Now that Jeff LaSala’s excellent Silmarillion Primer has reached the Downfall of Númenor, I’d like to talk about something that has been bothering me about the whole Númenor matter:

How on earth did the Númenóreans become such good mariners?

“Above all arts,” says the Akallabêth, the Men of Númenor “nourished ship-building and sea-craft, and they became mariners whose like shall never be again since the world was diminished; and voyaging upon the wide seas was the chief feat and adventure of their hardy men in the gallant days of their youth.” With the exception of the Undying Lands, travel to which was banned, the Dúnedain traversed the Sundering Sea and beyond: “from the darkness of the North to the heats of the South, and beyond the South to the Nether Darkness; and they came even into the inner seas, and sailed about Middle-earth and glimpsed from their high prows the Gates of Morning in the East.” In other words: they got around.

To travel the world like that doesn’t just require hardy seafarers and ships, it requires skilled navigation. And that’s where the problem is. Before the Changing of the World that destroyed Númenor bent the seas and made the world round, the world—Arda—was flat. And if you know enough about maps, navigation, or mucking about with boats, you know that will have serious implications for navigation.

Think about how a sailing crew would navigate on our world. During the later years of the Age of Sail, a navigator might make use of a compass, a sextant and a marine chronometer to figure out their precise location on a map—the compass to determine bearing; the sextant to determine the latitude from the height of the Sun at noon or Polaris at night; the chronometer to determine longitude. (Longitude can be determined by measuring the difference in time between noon in two locations: if local noon is an hour earlier in one position than it is in another, it’s 15 degrees west of that other position.) Earlier in maritime history an astrolabe or a Jacob’s staff would have been used instead of a sextant.

All of these tools are predicated on a spherical (okay, oblate spheroid) world. On a flat earth they wouldn’t work the same way, or even at all. On a flat earth, noon takes place at the same time around the world—Arda has no time zones—so longitude can’t be determined that way. And while the angle of the Sun or the celestial north pole might change the further north or south you go, it would not (as we will see) be a reliable way of determining latitude.

So how could the Númenóreans have navigated? That’s a surprisingly tricky question—one I didn’t think would have a good answer when I started working on this article. But it turns out that there are methods they could have used to cross the wide seas of Arda without getting completely and hopelessly lost. In this thought experiment, I explore how they might have done it.

Sea-Craft in Middle-earth

But before we talk about navigating Tolkien’s seas, let’s establish what we know about them.

For all of the talk of Sea-Kings and of passing over the Sea, and for all the characters from Tuor to Legolas coming down with case after incurable case of thalassophilia, the Sea plays a relatively small role in Tolkien’s legendarium. In a 2010 essay for TheOneRing.net, Ringer Squire notes that Tolkien mostly keeps the Sea off-stage. “In the annals of Middle-earth there is no action at sea, no description of the moods of the ocean, no engagement with the voyages as voyages. Tolkien’s Sea for all its greatness is merely the context for a text about Lands.” It acts as both borderland and staging area: deeps for ships to come out of, like Elendil’s nine ships out of the wreck of Númenor, or to disappear into, like the ship bearing the Ring-bearers away at the end of The Return of the King.

As such, we have few details of the seafaring aspects of the cultures of Middle-earth, Númenor or Eldamar, because it’s not the central focus of the story. Even Eärendil’s pivotal voyage is dealt with in a single paragraph. Mostly we read about ships and shipbuilding: about Círdan the Shipwright, the swan-ships of Alqualondë, the vast fleets of the Númenóreans built to challenge the might of Mordor and (later) Valinor. The focus is on ships’ seaworthiness (Telerin ships are apparently unsinkable) rather than sailing prowess.

Artists working in the Tolkien legendarium generally depict small, open single-masted boats, with square or lateen sails. Most of them seem to have oars: Eärendil’s ship Vingilot had them, and in Unfinished Tales an approaching Eldarin ship was remarked upon for being oarless. The ships were not always small: Númenor in particular was capable of building gargantuan vessels. Aldarion’s ship Hirilondë is described in Unfinished Tales as “like a castle with tall masts and great sails like clouds, bearing men and stores enough for a town.” Millenia later, Ar-Pharazôn’s flagship Alcarondas, the Castle of the Sea, is described as “many-oared” and “many-masted,” and with “many strong slaves to row beneath the lash.” (Remember, kids: Ar-Pharazôn is bad.)

