Readers of a certain age may remember the excitement stirred up when various physicists proposed to add a third category of matter to:

- A. matter with zero rest mass (which always travels at the speed of light), and

- B. matter with rest mass (which always travels slower than light).

Now there’s C: matter whose rest mass is imaginary. For these hypothetical particles—tachyons—the speed of light may be a speed minimum, not a speed limit.

Tachyons may offer a way around that pesky light-speed barrier, and SF authors quickly noticed the narrative possibilities. If one could somehow transform matter into tachyons, then faster-than-light travel might be possible.

Granted, that’s a very big ‘if’ and, for reasons explained in this essay, tachyon drives are NOT a means of travel I’d ever use. But hey, the siren song of narrative convenience overrides all the wimpy what-ifs. Sure, getting every single elementary particle comprising the spaceship to transform simultaneously (whatever simultaneously means) could be tricky, but who wouldn’t risk being turned into goo if one could avoid spending decades or centuries travelling between stars? Fred Pohl’s Jem used tachyon conversion to get his near-future humans to a nearby star and the adventure awaiting them there.

Of course, even if tachyons didn’t permit faster-than-light travel, they might facilitate faster-than-light communication. Perhaps it would still take decades to get anywhere interesting, but at least one could talk to other entities on distant worlds. Sometimes, as in a Poul Anderson story whose title escapes me, this could facilitate doomed romances across distances too vast to cross. With a high enough bandwidth, one could even remote-control rented bodies, as postulated in Pohl and Williamson’s Farthest Star.

Farthest Star also explores the notion that one might record someone’s molecular pattern and beam it to a distant location, to be reconstituted there upon arrival. If one didn’t destroy the original while scanning it, one might even be able to create duplicate after duplicate to engage in high risk missions…

That’s all very well for the original. The copies might have a different perspective.

Any faster-than-light travel or communication also has the drawback (or feature, depending on your perspective) of allowing travel or communication with the past. Which leads to some interesting possibilities:

- This could change history: all efforts at reform, for instance, could be annulled by any fool with a time machine.

- Perhaps we would find that history is fixed, and we’re all puppets dancing to a pre-ordained script.

- Or perhaps time branches, in which case it sure is silly to have spent as much time as you did making important decisions while different versions of you were embracing all conceivable options.

The classic example of an intertemporal communication plot would be Gregory Benford’s Timescape, in which a scientist finds out what happens when one beams information into the past. I am not saying what happens, but it’s not happy. (Well, perhaps from a certain point of view…)

A 1970s paper whose title I have forgotten (and spent hours of poking through Google Scholar to find, and failed) drew my attention to another possible application, one that any M/m = edelta v/exhaust v-obsessed teen must have found as exciting as I did. IF we had a means to eject tachyons in a directional beam, we could use them to propel a rocket!1

Now, these tachyon-propelled rockets couldn’t break the speed of light—though they might get close to it. Regardless of the means of propulsion, the ships themselves are still subject to relativity, and nothing with a rest mass that is not imaginary can reach the speed of light. But what they could do is provide extremely high delta-vs without having to carry massive amounts of fuel.

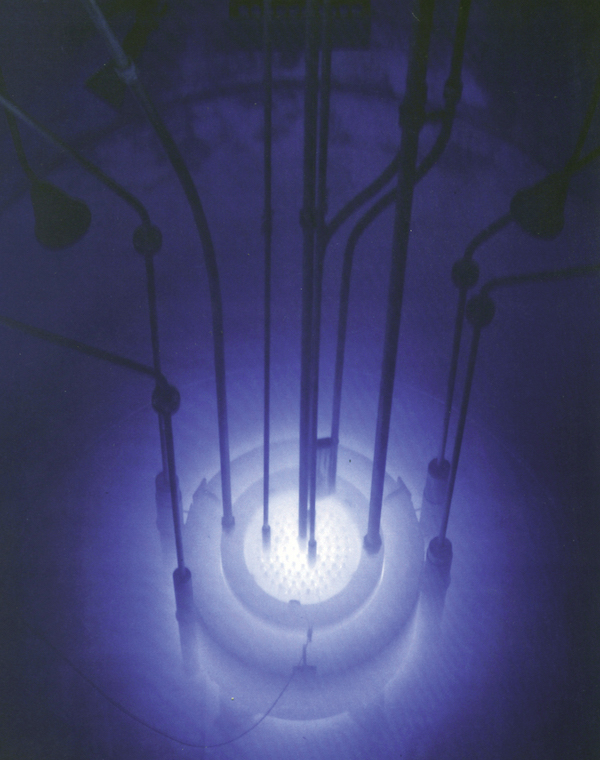

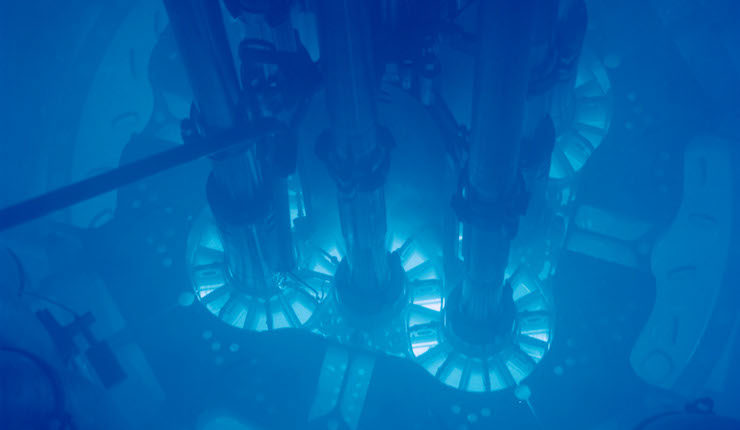

And the very best thing? If the tachyons emit Cherenkov radiation, then tachyon rockets would emit that blue glow seen in so many cinematic magical mystery drives.

