In August 1921, author A.A. Milne bought his one year old son, Christopher Robin, a teddy bear. This did not, perhaps, seem all that momentous at the time either for literary history or for large media conglomerate companies that used a mouse and a fairy as corporate logos. But a few years later, Milne found himself telling stories about his son and the teddy bear, now called “Winnie-the-Pooh,” or, on some pages, “Winnie-ther-Pooh.” Gradually, these turned into stories that Milne was able to sell to Punch Magazine.

Milne was already a critically acclaimed, successful novelist and playwright before he began writing the Pooh stories. He was a frequent contributor to the popular, influential magazine Punch, which helped put him in contact with two more authors who would later be associated with Disney animated films, J.M. Barrie and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. In 1914, he joined the British Army. In what is not, unfortunately, as much of a coincidence as it may seem, he was wounded in the Battle of the Somme, the same battle that left J.R.R. Tolkien invalided. The experience traumatized Milne for the rest of his life, and turned him into an ardent pacifist, an attitude only slightly softened during Britain’s later war with Nazi Germany. It also left him, like Tolkien, with a distinct fondness for retreating into fantasy worlds of his own creation.

Buy the Book

Winnie the Pooh

At least initially, however, fantasy did not pay the bills, and Milne focused mostly on plays, with the occasional novel, until he began publishing the Pooh stories in Punch in 1925. By 1926, he had enough stories for a small collection, simply entitled Winnie-the-Pooh. The second collection, The House at Pooh Corner, appeared in 1928. Both were illustrated by Ernest Shepard, then a cartoonist for Punch, who headed to the areas around Milne’s home to get an accurate sense of what the Hundred Acre Wood really looked like. Pooh also featured in some of the poems collected in Milne’s two collections of children’s poetry, When We Were Very Young and Now We Are Six.

All four books were instant hits, and Milne, whose agent had at first understandably argued with him about the wisdom of publishing collections of nursery rhymes and stories about his son’s teddy bear, found himself facing a completely different problem: the only thing anyone wanted from him was more stories about teddy bears. He refused, and—in a decision numerous lawyers were to benefit from later—sold the merchandising and most licensing rights to American literary agent and producer Stephen Slesinger, so that, later legend claimed, he would not have to deal with them.

Regardless of the reason, Slesinger’s marketing savvy helped make the already popular books even more popular. (As we’ll see, he was later to do the same for the Tarzan novels.) The public, adults and children alike, continued to clamor for more of Winnie-the-Pooh. Milne stuck stubbornly to plays, novels, and various nonfiction works.

It’s easy to see why the bear was more popular: once past the coy, slightly awkward introduction, Winnie-the-Pooh, is, as one of its characters might say, Very Good Indeed. Oh, certainly, a few matters need to be glossed over—for instance, just where does Pooh get all that honey (nine full jars in one story, which he easily consumes in just a few days)—and how does he pay for it? Why is Rabbit the only one of the characters to have an entire secondary set of friends and relations? Oh, sure, Owl mentions a relative or two, but we never see them, and I’m not entirely sure they exist. It’s certainly impressive that Owl can spell Tuesday—well, almost—but wouldn’t it be even more impressive if he could spell Wednesday—well, almost? And speaking of spelling, why can Piglet—not, we are assured, the most educated or clever of the characters in the woods—write a note begging for rescue when everyone else, including Christopher Robin, frequently struggles with basic spelling?

That said, it almost seems, well, heretical to say anything negative about a book that also has Pooh, the Bear with Very Little Brain; cowardly little Piglet who could be brave sometimes, and is secretly delighted to have people notice this; Owl, who can sorta spell things; busy, intelligent Rabbit; kindly Kanga and eager Roo; thoroughly depressed Eeyore, and Christopher Robin, who functions partly as a deux ex machina, able to solve nearly every problem except the true conundrum of finding the North Pole (and who, really, can blame him for that?) all engaging in thoroughly silly adventures.

When I was a kid, my favorite stories in Winnie-the-Pooh, by far, were the ones at the end of the book: the story where everyone heads off to find the North Pole—somewhat tricky, because no one, not even Rabbit nor Christopher Robin, knows exactly what the North Pole looks like; the story where Piglet is trapped in his house by rising floods, rescued by Christopher Robin and Pooh floating to him in an umbrella; and the final story, a party where Pooh—the one character in the books unable to read or write, is rewarded with a set of pencils at the end of a party in his honor.