Either way, large or small, we’re talking about galleys rather than pure sailing vessels: boats that rely on muscle power when the winds fail or are unfavourable. Winds nevertheless play a major role in Númenórean seafaring: “Aldarion and Erendis,” a chapter in Unfinished Tales that includes more about Númenórean seafaring than any other source, describes riding the spring winds blowing from the west, ships “borne by the winds with foam at its throat to coasts and havens unguessed,” and being beset by “contrary winds and great storms.”

In dealing with those winds and storms there is a certain amount of divine intervention, or at least divine restraint, on the part of Ossë and Uinen, the Maiar responsible for storms and calm waters, respectively. As Aldarion’s father, Tar-Meneldur the fifth king of Númenor, remonstrates with him,

Do you forget that the Edain dwell here under the grace of the Lords of the West, that Uinen is kind to us, and Ossë is restrained? Our ships are guarded, and other hands guide them than ours. So be not overproud, or the grace may wane; and do not presume that it will extend to those who risk themselves without need upon the rocks of strange shores or in the lands of men of darkness.

Emphasis added in bold: the Dúnedain are not necessarily masters of their own craft.

How Could They Have Navigated?

Following the winds and the weather (and when they’re adverse, enduring them), is a rather passive form of sea-craft, and strange spirits lying in seas is no basis for a system of navigation. Surely the Dúnedain had more agency than that when it came to feats and adventure.

Fortunately, there are methods of finding your way at sea that could be used on a flat world. John Edward Huth sets out a number of them in his 2013 book, The Lost Art of Finding Your Way, which discusses the strategies by which pre-GPS human beings used to be able to avoid getting lost. Huth’s book is an argument for mindfulness and situational awareness: awareness of your surroundings, of the factors that may push you off course, and the tricks you can use to put you right again. For sea-based navigation, they include:

- Using wind direction as a natural compass;

- Following the migration paths of birds;

- Local knowledge of currents and tides;

- Local knowledge of the interference patterns in the waves created by nearby land; and

- Dead reckoning: using distance and direction travelled to estimate your current position.

Currents and winds and tides, a connection to the sea: these methods have a certain poetry, a certain lack of technology, a certain naturalness that would no doubt appeal to Tolkien’s anti-modern outlook, and were probably what he would have had in mind if he had given some thought to this subject. One imagines what Strider the Ranger would do at sea.

But are they enough?

It depends on where you’re sailing, and how far; but as far as the Númenóreans are concerned, no, they aren’t.

Each of these methods has a margin of error that gets larger the further you travel. The winds can change. Currents induce drift. Dead reckoning’s uncertainties—figured by Huth as between five and ten percent—accumulate over time, like an expanding cone. The further you go, the less accurate your path, the further off course you can get without knowing it. You need to get a fix on your actual position on a regular basis.

This is not a problem when navigating short or even medium distances. Significant error will not have time to accumulate: if you’re off by only a few miles, you can correct your course visually. And if your journey has many intermediate steps—if, for example, you’re hopping from island to island—you can get a fix on your position at every stop, increasing the accuracy of your overall route.

The Númenóreans, however, were sailing over large distances. How large? The maps in Karen Wynne Fonstad’s Atlas of Middle-earth come with a scale, so we can figure that out.

| To | Approximate Distance | Heading | Travel Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mithlond (Grey Havens) | 1,900 miles | NNE | 24 days |

| Vinyalondë (Lond Daer) | 1,700 miles | NE | 22 days |

| Pelargir | 1,800 miles | ENE | 23 days |

| Umbar | 1,600 miles | ENE | 20 days |

The ports in Middle-earth used by the Dúnedain were between 1,600 and 1,900 miles from the main Númenórean haven of Rómenna, on a roughly north-easterly heading. Ships in the early Age of Sail could average about eighty miles a day; using that as our benchmark, and assuming ideal conditions, it should take between three and four weeks to make the journey from Númenor to Middle-earth. Ideal conditions—and an improbably straight line. More realistically, a month would be considered exceptionally quick.