Tachyon rockets are therefore ideal from the perspective of SF writers2. They are, in fact, a replacement for our lost and lamented friend, the unrealistically effective Bussard ramjet.

Curiously, aside from one essay by John Cramer, and one novel, Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War 3, if SF authors did leap on the narrative potential of the tachyon rocket, they’ve been doing so in books I have not yet read. Pity.

Top photo courtesy Argonne National Laboratory.

1: In some frames of reference. In other frames, it would look as if the beam were pushing the ship. Agreeing on what happened and in what order it happened becomes problematic once one adds FTL to the mix—good news for people like me, who have trouble keeping tenses straight from one end of sentence to the other.

2: Well, there are a couple of minor catches. One is that there is no evidence that tachyons exist. Some might go so far as to say the evidence suggests they don’t. As if “there is no evidence this stuff exists” ever stopped SF authors from using wormholes, jump drives, or psychic teleportation. Also, some models suggest any universe that has tachyons in it is only metastable and might tunnel down to a lower state of energy at any moment, utterly erasing all evidence of the previous state of being. Small price to pay for really efficient rockets, I say.

3: “Wait, didn’t they travel faster than light in The Forever War?” I hear you ask. They did, but not thanks to the tachyon rockets. Ships circumvented vast distances by flinging themselves headlong into black holes (called collapsars in the novel). As one does. In The Forever War, this was not a baroque means of suicide; ships did re-emerge from distant collapsars. So, a slightly different version of wormholes. The tachyon rockets in the novel provided the means to get to the black holes, which were often inconveniently far from the destinations humans wanted to reach.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.

Forget tachyons, I want to know where is my cold fusion and room temperature superconductivity!

Oh, superconductors. Want some superconductor-related drama? Here!

What about of Land of the Lost?

Is that the TV show? I’ve never seen it.

@2, My Grandpa used to make semi-conductors. I’m not at all sure what they are or what they do. Poor Grandpa, I didn’t inherit any of his tech savvy.

@@.-@, Land of the Lost was a Saturday morning live action show by Sid and Marty Kroft.

I know I am an old guy and it has been a LONG time since I have been in school but the couple of Physics classes I took I distinctly remember being taught that NOTHING can travel faster then the speed of light. Yes I know if you want to get from point A to point B faster then is capable under that rule that it might be possible to ‘trick’ your way past by various methods, such as worm holes, folding space/time etc. Are Tachyon’s one of these tricks that allow us to break that basic rule, and if so how?

Well, it’s not clear that they do or that if they do they’d interact with our sort of matter or if they did interact with our sort of matter the consequences would not be utterly catastrophic, from causality violations to the total annihilation of the universe. And they’re still subject to not being able to ever reach the speed of light. It’s just that for a tachyon, C is the lower limit of their speed, not the upper, because their rest mass is imaginary.

Thing I Did Not Know Before (thanks, Wikipedia!) :

“The X-Men character Silver Samurai has the power to generate a tachyon field which can cut through everything but adamantium by channeling his mutant energy into anything, usually his katana“.

My understanding of the math is that, due to messy singularities, nothing with a non-zero mass can travel AT the speed of light. Getting from speed<C to speed>C without speed==C left as a handwave for the author.

sdzald: IIRC, tachyons make mathematical sense in terms of the theory of relativity, but that doesn’t mean they exist in the real world, where there’s no evidence of anything having imaginary mass.

It sounds as though they’d be a way to keep relativity and still give up causality (in the “causes precede events” sense), whereas writers at least seem to daydream about going faster than like but keeping causality.

Tachyons, if they exist, could never go _slower_ than light.

Even though I have a BS in physics, I’ve never understood the Timescape hypothesis that tachyons would travel backward in time. After all, if you plug a velocity term greater than c into the Special Relativity equations, you get imaginary time flow, not negative. And even if you did get negative time flow within an FTL ship relative to an outside observer’s reference frame, that would just mean the observer would see time moving backward inside the ship, so that its crew would be younger when they arrived at their destination in the future, not that the ship would actually move into the observer’s past. So is there something about the physical meaning of imaginary time that I’m missing, or did Benford just fudge the physics?

ChristopherLBennett @12:

No, I don’t think Benford fudged the physics. The basic idea actually goes back to a paper by Einstein in 1907. Benford and two collaborators wrote a paper about it in 1970, arguing against a claim by Richard Feynman that one could dodge the potential paradoxes by assuming a particle traveling back in time was the same as its antiparticle, traveling forward (described a bit by Benford here).