Reading it now, I’m more struck by the opening chapters, and how subtly, almost cautiously, A.A. Milne draws us into the world of Winnie-the-Pooh. The first story is addressed to “you,” a character identified with the young Christopher Robin, who interacts with the tale both as Christopher Robin, a young boy listening to the story while clutching his teddy bear, and as Christopher Robin, a young boy helping his teddy bear trick some bees with some mud and a balloon—and eventually shooting the balloon and the bear down from the sky.

In the next story, the narrative continues to address Winnie-the-Pooh as “Bear.” But slowly, as Pooh becomes more and more of a character in his own right, surrounded by other characters in the forest, “Bear” disappears, replaced by “Pooh,” as if to emphasize that this is no longer the story of a child’s teddy bear, but rather the story of a very real Bear With Little Brain called Pooh. The framing story reappears at the end of Chapter Six, a story that, to the distress of the listening Christopher Robin, does not include Christopher Robin. The narrator hastily, if a little awkwardly, adds the boy to the story, with some prompting by Christopher Robin—until the listening Christopher Robin claims to remember the entire tale, and what he did in it.

The narrative device is then dropped again until the very end of the book, reminding us that these are, after all, just stories told to Christopher Robin and a teddy bear that he drags upstairs, bump bump bump, partly because—as Christopher Robin assures us—Pooh wants to hear all of the stories. Pooh may be just a touch vain, is all we are saying.

The House at Pooh Corner drops this narrative conceit almost entirely, one reason, perhaps, that I liked it more: in this book,Pooh is no longer just a teddy bear, but a very real bear. It opens not with an Introduction, but a Contradiction, an acknowledgement that almost all of the characters (except Tigger) had already been introduced and as a warning to hopeful small readers that Milne was not planning to churn out more Winnie the Pooh stories.

A distressing announcement, since The House at Pooh Corner is, if possible, better than the first book. By this time, Milne had full confidence in his characters and the world they inhabited, and it shows in the hilarious, often snappy dialogue. Eeyore, in particular, developed into a great comic character, able to say stuff like this:

“….So what it all comes to is that I built myself a house down by my little wood.”

“Did you really? How exciting!”

“The really exciting part,” said Eeyore in his most melancholy voice, “is that when I left it this morning it was there, and when I came back it wasn’t. Not at all, very natural, and it was only Eeyore’s house. But still I just wondered.”

Later, Eeyore developed a combination of superiority, kindness, and doom casting that made him one of the greatest, if not the greatest, character in the book. But Eeyore’s not the only source of hilarity: the book also has Pooh’s poems, Eeyore taking a sensible look at things, Tigger, Eeyore falling into a stream, Pooh explaining that lying face down on the floor is not the best way of looking at ceilings, and, if I haven’t mentioned him yet, Eeyore.

Also wise moments like this:

“Rabbit’s clever,” said Pooh thoughtfully.

“Yes,” said Piglet, “Rabbit’s clever.”

“And he has Brain.”

“Yes,” said Piglet, “Rabbit has Brain.”

There was a long silence.

“I suppose,” said Pooh, “that that’s why he never understands anything.”

Not coincidentally, in nearly every story, it’s Pooh and Piglet, not Rabbit and Owl, who save the day.

For all the humor, however, The House at Pooh Corner has more than a touch of melancholy. Things change. Owl’s house gets blown over by the wind—Kanga is horrified by its contents. Eeyore finds a new house for Owl, with only one slight problem—Piglet is already in it. In order to be nice and kind, Piglet has to move. Fortunately he can move in with Pooh.

Buy the Book

In An Absent Dream

And above all, Christopher Robin is growing up. In a middle chapter, he promises to be back soon. That’s true, but in a later chapter, he is leaving—even if somewhere in a forest, a little boy and his bear will always be playing. It’s a firm end; as Milne had stated in the beginning, he was saying good-bye to his characters.

And the right end, since above all, the Pooh books are about friendship. Pooh realizes that he’s only really happy when he’s with Piglet or Christopher Robin. Both attempts to get newly arrived strangers to leave—Kanga and Roo in the first book, Tigger in the second—lead to near disaster for the participants. Piglet has to—let’s all gasp together now—have a bath, and Rabbit finds himself lost in the fog, grateful to be found by a bouncing Tigger. It’s an argument for pacifism and tolerance, but also a celebration of friendship. They may have started as toys. They’ve since become playmates and friends. And that, I think, along with the wit and charm, is one reason why the books became such an incredible success.