But the problem isn’t that it’s 1,600 to 1,900 miles. It’s 1,600 to 1,900 miles over uninterrupted ocean. The distance between Númenor and Middle-earth is roughly the same as the distance between Norway and Greenland, but the Norse never did that trip in one go: they could, for example, stop at Shetland, the Faroe Islands, and Iceland. There appear to be no islands between Númenor and Middle-earth, which means there are no intermediate stops for Númenórean ships to pause and reorient themselves. Nowhere on land to get a fix. The chances of drifting off course are quite high.

This isn’t much of an issue when sailing from Númenor to Middle-earth: Middle-earth is huge and hard to miss. If you were aiming for Mithlond and end up at Umbar instead, you can work your way up the coast and still make your date with Gil-galad. Getting back home is a little trickier: at 250 miles across, Númenor is a smaller target, though not particularly small. Assuming Huth’s five to ten percent uncertainty, the cone of uncertainty would be around 160 to 380 miles. It would be difficult for a seasoned mariner to miss that target, especially given the extended horizon of a flat world and the good eyesight of the Dúnedain. Plus there’s the Meneltarma: the mother of all trig pillars.

But wait! Huth’s five to ten percent uncertainty assumes the use of a compass. Do the Númenóreans even have compasses? We don’t know whether Arda has a magnetic field: it hasn’t come up in Tolkien’s writings, as far as I’m aware. Earth’s magnetic field is the result of its outer core acting as a dynamo: it requires planetary rotation. Because Arda is not round and does not spin, it won’t have a magnetic field—not unless one of Aulë’s Maiar is tasked with churning things up in the deeps. So compasses may not be a thing, in which case sailing past Númenor—and into trouble—just got a lot more likely.

So, our Númenórean navigators need to solve two problems: how to figure out a ship’s bearing, and how to get a fix at sea.

Bearing and Position

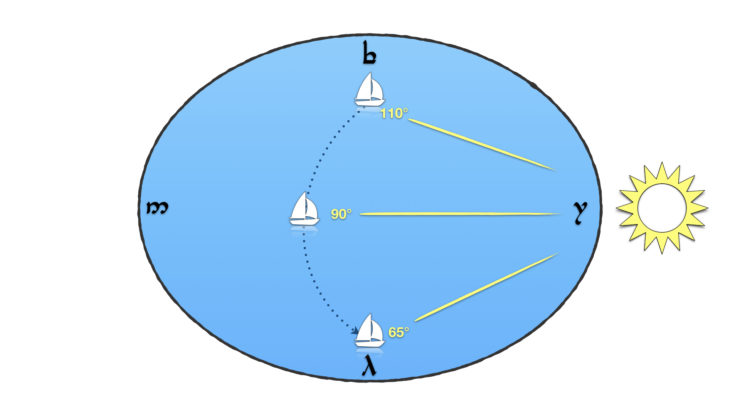

If magnetic compasses aren’t an option, the Númenórean navigators would have to resort to celestial methods to determine bearing. For example, the Sun. Even on Arda, the Sun rises in the East and sets in the West, and so sunrise and sunset can be used to determine a rough heading. But on Arda, because the Sun rises and sets at exactly the same point, the azimuth angle of the sunrise changes depending on your position, not just your latitude. A ship keeping the rising Sun to port would sail in a long arc curving from southwest to southeast, and the effect would be greater the further east it was. You could compensate for it, but first you’d need to know your exact position, and solving the problem would be more complicated over long voyages.

Something similar would occur if the navigators used the stars as their guide. We know that Tolkien’s celestial sphere rotates on its axis, because we’re told that Tar-Meneldur observed the motions of the stars from a tower in the north of Númenor. Enter star compasses. Based on the position of rising and setting stars, star compasses have been used both by Arab navigators in the Indian Ocean and by Pacific Islanders: at equatorial latitudes a star will rise at the same point, giving a consistent bearing. On a flat earth like Arda it should operate at any latitude, and the same equatorial stars and constellations would be useable, but there’s a catch: like the rising Sun, the azimuth of a rising star would change depend on your position. Borgil (Aldebaran) and Helluin (Sirius) would rise at a different angle relative to true north in Lindon than it would in Umbar, just as the Sun does.

Which means that the Númenórean navigators can’t determine an accurate bearing without knowing their position. So how do they determine their position? As I mentioned above, longitude can’t be determined by the Sun at high noon. Nor can latitude: the Sun would appear to have the same apparent altitude in a circle around the centre of the world, rather than along parallels of latitude.

