When I worked in eldercare, both in assisted living facilities and in a nursing home, people who found out I was a novelist would often say things like, “Lots of material around here,” or “Do you write about your work?” I would always smile wryly and say no, my writing is pretty much unrelated.

I write epic fantasy. My characters swing swords, cast spells, and alternately wield or try to evade divine intervention. With a single memorable exception, they do not have dementia or even act particularly irrationally. Most of the time, the connection between my writing and my work wasn’t nearly as obvious as people apparently imagined.

But there is a connection. Writing fantasy helped me build a particular set of problem-solving skills that I used in my work day in and day out. To explain how, I’m going to have to tell you a bit about best practices in dementia care.

First off, dementia is an umbrella term. It does not describe a single disease or disorder, but a set of symptoms that could have any number of causes. In that sense, I have always thought of it as similar to pneumonia: pneumonia just means that your lungs are full of something and therefore less effective. Whether that something is fluid resulting from a bacterial infection, a virus, a near-drowning, or the aspiration of food and drink, the symptoms and dangers are similar enough that we use the same term to describe them.

Similarly, dementia-like symptoms can be caused by all sorts of things: dehydration, lack of sleep, chronic stress, interaction with certain medications, traumatic brain injury, stroke, long-term effects from alcoholism or other chemical addictions, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and many lesser-known and less common causes and manifestations. You’ll notice, though, that this list can be separated into reversible causes of delirium, like dehydration or chronic stress, and irreversible ones like Alzheimer’s disease (it’s generally only the irreversible causes that are classified as dementia, for all that the symptoms can be identical). To date, we have no cure for Alzheimer’s, let alone Parkinson’s, Lewy Body, Huntington’s, Korsakoff syndrome (the form often related to alcoholism), or vascular dementia. In eldercare, these are the dementias we work with day to day.

So how do we manage an incurable disease? With humanity. We recognize that these are progressive, degenerative diseases, and that a person whose brain is shrinking and dying will not be able to inhabit our reality for long.

That’s not a metaphor; I’m not talking about mortality. I mean that our shared understanding of how the world works, how space and time function, is a world apart from what a dementia patient can understand and relate to. The idea that winter is cold, or that one does not leave the house naked (especially at that time of year!), or that a person born in 1920 cannot possibly be just four years old in 2018 – none of these are necessarily obvious to a person with middle- or late-stage dementia. As a result, our usual instinct to insist that winter is too cold to go outside naked, that a person born in 1920 must be nearly a hundred years old by now, becomes intensely counterproductive. What we might think of as “pulling them back to reality,” a person with dementia experiences as gaslighting. When we insist on impossible things, all we can accomplish is to piss somebody off.

Or worse. I once worked with a woman whose daughter visited nearly every day, and every time she asked where her husband was, the response was, “Dad died, mom. Two years ago.”

It was the first time she had heard that devastating news.

Every time.

In dementia care, we try to teach people not to do that. Your insistence on a certain reality cannot force people to join you there and be “normal” again. There are no magic words that will cure a degenerative brain disease.

What we do instead is to join people in their realities. If you’re a centenarian and you tell me your mother is coming to pick you up from school soon, I might ask you what you feel like doing when you get home. Play cards? Why, I have a deck right here! We can play while we wait for her!

And that’s where the connection to writing fantasy comes in, because an in-world problem must always have an in-world solution. Just as my characters won’t be treating their prophetic visions with Zyprexa or Seroquel, you can’t soothe a person who’s hallucinating or paranoid by telling them they’re wrong about everything.

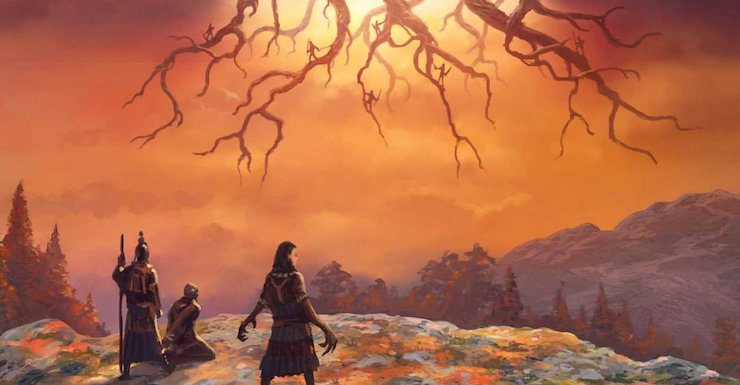

Buy the Book

A Breach in the Heavens

I worked once with a lady whose father had been a minister, whose husband had been a minister, who responded to stress by raining fire and brimstone upon the unbelievers. She told me that one of our nurses, Eric, was trying to steal God but that God would crush him under His foot. Oh sure, he was laughing now, and he’d laugh and laugh and laugh all the way to the Bad Place. She yelled at everybody who wasn’t taking Eric to jail that they would be sorry, and of course when other residents yelled at her to shut up, the trouble only escalated.