There’s a Wikipedia article about it (“Tachyonic Anti-telephones”, taking its name from the title of the paper by Benford et al). If you look at it, you can see there are two velocities at issue: the subluminal velocity difference v between two inertial reference frames, which goes in the square root, and would indeed produce “imaginary time” if v > c (but it’s not); and the potentially superluminal velocity a, which is not inside a square root, and gives you a negative time result if a is > c.

@13/Peter Erwin: Okay, that makes sense. My grasp of the math has gotten quite rusty from disuse, but that equation looks simple enough for even me to parse.

There was one other thing that didn’t seem quite right to me when I first read Timescape, though. IIRC, the assumption seemed to be that if you sent a tachyon signal to where Earth was located in space X years ago, it would arrive there X years ago. That seems to be assuming that the tachyons’ temporal regression rate just happens to be exactly right to cover the appropriate distance in exactly that amount of negative time, which seems like quite a coincidence. Wouldn’t they be just as likely to go back in time at a higher or lower rate, so that they’d pass through that point of space long before Earth was there, or long after? The assumption that it always just exactly lined up was confusing to me too. I re-read the book sometime within the past couple of decades, no doubt with an eye toward seeing if I could figure out that question, but I’m afraid I don’t remember whether it made any more sense to me that time.

Was the Poul Anderson story about star-crossed lovers “Ghetto” or perhaps a related one in the same milieu. In “Ghetto”, a worker spacer who travelled for decades at a time and an aristo woman who was on a single trip fell for one another. Spacer was minded to give up his way of life (and family/tribe/clan/union) to marry the woman, but decided not to as her relatives and friends were deeply unpleasant.

Pfft, just find a narrativium mine and you’ll obtain the catalyst needed to punch through that annoying discontinuity at the speed of light. Easy!

@12: I can totally see how someone reading a description of the tachyonic antitelephone while skimming over the math might come away with the impression that it is the tachyons, rather than the information, moving backwards in time; it certainly sounds sciencey enough to justify that behavior as a fundamental property of a fictional universe! As for imaginary time, perhaps it is less a statement about how time flows in the tachyonic realm than a reminder that it is separated from our sub-c realm by a singularity, similar to the way that the imaginary parts of a quantum wave equation reflect limitations on our knowledge rather than observable phenomena of their own.

No, it wasn’t Ghetto. I am totally blanking on the title but the basic plot was a guy carrying on tachyonic communication with a woman on another world, FTL finally appearing and the grand romance the protagonist was convinced would be his going nowhere. It’s a plot that turns up in a few variations in Anderson. See also The Man Who Counts and, um, “The Star Plunderer”?

It would be pretty easy to put together She’s Just Not Into You: Tales of Doomed Romance by Poul Anderson. Sometimes she prefers the rich guy, sometimes the emperor, sometimes a jilted witch’s curse dooms her, sometimes she’s been dead for the whole novel. Sometimes working for the red menace leaves the protagonist impotent. There are lots of ways for Anderson’s leads not to get the girl.

ChristopherLBennett @@@@@ 14:

I’m afraid it’s been much too long since i read Timescape, so I don’t recall any of those details. Perhaps if the people generating the tachyons are able to specify their velocity, they can tune that to make things match up.

Ian @@@@@ 16:

might come away with the impression that it is the tachyons, rather than the information, moving backwards in time

Well, it is the tachyons moving backwards in time, when viewed in the correct reference frame. (Otherwise, how does the information get conveyed?)

Star Trek Voyager already molested the little particle.

Since we don’t see tachyon objects, either tachyons can’t be seen, or there are no tachyons, or we don’t know what they look like and some things that we see really are tachyons. Or I’m not a physicist. To be honest, I’m not really. But still!

There is a “Space: 1999” episode where IIRC a female crew member is cynically romanced by a stranger who turns out to be from a backwards-time parallel universe which is devolving instead of evolving and he intends to fix this at some cost to our universe, but I think that was a case of anti-matter. Like most “Space: 1999” episodes, the universe survived but the characters in the story didn’t fare well.

I’m perfectly happy with Hyper drive, Warp drive, jump drive and stargates.

Four very explainable fictional technologies that have a very rich and diverse history.

This was done 3 years earlier by James Blish in Spock Must Die. Which also means, Kyle @@@@@ 20, that Star Trek was molesting the little particle long before Voyager.

@20 & 23: Also, The Next Generation and Deep Space Nine had already made numerous references to tachyons before Voyager came along. TNG: “Redemption, Part II” established a tachyon grid between a couple of dozen starships as a way to detect cloaked Romulan ships crossing the Klingon border — presumably because you needed some kind of FTL beam or field traveling between ships to make the grid effective over many square light-years. But later Trek writers took to using tachyon scans as just a generic way to detect cloaked ships, and even started saying that cloaks emitted tachyons when they were deactivated, which seems like it’s missing the point of the original tachyon detection grid idea, that it was an active scan sending out tachyons rather than a passive scan detecting them.