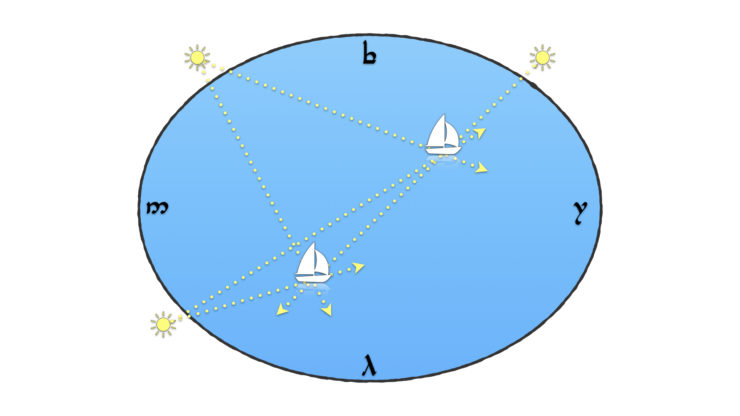

Since we’ve been talking about azimuth, a solution presents itself: triangulation.

You can’t do very much with the azimuth of the rising point of a single star. With a second star, or even the Sun, the observer is now at the intersection of two lines between themselves and the two stars—position lines. That gives the angle between the two stars. If the observer also knows the direction of true north (or west, or east), that would be sufficient to determine position, but on Arda, as we’ve established, we need to find position before we can find bearing. So we add a third star and a third position line. The angles between these three lines will be unique for every position on the earth.

This is similar to the intercept method still used in navigation today (as well as the method my computerized telescope uses to align itself). The intercept method combines position lines derived from celestial observations with more conventional means of navigation (the chronometer, the sextant, charts and tables) to achieve a high degree of accuracy. Since many of those conventional methods wouldn’t work on a flat earth, the Númenóreans wouldn’t be able to be quite that accurate. But it would be far more accurate than dead reckoning, and—more importantly—it would allow them to get a fix at sea.

I imagine it working something like this: In the same way that Ptolemy’s Geography or medieval astronomical tables collected longitude/latitude coordinates for cities in the known world, the Númenóreans would collect angles. Getting a fix at sea would involve taking new angular measurements and comparing them to what was already recorded. Perhaps there would be a set of tables carried by every ship’s master, or perhaps there would be a lot of math involved; either way, the new position could be interpolated into what was already known. But however it was done, it could be done. If nothing else, they’d have nearly three thousand years to get good at it.

This method yields two unusual outcomes. One is that because they’re measuring azimuth rather than altitude, Númenórean navigation instruments would be held horizontally; sextants, octants, and astrolabes are held vertically. And, as I suggested above, bearing would be derived from position. Once a navigator determines their ship’s position, they will know the angular difference between the position lines and the compass points: for example, that north is 80 degrees clockwise of the rising of Borgil at this location. It would be a good deal more complicated than using a magnetic compass, but more consistent, because magnetic declination wouldn’t be a factor.

But a significant drawback is that bearing could not be checked throughout the day: following a compass heading or a rhumb line wouldn’t be possible. You sail; at night you get a fix and see how far off course you’ve gone over the course of the day; you make corrections for the next day’s sailing. Which means that a Númenórean navigator requires clear, starry skies—if you’re beset by storms or clouds, your ability to navigate drops precipitously. In a cosmology where angelic spirits rule the winds and the waves and the skies, it really would behoove you to remain in their good graces.

The Changing of the World

Of course, everything changed with the Downfall. The mariners of the Dúnedain kingdoms in exile, Gondor and Arnor, would be starting from scratch. Ossë and Uinen would no longer be factors, and the stars would, from their perspective, behave strangely: they would be different if they moved too far south, and their angles would not change if they moved east to west. They would have to learn navigation all over again, on seas that operated under entirely new rules.

Small wonder the Exiles, who managed to, you know, circumnavigate the globe, nevertheless saw their Númenórean forebears as “mariners whose like shall never be again since the world was diminished”: they mastered lost seas in ways that were now forever obsolete.

Top image: “Mithlond” by Jordy Lakiere.

