

Yeah, I’ve posited before that we could retcon Traveller abilities to be mycelial-related.

@16/Jana: Trek has posited corporeal life forms that feed on energy before, like the space jellyfish creatures from “Encounter at Farpoint” (or star-jellies, as I called them in Titan: Orion’s Hounds).

Besides, P. stellaviatori is shown both to grow on planet surfaces (or in starship greenhouses) in normal space and to extend mycelial “roots” through subspace. So presumably they get their physical nourishment from the soil that their normal-space component grows in.

@18/Christopher: I’m fine with life forms that feed on energy, I just wouldn’t call them fungi.

“Magic. Got it.”

@19/Jana: Doesn’t every life form feed on energy, though? We extract chemical energy from the molecular compounds in the foods we eat.

Once again, we’ve seen that P. stellaviatori does exist in normal space and grow in soil and air and so forth. We saw Discovery regenerating its supply in episode 14 by terraforming a moon, depositing fungal spores and accelerating their growth. That part of them does act like a fungus, just one with some unusual properties like reproducing really fast and glowing and so forth. They just have an additional ability to extend their mycelium into a subspace domain, as well as through the soil.

Besides potential jokes about a student walking into a physics exam thinking they are about to take a biology final (while high), this moves Trek away from science-based to science-adjacent, science-as-metaphor for kooky stuff.

Which is fine. A show gets to define itself as it will. There are already pulpy and campy elements there, like an evil emperor on the loose. Perhaps they can double down on the time travel properties of the mushroom highway, bringing this show into Doctor Who territory. I’m a Who fan and know that we have to accept the silliness to enjoy the show (like the one where the moon was always a giant space egg). Once we know what kind of show we’re watching, we can just relax into it.

But if this season was criticized for not being Trek, just wait till they get a hold of next round. And it still leaves the giant problem where no one else knows of a mushroom network for the next few hundred years. Janeway is going to be pissed when she finds out.

@22/Sunspear: Like I said, there’s nothing new about Trek including fanciful or metaphysical elements. TOS had tons of aliens with psychic powers and species that had evolved into incorporeal forms with godlike abilities. TMP had V’Ger transcending physical reality by uniting with a human who could imagine a higher, more metaphysical plane (there was an intent that Will Decker was very interested in spirituality and transcendence and all that very ’70s New Age sort of thing, but it was left out of the final script). TWOK had the sheer fantasy of the Genesis Device. TNG gave us the Q, the Traveler, the Edo God, the Douwd, and other godlike superbeings, and dabbled in mysticism in episodes like “Where No One Has Gone Before” and “Haven.” DS9 had the Prophets, which started out as extratemporal aliens but were written more and more like genuine gods as the series went on. And so on.

I’ve always preferred to focus on the more scientifically grounded, plausible side of Trek myself, but I’d be dishonest with myself if I pretended the more fanciful side hadn’t been there all along. Trek has always been torn between the impulse to strive for credibility and the general tendency of SFTV to embrace fantasy and metaphysics.

Hey, but it’s cool to complain about the newest Trek and ignore the same things in the previous ones.

@23/Christopher: All true, but I’d say there’s still a difference between our heroes meeting aliens with implausible or mystical abilities (and then having a more scientifically grounded adventure next week) and using fantasy technology themselves. I guess you could argue that warp drive, transporters and universal translators are fantasy technology too, but without them, they couldn’t have visited alien planets and talked to the people at all.

@25/Jana: There’s actually a fair amount of real scientific theory behind warp drive; the very concept of a space warp, or of spacetime as something that can be warped, is derived from Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity. And Star Trek was a huge leap ahead of most other ’60s and ’70s SFTV in actually acknowledging that some kind of faster-than-light drive was needed for interstellar travel. The Jupiter 2 in Lost in Space and the Moon in Space: 1999 just drifted from planet to planet through normal space most of the time, although season 2 of 1999 did occasionally throw in a handwave about falling through naturally occurring space warps. In Battlestar Galactica, the ragtag fugitive fleet somehow managed to wander through several different galaxies in the course of one season even though “lightspeed” was their stated maximum velocity — and the one time we saw it crossing “between galaxies,” they were directly contiguous, like crossing a border between states in the US or countries in Europe. So as sci-fi FTL drives go, Star Trek was pretty much on the plausible side compared to its contemporaries and successors. (One of the few virtues of the 1979-81 Buck Rogers in the 25th Century is that it did acknowledge the need for a special FTL technology to achieve interstellar travel, a jump gate-type system called stargates. Though season 2 mostly abandoned this and just had its featured starship use something vaguely referred to as “plasma drive.”)

