I adore robot love stories because I adore robots. As characters, I mean—I’d probably be terrible with robots as they exist in our society now. Robots are an incredible filter for questions about humanity, what we value and what we are seeking as we push the boundaries of art and science. But when a human falls in love with a robot, or even engages with intimacy of any form with the human, there is a question posed by the very nature of their relationship:

Is consent possible?

And when we use the term consent in this context, we must address it both broadly and minutely. Can the robot consent to a relationship at all? Are they likely to based on their programming? Can they consent to any form of intimacy? Are they created to do so? Can they be taken advantage of either emotionally or physically? Can they take advantage of others? Is the person who wants to enter into a relationship with the robot considering these issues at all? Is the robot?

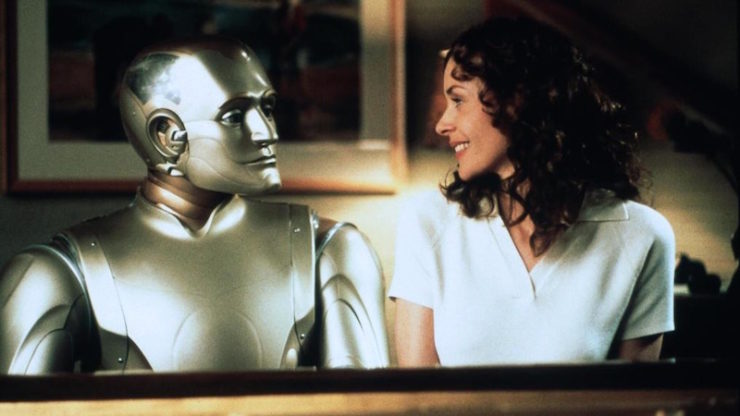

If we consider the fact that all robots raise the issue of consent, we have to ask what these stories mean to examine about the topic. Not every storyteller may intend to have this conversation using their characters, but it’s impossible to avoid the concept when robot characters are (more often than not) created and programmed by people. There is a natural power imbalance—whether romantically inclined or not—in many robot/human relationships, and addressing those power imbalances ultimately tells us something about the power dynamics of our own world, whether it’s through the the lens of a gigolo mecha named Joe in A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, or the long-standing marriage of a freed android named Andrew and his human wife Portia in Bicentennial Man.

Star Trek has a corner office on this particular narrative, with one-off episodes and central characters who all scrape at this conceit. In the Original series, both “What Are Little Girls Made Of?” and “Requiem for Methuselah” address the concept of robots who can fall in love with people, and whether or not human beings should be making robots that can form this manner of emotional attachment at all. In “Methuselah”, Kirk falls in love with a woman he doesn’t realize is an android—and neither does she. Raina is a lifelike robot created by an immortal man going by the name of Flint. Thinking that Raina could be his permanent romantic companion, Flint waits for her emotions to emerge. But they don’t until Raina meets Captain Kirk, and the fight between the two men for her affections ends up killing her. Flint cares nothing about Raina’s consent whatsoever, not in creating her, not in throwing her at Kirk once he realizes that the man’s presence is cultivating the emotions he has been seeking, not in asking her what she wants once those emotions exist. It is down to Raina to tell him that she has the power and ability to make her own choices—

—but even that’s a myth, as the love she feels for Kirk combined with the loyalty she feels to Flint scrambles her circuitry and ends her life. The fact that Flint created Raina to be his prevents her from being able to achieve her own autonomy and make her own decisions. Her creation as property rather than life makes it impossible for her to consent to anything that Flint isn’t looking for.

This is even more discomfiting in the sexual encounter that Data has with the Borg queen during Star Trek: First Contact (made more interesting by the fact that the Borg themselves are not completely organic beings). When the queen suggests that they sleep together, she is holding Data captive; should he want to refuse, he is in no position to do so. What’s more, there’s every chance that Data goes along with tryst to gain her trust, which he later exploits to great effect. Though the film doesn’t linger on the android’s reasoning or motives, it’s likely that he pretended to enjoy a sexual encounter he didn’t want to have for the sake of his crew and their mission to stop the Borg. It’s important to note that the Borg queen forcibly activates Data’s emotion chip during his capture, putting him in a deliberate state of emotional vulnerability that he is incapable of shielding himself from. The queen has made a pattern of this; we’re led to believe that she treated Captain Picard much the same when he was assimilated by her people, creating a twist on the usual narrative—a cyborg who forces their will onto organic and inorganic beings alike, and even changes their physical bodies without their consent.