There’s also TNG’s “inverse tachyon pulse” in “All Good Things…” creating the insanely stupid phenomenon called “anti-time,” and DS9’s “Explorers” postulating that “tachyon eddies” could somehow push a solar sail into warp space. So it’s not as if Voyager was the first Trek show to do questionable things with tachyons.

I think once the Star Trek writers glommed onto tachyons, they ruined it for everyone else. Their bad balognese “science” became associated with the term and no self respecting writer could use it afterwards.

Oh wait, I think doctor who writers might still embrace it, but I don’t think that’s going to help hard science fiction writers either.

When? A few minutes ago.

@19: Well, yes, the direction of the interval will certainly be frame-dependent. But much of the paradox depends upon how the sequencing of the signals is observed in a given reference frame, leaving the time behavior of an individual tachyon somewhat ill-defined. These sorts of details are exactly where the mathophobes (which seems to include at least a plurality of writers, unfortunately) glaze over and glom onto the idea “hey, a physicist just said there are these particles called tachyons that travel faster than light because they go backwards in time” and run with it while the physics-minded go “uh, wait a minute, that’s not quite what she meant…”.

Now…a tachyon emitter producing particles matching those envisioned in the tachyon antitelephone is gonna give miscreants the ability to go mess with past causality, or at least cause vehement arguments about who is responsible for a given event (both in-universe and on the internet), so maybe it would be better to abandon them in favor of some way to just tunnel through the c barrier to travel to where we want to go. However, that would seem to require not only that the ‘tachyon realm’ be some sort of weird version of hyperspace, but also that travelers endure some sort of transporter-like scanning + particle conversion to get there, so I suspect our illustrious host would not like the idea one bit…

@25/Braaainz: Trek used so many random subatomic particle names, most of them made up, that I doubt “tachyon” stood out from the crowd in people’s minds. At least it’s a real term that has a much, much longer and broader history than its occasional Trek use.

@27/Ian: I think you’re forgetting that Gregory Benford is an actual working physicist, and he based Timescape on his own theoretical work on tachyons. So there’s no doubt that he got the math right.

@28: No doubt. I’m referring not to Benford specifically, but SF writers in general, and my own experience from post-movie/TV discussions in grad school with people who do know the math or physics being perfectly willing to put the details aside if the rest of the story is good enough.

@5 If your statement about not knowing what semiconductors are was sincere, it represents the height of irony: you posted your statement as a message using a machine that absolutely requires semiconductors to function.

I can’t help but disagree with the assumption that tachyons are are plausible solution.

I believe the “current science” is that tachyons cannot interact with anything on this side of the light barrier (anything at or slower than c) so you’ll have hard time using them for anything practical. You’d have to find some way of cheating and getting tachyons to influence something observable.

They’d be a problem though, doing so would break the universe!

No matter how you go faster than light, you still have the causality issue. You end up arriving before you left.

The reason is space and time are linked together in Einstein’s spacetime. You could think of it as time itself spreads out from a point at C, so if you go faster than C, you are moving faster/backward in time.

So if you figured out how to influence anything with tachyons, then you’d influence the past, and open up that horrible can of worms.

Long story short, if you want to write “realistic” sci fi, then stick to the light barrier; and maybe pass on tachyons for now.

You obviously haven’t read enough sci-fi, it’s been loving tachyon’s for a long time in some famous books, The Forever War by Joe Haldeman is one excellent example.

Also Cherencov drives on starships have been used by multiple writers.

@16/Ian,

Why make it so complicated? Just reverse the polarity!

@22/Todd Adams,

It’s interesting how seemingly early on the trope developed that the jump, warp, bounce or whatever wasn’t so difficult, it’s navigating under those conditions that’s difficult. Some sort of metaphor for the use of the imagination?

@25/Braainz,

Given that Tachyons are so hard to understand, I wonder if on The Orville they just call them … oh, never mind.

Finally, what about using Quantum Entanglement to send messages faster than the speed of light? Isn’t that actually being done?

I feel embarrassed to even be asking that. But it seems to me that claim was being made in the news.

IIRC, which I may not, the ships of L. Neil Smith’s Tom Paine Maru used reflected tachyons to travel at FTL speeds.

Keleborn, thanks to quantum weirdness, they’ve succeeded in proving there must be some connection between entangled particles that operates instantaneously (what disapproving Einstein condemned as “spooky action at a distance”), but you can’t send messages that way: it’s all random noise. The only way to show the correlation existed is to send a message the slow way round and confirm that yes, they were entangled after all.

Sorry, no tachyons.

It isn’t hard to show that you can extract energy from tachyons without reducing their energy. Violations of conservation of energy are a no go condition.

@37/pjcamp: Tachyons don’t have to be real to be usable in science fiction. SF is based on “What if?” scenarios, so you just have to ask, “What if tachyons were real?” and you have a story. What James is wondering is why tachyon drives aren’t as popular in fiction as other conjectural FTL methods.

@35/del,

Thanks for clarifying that.

@37/pjcamp,

Seems to me that tachyons (if they exist) and normal matter effectively occupy two different universes, and if under some conditions they could tunnel between universes (becoming something else on the other side), they’d be transferring energy between universes, and total energy would be conserved.

