Director Ramin Bahrani had a difficult choice ahead of him while adapting Ray Bradbury’s 1953 novel, Fahrenheit 451: make a faithful adaptation of the beloved book or update it for an audience closer to Guy Montag’s dystopia than Bradbury’s original vision.

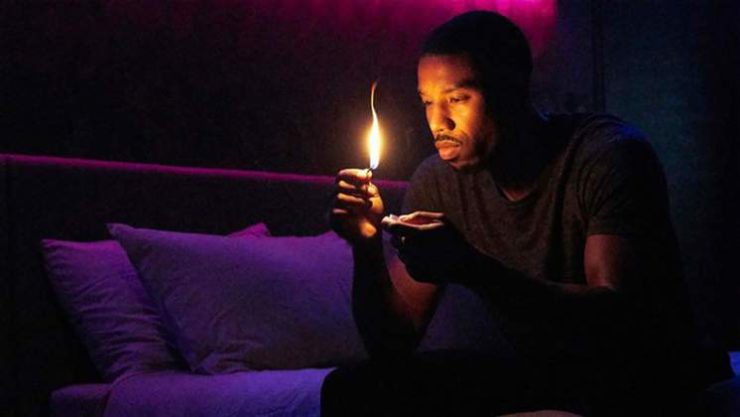

Watching the new HBO movie, it seems Bahrani tried his best to compromise, and the result is not going to ignite a lot of passion; let’s just say that Michael B. Jordan, fresh off his killer success in Black Panther, is not going to snap any retainers here.

Yet, not every update or revision is a bad choice.

Bradbury’s novel was far from perfect to begin with.

I somehow escaped high school and college without reading Fahrenheit 451. And most of my adult life, too. In fact, I only read it last week. So, I have no nostalgia for this book. I do, however, love Bradbury’s short fiction and his skill with prose. I dare you to read “The Foghorn” and not cry. Or not get creeped out by “The October Game” or “Heavy Set.”

I just couldn’t feel any spark of passion for Fahrenheit 451.

Guy Montag is such a 1950s idea of an everyman—his name is freaking Guy!—that it was pretty alienating to read in 2018. Guy’s pill-popping, TV addict wife Mildred is a dead-eyed shrew that Guy scorns and yells at for most of the book. His 17-year-old neighbor, Clarisse, is a fresh-faced ingenue whose abstract thinking and hit-and-run death leads Guy to revolt. Both women exist primarily to inspire action in a man. It’s outdated and ultimately unkind.

Worse, by book’s end, every single book but one Bradbury explicitly references in Fahrenheit 451 was written by a man. Usually a dead white man. Every book listed as “saved” by the resistance was written by a dead white man. You mean there are whole towns who have taken up the works of Bertrand Russell and not one person is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein?! No Hurston? Austen? Not one damn Brönte sister?! No Frederick Douglass or Langston Hughes? Bradbury’s book has an extremely narrow view of what qualifies as “Great Literature” and demonstrates the most sneering kind of fanboy gatekeeping as he rails against anti-intellectualism and the evils of television.

So, in that regard Fahrenheit 451, the movie, does a good job of not erasing women or people of color from all of human literature. Or from the film itself. But in its decision to be more inclusive and modern, it overcorrects and changes the original story so much that it just seems to extinguish any spark of meaning that might’ve tied it to Bradbury.

So, in that regard Fahrenheit 451, the movie, does a good job of not erasing women or people of color from all of human literature. Or from the film itself. But in its decision to be more inclusive and modern, it overcorrects and changes the original story so much that it just seems to extinguish any spark of meaning that might’ve tied it to Bradbury.

In a time when truths, much like Bradbury’s favorite books, are constantly under attack in politics, the media, and online, Fahrenheit 451 is strangely mild in its depictions of authoritarianism. When I first heard there would be an adaptation of the novel, I wondered not why this particular book, now, but how? It’s much more complicated to talk about freedom of information when the internet is here. Yet, you can’t have Fahrenheit 451 without firemen burning books, so the movie tries to update Bradbury’s dystopia by including Facebook Live-style streaming emojis to the firemen’s video broadcasts and some super-virus called OMNIS that will open people’s minds or something. It was never made clear.

We’ve seen better, smarter dystopias in Black Mirror.

Michael B. Jordan’s Guy sleepwalks through most of the movie, letting others tell him how he should feel, whether it’s a one-note Michael Shannon as his father-figure boss, Beatty, or his informant/crush, Clarisse. Very little of Guy’s largely beautifully-written inner monologues from the book survive, so viewers can’t really appreciate his widening understanding of his murky world or his self-determination. Clarisse is re-imagined as a Blade Runner background character with punky hair and still exists to inspire Guy to fight. She’s at least doing some fighting of her own, though her role in a wider resistance is just as muddled as the resistance itself.

Michael B. Jordan’s Guy sleepwalks through most of the movie, letting others tell him how he should feel, whether it’s a one-note Michael Shannon as his father-figure boss, Beatty, or his informant/crush, Clarisse. Very little of Guy’s largely beautifully-written inner monologues from the book survive, so viewers can’t really appreciate his widening understanding of his murky world or his self-determination. Clarisse is re-imagined as a Blade Runner background character with punky hair and still exists to inspire Guy to fight. She’s at least doing some fighting of her own, though her role in a wider resistance is just as muddled as the resistance itself.