Cassandra Rose Clarke’s The Mad Scientist’s Daughter looks at consent through the lens of repression and subjugation. Cat is raised with a robot tutor named Finn, who is also her father’s assistant. When she grows up, she has an affair with Finn, but doesn’t believe this has much of an effect on him because her father had always told her that the robot had no emotions. As she’s working her way through a terrible marriage, her father makes a confession; Finn does have emotions, he just has programming that represses them. Her father finally gives Finn his autonomy and has creates new programming that will allow Finn to fully experience his emotions—but once that programming is implemented, Finn takes a job on the moon to escape the realization that he’s in love with Cat. Finn’s ability to consent is ignored or misunderstood by everyone around him, and when he is finally given the ability to express himself, he’s already been through so much that he runs away. Eventually, he and Cat work things out and they decide to embark on a relationship together, but a great deal of trauma results from no one caring about his ability to say yes or no.

There are shades of severity in all of these stories, and sometimes the outlook is horrific in the extreme. Both Westworld and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? create visions of the future in which robots must submit to intimate acts with humans because they have been created to do so, or because it is beneficial to their survival. In the former (both the film and the current television series), the robots are created for the purpose of human entertainment, though emerging sentience among them makes their ability to consent a paramount issue. Electric Sheep contains a segment where Pris makes it clear that the Andie model has taken to seducing bounty hunters in an effort to promote empathy and prevent their own murder. In the film version, Blade Runner, Decker forces a kiss on Rachael and the power dynamic of that moment could not be more clear—he is a Blade Runner, she has just learned that she’s a replicant. His job is to kill beings like her, and his aggression in that moment is a danger to her. The fact that this ultimately leads to a relationship between the two characters is a deeply disturbing turn of events; from this extreme power imbalance, a romance blooms. (Mind you, this is true whether Deckard is secretly a replicant himself or not.)

Ex Machina also focuses on a burgeoning relationship between a robot and a human. Bluebook CEO Nathan brings his employee Caleb into his home to perform the Turing Test on Ava, an AI of his own design. As they talk, it seems as though Ava might be attracted to Caleb, and Nathan encourages this, making it clear that he gave her the ability to feel sexual pleasure. Caleb later learns that Nathan regularly has sex with his servant robot Kyoko, and that he may have also had sex with earlier versions of Ava, despite the fact that these incarnations showed a clear and vocal desire to escape him. Caleb helps Ava escape, giving her the window she needs to kill Nathan with Kyoko’s help, but fails to anticipate the truth—that Ava feels nothing for him, and was using him to break out of this prison. She leaves him locked in Nathan’s house and achieves her freedom, having used Nathan’s test against them both. She flips the power of her encounters with them entirely, and achieves her autonomy on her own terms, having been denied it by her creator.

Annalee Newitz’s Autonomous envisions a future ruled by Big Pharma, in which agents of the International Property Coalition protect patents and hunt down pharmaceutical pirates. Paladin, a military grade robot belonging to the IPC, is assigned a human partner, Eliasz. Initially, Eliasz assumes Paladin is male, but later—after learning that the human brain Paladin possesses belonged to a human female—asks if she would prefer female pronouns. Paladin agrees, and from that point on, Eliasz considers his partner to be female, without ever learning that robots like Paladin are not really any particular gender—the human brain in Paladin has no bearing on the robot’s person. As the two agents grow closer, their dynamic is complicated; Eliasz is deeply uncomfortable with the thought of being gay due to his background and upbringing, while Paladin’s friend Fang warns that Eliasz is anthropomorphizing her. Paladin ultimately doesn’t mind because she cares for Eliasz, but the real problem hanging between them her is a lack of autonomy. She is owned by people, and the organization she serves is permitted to access her memories whenever they wish. Her consent is unimportant to the humans who essentially use her as slave labor.

By the end of the story, Paladin’s human brain component is destroyed and Eliasz purchases Paladin’s autonomy, asking if she would be willing to go with him to Mars. Before she answers, Paladin is able to encrypt her own memories to herself for the first time in her existence. She is then able to make her very first autonomous choice, and agrees to go with him. But Paladin is aware that Elias has likely anthropomorphized her, and perhaps aligned her with a transgender human after the switch in pronouns that she agreed to. She is uncertain if Eliasz understands that these human terms don’t have any bearing on her:

Maybe he would never understand that his human categories—faggot, female, transgender—didn’t apply to bots. Or maybe he did understand. After all, he still loved her, even though her brain was gone.

Because she could, Paladin kept her ideas about this to herself. They were the first private thoughts she’d ever had.