There’s also some scientific thinking, however loose, behind the idea of breaking matter down into constituent particles to teleport it, or the idea of scanning brain waves and interpreting their meaning into verbal equivalents. While the technical details of transporters and translators were imaginary and the obstacles glossed over, I wouldn’t call them fantasy. Science fiction doesn’t require that its concepts actually work in real life, just that they have enough of a grounding in scientific theory to seem more or less possible even if they fudge the practical details.

In a way, the spore drive idea is trying to be science-based. It’s grounded in at least one real-world scientist’s theories, though I couldn’t say how credible he’s considered to be by other scientists. It just takes those theories and applies them to something pretty much unrelated to them, which is why it’s so incongruous. It’s taking something that was probably proposed more metaphorically — that the type of interconnected system represented by fungal mycelial networks may be analogous with other networks of interconnections in other aspects of the universe — and interpreting it literally, by having fungi and tardigrades and so on actually physically exist in space. Which I think is clumsy as hell, but at least they’re not completely pulling the idea out of thin air.

@CLB: add Apollo from TOS to your list and the implication that the pantheons of Earth were all aliens; or “God” himself from STV.

As far as transporters, the energy required to convert matter, such as organic bodies, to an energy pattern and back would be so massive as to make it completely unfeasible. Think I read somewhere that it would take the power of a small star for each transport. It’d be like trying to contain the fission and fusion reactions of a thermonuclear bomb.

Also reminds me of a story by James Patrick Kelly, “Think Like a Dinosaur”: where “… a woman is teleported to an alien planet, but the original is not disintegrated because reception cannot be confirmed at the time. Reception is later confirmed, and the original, not surprisingly, declines to “balance the equation” by re-entering the scanning and disintegrating device. This creates an ethical quandary which is viewed quite differently by the cold-blooded aliens who provided the teleportation technology, and their warm-blooded human associates.” (from the wiki)

The transported human is actually a copy and the original is expected to destroy herself; no extra copies floating around allowed.

@27/Sunspear: “As far as transporters, the energy required to convert matter, such as organic bodies, to an energy pattern and back would be so massive as to make it completely unfeasible.”

Which is why TNG retconned it into a particle stream rather than matter/energy conversion.

Still, as I said, there is a big difference between a fantasy idea and an idea based on an impractical application of a real scientific principle. Yes, the amount of energy that would be released in full conversion of matter would be prohibitively large to allow practical teleportation, but the intrinsic idea that matter can be converted into energy comes directly from real physics. The understanding that matter and energy are equivalent and interchangeable is scientifically sound, even if that specific application of the principle is prohibitively impractical. So it’s not the equivalent of, say, casting a magic spell of translocation, or just finding yourself on another world because you wished really hard. Those are fantasy. Transporters are just soft science fiction.

“The transported human is actually a copy and the original is expected to destroy herself; no extra copies floating around allowed.”

Yeah, “Think Like a Dinosaur” is one of the more noteworthy explorations of that idea, though far from the first. Anyway, here’s my take on the question from my blog: https://christopherlbennett.wordpress.com/2011/12/01/on-quantum-teleportation-and-continuity-of-self/

@28. CLB: Interesting read, Chris. This part:

“…that your own self-awareness, your consciousness, would be preserved and unbroken through the process even if you were physically nonexistent for years between transmission and reception (say, if you were beamed across an interstellar distance, or if the hard drive containing your classical data got lost for a while…”

Made me think of Richard Morgan’s Altered Carbon, where human consciousness/self/identity is stored on “stacks” derived form alien tech. The physical bodies are just “sleeves” that carry the minds. A biological female (by birth) can inhabit a male body and vice versa. This stored self can also be beamed to storage, whether near or to other planets. Some people are more attached to their original bodies, creating clones that receive the ID stack (restricted to the super-rich, of course), thus ensuring a form of immortality.

(Still wish we’d gotten a review of the Netflix series around here.)

Edit: one of my favorite examples of this sleeve switching involves a crude thug brought into a police station. A detective then uses him to house her dead grandma’s stack for the Day of the Dead and brings him/her home for family dinner. Granma from bathroom to grandkids, “Hey kids, I’m peeing standing up!” Then, the same sleeve is inhabited by a bad guy we’d met earlier, complete with same accent. Brilliant work by the actor to convey all that.