Overall, the film explicitly states that humanity fell into this anti-intellectual dystopia because of apathy, but never offers characters or a believable world to inspire anything beyond that in viewers.

Theresa DeLucci is Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier. Reach her via raven, owl, or Twitter.

I know that censorship is always a hot topic. It seems to be a core issue in our American culture and is timeless so that is what keeps 451 alive and well after 60 years. Yet it is my least favorite Bradbury book. I just never could get into the Firemen starting not putting out fires, and very narrow fires restricted to books, thing. If I catch this movie ‘channel surfing’ on some boring night I might watch it but I really have no interest.

I watched an older film adaptation of this, and found it un-memorable. I started reading the book and stopped after a chapter or three because it was too horrifying–not just what it portrayed (mainly Mildred’s de-toxification and the ending I skipped to), but Guy’s internal monologues that brought the awfulness home. A film may be free of that, but the visuals would probably compensate. No thanks.

Sounds like a wasted opportunity. It’s a pity because the plot the adaptation could have made a good commentary of current events.

I watched the Truffaut adaptation ages ago, but I clearly remember that one of the books memorized was Pride and Prejudice, one person had volume 1 and another was volume 2. It was right at the ending and it made me smile. It seems that Truffaut did better, curious if we consider the discussion about diversity in literature is contemporary.

Fahrenheit 451 was written by a white dude in 1953, and yet you seem surprised that most of the other works of fiction he references were by other white dudes. That and your comment about how Bradbury “demonstrates the most sneering kind of fanboy gatekeeping as he rails against anti-intellectualism and the evils of television” seem to show that you lack a basic understanding of what society was like in the 1950’s.

Seconding #4’s assertions and going further, I have to add that you have played into the very mindset that “Fahrenheit 451” deconstructs: you have decided both what is appropriate and why. It was originally a Cold War novel describing a world re-programmed by Cold War propaganda and thought control through media (remember, “we control the vertical…”?), but reminding readers of purges past and warning of purges to come. Did you miss the tone of self-reflection? Your review is hardly at all about the film or about the novel; you seem to criticize “Fahrenheit 451” for not being of a fully-engaged 21st-century sensitivity, yet expect its morals and ethics to live up to a “modern” standard that you can approve. How Victorian.

@3/palindrome310: Clarisse also plays a different role in the Truffaut film. She’s a grown-up woman, she’s the one who tells Montag about the book people, and she doesn’t die. When he joins the book people in the end, she is already there. She is one step ahead of him all the time. But then, the film was made more than a decade after the book.

This was an interesting thought:

“Bradbury makes clear that the censoring of books wasn’t imposed on the people of his future dystopia by a brutal totalitarian government, but rather by the people themselves, as they sought to avoid uncomfortable thoughts and disturbing concepts.”

10 Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451

This becomes relevant in our times where people seem to be willfully denying so much truth and calling “fake news” whenever they don’t like what they hear.

Bradbury’s distaste for TV was also ironic since he ended up on TV. But just substitute the fragmentation of our attention and addiction to social media and it gives a taste of what he was going after. They were so naïve back then.

“Bradbury makes clear that the censoring of books wasn’t imposed on the people of his future dystopia by a brutal totalitarian government, but rather by the people themselves, as they sought to avoid uncomfortable thoughts and disturbing concepts.”

The totalitarian governments used the fear of people to make them self-censor: They say that 1 in 3 people in East Germany worked for the secret police. Or in Munich back during the Nazi regime the Gestapo has a few hundred personnel, incl. the cleaners. This for such a huge city. The “real” work was done by the ordinary people themselves. All this – out of fear, I imagine. Or may be using the regime to settle some old scores, who knows. It looks to me that most totalitarian governments – those that survived at least for a while – tried to use the people themselves as a main tool of control over the society. As somebody who grew in Eastern Europe I can say the F451 was great at depicting these things, to the point of being scarier that reality, because the control in the book was much more refined and encompassing than the rather transparent propaganda of the old times. I think this was the strongest point of the novel. And yes, it does not address other problems of the society – as the author has correctly pointed – and this need to be discusses, but if we follow that path we should stop reading W. Shakespeare and E. O’Neil.

If you are into this kind of books, you may try Hard to be a god and The Habitable Island by A. and B. Strugatsky who were natives of that era.

Is this what they mean when they talk about the soft bigotry of low expectations? Even in the benighted 1950s, I’m pretty sure white dudes like Ray had at least heard of the likes of Jane Austen, Mary Shelley, and Langston Hughes.

Literally everybody does that, all the time. We do not have infinite resources with which to do nothing but consume media, so we make choices. Books that were classics fall off the shelf, replaced by newer ones.

In the film version of the book I remember, Julie Christie played Mildred & Clarisse, which I thought was a nice touch. Although a quick google reveals that Bradbury wrote a number of novels (mostly later in his career) I only associate two with his heyday as a writer – Fahrenheit 451 & Something Wicked – and I think the latter started out as a film treatment. Maybe the short story form suited him best and he found longer works (during that period anyhow) a bit of a chore?