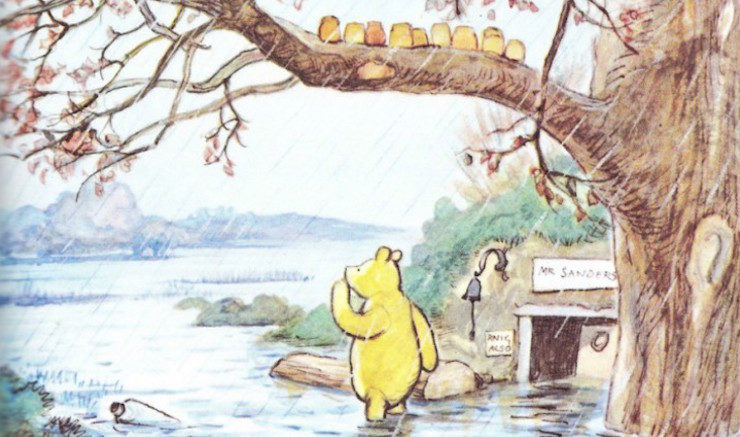

The other reason: the charming illustrations by illustrator Ernest Shepherd. His ghost would firmly disagree with me on this point, but the Pooh illustrations are among Shepherd’s best work, managing to convey Piglet’s terror, Eeyore’s depression, and Winnie-the-Pooh’s general cluelessness. Shepherd visited Ashdown Forest, where the stories are set, for additional inspiration; that touch of realism helped make the stories about talking stuffed animals seem, well, real.

Not everyone rejoiced in Winnie-the-Pooh’s success. A.A. Milne later considered the Pooh books a personal disaster, no matter how successful: they distracted public attention away from his adult novels and plays. Illustrator Ernest Shepherd glumly agreed about the effect of Pooh’s popularity on his own cartoons and illustrations: no one was interested. The real Christopher Robin Milne, always closer to his nanny than his parents, found himself saddled with a connection to Pooh for the rest of his life, and a difficult relationship with a father who by all accounts was not at all good with children in general and his son in particular. He later described his relationship with the Pooh books to an interviewer at the Telegraph as “something of a love-hate relationship,” while admitting that he was “quite fond of them really.” Later in life, he enjoyed a successful, happy life as a bookseller, but was never able to fully reconcile with either of his parents.

Over in the United States, Walt Disney knew little about the real Christopher Robin’s problems, and cared less. What he did see was two phenomenally popular books filled with talking animals (a Disney thing!) and humor (also a Disney thing!) This, he thought, would make a great cartoon.

This article was originally published in August 2015 as part of a series on rereading the source material for Disney Classics along with the films.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

I’m usually not one to leave comments, or to gush over authors, and I know this is a re-posted article, but all those caveats aside I just feel the need to say that Mari Ness is my favorite author on this site. I love how insightful, educational, and entertaining all of your articles are.

Great article!

The ending of The House At Pooh Corner always makes me cry.

I’ve still got the Winnie-the-Pooh that my mom bought for me at Sears when I was two :).

I always wonder- HOW did Pooh wind up living under the name of Sanders?

Last month, I had the extreme pleasure of visiting the “real-life” location of the Pooh stories, Ashdown Forest and specifically near Hartfield, UK. The journey there is a story all to itself, an American driver who rented a too-big car driving on TINY rural English roads on the “wrong” side. There were parts where we had to pull all the way to the side, rubbing the hedges at the side of the road, and fold up our right-hand mirror just to let a car pass. It was an adventure!

But the end of that adventure was the home of Winnie-the-Pooh, a set of trails in the “Five Hundred Acre Wood” where some of Christopher Robin’s real adventures took place, including the quarry where Eeyore lived, and many others. I went with my five-year old and he was positively in love with the walk. They’ve set up little houses along the way just like in the stories which you can find if your eyes are open and you search just a little way off the trail. We found Owl’s, Piglet’s, Pooh’s, and two or three houses that could have belonged to Eeyore.