To the author:

You suggested that people could eat the fruiting bodies of mycelium grown on spilled petroleum but the literature on the use of fungi in bioremediation suggests that heavy metals are concentrated in the fruiting bodies. A useful tool in healing landscapes but not one you’d want to eat the fruits of.

I DID study mycology and recently recorded a little guest bonus podcast about the science of the mycology in Star Trek Discovery, which you can find here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zqwe016dDpA

Thanks for sharing, Emily. I will definitely listen to it. Although, given the title “The Unbearable Wrongness of Mycelium Science”, I can intuit in which direction your opinion lies.

@31. Emily: Ouch! Even I’ve not gone as far as “…googling random real science words and using them to sound like Gwyneth Paltrow selling Goop” or “fake science sounding incoherent.”

We have some very earnest rationalizers on this site, who are prepared to embrace the “complete crap that makes the show sound idiotic.” As I’ve joked before, this is what you’d get from a college freshman who fails their Biology 101 exam, but thinks they’ve come up with some awesome ideas, because they got high.

This is unfortunately what Fuller, and his obsession with real life Paul Stamets, has hobbled the show with. Apparently, the current showrunners couldn’t have left well enough alone and shelved this nonsense.

@31/Emily: That was great. I loved your thorough analysis of selected quotes.

@33/Sunspear: I don’t know if you’re referring to me, but my attempts to rationalize what Discovery has added to Trek canon are hardly earnest — more like resigned. We’re stuck with this stuff now, just like we’re stuck with all the other absurdities of Trek pseudoscience over the decades like humanoid aliens and Galactic barriers and Earth duplicates and godlike cosmic beings, so it’s just a matter of trying to make the best of it and find some way to pretend it makes some kind of sense in Trek-universe terms if not in real-world terms. There’s a ton of stuff in Trek that I’d rather not embrace, but we have to take the bad with the good and try to make the best of it. I’ve gotten whole novels out of my attempts to impose some kind of plausible order on the scattershot ideas of Trek canon, including some I’ve particularly hated, like the gratuitous Earth duplicate in “Miri.”

For that matter, part of the reason I got into writing original science fiction is because it lets me create universes that don’t have the stuff I don’t like about Trek and other SF franchises. Working in Trek, I have to accept and rationalize these things, but working in my own universes lets me do things the way I want.

I share your skepticism about Stamets’s theories, but it’s worth remembering that in the ’60s, a lot of researchers took psychic phenomena seriously. There was a fair amount of research on the subject that was eventually exposed as junk science or the result of well-intentioned scientists being duped by fraudulent psychics, but before it was debunked, it looked to many people as if there might actually be something to it. And that’s why we got Vulcan mind-melds and Gary Mitchell and Miranda Jones and Deanna Troi and all the other psychic aliens and humans in Trek. Along similar lines, there was once an experiment that appeared to show that flatworms could absorb memories from other flatworms when fed their remains (ew), leading to all sorts of theories about “memory RNA.” The flatworm experiment was never replicated and proved to be a fluke (ahem), but even after it was discredited, science fiction writers continued to use the concept of memory RNA as a means of transferring knowledge or memories between minds, because it was a useful plot device. I believe both John M. Ford and Diane Duane used it in their acclaimed Star Trek novels in the ’80s, well after the science had been debunked.

It’s as much a matter of marketing as science. If they called it the, I don’t know, the transdimensional network and used fictional crystals like dilithium instead of spores, wouldn’t it be easier to accept? Crystals are rooted in mysticism and pseudoscience and still have an air of mystery surrounding them, and can still sound scientific enough to be plausible, while spores are… something else.

For me, it often reminds me of the line from Futurama. “Remember that episode where you got high on spores and smacked Kirk around?” Just a bit too much comedy in the word.

And like the episode of Married with Children where aliens use Al Bundy’s dirty socks for spaceship fuel (yes, this really was an episode), using a mundane thing like mushrooms for a super advanced starship is going to be an eyeroller. Not to mention all the baggage of tiresome old hippie jokes.

@36/Redd: Crystals are real physical things that have a lot of useful properties. Salt is a crystal. Ice is a crystal. Silicon is a crystal. Industrial diamond is a crystal. Metals and ceramics are polycrystals. Semiconductors are generally made of crystals doped with controlled impurities. Many types of display device are based on liquid crystals (LCDs). Crystals are hardly “rooted” in mysticism or pseudoscience. The fact that mystics have ascribed some crystals with magic properties does not give them any kind of exclusive claim to the very idea of crystals.