Not that I’m claiming to know what I’m talking about. It’s just a thought.

I think I remember reading somewhere that Jonathan Frakes invented a new class of particles for Star Trek, the “tetchyon”, by virtue of mispronouncing the mentions of tachyons in a script. It caught on and the goto particle for everything on TNG was tetchyons for a while.

@40/nelc: I think you must be thinking of tetryons, a fictional type of subspace particle introduced in TNG: “Schisms.” The word was first spoken in the episode by Data, then Picard, then Crusher, and then LaForge before Riker ever uttered it, and it was spelled “tetryons” in the script, so it wasn’t a mispronunciation. So whatever you read was egregiously in error.

“Tachy-gone House Cleaning! Purge your home of inconvenient tachyons, sir?”

Knock knock “Who’s there?”

@42/del,

Tsk, Tsk. Tacky.

@32: when you have a chance to read the article you’re replying to, you may notice a contribution from Joe Haldeman. And Cherenkov didn’t just drive the ship, he also beamed down to planets with the Captain and Mister Spock.

@35: there is real quantum message encryption that I think involves entanglement, but it doesn’t send a message FTL, it just prevents eavesdropping somehow. I think it uses the universe as what’s called a “one-time pad”.

@40, 41: I gather that Next Gen contributing writers would say ” – tech – ” in the script and the production script editor would fill in the required gabble.

@50: how dare you. Do I come here and talk about your mother? Well, if I will, it’s going to will have been your fault!

@44/Robert Carnegie: I’ll assume you’re joking about “Cherenkov” there. As for your third point, the “TECH” lines in the scripts were filled in the shows’ technical consultants Rick Sternbach and Michael Okuda, or their science consultants including Naren Shankar and Andre Bormanis, or their medical consultant Denise Okuda, or whoever was appropriate to consult. At the time of “Schisms,” Shankar was the science consultant, so “tetryon” was either his coinage, Sternbach’s, or Okuda’s.

Faster than light communication doesn’t mean time travel – it just means special relativity is wrong.

True, but the problem there is, special relativity keeps taking on all comers and punching their lights out. Turning it into a contest between ftl and special relativity makes it likely ftl will be the loser.

@46&47: Well, the reason it’s called Special Relativity is that it’s limited to a specific, simplified case of unaccelerated motion. It’s not wrong, just incomplete by design. Once you broaden the math to encompass accelerated frames of reference, as in General Relativity, you can get things like spacetime warps and wormholes if you plug in extreme enough variables. You still run into causality problems, though, and physicists generally assume that the universe just wouldn’t allow such paradoxes to happen, but it could be that it allows for them (by time being immutable or by the branching off of parallel timelines).

Of course, with that kind of ESL (effective superluminal) travel, you aren’t actually moving faster than light relative to local space as a tachyon would, just moving at normal tardyon speeds through a cosmic shortcut. So you wouldn’t have to move back in time, although you could. A lot of the time, the “backward in time” interpretation is just based on the relativistic approach of defining when things happen by when an observer detects the light from them, so if you outrace the light, your perception of the order in which things happened would be the reverse of that of an observer at your destination. But that wouldn’t really become a paradox if it were just a one-way trip. There are cases where FTL travel could end up getting you back to your starting point before you left (a closed timelike curve), but it depends on the particular situation.

I wonder to what degree more effective use of tachyons in SF is hampered by the softness of the term itself: tachyon refers not to a type of particle with well-defined properties (e.g. electron) but rather to a family of particles (cf. fermion) weakly constrained merely by a lower bound on their allowed speeds. On the science-fantasy end this gives authors lots of freedom, but the results often end up indistinguishable from made-up particles; harder SF would seem to require a more thought-out theory, but that could lead to infodumps that bog down the story for something only introduced to justify how travel or communications can occur at the speed of plot.

Perhaps a good middle ground is to invent plot-convenient particles and refer to them as ‘tachyonic’, which acknowledges the science without really committing to anything too specific. Bonus No-Prize for authors whose spacefarers discuss switching between the ‘tachyonic’ and ‘bradyonic’ drives for different legs of the journey.

@49/Ian: Good point. If tachyons did exist, then specific particles of the class would probably be given distinct names. It’s sort of like my feeling about the term “dark matter.” It annoys me a bit when SF characters in the far future talk about dark matter nebulas or dark matter drives or whatever. The only reason we call it “dark matter” is because we don’t know what the heck it is so we don’t have a better term for it. It’s basically “Terra Incognita” for particle physics. Once we figure out what kind of particles the stuff is actually made of, we’ll probably start calling those particles by their name and the placeholder term “dark matter” will go away.

Although then it would be tricky to convey that to a present-day audience, except by a clumsy construction like “I’m detecting a field of thingyons — you know, what they used to call ‘dark matter’ centuries ago, even though I have no reason to bring up that obscure bit of trivia in this context.”

@44/Robert Carnegie: “Well, if I will, it’s going to will have been your fault!”

Is this the Future Semiconditionally Modified Subinverted Plagal Past Subjunctive Intentional?