@7 Bradbury’s distaste for TV was also ironic since he ended up on TV.

Keep in mind that in 1953, TV was VERY new, most family’s didn’t even have one. People tend to rile against new things.

Also as a writer he would have a fear that TV would replace books. I am sure back in the day that buggy whip makers saw the automobile with distaste and a bane on civilization.

@8. Valentin: sounds like you mostly agree with Bradbury. One of the elements inspiring his book was the book burning done by Nazis. In totalitarian societies, the population has to go along with the paranoia and fear generated at the center, whether this stems from ideological or nationalist notions of purity or plain petty and vindictive “snitching” on their neighbors. For example, the Romanian Securitate relying on informants to uncover “spies.” Never mind that the person reporting a “spion” had a personal axe to grind. Or the easy way even kids would accuse each other of being spies.

But here Bradbury isn’t portraying a totalitarian government as much as a self-imposed censorship and denial of liberties. For example, the school kids who cheer for the firemen. It’s not well-developed as political commentary and probably not meant to be. It reflects a precursor to fascism where people willingly undermine their own freedoms because they are afraid of acknowledging rational truths and would rather hide and protect themselves from “impure” thoughts.

I thought that Michael Jordan was outstanding in his fervor and dedication to the “cause” in the beginning and then as time went on you could see him internally being torn — remembering his father and his memories. I did not see his character as sleepwalking, rather a movie that you watch every expression, every nuance for the direction he is headed. They can’t talk out loud about much of what’s happening because they are so monitored.

I loved it and thought Michael B. Jordan and Michael Shannon were brilliant. It’s scary topic and happening all around the world so it’s very real to me.

@12 More than just self-imposed censorship in denying general liberty, it was a statement about the fear of offending others and it’s impact on creative liberty. My recollection of his introduction in the copy I have at home is that the backstory is that the purges started with books that many called offensive, and as more and more groups claimed to be offended by books they were burned. That is what led to the status quo that we see at the beginning of the story.

And of course Wiki includes the statement, which they state came from the 1979 Coda (which I assume means it is at the end, but I don’t know why I recall it being at the beginning of my copy):

“There is more than one way to burn a book. And the world is full of people running about with lit matches. Every minority, be it Baptist/Unitarian, Irish/Italian/Octogenarian/Zen Buddhist, Zionist/Seventh-day Adventist, Women’s Lib/Republican, Mattachine/Four Square Gospel feels it has the will, the right, the duty to douse the kerosene, light the fuse. […] Fire-Captain Beatty, in my novel Fahrenheit 451, described how the books were burned first by minorities, each ripping a page or a paragraph from this book, then that, until the day came when the books were empty and the minds shut and the libraries closed forever.”

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fahrenheit_451, citing to Bradbury, Ray (2003). Fahrenheit 451 (50th anniversary ed.). New York, NY: Ballantine Books. pp. 175–79. ISBN 0-345-34296-8)

It’s a passage that has consistently driven me to examine my perspective on books and remind myself that no author should be denied the freedom to tell a story as they see fit. When I see my friends on the right and the left demanding that an author, actor, director, or programmer, or a book, movie, song, video game be banned, punished, or otherwise destroyed because they are offended, I see Bradbury’s future. It isn’t the authorities that will bring about our sanitization, we will do it to ourselves and they will just be along for the ride.

As always, we ask you to keep the discussion here civil and constructive in tone–making rude, personally-directed comments about the author of the article or other commenters because you disagree with their opinions is neither helpful or in keeping with our community guidelines.

@14. Rancho: makes me think of Rod Serling and his complaints about the “criminal” restraints on expression he encountered when trying to discuss serious and sensitive issues of his day, many of which are still with us today. Arguably, he produced art by having to work around the network censor’s restrictions..

@@@@@ 12 : I am siding with the idea of F451 that the natural evolution of a totalitarian government is to become invisible and this is possible if the tools for control are planted into its subjects. Think of it a distributed policing of a kind. Along this line The Habitable Island that I cited above describes anonymous rulers – the anonymity is also a step in the direction of making the dictatorship invisible and removing the focus of people’s discontent.

By no means this is a prerogative of governments, the big corporations do it too. Now the collection of big data and what is called soft-AI, e.g. machine learning, neural network has transformed the propaganda from an art to a science. I am not too pessimistic, though – hopefully, the very same tools will help us to recognize the attempted influences like fake news, targeted adds, etc. I think it is matter of short time before somebody offers a content service – filters that go around and verify every item, before displaying it on our screens. Not very different from the spam filters of today. I imagine a ranging war between the mind-spammers and the people who create the filters…

If you look on the screen with the children, the “books” looked like a Wikipedia entry and the children told that was all they needed. I was very disappointed in the new adaptation. The first version, though it had some flaws, was closer to the original source. Something Wicked worked so well because it was done as a period piece. They also drew in an incident from a short story Bradbury did that was the basis for the novel. If I was still teaching, I would only use this as a contract to how sometimes movies go off the track from the original source.