The heart of the trail is the “Pooh Sticks Bridge” the original (?) bridge where a young Christopher Robin and his toy bear dropped pinecones into the stream and see which ones would come out the other side first.

I don’t want to know how historically accurate any of that is, or whether the bridge has been rebuilt seven times since then, but it is a lovely walk in a beautiful country. We had tea at a tea-shop (the first tea and crumpets for my American appetite!) nearby and it was an amazing capstone to an amazing trip. If you are a fan of the Pooh stories, especially if you have children that love the stories, I highly recommend making the trip. It is well worth the effort.

(Also not mentioned here is that the original Pooh stories have two authorized sequels but I am just reading them now with my son and I have not yet decided how they measure up to the much-loved originals.)

@3/PamAdams: Since the books are based on the real Christopher Robin Milne’s play with his stuffed animals, maybe the boy initially called the bear Mr. Sanders before settling on Winnie-the-Pooh, in that capricious way that small children have. (I seem to recall that he originally used the WtP name for a swan or something before it ended up attached to the bear.)

Christopher Milne’s own book depicts his mother as a simply awful woman, quite unintentionally I believe, and his father as shy, awkward and saddened by his difficulty connecting with his son. It seems to have been sonething they both worked at with never more than scattered momentary successes.

These books were a huge part of my young life, and Shepherd’s drawings will always be the touchstone for my imagining of the characters, not the cartoon versions. I love each of the characters for all their diverse personalities and quirks.

But off the top of my head, wasn’t it the East Pole they were searching for, and not the North Pole?

Is that a repeated typo, or is it actually called The House on Pooh Corner in the US?

@8: No, “The House at Pooh Corner” is correct–fixed!

@5 – The introduction to the first book says that Pooh’s original name was “Edward Bear” (and appeared in Milne’s poetry prior to the Pooh stories).

Pooh’s house being under a sign that says “Sanders” and Piglet’s being next to one saying “Trespassers Will […]” speak to the borrowed world that Christopher Robin made his own during his (fictional?) play. These details speak to us as a reader even as the characters themselves either ignore the anachronism or create their own stories about them. (Piglet’s, for example, is that a person named “Trespassers William” used to live at his house.)

@10

The original Winnie the bear was a resident in London Zoo, originally brought over the Atlantic by a Canadian WWI serviceman. Her name was a diminutive of “Winnipeg”.

Folks in New York City can see the original stuffed animals that Milne based Pooh, Tigger, Piglet, Eeyore, et al on at the New York Public Library on 42nd Street and 5th Avenue (the one with the lions out front).

https://www.nypl.org/about/locations/schwarzman/childrens-center-42nd-street/pooh

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

There are two excellent picture books written about Winnie that I’d recommend. Finding Winnie (2015) was written by Lindsay Mattick, a descendent of Captain Harry Coleburn, who rescued Winnie in Canada and took her to the WWI front! This didn’t work out too well and she ended up at the London Zoo. This book’s illustrator, Sophie Blackall, won the 2016 Caldecott Medal, the most distinguished picture book award out there.

A second title, Winnie: the true story of the bear who inspired Winnie-the-Pooh, was written by Sally M. Walker, an excellent historian and writer of kids’ books. This was also published in 2015, probably to take advantage of the WWI centennial.

On a personal note, my first two cats as an adult were named Pooh and Piglet. I’d been reading the books…

Should you ever get to New York City, the New York Public Library on 5th Avenue has the original Pooh, Piglet, Kanga, Eeyore, and Tigger on display.

https://www.nypl.org/blog/2016/08/02/welcome-back-winnie-pooh

Interesting that the original Winnie-the-Pooh/Edward Bear is a pretty standard “Teddy Bear” design, really quite an ordinary example of the toy design introduced by the Steiff company in 1903, with the articulated neck, shoulders, and hips and the stitched-on nose and mouth. I had a smaller, skinnier teddy bear of that type as a child, and I still have it — I tried to find out a few years back if it was worth anything, and I was able to figure out that it’s probably a 1925 Steiff model, but not rare enough or in good enough condition to have much more than sentimental value. I never realized how close a relative my “Ted E. Bear” (short for Theodore Edward) was to the original Pooh.

I suppose I can’t blame Disney for giving Pooh a more distinctive (and trademarkable) design, but I do have some regret that the Disney designs have overshadowed Ernest Shepard’s illustrations in popular awareness. But it’s interesting how the new Christopher Robin movie seems to be trying to combine/reconcile the Disney designs for the characters with the look and texture of the original stuffed animals.