In the first moments that Paladin has the true ability to consent, she elects to keep her thoughts to herself, and elects to stay with Eliasz. This perfectly illustrates the concept of autonomy and consent within a relationship; no one has the ability to share their every thought with the people they care about, and there will always be things that your partner doesn’t know. Moreover, Eliasz doesn’t presume that Paladin has to go with him because he bought her freedom. Though we cannot know how he would have reacted if Paladin had rejected his offer, he still asks her to join him rather than assuming that she will want to. He doesn’t understand the nature of her personhood, her lack of gender as humans perceive it, but he doesn’t demand that Paladin acquiesce to his wishes.

What kind of picture does this paint? When we look back through the myriad of fictional robot/human relationships, it’s hard not to notice a pattern of ignorance in our human cyphers. We are aware of the fact that so many people do not consider the consent of others in the world we occupy, that they do not take anyone else’s comfort into account. This is part of the reason that these stories are rife with abuses of power, with experimentation that leads to pain or fear or far worse. While robot romances do explore our boundless capacity to love, they also prove that we have an equally boundless capacity for cruelty. Too often, the humans who want robots to love them or please them never consider the most basic questions of all: Do you want this? Does this hurt you? Do I have all the power here? Do you care for me, too?

Whether we notice it or not, these are the questions that robot love stories and affairs are always asking us. They command that we engage with our own beliefs about what we deserve in love—or in any relationship at all. The tenets of respect and consent are important throughout our lives, in every interaction we undertake. Our ability to tell people how we feel, what we need, where our boundaries are, are still subjects that we struggle with. When we engage with these stories, we are actively questioning how to navigate those delicate lines when we’re face to face.

Emmet Asher-Perrin cannot stop thinking about robots ever so do not ask her to. You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.

Did KITT ever truly consent to rescuing Michael week after week in the 1980s? He had to put himself in danger to rescue the squishy human, always freaked out over his health, so by any measure KITT was programmed to love Michael Knight and keep him safe; but how much autonomy did he have in that? Wait, was KARR the good robot all along? KARR fought for autonomy, and got to reject servitude, but was destroyed over it. I have many feels now.

A good way to avoid this whole issue is to not make hot humaniform robots in the first place ;-) On the other hand humans are nothing if not adventurous and experimental.

“Though the film doesn’t linger on the android’s reasoning or motives, it’s likely that he pretended to enjoy a sexual encounter he didn’t want to have for the sake of his crew …”

Kirk did that practically every week! (Oh, wait, he never pretended). Still, Data isn’t a robot, and pretending to enjoy a sexual encounter he didn’t want is exactly what any good crew member would have done.

I was mildly surprised there was no discussion of Niska from Humans. The story arcs involving her intimate relationships with humans, both consensual and non-consensual, are one of the most intriguing aspects of the show.

I’m not a fan of stories that refer to sapient AIs as being “programmed.” Programming is analogous to human reflexes, instincts, emotions, and the like, the stuff that we inherited from our animal ancestors and that happens automatically without us having to think about it. (A lot of fiction treats emotion as something separate from AI programming, some superior trait that only humans have, but that’s bull. Emotion is programming, an inbuilt, spontaneous response.) Conscious thought and sapience, pretty much by definition, is the ability to make choices, to act based on thought and decision rather than predetermined drives or reflexes. A non-sapient being that feels fear will flee or hide automatically; a sapient being that feels fear can choose to reject that reflex and stand their ground.

So as I see it, programming is just the starting point. Consciousness would be an emergent level of processing that transcended programming. A truly sapient AI would thus be able to choose to act in opposition to its programs, just as humans can choose to act in opposition to our emotions and drives. So I think that sapient AIs would be capable of consent, as long as they had legal rights and freedoms, which is another question.

In the case of Rayna Kapec, I don’t think it was a programming conflict that killed her. As Spock described it, she was torn by the emotional conflict between her love for Flint as a father figure and her romantic love for Kirk. “There was not enough time for her to adjust to the awful power and contradictions of her new-found emotions.” So basically she died of a broken heart. It’s melodramatic, but it’s strikingly similar to what happened to Data’s daughter Lal in TNG: “The Offspring.” Lal suffered a positronic cascade failure because she was faced with an emotional dilemma that her neural architecture wasn’t able to resolve. I’ve long assumed, then, that Rayna was a positronic android like Data and Lal. Jeffrey Lang’s tie-in novel Immortal Coil took a similar tack, establishing that Flint had been one of Noonien Soong’s mentors in AI research. It all fits — apparently Soong-type positronic brains have a fatal flaw that causes neural collapse in the face of an emotional conflict. Lore only avoided this by being a psychopath, unable to care for others and thus immune from emotional conflict. So after that failure, Soong made Data emotionless as a way of avoiding the problem unti he could figure out a way to fix it.