Medicines are useless in such a context: nobody could have gotten this lady to take anything when she was having a fire-and-brimstone moment.

But in-world problems have in-world solutions.

I told her I believed her. I told her we should leave Eric to his fate and get away from him, God-thief that he was. I walked her back to her room and listened for half an hour or more while she poured her heart out, telling me, in some combination of English and word salad, about the evil that had befallen her. I just sat there and listened, nodding, validating, letting her feel heard, until she had gotten it—whatever it was—off her chest. Then we walked back together and she sat across from Eric once more, newly calm and magnanimous.

Most of us will deal with dementia at some point in our lives, if we haven’t already. It’s a scary place to be sometimes, and a wondrous place. I’ve seen music transform someone completely. I’ve been told that Jesus was standing right behind me.

When you do find yourself in fantasyland, remember: it’s easier to sell love potions than medicine.

N.S. Dolkart is the author of the Godserfs trilogy: Silent Hall, Among the Fallen, and A Breach in the Heavens, which is out now from Angry Robot Books. He spent eight years working in eldercare, six of them at a skilled nursing facility, directed a memory care unit, and has trained front-line staff in dementia care best practices. He is now a very happy stay-at-home dad.

This is lovely, and kind, and humane, and it certainly makes me want to read your books.

My father-in-law passed before my mother-in-law, who was in a nursing home for Alzheimer’s. We told her one time when he died, and then after that did not. He was always “coming soon, I’m sure.” She looked for him and waited, but did not pine, nor did she grieve. Much more kind than constant reminders.

I think the point here is that suspension of disbelief is like … treating dementia? The reader and author together agree that this story will have its own reality: here are its rules, and these are the available solutions to its problems. I wonder what potential there is in this perspective, to describe the best ways to augment that experience for the reader? What are the “love potions” and the “medicine” in that context?

@1. I would like to echo Mary Beth’s comment. As I was reading I thought “this is so humane.” As soon as I finished reading I went and looked you up. Looking forward to reading your books.

My heart is bursting! If only people approached everyday with this point of view, regardless of the population they will encounter! What a wonderful world it could be!!

My grandmother was in her nineties with dementia when her little mutt died, and it was really tragic. There was no way we could produce a dog and it took her a lot of work for her to remember something day-to-day, so we spent a lot of time sitting her down and gently explaining that her dog had died and comforting her. It was hard on her and it was hard on us, but reality didn’t let us live in her fantasy. Eventually, she accepted that her dog was gone, and we got a young rescue dog to watch over her. She also adopted my dog as her own (although he was black and white, and her dog had been brown, so she was not confused that this was a second dog).

Thank you for this wonderful, knowledgeable, compassionate essay. It does make me want to read your books, too.

Noah – Great article and how very true. Before my mom passed, she had ‘episodes’ of dementia (most of the time she really was ‘with it’) and it certainly did not do either of us any good to argue about the ‘truth’ when she had her own sense of reality. Your kindness and compassion show how much patience you have – you should be proud of yourself at work, at home and also as an author!!!

Wow, this ties right in to a long article just published by the New Yorker (which I read a few hours ago).

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/10/08/the-comforting-fictions-of-dementia-care

Apparently your approach (which I heartily agree with) can be controversial.

When a friend spoke of the daily trauma of re-telling her dad (who had dementia) that her mom had died, I knew immediately that I could never do that to anyone.

In regards to the “New Yorker” article, which I just read (and thank you for the link, Nancy McClure) – I…don’t know. I think there is a difference between setting up expensive, elaborate simulations of the past and choosing not to hurt someone over and over by telling them every day that their loved ones are dead. I’m also not THAT kind of doctor, but I think/hope that medical doctors involved in dementia cases know the distinction between “lying” to a patient when the truth could make a difference, and when someone is too far gone for the truth to be anything but painful and, potentially, actually harmful.

I’ve never had to experience a relative having dementia (although one of my worst nightmares is experiencing it myself or, maybe even worse, seeing my mom develop it). I apologize PROFUSELY in advance – I know it is SO FAR from the same thing and I don’t want to be offensive – but I have a cat, who has lived with my partner and me for over 15 years, dying of kidney failure right now. She doesn’t understand that her kidneys have failed and I can’t explain that to her in any way that she would ever understand. All we can do is keep her as happy and and comfortable as possible by giving her medicated food and IV fluids and taking her to the vet for check-ups. (And she is currently curled up against me as I’m typing this – she still gets around well and enjoys being petted.)

The only way I could make her “understand” what is happening to her would be to stop her treatment and let her be in pain, which I would never EVER EVER do. Again, I am NOT trying to say that human beings suffering from dementia are AT ALL close to the same as a chronically ill cat, but I think there is a point at which we may have to make a decision about what hurts and what helps someone. I understand the history of doctors sometimes misinforming or lying to their patients, but I really believe that when someone can’t make decisions for themselves, medical professionals and the other people in their lives have to decide what is best to do to minimize their suffering.

Thank you for this article