@48: Minor nitpicking. Special relativity can handle accelerated motions; it just takes calculus (integration) rather than algebra to do the calculations. For example, the relativistic rocket equations can be derived with special relativity (as Forward does here http://www.relativitycalculator.com/images/rocket_equations/AIAA.pdf) for example. Einstein even correctly calculated gravitational time dilation in 1907, well before he had developed general relativity – all it required was special relativity and the equivalence principle; general relativity required another several years of work.

I was talking to Poul Anderson. I don’t remember how tachyons came into the conversation. But I said used the Fatal Word.

Poul said, “Oh, I would never be a tachyon. It would be so much nicer to be a classyon.”

One more for the Poul Anderson relationship that doesn’t happen list– a story where a male telepath and a female telepath make brief contact with each other…. and when they have more time together, they find they can’t stand each other. Telepaths are rare, people who aren’t reeking with self-hatred are rarer.

I’m not convinced FTL radio (an “ansible”) isn’t possible given two key constraints: Both ends of the conversation must be in the same inertial frame. Anything with rest mass is limited to less than c, as always.

Those constraints seem to allow a form of FTL that can’t break causality.

And the first one offers plot points, since you can’t talk if you can’t match frames. If one was being chased, for example, one can’t call for help easily

@Gerry_Quinn Faster-than-light travel means time travel, but only in to the future.

I don’t think it’d allow traveling into the past, but if you are in an environment separated from observation from any other particles then you will be able to put yourself in a situation where particles are moving more slowly in that environment which essentially is “traveling” into the future – since time would be much slower inside as opposed to outside.

This seems like a lot of extrapolating, but if you are doing faster-than-light-speed travel then I think this kind of environment is most likely necessary for it to be safe anyway?

@55 & @56: Here’s a page that attempts to explain it. It doesn’t matter whether you send particles or a signal: the result is still “FTL, Special Relativity, Causality – pick (at most) two”.

Of course we can’t dispense with causality, so the result is that we must choose between special relativity and FTL.

Physics without special relativity would be far from completely up-ended. We would have an inertial frame of reference for the vacuum (as was assumed to be the case up until a century or so ago). The big question would be how come known particles never seem to communicate / travel faster than light, however thermodynamically favourable it might be! If we could make tachyons, surely the processes that make them would also be accessible to ordinary particle interactions. But if we found out how to make tachyons, I suppose we would know the answer to that one.

In such a world, only someone at rest with respect to the vacuum could state with certainty that the plane of simultaneity perceived by them has all events (including FTL-correlated events) in the correct order.

Once again Quantum Mechanics comes to the rescue. The uncertainty principle, if I understand it correctly, allows for both causality and conservation of energy to be violated in a sufficiently small time interval. So you can still travel faster than light, as long as you’re not picky about where you go or when you leave. :)

I can’t add much to the physics discussion, but I can report one SF use of tachyons that has stuck in the memory for a quarter of a century: Margaret Goff Clark’s novel for children, The Boy from the UFO Returns (1981). Also known as Barney in Space. One of my childhood faves.

It’s the one with Tibbo, snow, several close brushes with death by skiing, a trip to the moon, a bad guy called Rokell and aliens who look like swarms of golden needles when they’re not taking human form… if that helps.

I’m almost definitely certain that said aliens flew said UFOs faster than light thanks to tachyon drives. But I haven’t read it in about twenty-five years, so…

(It was also a sequel, so the first book may have mentioned them as well. But I never found or read that one, much to my disappointment.)

@57: Yes, I’m quite familiar with “pick two.” If you work this out on a spacetime diagram, it’s very easy to see how FTL permits access to the past. However, if two points are in the same inertial frame, instantaneous communication is “flat” and doesn’t violate causality in any way I can see. It’s when one frame is moving with respect to the other that problems occur.

FWIW, I’ve written about this in more detail on an old blog post along with spacetime diagrams illustrating the issues and why I believe an ansible might work so long as both frames matched.

@60: The problem is that if SOME people in the universe move, the paradox is inescapable. Consider two grids of observers, with all the observers in each grid in constant positions with respect to each others, but the two grids are in relative motion. The observers in each grid keep in contact with each other by ansible. They use only light speed signals to contact observers in the other grid.

Now when two observers meet, light speed signals are instantaneous anyway. So if the grids are dense enough, they can both keep in instantaneous contact, because whenever observers in the two grids meet, they can instantaneously update each other on observations in their own grid, and transmit the data from the other grid by ansible to all those in their own. So any paradox arising from giving relatively moving observers ansibles will still apply!

BTW, I see I never linked the page I intended to a few posts ago! Here it is:

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Special_Relativity/Faster_than_light_signals,_causality_and_Special_Relativity

@61/Gerry Quinn: But isn’t information moving backward in time only a paradox if you assume it would allow changing the past? If the timeline is fixed, then the information arriving in the past would just be part of a closed causal loop of the sort that’s actually permitted by physical law (as in the Novikov Self-Consistency Principle). Indeed, there’s John Cramer’s transactional interpretation of quantum mechanics in which “advanced waves” coming back in time from the future are a routine part of quantum physics, the reason that particles seem to “know” what the outcome of a slit experiment will be, for example.