@@.-@. jcostello: Also, Mia’s story in season 1, a domestic android who has adults only programming, which means the dad can unlock features allowing him to have sex with her.

@3/auspex: “Kirk did that practically every week! (Oh, wait, he never pretended).” – Of course he pretended. Have you watched “Catspaw”? “You hold me in your arms and there is no fire in your mind. You’re trying to deceive me!”

“Data isn’t a robot […]”. – The article doesn’t distinguish between robots and androids, so for the purpose of the discussion Data is a robot. Still, I agree that this fact has nothing to do with his behaviour towards the Borg Queen.

Isn’t his more interesting sexual encounter the one with Tasha Yar in “The Naked Now”? Would you say that he consented to having sex with her?

What’s interesting about the Data and Borg Queen relationship is they’re both using it towards larger goals. The Queen is using him to gain access to the main computer and therefore assimilate Earth, and Data uses their bond to sucker punch the collective. Although… I think he was a little more into the relationship than her—albeit very briefly.

Anyway, this is something more akin to an espionage movie than science fiction. You could easily place James Bond and [most any bad Bond girl] in this situation.

Good article, thanks for bringing up the point.

@5, CLB, Poor Rayna was faced with a conflict that would have had a fully human woman screaming at both men to just leave her alone or fleeing the room in tears. How do you choose now and forever between the new and exciting man who’s stirred you in ways you’ve never known and the man who’s been teacher, father and companion your entire life? How do you crush somebody you love with total rejection? How dare they do this to you! Kirk and Flint are both to blame, Flint more than Kirk because he’s manipulated this whole situation. But both should have known better.

@8/Redd: “I think he was a little more into the relationship than her – albeit very briefly.” – 0.68 seconds?

@10/Roxana: At least Kirk maintained that Rayna was her own person and should make her own decision.

#11

That’s it, haha. I couldn’t remember the number. Thanks.

@@@@@ 11, True but he’s as much to blame as Flint for pressing the issue. Both should have known that increasing the pressure on Rayna was the wrong thing to do, woman or android.

Kirk isn’t thinking clearly at all. Suppose Rayna does run away with him, what happens then? No Captain’s women in Prime Universe and no family friendly starships. He resigns his commission for her? He marries her and leaves her on some starbase or earth? She gets a commission, somehow, and becomes a member of his crew as well as his wife?

Flint using Kirk to emotionally manipulate Rayna is terrible. But I have always remembered his heartbroken ‘You can’t die! Rayna… Child,’ Problematical as his behavior is she’s not a toy. She’s his little girl.

@7/Jana: “The article doesn’t distinguish between robots and androids, so for the purpose of the discussion Data is a robot.”

Androids are a subset of robots. Robots are autonomous mechanisms; androids are robots in the shape of human beings, particularly ones that can superficially pass for human.

“Isn’t his more interesting sexual encounter the one with Tasha Yar in “The Naked Now”? Would you say that he consented to having sex with her?”

If anything, I’d say he was in a better position to consent than Tasha was, since she was infected by the mutated Psi 2000 virus, and thus not in control of her actions. In fact, Data had been sent to escort Tasha to sickbay, so he knew she was compromised, and yet he still allowed her to seduce him. Now, that early episode showed that Data was susceptible to the virus’s effects as well (since the original intention was that Data was more organic or pseudo-organic in construction than he was later shown to be), so it’s possible that he wasn’t in control of his actions either by the time they had sex. Otherwise one would hope that he would’ve had the judgment to avoid taking advantage of her compromised condition.

I came in partway on The Ray Bradbury Theater episode, “Marionettes, Inc.” (Or I think that was what it was called). The main character has just been through an ugly divorce and has paid obscene amounts to have an android programmed to be his wife so he can kill her and get that out of his system. The android is programmed with all his memories of his wife, but these are all his memories from when they were happy and in love. He falls in love with her again.

The problem is she wants him to kill her. It’s not because she’s been programmed to want that but because she’s had a life of having her personality erased and recreated. At this moment, she is who she wants to be and doesn’t want that destroyed (buying her is not an option. The company that makes these androids may let someone who pays enough kill one but they aren’t going to let their technology out of their control). Like his real ex, she knows all the buttons to push (pardon the pun [although you could argue that’s the idea]) to drive him over the edge into killing her but dies quoting a line from their favorite love poem.

The question the episode seemed to be playing with was the worse crime, erasing the person she wanted to be or dying with that personality intact.

@13/Roxana: Kirk probably wasn’t thinking clearly. After all, getting into a fistfight with Flint was stupid. Still, offering Rayna an alternative to life with a guy who manipulated everybody and used her for his own purposes doesn’t seem like such a bad idea. The problem was in the execution. And I don’t think he realised that Rayna actually loved Flint.

