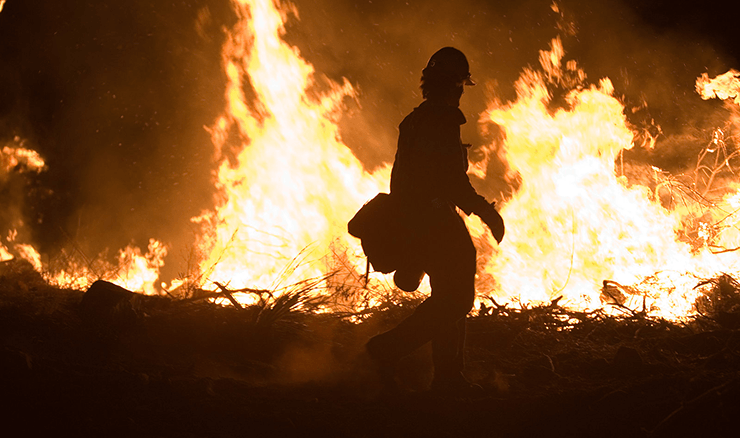

Right now, the largest and most deadly wildfire in California history is burning. Last year, Hurricane Harvey drowned southeast Texas under punishing, endless rain; a month ago, Hurricane Florence did the same to North Carolina. Apocalyptic-scale disasters happen every day (and more often now, as climate change intensifies weather patterns all over the world.) Apocalyptic disaster isn’t always the weather, either: it’s human-made, by war or by industrial accident; by system failure or simple individual error. Or it’s biological: the flu of 1918, the Ebola outbreaks in 2014.

In science fiction, apocalypse and what comes after is an enduring theme. Whether it’s pandemic (like in Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven and Stephen King’s The Stand), nuclear (such as Theodore Sturgeon’s short story “Thunder and Roses” or the 1984 BBC drama Threads), or environmental (Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140, and a slew of brilliant short fiction, including Tobias Buckell’s “A World to Die For” (Clarkesworld 2018) and Nnedi Okorafor’s “Spider the Artist” (Lightspeed 2011), disaster, apocalypse, and destruction fascinate the genre. If science fiction is, as sometimes described, a literature of ideas, then apocalyptic science fiction is the literature of how ideas go wrong—an exploration of all of our bad possible futures, and what might happen after.

Most of apocalyptic literature focuses on all the terrible ways that society goes wrong after a society-disrupting disaster, though. This is especially prevalent in television and film—think of The Walking Dead or 28 Days Later where, while the zombies might be the initial threat, most of the horrible violence is done by surviving humans to one another. This kind of focus on antisocial behavior—in fact, the belief that after a disaster humans will revert to some sort of ‘base state of nature’—reflects very common myths that exist throughout Western culture. We think that disaster situations cause panic, looting, assaults, the breakdown of social structures—and we make policy decisions based on that belief, assuming that crime rises during a crisis and that anti-crime enforcement is needed along with humanitarian aid.

But absolutely none of this is true.

The myth that panic, looting, and antisocial behavior increases during the apocalypse (or apocalyptic-like scenarios) is in fact a myth—and has been solidly disproved by multiple scientific studies. The National Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program, a research group within the United States Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA), has produced research that shows over and over again that “disaster victims are assisted first by others in the immediate vicinity and surrounding area and only later by official public safety personnel […] The spontaneous provision of assistance is facilitated by the fact that when crises occur, they take place in the context of ongoing community life and daily routines—that is, they affect not isolated individuals but rather people who are embedded in networks of social relationships.” (Facing Hazards and Disasters: Understanding Human Dimensions, National Academy of Sciences, 2006). Humans do not, under the pressure of an emergency, socially collapse. Rather, they seem to display higher levels of social cohesion, despite what media or government agents might expect…or portray on TV. Humans, after the apocalypse, band together in collectives to help one another—and they do this spontaneously. Disaster response workers call it ‘spontaneous prosocial helping behavior’, and it saves lives.

Spontaneous mobilization to help during and immediately after an apocalyptic shock has a lot of forms. Sometimes it’s community-sourced rescue missions, like the volunteer boat rescue group who call themselves the Cajun Navy. During Hurricane Harvey, the Cajun Navy—plus a lot of volunteer dispatchers, some thousands of miles away from the hurricane—used the walkie-talkie app Zello to crowdsource locations of people trapped by rising water and send rescuers to them. Sometimes it is the volunteering of special skills. In the aftermath of the 2017 Mexico City earthquake, Mexican seismologists—who just happened to be in town for a major conference on the last disastrous Mexico City earthquake!—spent the next two weeks volunteering to inspect buildings for structural damage. And sometimes it is community-originated aid—a recent New Yorker article about last summer’s prairie fires in Oklahoma focuses on the huge amount of post-disaster help which flowed in from all around the affected areas, often from people who had very little to spare themselves. In that article, the journalist Ian Frazier writes of the Oklahomans:

“Trucks from Iowa and Michigan arrived with donated fenceposts, corner posts, and wire. Volunteer crews slept in the Ashland High School gymnasium and worked ten-hour days on fence lines. Kids from a college in Oregon spent their spring break pitching in. Cajun chefs from Louisiana arrived with food and mobile kitchens and served free meals. Another cook brought his own chuck wagon. Local residents’ old friends, retired folks with extra time, came in motor homes and lived in them while helping to rebuild. Donors sent so much bottled water it would have been enough to put out the fire all by itself, people said. A young man from Ohio raised four thousand dollars in cash and drove out and gave it to the Ashland Volunteer Fire Department, according to the Clark County Gazette. The young man said that God had told him to; the fireman who accepted the donation said that four thousand was exactly what it was going to cost to repair the transmission of a truck that had failed in the fire, and both he and the young man cried.”

These behaviors match the roles and responsibilities that members of a society display before the apocalyptic disaster. Ex-military volunteers reassemble in groups resembling military organizations; women in more patriarchal societies gravitate towards logistics and medical jobs while men end up taking more physical risks; firefighters travel to fight fires far away from their homes. The chef José Andrés served more than three million meals over three months after Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico. Humans all over the world display this behavior after disasters. They display it consistently, no matter what kind of disaster is happening or what culture they come from.

What really happens after an apocalypse? Society works better than it ever had, for a brief time.

The writer Rebecca Solnit wrote an entire book about this phenomenon, and she called it A Paradise Built in Hell. She points out that it is really the fear on the part of powerful people that powerless people will react to trauma with irrational violence that is preventing us from seeing how apocalypse really shapes our societies. Solnit calls this ‘elite panic’, and contrasts it with the idea of ‘civic temper’—the utopian potential of meaningful community.

Apocalyptic science fiction tells us so much about how the future is going to hurt—or could. But it can also explore how the future will be full of spontaneous helping; societies that bloom for a night, a few weeks, a month, to repair what has been broken. The human capacity to give aid and succor seems to be universal, and triggered quite specifically by the disruption and horror of disaster. Science fiction might let us see that utopian potential more clearly, and imagine how we might help each other in ways we never knew we were capable of.

Arkady Martine writes speculative fiction when she isn’t writing Byzantine history. She is overly fond of borders, rhetoric, and liminal spaces. Her novel A Memory Called Empire publishes March 26th with Tor Books. Find her on Twitter as @ArkadyMartine.

Arkady Martine writes speculative fiction when she isn’t writing Byzantine history. She is overly fond of borders, rhetoric, and liminal spaces. Her novel A Memory Called Empire publishes March 26th with Tor Books. Find her on Twitter as @ArkadyMartine.

There are exceptions but by and large people behave much better than even they would have expected in a real emergency or disaster. One of the surest way to get panic and screaming in the aisles is lack of communication. People can deal with even the worst news better than they can with uncertainty. Radio silence is asking for trouble. People seem to spontaneously organize themselves around leaders, often the last person expected, who step up to deal and have obviously sensible ideas on how. Being told what to do is immediately calming and reassuring and starts people thinking again and showing initiative themselves.

The problem is the real world disasters you are discussing in comparison to the literature disasters are localized. No data exists in research that shows how the human population would react to an 80-90% population loss. During these incidents, you are citing people who were not affected coming to help along with some that were actually present at the time.

As someone who has been close to disasters like Floyd, Hugo, and Michael, I agree that most of us will act with kindness and sense rather than brutality. We will help others, rescue pets, and share resources. However, in areas with high population density like large cities, the predators already there like gangs will take advantage which can incite mobs. In NYC, for example, predators have roamed during power outages and civil unrest, yet decent people pulled together during 9 11. People are people, and most of us are decent human beings, and a few aren’t.

I’ve never quite understood how, in most zombie apocalypses, the military utterly fails to fight off the hordes. I can see it in 28 Days Later, since the people turn very quickly and them zombies/infected run darn fast (and contact with blood is all that is needed to spread), but in The Walking Dead, it can take some time to turn (they seem kind of inconsistent with it). While most soldiers are trained to shoot center of body mass, high rates of fire will account for plenty of headshots, not to mention the devastating effect high powered weaponry has on fleshy bodies. And bombs/missiles/grenades may not necessarily destroy the brain, but they can very effectively render a zombie far less effective. Blowing off limbs, shattering bones, flying fragmentation work well to reduce the chances of spreading the infection. Zombies clump together, so explosives can very effectively take out huge chunks of a horde.

@2, 3 make very good points. I’d add that history has plenty of examples of massive disasters. The Black Death epidemic comes to mind.

My mom likes to say the greatest lesson of history is that no one learns the lessons of history.