Jonathan Crowe blogs about maps at The Map Room and reviews Canadian science fiction for AE. His sf fanzine, Ecdysis, was a two-time Aurora Award finalist. He lives in Shawville, Quebec, with his wife, their three cats, and an uncomfortable number of snakes. He’s on Twitter at @mcwetboy.

Is there a reason they couldn’t have simply worked out direction from the North Star? Very simple to keep sailing a consistent bearing once you can see Polaris. Of course that doesn’t solve the problem of position-finding.

@1 ajay: Good question! As I see it, the problem with Polaris is twofold. One, parallax. Its position in the sky relative to true north would change as you moved from west to east. In Valinor it would be to the northeast; in the far east it would be to the northwest. How much it would change would depend on the distance between the stars and Arda: far enough away and parallax won’t matter. And over short distances it would not be a problem, because it would be consistent, and the margin of error would not have a chance to magnify over distance. It depends on how far you’re going, and how precise you need to be.

The other problem is that in ancient times Polaris wasn’t the pole star. If we accept Tolkien’s conceit that Middle-earth is our world in the distant past, then Polaris would not have been an option.

Nice Monty Python reference there…

“Dead reckoning. So called because if you don’t reckon it correctly, you’re dead.”

Entertaining as this is, the discussion of celestial navigation contains a subtle but potentially devastating flaw. If the Sun and stars are going around a flat world at a distance close enough for the azimuth of the rise (or set) point to have a measurable variation with ‘latitude’, then the altitude measurements of that object at different points in the day would also have a measurable variation with ‘longitude’; moreover, the rate at which objects moved across the sky would vary during the day in a manner that depended upon both ‘longitude’ and ‘latitude’ (e.g. those in Valinor would observe the Sun to set more quickly than it rose).

That means that, in such a world, the path of any celestial object would follow a unique pattern of altitude, azimuth, and time as seen from any given location…meaning it would be possible to fix one’s position (to some degree of accuracy based on the limitation of your chronometer and observing equipment) based on a single observation!

OT: an uncomfortable number of snakes

Am I the only reader interested in knowing the exact number and type?

They could just follow the currents toward the edge of the world, where all the water would be falling off. Or go upstream toward the center. If we assume the improbability of a flat earth, we could also assume that they had compasses that utilized “handwavium” or some other improbable element that would point them in the right directions.

The ridiculous implications of a flat earth are why mariners knew long before Columbus that the world was round.

A flat world surrounded by oceans needs a wall around it to keep the water in or have some way to replace the lost water.

“On a flat earth, noon takes place at the same time around the world”

Depends on how you define ‘noon’. If you define it as “the sun is overhead”, then by the Gates of Dawn in the Uttermost East, noon for you happens right after dawn. Also, you’re very hot. Arien will then get further and further away until dusk.

Which gets back to comment #4. If Varda’s stars and the Sun and Moon are close enough for parallax to work, which they might be, then you have lots of options for determining your position. (Assuming a spherical Arda is about 12,000 miles across, the stars might be 6,000 miles up. Or maybe closer; how fast does Earendil fly?) (Related tip: do NOT navigate by the Evening Star; King Elros’s father moves around.)

Needing to see the sky isn’t a unique limit; Earth mariners before compass and chronometer were equally crippled. Of course, they also didn’t go exploring open oceans that much.

Another aspect of a flat world is that line of sight isn’t limited by a curving horizon. It is limited by increasing mass of atmosphere diffusing light, but perhaps farsighted sailors could see useful landmarks. Of the Meneltarna: ‘It was the highest location of Númenor, and it was said that the “farsighted” could see Tol Eressëa from its summit’

@8, I was just going to cite the same observation about Meneltarna. I don’t see why getting higher up should let you see farther on a flat Earth, I suspect Tolkien made a mistake there.

Great discussion. The mention of math makes me remember that I don’t think we are ever told if math was studied among any of the peoples in Tolkien’s world. I would like to think the Elves and the Numenoreans were both very good at it, and not just for utilitarian purposes, but sadly Tolkien neglected to tell us.

@9 I’m guessing that getting up high means that you can see over any obstacles in the way. Numenor wasn’t flat, maybe that’s the only place where you could get actual line-of-sight to Tol Eressëa?

Maybe there’s more haze lower down near sea-level: the sea isn’t completely flat either (waves, etc), so maybe that’s an issue. If you’re six feet tall, standing at sea-level, a swell any more than six feet is going to obscure your vision in that direction.