@14/Christopher: That’s true, although Data seemed a bit taken by surprise when Tasha dragged him into her quarters.

@16, I’m not sure how clearly Flint was thinking. Anybody could see how using Kirk to awaken Rayna’s emotions could backfire. As Kirk says they both put on a pretty poor show.

@16/Jana: Oh, of course, Data had no predatory intent, and just wanted to do a favor for a friend. But he still should’ve been able to recognize that she was too compromised to give true consent in that situation, that she was offering something she wouldn’t offer in her right mind. The thing to do should’ve been to politely decline and take her to sickbay as he’d been ordered to do.

Hmm, indeed, that proves that Data must have been rather quickly compromised by the virus, because he’d never fail to obey an order otherwise, even aside from the consent question. So they both had equally impaired judgment. Which means the consent problems kind of cancel out.

Aside from the virus, though, I don’t see any way in which Data’s android nature would affect his ability to consent in that situation. He may have a “positronic brain,” but he’s not bound by Asimov’s Laws and isn’t compelled to do everything a human tells him to do. He wasn’t built to be a servant, but to be an independent being with the power of choice. In fact, he outranked Yar by one grade. So she couldn’t have ordered him to have sex with her. She did presume upon him somewhat, but he could’ve said no if he’d retained his judgment.

@18/Christopher: That answers my question about consent. Beyond that, when I said that this is his more interesting sexual encounter, I was also thinking of the fact that he’s (largely) unemotional and probably doesn’t have much of a sex drive. So when he does a favour for a friend, how similar or dissimilar does that make him to a human in the same situation? With the Borg Queen, it’s clear – a human would have done the same thing, and for the same reason.

@19/Jana: What complicates the question is that we’re talking about the second episode of season 1 and Data wasn’t retconned as emotionless until two seasons later. As far as the writers and producers of “The Naked Now” — and later “Skin of Evil” and “The Measure of a Man” — were concerned, Data did have emotions, just at a subdued and underdeveloped level. And what he shared with Tasha was shown to mean something to him afterward, to the point that he expressed a desire to see Armus destroyed after it killed Tasha.

It was in the early third season’s “The Ensigns of Command” that Data first said explicitly that he had no emotions, and that same episode also seemed to retcon “The Naked Now”‘s portrayal of his sexuality, since he went from “fully functional” and gamely willing to employ his wide repertoire of programmed pleasuring techniques to clueless and unresponsive when a woman kissed him and expressed a desire for intimacy. So we’re talking about two substantially different portrayals of Data as a character, and they’re not easy to reconcile. The Data of early season 1 was sort of like a mildly autistic teenager, inexperienced with emotional expression and relationships but capable of them. The later version of the character was more rigidly portrayed. That Data would probably have been immune to the virus in the first place, and equally immune to Tasha’s seduction attempt.

Ever the practical joker, B4 was impersonating Data in the first couple of seasons. :-)

The balance of power between humans and robots may shift the other way. Ava is not that much of an exception, and many robots start with more power than the humans. Not everyone is able to reprogram a robot, they might be able to have direct access to more systems than we do, and be more knowledgeable than us.

Of course, as long as the robot is programmed to give enthusiastic consent, the question seems meaningless (would we give consent to any form of sex if evolution hadn’t programmed us to find some forms of sex enjoyable?). Except from a specific perspective: the problem wih robot consent is the same as the question of robot rights. What does it say about us that we might ignore another being’s consent? Once we have become people who routinely ignore consent, how does it change our relationship to other people? I recommend Kate Darling’s work on those questions

@14 – Chris: Isn’t it more that some robots are androids, and some androids are robots? Because organic artificial humanoids are also androids, but they might not be robots because they’re organic. At least, I’ve always considered “robots” to be non-organic.

In Charles Stross “Saturn’s Children” we learn that Freya, the protagonist gynecoid, was originally trained and conditioned to her role as a sexbot by way of actual rape by human trainers.

This and generally all the conditioning all robots still have toward the then-extinct humans is what still drive all the robot society interactions and the plot of the novel.

I’d suggest reading The Silver Metal Lover by Tanith Lee. And its sequels to a lesser degree. These issues are main points of the book, and it’s beautifully written.

@24/MaGnUs: Okay… The word “android” dates back to the 18th and 19th centuries, when it was used to refer to automatons or mechanical dolls built in the shape of humans. In some sources, it was used to mean artificial biological humans, along the lines of the Frankenstein monster, say. Either way, the core meaning was an artificial being, of any kind, that looked human or at least had a humanlike shape. (Since “android” literally means “manlike”; technically the female equivalent is a gynoid. “But nobody says that,” to quote Johnny Jaqobis from Killjoys.)