I remember taking my young children into a certain independent bookshop and, whilst pretending to look at the displays, told them not to look round yet, but there was a tall grey haired man over there and in a moment they should turn idly and not stare.

Once we got out of the shop, I told them, “That was Christopher Robin”.

I loved Eeyore so very much, which, in hindsight, should maybe have clued my parents into my future troubles with depression.

*Cannot understand why the vision wanted to get slightly foggy while reading the part of the article that talked about saying good-bye to the characters*

Pooh’s stories are a treasure hoard of the most beautiful and/or insightful quotes I know. There aren’t enough words to express how much I adore them. I used one of these also once for my best friend’s birthday present, when I gave her an A4-sized photo of her and her horse with the quote “Some people care too much. I think it is called love.” This as well as so many others are genuine gems, so touching and brilliant.

I am happy to see that people share my love for Eeyore! I totally adore him, and have used a picture of him here-and-there as my profile picture for I cannot even remember how many years. (This might also be why I was thrilled and laughed out loud when one of my favourite characters in the Kate Daniels book series, Roman (who is a black volhv i.e. a good dark wizard in the books), was described in one scene wearing black pajama pants with Eeyore pattern.)

Also, Winnie-the-Pooh is reportedly the favourite of the amazing Japanese figure skater Yuzuru Hanyu. It seems that people know this, because during the last Olympics, when Hanyu ended his performance, the ice was literally yellow, covered with Poohs in all sizes :)

Also also, the kids in the Soviet Union grew up with Pooh and Piglet looking like this:

(I prefer the original illustrations)

(Edited to clean up the link)

Very thoughtful article. I understand where you were going with the introduction, but Mickey Mouse didn’t first appear until roughly the same time as Pooh and was not well known until the late 1920’s; and Tinkerbell wasn’t created or put in use as a logo for decades following.

It’s possible Rabbit and Owl were based upon real forest animals and that’s why their behavior and appearance can be a bit different than their plush companions.

@@.-@ Joe

I’m glad you enjoyed visiting the Ashdown Forest. One of my mum’s friends has a holiday cottage, and I remember staying there as a kid, and getting to wander round the woods.

I’m not sure if the bridge is the original, but you can play Pooh-sticks at any bridge with any old twigs or whatnot.

Chapter IX of Winnie-the-Pooh, In Which Piglet is Entirely Surrounded by Water, has my favorite long sentence of all time. It even recursively refers to itself as a long sentence. I read that as a kid and was never the same. It influenced both my own style and my reading preferences.

I always pronounce it “Winnie-ther-Pooh”, btw.

@21/William: “I always pronounce it “Winnie-ther-Pooh”, btw.”

Do you mean the American “ther” or the English “ther”? The latter is just the usual way “the” is pronounced in both forms of English, with a schwa instead of a long E sound.

A.A. Milne got into a feud with P.G. Wodehouse in the 1940’s. Wodehouse and his wife had been caught in France in 1940 during the Nazi invasion and had been sent to an internment camp. The Nazis offered to repatriate Wodehouse if he made propaganda radio broadcasts to England. Wodehouse, a true political naif, agreed, and made a few broadcasts. They were not pro-Nazi, but were rather flippant talks about the inconveniences of internment. Nevertheless, Wodehouse was condemned by many in England, including many fellow-writers, the most outspoken of whom was Milne (who was perhaps trying to make up for his earlier pacifism and anti-war positions in the 1930’s). The result was one reason why Wodehouse eventually relocated to the US. Wodehouse eventually got back at Milne in his 1949 short story, “Rodney Has a Relapse,” in which a thinly-disguised version of Milne appears as a hack writer of detective stories who gets fame and fortune from a series of terribly twee stories and poems about his son, who’s known as “Timothy Bobbin.” The character is depicted as a base opportunist who only sees his son as a gold-mine of inspirations for his work. It’s arguably the most genuinely “vindictive” thing Wodehouse ever wrote.

I don’t believe the “Some people care too much” quotation was in the original Pooh stories. One of the Disney versions, perhaps?

The oddest thing I’ve seen ascribed to Pooh was a line from Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Little Princess. Can’t even imagine how that happened.