I don’t see why getting higher up should let you see farther on a flat Earth

Well, ceteris paribus it shouldn’t, but remember that the air is denser and more humid lower down. You’ll be able to see through more miles of high-altitude air than sea-level air.

@9 Jr, @11 NotACat: I’m inclined to think mistake on Tolkien’s part: he may not have thought through all the implications of his cosmology, or worked it out consistently in his unpublished writings. For example, in “Aldarion and Erendis” (Unfinished Tales), Tolkien wrote this:

Which is not something that could happen on a flat earth.

@8 drs: If noon is defined as when the Sun reaches the highest point in the sky (and it usually is, viz., high noon), the time would be consistent across Arda. It would only be directly overhead along the equator, whether on a round world or flat.

@13: The Sun will be at high noon (transiting the meridian, to use the astronomical term) simulatneously for all observers on Arda (flat OR round) if and only if the Sun is far enough away for its light rays to be effectively parallel. But if that’s the case, then the same situation applies at sunrise and so all observers would view the Sun rising at the same azimuth—eliminating the viability of the parallax-based navigation method you describe above. If there’s parallax in the north-south axis, there must be equivalent parallax in the east-west axis, unless geometry itself works differently in Tolkien’s world.

@14: Oh hell, you’re right. If the Sun isn’t far enough away, the altitude angle would be higher in the west after noon, and in the east before noon. You have more of the math for this than I do, I suspect.

Exactly how far away are the Sun and stars in Tolkien’s cosmology? That would be really useful to know, especially if you’re trying to use them to navigate, but we don’t know the answer: Tolkien’s pre-Downfall worldbuilding didn’t get that far. (Check out Kristine Larsen’s work on the astronomy of Middle-earth for what we do know.)

My take on this is that the existence of the Gates of Morning, and the fact that they were visible from Númenórean ships, suggests that the Sun is close enough to Arda for parallax to be a thing (to say nothing of Morgoth’s assault on the Moon, or the Eärendil-Ancalagon matchup: Ilmen does not appear to be impossibly far off). On that basis I assumed a smaller celestial sphere, where celestial objects would have parallax effects, when working this piece up.

Things would have been a lot easier if the Sun and stars were far enough away, per Ian @14. Instead, I think we’re dealing with a world where simple but essential concepts like noon and north are exponentially more difficult to determine than they are in our world, especially if (like me) you really don’t have the math for this.

Of course, as AlanBrown @6 points out, flat earths are inherently ridiculous, so there’s something absurd about trying to make something as rigorously mathematical as navigation work in such a world. But it’s fun to try.

Someone on reddit noted the maps needn’t be complete either, so there could be islands. Though islands would suggest islanders, complicating the rather simplistic demographics of Middle-Earth. (Perhaps any island dominated by Royalist Numenoreans also got eliminated?)

Tolkien’s worldbuilding was detailed in many ways but far from complete. Late in life he wanted to dump the “flat world” as a Mannish myth, but never got around to revising, well, everything. He was never happy with an origin for orcs (Chris picked the “corrupted elves” version for the Silmarillion; “corrupted men” doesn’t work with the timeline there.) The Numenoreans had absolute primogeniture for most of their history, yet the king list is mostly kings; I suspect the list came first, the idea of absolute primogeniture came later, and he never went back to give a more biologically plausible list of royal first children. The essay on osanwe-kenta describes it as unlimited range telepathy between intimates, and I don’t think anyway else written suggests it exists — maybe Galadriel knowing she can go West now, or Gandalf getting permission to bring hobbits to Valinor, but the Silmarillion doesn’t suggest Noldorin princes having mental cell phones with each other. And then there’s what elves and orcs and dwarves ate before the first sunrise…

Finding this kind of quality Tolkien analysis on a week without the Silmarillion Primer was a pleasant surprise. It does remind me of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld (which runs on laws of narrative and revels in the absurdity of its premise) where his answer to the many questions arising from the shape of the world is “Arrangements are made”.

I just wanted to say that I appreciated the Monty Python reference – strange spirits lying in seas is no basis for a system of navigation. It made me laugh.

Would something like a Viking Sunstone help? They are thought to have polarized light, offering an optical bearing even on cloudy days. An ability to see the polarization of light is also used for navigation by some animals.