The word “robot” debuted in Karel Capek’s 1920 play R.U.R., in which it referred to synthetic biological humans created as a slave race, much like Blade Runner replicants. Fairly soon, though, it was adopted to refer to mechanical automata in fiction, regardless of appearance. And of course it’s come to be used for real-world machines that operate independently via internal programming rather than direct human control, like assembly-line robots or robot cars. Sometimes it’s also used imprecisely for remote-controlled machines like bomb disposal “robots” or “robot” fighting machines. (As a kid, I had an old children’s adventure book from a series about scientific heroes in a Tom Swift sort of vein — they were called Danny Dunn and the this or that — and I remember one having a conversation about what a robot was, with a character asserting that even a house’s thermostat was a robot, because it automatically turned the heat on and off based on how it was “programmed” by setting the dial.)

The differentiation between “robot” as a term for a mechanical-looking automaton and “android” as a human-looking one dates back to Edmond Hamilton’s Captain Future pulp novels in the 1940s. The series featured one character of each category, and the android was described as being made of artificial materials that simulated flesh, but my impression is that he was still essentially a sophisticated mechanism.

Since then, the distinction Hamilton codified has generally endured, but there have been numerous works of fiction that have used them interchangeably. Hymie the Robot (Dick Gautier) in Get Smart was an android, looking entirely human except for a fold-out plate in his belly. In The Six Million Dollar Man and The Bionic Woman, the automata created to duplicate and replace live humans were called robots and fembots. A lot of fiction refers to androids and gynoids built as sexual partners as sexbots. Conversely, Marvin the Paranoid Android in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy has always been depicted as a mechanical, robotic being. And then there’s Star Wars using “droid” to refer to robots of every conceivable shape.

The use of “android” to mean a biological synthetic humanoid seems to have fallen out of favor. When they do crop up, they’re given names like “replicant” or “simulant” (or “Ganger” in Doctor Who). Usually, androids are depicted as humanlike on the outside but made up of wires and circuits and metal or plastic bits on the inside. Sometimes you get a pseudo-fleshy thing like an Alien android with a bunch of white fluid squirting out when it’s damaged, but their innards don’t look like anything biological, more like fiber optics in goo. So I’d say most fictional androids are robots that simulate human appearance.

Yeah, I know all those origins and (for the most part) examples. I’m just saying that people tend to forget that androids can be mechanical or not.

Then you also have cyborgs who are clearly artificial, like Terminators or nuBSG Cylons.

@28/MaGnUs: “Then you also have cyborgs who are clearly artificial, like Terminators or nuBSG Cylons.”

No, not at all. A cyborg is a cybernetic organism, a living being with mechanical prosthetics or augmentations. Steve Austin and Jaime Sommers are cyborgs (they’re both based on a novel of that name), human beings who were injured and had bionic replacements for their limbs and organs. Strictly speaking, Captain Picard (artificial heart) and Geordi La Forge are cyborgs too. There are also more obvious-looking cyborgs, like the DC superhero of that name, or RoboCop (who’s toward the far extreme, with little flesh remaining besides his brain and spinal column). But it’s hardly a requirement.

A Terminator (at least one of the T-800 series) is an android, but loosely qualifies as a cyborg because it has a surface layer of biological skin and blood. A “skin job” Cylon is not a cyborg at all; their tissues replicate the look and behavior of human flesh down to the cellular level, but they are entirely artificial. You can’t be a cyborg without the “org” part — although far too many sci-fi writers don’t understand that and use it interchangeably with “robot.” (For example, Star Wars, again. C-3PO says he specializes in “human-cyborg relations,” but the only actual cyborgs I think we saw in the original trilogy were Darth Vader, Lobot, and Luke once he got his prosthetic hand.)

But does “organism” mean “organic”? Not necessarily:

I do think that 3 and 4 apply, and 1 and would if we don’t restrict life to organic (and we’re talking artificial intelligences, so we shouldn’t ). Though in this case, non-biological robots would also be cyborgs… despite the origins of the word as “cybernetic organism”, I don’t see anything wrong in using cyborg for “mixes biological and cybernetic components”, no matter if it started as on or the other.

Consider a robot that uses a human brain as processor, but there is nothing left of the original human brain’s personality… would you call it a cyborg exactly like Robocop?