If semiconductor crystals can conduct current, there’s no reason a dilithium crystal couldn’t conduct ship’s power. The intent behind the creation of (di)lithium crystals was scientific in basis, not mystical. Stephen Kandel simply wanted a substance that was vital to a starship’s power circuits and that could be obtained directly from a mining colony, such as a crystalline mineral. His coinage of the term “lithium crystal” was, if anything, redundant; metallic lithium is already crystalline in structure, like most metals. That’s why they changed it to the imaginary “dilithium” later on. But there are other types of lithium crystal in real life, such as lithium fluoride crystals, which make good lenses for certain types of telescope (another way of channeling energy).

#37

Again, I’m not talking about science. I’m talking about marketing. I’m aware crystals are real things, and I’m very happy to share this existence with them. But crystals in fiction, particularly in fantasy, do hold a kind of mystical allure. Wizards and other mystics are often shown using crytals. The special ingredient in a lightsaber is a crystal. And if you can cross the streams and give your fictional crystal a scientific sounding name like dilithium, well then you’re really cookin’ with Crisco. You get the magic of fantasy and science all in one.

Less can be said about mushrooms. Unless you’re Super Mario.

@35. CLB: it goes beyond having to accept “idiotic” concepts for purposes of writing tie-ins. It requires people like you to appear to defend these ill-advised choices. Instead of quietly letting it go, they are doubling down for season 2. Which apparently entails real risk for CBS. Netflix is funding only a fraction of the production this time. There was little to no risk for season 1 because Netflix paid for most of it. CBS’ reported streaming numbers are using some creative accounting, citing cumulative subscribers, without citing cancellations. So, this could end badly from the business side.

But there may still be time to retool these concepts. Go with dark energy drive, or invent “sciency” tech and go with that. As Emily says, “For god’s sake, get a real science consultant if you’re going to attempt to use real science, much less current science that may get debunked.” (paraphrase) In this case, the show, more specifically Fuller, based their concepts on a TED talk by a self-taught mycologist. His theories are free-ranging precisely because they are not accredited or peer-reviewed (as far as I know).

@38/Redd: You’re overgeneralizing. Yes, in some contexts, crystals can be portrayed as mystical. But it makes no sense to assert that means every crystal in the history of fiction is mystical. I mean, there’s a lot of fantasy fiction where trees are mystical, but that doesn’t mean every story with a tree in it is using it in a supernatural way. There’s fiction about haunted houses, but that doesn’t mean every story with a house in it is a ghost story.

@39/Sunspear: “CLB: it goes beyond having to accept “idiotic” concepts for purposes of writing tie-ins. It requires people like you to appear to defend these ill-advised choices.”

I’m not “defending” anything. I’m just putting it in context. Star Trek has been doing comparably silly things for 50 years now, whether we like it or not. And we can either waste energy throwing temper tantrums over something we can’t change, or we can apply that energy to trying to turn a negative into a positive. I decided long ago that I’d rather do the latter.

#40

Yes, I am overgeneralizing. Such is the nature of marketing. And you’re being overly specific. Such is the nature of science.

Consider why Roddenberry named his fictional starship Enterprise. That name had a reputation for strength and toughness to the WW2 generation to which Roddenberry belonged. Because words and names have reputations. Some good, some bad, some ridiculous. People, that is the general audience, associate certain words and names with the things they know. It’s doubtful we’d be here 50 years later talking about this had the good, handsome starship been named the USS Lollipop or HMS Bounty. That ship just ain’t gonna fly, man.

Agreed, Star Trek has done some silly things, the space amoeba comes to mind, but must we add to them?

@41/Redd: Yeah, but you’re wrong if you think that most people who hear the word “crystal” will automatically go to mystical hoodoo as their default association. That’s a fringe belief, not a mainstream idea. I just typed “crystal” into Google, and the list of predictive-text continuations includes such things as “crystal definition chemistry,” “crystal drink,” “crystal palace,” “crystal champagne,” “crystal springs resort,” “crystal gayle,” and “crystal pepsi,” but it’s not until pretty low on the list that “crystal healing” shows up. Oh, and “crystal skull hoax” shows up on one variation on the list but nothing else about crystal skulls, suggesting that the majority of searchers for that particular bit of idiocy are on the skeptical side.