Atmospheric refraction will have a large effect on a flat world. Though its effects can be variable.

Jonathan Crowe (16): The difficulty of defining ‘north’ exists also if your universe (game world?) is a hyperbolic plane. You could mark a pair of axes, and define the cardinal directions as to or from the nearest point on an axis; these become less orthogonal as you get farther from the axes. Or you can choose any number of points on the circle at infinity as ‘poles’.

@6: I believe it’s a popular misconception that Columbus’ skeptics believed the world was flat. Rather, he and they differed on the estimated diameter. He was wrong, in fact; he thought the Earth was smaller than it is, which led him to believe China was closer to Spain. Fortunately for him, North America lay about where he miscalculated China’s position.

I must say interesting analysis. Though trying to rationalize the more mythical ‘flat world’ version could be ultimately futile I think that there may be solution to the posed question of this fragment: ‘ he saw it sink shimmering into the sea, and last of all the peak of the Meneltarma as a dark finger against the sunset.‘ First of all it need not be assumed that in the flat version of the world it is entirely flat like a table, in fact there might be some curvature, more elyptic shape.

Or something like this:

In any case :), I always wondered about navigation in Arda, and this one passage here from HoME 12 is the only reference that acknowledges the navigation’s existence :) hehe:

“‘This was a Sindarized form of Telerin Telperimpar (Quenya Tyelpinquar). It was a frequent name among the Teleri, who in addition to navigation and ship-building were also renowned as silver-smiths.'” And that’s it basically only reference to navigation that I could find ;). So the Sea Elves were masters of navigation but specifics are unknown hehe.

As for the islands, indeed there are some ‘western isles’ the remnants of Beleriand: Tol Fuin, Tol Morwen, Himling, possibly Isle of Balar survived throughout the Second Age, so those islands could be possible stops during voyage to northern shores, to Lindon etc., possibly other unnamed isles could have remained of the sunken Beleriand, further south there could be isles that were simply not mentioned (Tolfalas is too close to shores in Bay of Belfalas, but there could be other islands out there, near Numenor itself was also small island Tol Uinen, unfortunately as all detailed charts and maps of Numenoreans and their Guild of Venturers were lost during Downfall we can’t be sure), mind you Tolkien doesn’t explore the sea maps (in fact it is remarkable that with all the love for the sea, we don’t get adventures and sea voyage stories, they are only hinted at in Aldarion’s case and in the exciting adventures of Voronwe who was sailing for seven years to reach Aman, even journeys of Earendil are not recorded, I always found that the sea and it’s haunting beauty always was in the background of Tolkien stories and I would desperately want to learn more :) some full narrative of adventures on high seas hehe). As for ships and their designs, well while oars are often used to supplement the propulsion it may be that the designs were also more ‘advanced’ towards the ‘sailing ships’ of what we would perceive to be more suited to open seas (it may be my false impression but I always thought that traditional galleys are less suited to open high sea journeys, are more useful near the shorelands, more peaceful seas like the Mediterranean). There is this little passage:

“And thence at times the Firstborn still would come sailing to Numenor in oarless boats, as white birds flying from the sunset. And they brought to Numenor many gifts: birds of song, and fragrant flowers, and herbs of great virtue.” ‘Oarless’ could mean a full on sailing ships. Still the oars could be used as support when there would be no wind or something :). In other texts within HoME their is this also:

“Therefore he began to prepare a vast armament for the assault upon Valinor, that should surpass the one with which he had come to Umbar even as a great galleon of Numenor surpassed a fisherman’s boat.

The Peoples of Middle-Earth, HoME Vol 12, Part 1, Ch 5, The History of the Akallabêth

So there could be quite a variety of ship designs.As for mathematics well definitely people of Middle-earth must have studied it, possibly there were other branches of science like physics etc (Saruman somehow knew that white light can be broken into different colors :) so optics, maybe Feanor’s crystals in which images could be seen were also in part optical devices in addition to the palantiri :) of course the Elves already have supersight). It is clear that math was needed for setting up the calendars (also engineering would require some), there is basic algebra, also the elven numbers system was apparently duodecimal, there is Cuivienyarma legend that is basically a “child’s tale mingled with counting lore” from what I recall there are apparently symbols of numbers in elvish (as in mathematical symbols for numbers though I’m not certain, the source might have been Parma Eldaramberon which seems to contain some of Tolkien’s writings not seen elsewhere).