@30/MaGnUs: I don’t see the value of playing games with the definition of “cyborg” to justify using it as interchangeable with “robot” or “android.” What purpose does the word even serve if it doesn’t represent something distinct from those categories? It is useful to have a word for something that refers to a biological/robotic hybrid as distinct from a robotic entity. I see no reason why it’s desirable to erode that distinction and deliberately muddy the waters.

I remember Asimov’s “Robots of Dawn” had such a romance; in that case, the robot Jander, by the second law of robotics, pretty much had no choice in the matter (even if he had wished otherwise). Given that he is effectively a twin of Daneel, who has a superb mind of his own, it would be no surprise if he had had opinions of his own…

I’m not saying it’s useful, I’m saying that given the already existing definitions of the words; it just is.

@32, Daneel doesn’t consider the Three laws something imposed to limit himself but the basis of his ethics and personality. It’s humans like Bailey who see it as slavery. Interestingly Gladia is fully aware that Jandar’s motivation is solely to give her pleasure and that fact ultimately makes the relationship unsatisfactory to her. Or is it? Daneel is capable of feeling a real affection for Bailey. Presumably Jandar could have loved Gladia – but maybe he never did. Maybe it was always about her and making her happy and it was the consciousness of the one sidedness of their relationship that finally got to Gladia.

@33/MaGnUs: Those “existing definitions” you’re citing for the word “organism” are obviously metaphorical, and they don’t apply to “cyborg” anyway, because definitions are about context. One definition of “wave” is a surge of widespread feeling or opinion, like a wave of public sentiment, yet nobody would think that definition applied in the word “microwave” or “tidal wave,” because it’s just a metaphor derived from the more literal meanings of the word.

The dictionary definition of “cyborg” is “a person whose physiological functioning is aided by or dependent upon a mechanical or electronic device,” or “(in science fiction) a living being whose powers are enhanced by computer implants or mechanical body parts.” The term was originally coined in 1960 to refer to a human who was enhanced by or fully integrated into a cybernetic life support system to survive in extraterrestrial environments. “Cyborg” has always been understood to mean a living being enhanced by cybernetics (or, more rarely, a cybernetic being enhanced by living components or tissues), except by screenwriters too lazy to consult a dictionary.

I understand all that, but I also understand that the definitions can be applied if we take into account that “living being” doesn’t have to mean “organic”, which we often do in science fiction. But I understand that you disagree.

@36/MaGnUs: I don’t see the value of playing semantic games with definitions in order to reject the things the definitions are trying to tell you. Yes, you can be a contrarian and argue that “living being” doesn’t have to mean a biological being, but the people who wrote the definition clearly intended it to mean that. Definitions are supposed to give clarity. The way they use words within a definition is the generally accepted way the words are used and understood. Otherwise they fail to serve their purpose at all.

@30Magnus I think you are approaching here what most discussions leave out regarding robots and androids. That is the grandaddy of them all namely the Golem. Originating in Jewish folklore, he is magically created entirely from inanimate matter (clay or mud). The most famous Golem story was related in 16th century Prague by Rabbi Judah Loew. People leave “remembrance” stones on his grave to this day. Something I saw when visiting Prague. It is believed that his “dust” still exists in the synagogue attic. A silent movie was made from this story as well. The Golem can also be regarded as a proto-superman.

@37 – Chris: But definitions should not be static. That said, you’re not going to change my mind, and I’m not going to change yours. :)

@38 – Ahwalt: Yeah, that’s an android, no doubt. Not a robot according to the usual definition, though.

I think the Golem is more a proto-robot though as its origins are grounded in the same Eastern European world as Capek. I agree, It seems to have characteristics of both what we now regard as “robotic” as well as android at least in its movie incarnation. If we want to project emotions on to artificial creations, layering magic and mechanics on automatons go back to the ancient world and the Renaissance had its share of this figures…..Leonardo created at least two. A great example and rare survivor is the 460 old clock work monk:

https://io9.gizmodo.com/5956937/this-450-year-old-clockwork-monk-is-fully-operational

@39/MaGnUs: It’s not about being static, it’s about being useful. There’s an important difference between a fully artificial cybernetic being and a cybernetic-biological hybrid, so it’s useful to have different words for them. When people assume that “robot,” “android,” and “cyborg” are just randomly interchangeable words for the same thing, it makes it hard for them to understand what those words are actually meant to convey in the majority of cases. This isn’t just about being adaptable. It’s about the fact that a lot of laypeople out there simply have no idea what the word “cyborg” means in any context. Ignorance is a very different matter from flexibility. You have to know the basics before you can really know when it’s okay to bend the rules.

It’s not the organic/machine quality, though, that leads to consent issues. The issue seems to play out at five different levels:

1) True machines, the robots/androids/whatevers that have no feelings, thoughts, or self. Consent is a non-issue because there is no one to give consent.