#43

Right, it’s about the shared associations of a word across culture. Type in the words “mushroom” and “spore” and see what you get. I’m going to go out on a limb and say crystals are a little sexier than mushrooms, that’s all.

But like you said, Star Trek already has had a lot of silly things in it. What’s one more?!

By the way, I did a search with the words “fiction crystal” and this was the first article to come up.

http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/PowerCrystal

@CLB: All right, lets not call it defending, let’s call it being passionate about “putting it in context.” And there have been a few who have become irate about this show, sometimes irrationally so.

In my case, I can’t get angry at a show, whether its production staff or performers. If things get too stupid (see the Walking Dead article/post), they lose my interest. I’m more amused by the terrible grasp of science in a science fiction show. ( I laughed my ass off at Emily’s Paltrow Goop analogy.) Yes, there’s always been patented Trek techno-babble. But at least draw from the proper discipline, in this case Physics.

Or, go the BSG route and just call it FTL and forget it about it. Making it a story element that then requires further integration seems misguided at this point. Perhaps the only thing that could save it is another time jump past all the established series.

Just to add, aside from the link in @31… I haven’t read his published papers, but from what I’ve seen in his TED talks and some more general level articles I checked, real world Stamets’ science is generally fine. He doesn’t have an actual university affiliation and runs his own online store promoting mushroom growing kits and herbal medicine and stuff, so there may be a little bias away from a pure scientific background, but yeah, fungi are amazing and can thrive in toxic environments and have many uses and many more we haven’t discovered yet. The problems occur where a team of completely unscientific Hollywood writers take Stamets’ theoretical speculations and then stretch them past the breaking point of imagination into total fantasy.

Where I think the original article goes seriously wrong in the theorizing is this paragraph:

“As Stamets states in Mycelium Running, “I believe mycelium operates at a level of complexity that exceeds the computational powers of our most advanced supercomputers” (Stamets 7). From there, Stamets posits that mycelium could allow inter-species communication and data relay about the movements of organisms all around the planet. In other words, mycelium is nature’s Internet. Thus, it is not too far of a leap for sci-fi writers to suggest that a ship, properly built, could hitch a ride on that network and direct itself to a destination at a rate comparable to that of an email’s time between sender and recipient, regardless of distance.”

Sentence 1: Here we start with something Stamets “believes”, not something proven to be fact.

Sentence 2: Based on this BELIEF, not fact, Stamets now “posits” (suggests or theorizes), again with no factual basis. I can posit that Elvis is still alive and the earth is flat, but without facts and evidence that doesn’t actually mean anything real.

Sentence 3: Now we are taking a leap based on an theory based upon a belief. We are now three degrees away from anything proven to actually resembling factual reality.

And in fact, even if the first two sentences were totally true, it IS too far a leap. We have (item A) one fungal root network through which tiny molecules travel at a moderate speed through hair-fine tubes; and (item B) one starship. Putting these together doesn’t connect. This sentence is the logical equivalent of saying “hey emails travel fast in a computer network, so it’s not too far a leap to imagine I could email myself to work instead of driving there”. There is a HUGE step missing in there, just as there is a HUGE step missing in explaining how a starship could connect to a mycelial network that does nothing but move molecules around at speeds rather slower than email.

Also worth noting that although email does move fast from the perspective of us sitting on one planet, it does not move faster than light. Electrons actually travel at only about 1% the speed of light, and take about 18 seconds to get around the earth. The nearest planet to us, Alpha Centauri, is 4 light years away, meaning it takes light 4 years to get there. So it would take an email traveling at only 1% that speed about 400 years just to reach Alpha Centauri. Molecules travel through mycelium rather a lot slower than even email, so clearly neither email nor mycelium is an efficient way to travel across the universe even if a starship could somehow use those networks. :)

@44/Redd: Crystals were already taken (dilithium).

@46/Sunspear: Physics and chemistry (dilithium).

@47/Emily: You just addressed one point I had been wondering about – Why would it be fast? So the answer is that it wouldn’t.

#48

I didn’t mean they should use dilithium again specifically, rather something along those lines. Something a little more mysterious than spores.

I’ll give Discovery points for originality with their propulsion though. Daft but original.

@49/Redd: Yes, I know. I meant that using a different kind of crystals might have looked repetitive.

When it comes to food-related space travel, I prefer Douglas Adams’ Bistromathic Drive.