Really, the only reason we think of effect preceding cause as a paradox is because it conflicts with our common-sense assumptions of how causality should work. But tons of things in physics defy common sense, because common sense is based on the narrow range of physical conditions we experience on Earth and thus doesn’t work for extremes of velocity, gravity, energy, etc. In physics terms, something is only a paradox if the math doesn’t add up, if there’s no single, consistent solution to the equations that describe it. And as Novikov showed, the equation for a time loop, an event that causes itself to happen, does resolve mathematically. It works because it doesn’t contradict itself — the time travel causes the events that lead to the time travel (as in the movie 12 Monkeys, say, or Interstellar), rather than the usual fictional device where the time travelers change their own past or prevent their own existence.

So you could potentially have FTL travel or communication, as long as it was in a universe where time was immutable, where someone going back in time would be part of what “always” happened rather than a change to the “original” history. As for people having foreknowledge of future events and being unable to change them, that would conflict with conventional assumptions of causality, but it would work mathematically and physically. We’d just have to accept that free will is limited when time travel is involved, that freedom of choice is contingent upon not knowing the outcome in advance.

@61: … D’Oh! You’re absolutely right, of course. Just needed someone to point out the flaw in my thinking. That grid example did the trick. I’d never considered multiple observers in two frames before. One can diagram the situation with just four observers, two in each frame…

Say Al and Bob are in one frame separated by distance but communicating by ansible. Mary and Nancy, also share a frame, also separate, also communicating by ansible, but in relative motion to Al and Bob such that Mary’s path intersects Al while Nancy’s intersects Bob.

What is simultaneous to Al and Bob, a moment when Mary passes Al and Nancy passes Bob, isn’t to Mary and Nancy. To them, Nancy might pass Bob before Mary passes Al (or vice versa).

Which would certainly screw with causality!

At least I conditioned it with “I’m not convinced.” But I am now. No ansibles

Never shoulda doubted Ol’ Al. He’s been right every time. (Which makes me think quantum gravity might not be a thing, but that’s a whole other discussion.)

@62: I would say quantum non-locality, which has been proven to exist but transmits no actionable thermodynamic information, is actually the strongest argument against any kind of self-consistent / self-maintained time bubble. Everything in such a bubble still has to be connected by quantum interactions to the rest of the universe, so a discontinuity of that kind should have negligible probability.

@63: Personally I think special relativity is probably right, but I find general relativity unacceptable as a fundamental theory. It’s just very accurate under normal conditions. I would say it breaks down around the event horizon of black holes, and the interiors are not as described by it. Even those who think black hole interior solutions are valid must accept that general relativity leads to singularities, which are surely an indication that something is wrong.

@64/Gerry_Quinn: I don’t understand. How can self-consistency be a discontinuity? That’s a contradiction in terms.

I think you’re missing my point. My proposal is not any kind of “time bubble” — it’s that the entire universe is temporally immutable. Information from the future coming back to the past is not a paradox, because it doesn’t allow changing anything. It’s just part of the sequence of events. If transactional quantum theory is correct, it’s happening constantly already.

The Novikov self-consistency principle asserts that this is true in classical terms — that the only time travels the universe would permit are those that are mathematically self-consistent, where the sequence of events that results from the time travel’s effect on the past is the same sequence of events that led to the time travel in the first place. The standard example is a ball falling through a wormhole, coming out in its past, and knocking itself into the wormhole. That time travel is allowed because it changes nothing. What isn’t allowed is the ball knocking itself away from the wormhole, because that’s self-contradictory and the math doesn’t resolve.

There are also quantum arguments for self-consistency which are discussed in this Scientific American article. Basically, by going back in time, you correlate the past with your present and thereby guarantee that your present will occur.

So both classical and quantum physics say that time travel is physically allowed as long as history is immutable. There’s no paradox, because every event still only happens one way. The time travel doesn’t alter what happened as in Back to the Future — it was always part of the cause of events in the first place, as in 12 Monkeys or Interstellar. The only thing that’s contradicted is our narrow human expectation of how cause and effect occur. But relativity already proves that’s an erroneously limited view of reality.

It’s been a while since I read The Forever War but are you sure about the tachyon rockets? Their only appearance that I remember was as an infantry heavy weapon.

Pretty sure, from passages like this:

@65: I have no problem with advanced interactions etc. However, the non-local quantum multiverse is not the same as our observable entropy driven world. Indeed, the idea of a single predictable outcome of events is somewhat antagonistic to it.

Consider a time loop in flat spacetime. We (observers external to the time loop) see an object or information going backwards in time. What this means is that from our perspective we are seeing the backward portion of the time loop as a region of decreasing entropy, in conflict with the second law of thermodynamics (and therefore also quantum theory as generally understood). At the earliest point of the loop it merges with the forward portion of the loop. So what we outside observers see is the time loop region suddenly splitting into a forward and backward portion, for no prior reason at all. And under ordinary assumptions, both parts are correlated with the surrounding environment in the usual way, which ought to lead to the prevalence of classical observable histories due to decoherence – yet this weirdness happens. This is what I mean by a discontinuity.