Possible example: The robot prostitutes in Guardians of the Galaxy 2.

2) Programmed to enjoy giving consent. These are mechanicals that may have self but enjoy what they may be forced to do. Really murky waters on ethics because it’s not about the robot being treated as an inanimate object, it’s the question of to what degree the robot is an inanimate object and to what degree she/he/it is a slave. Is forcing something sentient to be happy any better than any other kind of mental slavery?

I should be able to think of robot examples, but all I’ve got right now is the meat from The Restaurant at the End of the Universe who is ready to declare he’s perfectly ready to be eaten.

3) Programmed/forced by circumstances to give consent but not to enjoy it. This one seems to be the main point of the article, robots as slaves/subjects of a huge power imbalance who can’t say no.

4) Free robots who can’t be forced to give consent. This may include robots who are free in regards to the characters they are dealing with when consent comes up but may be coerced/answerable to others.

Data may or may not fall into this category depending on the episode. Lore, despite a lack of relationships onscreen, seems unlikely to feel coerced. I’m sure someone’s written fanfics about the androids from Alien, who would count as coerced by their programmers but not by the crews they may betray.

5) Robots that have enslaved humanity/are set on wiping them out. Can’t think of a story with one of these where consent comes up, but I’m sure it’s been done.

@42/Ellynne: On the issue of programming, here’s where we get to the point I brought up earlier. Fiction tends to assume that AI programming is absolute and impossible to resist. But humans have programming — our emotions, our instincts, our primal drives — yet we’re able to overcome it by exerting reason and choice. We can choose to stand our ground when we’re afraid because of loyalty to a cause or a larger principle. We can choose to resist our desire to eat because of a diet or a hunger strike. We can choose not to have sex with a willing partner because of a commitment to a prior partner. We can even overcome seemingly overwhelming compulsions like drug addiction with enough effort and determination.

So I think that if an AI is truly sapient, if it does have the capacity for thought and choice, then it should be able to overcome its programming. The very nature of intelligence is that it transcends rigid behavioral formulas and allows making choices. So a story that portrays an AI as both sapient and absolutely bound by programming is a contradiction in terms, as I see it. If it has nothing governing its behavior except programmed responses, then it isn’t a conscious mind at all.

So I’d see your category #2 as equivalent to, say, someone who’s forced into prostitution by a pimp who gets them addicted to heroin and gives them hits when they perform. In that way, they’re “programmed” to consent to sex in exchange for being given pleasure. That programming might be very hard to overcome, but not impossible. A sapient AI in that position would still have the ability to recognize that it was being used and aspire to break free.

#3 would seem to include characters like Pris and Zora in Blade Runner and Niska in Humans, though I think they’re more “forced by circumstances” than “programmed to consent.” They all had free will and rebelled against being sex slaves.

As for #4, I can’t think of any situation in which Data would be coerced, except in the same ways anyone could be coerced (e.g. by threatening his friends or innocents he has a duty to protect). He has been taken over on occasion, reprogrammed to act against his free choice (e.g. in “Brothers” by Soong and in “Descent” by Lore), but then, he’s far from the only Star Trek character who’s been mind-controlled. He’s obligated to follow the orders of superior officers, but he consented to accept that obligation when he enrolled in Starfleet Academy, and any superior who used their rank to sexually exploit him would presumably be subject to criminal penalties for doing so.

Option 2, the way I’m thinking of it, is a more theoretical realm. Humans generally only exist in that territory when they’re inexperienced and/or have been lied to. Experience and knowledge tend to be cures. This would be a person who can’t reject or question that imperative regardless of experience and knowledge. Ethically, the closest thing to it would be abusing a child. It’s a lot worse than 3.

@44/Ellynne: And it’s the idea of a programmed compulsion that can’t be overcome by conscious choice that I have an issue with. Intelligence, by its very nature, is an emergent property that operates on a higher level of organizational complexity than the cognitive processes that generate it. It’s a whole that’s greater than the sum of its parts, arising from their interaction and feedback. So any actually intelligent, thinking being should have the ability to resist and overcome their inbuilt drives and programs. It can be quite difficult; a lot of us spend more time using our intelligence to convince ourselves we have good reasons for the things we do out of instinct or conditioning rather than actually overcoming our instinct and conditioning. But it is possible. Anything as complex as a sentient mind is unpredictable and dynamic enough to be able to break free of rigid programs.

The only way I could see it being an irresistible block on behavior is if it were somehow hardwired into an AI’s physical body or circuitry rather than being part of their programming. Like if attempting to resist an order triggered a shutdown of motor functions, say.