A curved flat earth would be the most bonkers idea ever, there needs to be at least one crank somewhere pushing it! It would take care of the problem of ships disappearing over the horizon hull first, at the expense of introducing a gravity that varies in direction depending on where you stand, one of the primary intuitive objections flat-earthers seem to have, if I’m not mischaracterising them.

Another problem with a curved flat earth (I’m talking today rather than your clever workaround for Second Age Arda) is that early surveyors were able to use the curvature to determine the radius of the Earth. al-Biruni did this is the eleventh century using a mountain. If you do the experiment, find the curvature, and still say the earth has an edge, then you’re just imagining the earth as being a cap the size of a small piece of the earth we know. This only works until someone finds the New World in the fifteenth century.

Had a thought while revisiting this topic: While sailing on a flat sea they should be able to see further than on our curved Earth. Combine it with possibly keener eyesight. which seems like a very Tolkien thing to give the Numenoreans, and they should be able to see their island from far away while sailing back from Middle Earth.

I was going to say, you can always headcanon that the “flat earth” was a myth of the contemporary Middle Earth, much like in the real world there is a mythology that the earth was once flat, or that people believed it was flat at some points in history.

Apparently Tolkien himself thought about it as mentioned above.

Off topic, but the estimates of the distance between Númenor and Middle Earth are very wrong.

Fonstad’s maps are not canonical or even accurate on Global issues, there are many reasons to this, one of them is that the Ambarkanta is a early draft of Tolkien mythology, of a World where there were only Beleriand, Valinor and Utumno, very difficult to consider it as a accurate sources for the size of Middle Earth and the World in general.

The most accurate basis on the Arda’s dimensions are in Akalabeth:

-> Númenor is nearer to Valinor than Middle Earth

-> Ar-Pharazôn armada took 39 days to reach the Shores of Aman, that’s at least 3,000 miles in straight line, and much more by sea routes

-> The Belegaer was far wider in the middle than in the north and in the south

-> The Belegaer was expanded and deepened after the Fall of Illuin and widened again in the War of Powers.

Said that, the distance between Romenna and Lindon, Lond Daer or Umbar is not less than the distance between Andúnie and Aman, they are at least slightly larger.

My estimates is that the Great Sea had at its widest point 12,000 km, assuming that Númenor was in the Girdle of Arda, that’s 5,000 km from West reaching the shores of Aman and 7,000 km East reaching Middle Earth. This was the distance that Fëanor would travel from Alqualondë to the east where the sea was said to be ”immeasurable”.

Fonstad’s calculations are derisory, in the Atlas Númenor is only 800 miles (1,300 km) east of Valinor, that’s 4x less than the most conservative estimates of the Ar-Pharazôn journey. According to the Atlas, Ar-Pharazôn traveled at a speed of 1.3 km per hour for 39 days, this is ridiculous.

The Voyages between Middle Earth and Númenor are said to have lasted ”many days”, even Elendil’s flight under extraordinary conditions of the wind ”wilder than any that Men had known” took many days to reach the shores of Endor, vague descriptions but informative enough to have an idea of the dimensions of the world..

It is not just the sea, Middle Earth also is greatly reduced in the Atlas, especially the Lands of east.

In the map, the Orocarni are only 900 miles from the sea of Rhûn, the argument (proven false by Peoples of Middle Earth), is that the Sea of Rhûn was a remnant of the Sea of Helcar. It practically ignores the descriptions of the Eldar’s march where it took many years to reach the Anduin. Even under conditions of nomadism, stops, and lack of paths, the Wanderings of Quendi covered a far greater distance than is shown on the map, more important, there were still lands east of Cuiviénen. In the Third Age the Dwarves of East Houses took 3 years to reunite with their brethren in the Misty Mountains, it would be like a trip from China to Ireland.

The Atlas of Middle Earth is the main reason why Tolkien fans complain that Arda is small, many people still keeps the book as canonical. Arda is 10,000 km West to East in the Atlas. Tolkien said clearly that Arda is our World, the dimensions of Valinor, Middle Earth and the East Lands were never given, we just know they are immense, the Atlas only reduced them to a level that did not correspond with the post-1940 Legendarium.