You might say, this is like just like a photon splitting into a virtual electron and positron, which then rejoin – this is certainly something that happens all the time in usual models. But that happens without a decrease in entropy. A time loop that carries ponderable information backward must have a negative entropy region.

Now if you believe in non-simple spacetime topologies (personally I don’t) you can perhaps make an argument that such things could occur. I would myself see it as just another reason not to believe in such topologies!

@68/Gerry_Quinn: But we don’t see the information going backward in time, since it’s doing so inside a wormhole or some other exceptional spacetime distortion. We just see it show up in the past and affect events, and then, after a certain interval, we see it transmitted into the time warp.

Also, the Second Law of Thermodynamics does not forbid entropy from decreasing anywhere. We decrease local entropy all the time by doing work. The law just says that the total entropy of a closed system must increase. The entropy of localized parts of that system can decrease as long as there’s an increase in entropy elsewhere in the system. As long as the future and the past are interacting with each other, then they’re parts of the same overall system, i.e. the universe.

Anyway, let’s not forget that we aren’t talking about real physics here, we’re talking about fictional universes and whether they can plausibly have FTL without creating time paradoxes. My point is that if you posit a fictional universe where time is unalterable, then that lets you have FTL, because any time travel that results would be unable to change things and thus would not create a paradox. You’d just have to limit yourself to time travel stories based on the idea of time being unalterable, rather than ones based on changing history. Or you could go with a many-worlds version where time travel could split off a parallel timeline where things happen differently while the original timeline persists unchanged. In short, if the objection to FTL in fiction is that it would create time paradoxes, then an immutable timeline solves that objection. And it has the virtue of being consistent with the theoretical models of physicists like Novikov and Deutsch.

Another potential way to avoid time paradoxes is to posit that tachyons (and whatever information or mass-energy they are conveying) emitted from one reference frame can only interact with a finite range of other reference frames. For example, the tachyonic antitelephone only starts flipping the (apparent) time order of events when the tachyons’ speed exceeds a particular threshold calculable from the two observers’ relative velocity; if the ‘coupling strength’ declines with increasing tachyon speed per a law that causes it to vanish at or before that critical threshold, then tachyonic communication between reference frames is squelched and the paradox is avoided.

Would such a formula represent a ridiculously ad-hoc trick to avoid potential causality issues, a bit of mathematical sophistry? Of course!! But remember that things like the universality of c for all observers and the quantization of photon energies were similarly introduced as kludges—and were initially viewed as such—until the weight of empirical evidence forced us to rewrite the laws of physics to elevate such counter-intuitive hacks into fundamental principles.

When creating a fictional universe, it is easy to will into existence the ‘empirical’ data required to justify the inclusion of some cool, speculative particle or phenomenon. What sets the better stories apart is the simultaneous inclusion of some compensating law that (mostly) limits the scope of the effect to its plot-convenient aspects—and it is especially helpful if such a law is baked into the story’s premise (whether or not any explicit mention survives the final edits) early enough in the writing process to prevent plot holes or the technobabble that attempts to explain them away.

@69: Indeed, I didn’t mean to clip the wings of any SF writers who intend to include time travel; I would hope if anything to give them ideas of what to break, or examples of objections which will leave the objectors dumbfounded when confronted with an actual working time machine! And of course some of the objections could inspire plot ideas.

As for the issue of distorted spacetime, I did say that non-simple spacetime topologies (spacetime distortions that are topologically incompatible with a flat background) are a way around some of the problems. My view is that quantum theory is fundamental and general relativity is not, and that such spacetimes cannot occur – though I concede that that opinion is far from universal.

Of course SF would be nearly as badly off without wormholes as without simple FTL!

FWIW, those things in harder SF that are non-factual and unexplained (or casually hand-waved away) — such as FTL — I’ve long termed a “gimme.”

As in, “Gimme FTL, and I’ll tell you a good story.”

Cause the whole deal about SF is that there’s always gonna be at least one gimme. The fiction in our science! :)

The “1970s paper whose title I have forgotten (and spent hours of poking through Google Scholar to find, and failed) drew my attention to another possible application, one that any M/m = edelta v/exhaust v-obsessed teen must have found as exciting as I did. IF we had a means to eject tachyons in a directional beam, we could use them to propel a rocket!”, probably, appeared in the science anthology *Ahead of Time* (Doubleday, 1972) edited by Harry Harrison and Theodore J Gordon. Alas, I cannot provide the author’s name or the article’s title. My copy of the book is locked away in storage. This is the earliest paper or discussion I know of on the subject of tachyon rocket propulsion. The timing is right for Joe Haldeman to have seen it and included the concept in *The Forever War* (1974).

Further research is a wonderful thing. I found the article on tachyons in *Ahead of Time* (1972) and its author. Viz., “What are Tachyons, and What Could We Do With Them?” by G. Feinberg. The very fellow who coined the name of the concept. He was also the first person to propose the tachyon rocket concept. It definitely should be better know by science-fiction authors.

Thank you very much!

In addition to Jeff’s reference (which I read back when it was new), see this 1993 article from Analog by John Cramer:

http://www.npl.washington.edu/AV/altvw61.html