@2, @3: The dark flip side of the urge to join with and help one’s community is the corresponding tendency to define out-groups. As the latter breeds conflict, it makes sense that it tends to be over represented in fiction. Urban settings are useful since the presence of many more people provides so much more opportunity to define Us and potentially multiple Thems (even before the genuine miscreants show up to take advantage).

That’s why Independence Day is such a guilty pleasure for me. The film is full of instances of people coming together to help each other.

I think it would more likely turnout similar to current trouble spots were resources are low and needs are high or the expansion of USA into Spanish Empire America and Native America. You’d have normal normal enclaves trying to survive among the tribal warlords or Barons until they grew large enough to overcome the attacks.

Having been in a handful of disasters, I concur that people largely come together and help each other out. The instances of bad behavior tend to get highlighted because we *expect* them to occur, primed by countless apocalyptic tales. Those perpetrators would likely commit similar acts at another time anyway.

That said — the better you know your neighbors, the more likely those webs of assistance can work.

@@.-@ My biggest beef is with the continued “survival” of zombies. A good chunk of nature–flies, birds, bugs, microganisms– is around to get rid of dead stuff. Then there’s the sun and heat which speeds up the ripening process. Zombie bodies would be disintegrating in a matter of days. All most of us would have to do is hunker down for a few months. Maybe some snipers on roofs, after that, to take down new zombies. In a few years, most of it would be over.

@10 this reminds me of the Voorpret species in Catherynne Valente’s _Space Opera_

To amplify on #2’s point, in a local disaster everybody understands that, before too long, a very large number of people with vast resources are going to be coming from the undevastated outside world to restore something approximating the status quo ante. Some people are going to die, or suffer great losses that won’t be restored. And maybe some people will score a free big-screen TV from the local Wal-Mart and get to keep it. But nobody is going to be able to set themselves up as the Supreme Warlord of the post-apocalyptic order and make it stick, and nobody has to worry about starving to death because they didn’t sign on with the right warlord early enough. Mostly, people can look forward to living long lives pretty much like they would have if there had been no disaster, except with the memories of what they did and what their neighbors did during the disaster.

I’m glad that this usually results in everybody pulling together to help everyone pull through with minimum losses. But it doesn’t tell us much about what happens after the apocalypse, because apocalypses are fundamentally different. And, Buffy Summers notwithstanding, they usually aren’t plural, so we don’t have a statistically significant data set to work from.

@10, yeah, they don’t really discuss that on TWD as far as I recall. I haven’t read the comic, so I dunno how it was handled there. Presumably in TWD, since anyone that dies automatically becomes a walker if the brain isn’t destroyed, there could be a replenishing source, but even then, over time, it would slack off. The 6th episode this season did show some fresh walkers.

I recall one theory being bacteria isn’t chowing down on the zombie flesh all that well, delaying/prolonging the decomp process.

WWZ (and the semi-accompanying Zombie Survival Guide (the most important book you’ll ever read, that book will save your life)) do factor weather and decomposition into the story.

What came to my mind, and to many of the folks responding here is the matter of scale, disaster versus catastrophe. When the Red Cross / FEMA / National Guard / CDC / Doctors without Borders are all knocked down too, when there’s no cavalry coming over the hill, EVER, well… Survivors will adapt to the new conditions as best they can and society will reinvent itself..Societies really, likely localized, not uniform by any means. And they’ll lump along until the next catastrophe hits, and the next and the next. Climate is a spinning coin on the coffee table, beautiful and temporary. To us tiny motes with mayfly lives it seemed forever, but it never was. So what we do is knock over that coin, slap pur collective hand down on it and flatten it. So clueless, so clueless!On the bright side, the rich will only last a couple more generations than the rest of us. Long enough to really be forced to grapple with how badly they fukt up.

S.M. Stirling postulates that in the event of the actual end of the world as we know it, i.e. a literally planetwide breakdown, people who were already in the habit of not expecting the social contract to work in their favor would be the majority of the survivors: “When the going gets weird, the weird get going.” So he builds the future society of his Emberverse (in which something not immediately explained makes high-energy technology unworkable within the usual human travel zone on Earth) from criminal gangs, intelligent sociopaths, disillusioned ex-military, and assorted peaceful spiritual/subcultural groups that are mainstream now but weren’t in 1998. They have drastic effects on the people they save along with themselves; as one character describes it, she (a witch, folk musician, and reenactor) used to be in the counterculture, finding whatever space she could for the life she really wanted to live, but after TEOTWAWKI there’s nothing pushing against the other side of the door.

@2

In fact, one set of societies has experienced a drastic sudden population loss over a short period of time, with no possibility of outside hep – the indigenous societies of the New World underwent catastrophic popul;ation collapses after European contact. I don’t recall any descent into savagery on their past, although admittedly in a lot of cases record-keeping was not very good.

Look up the 1923 Japan earthquake aftermath.

The whole point of David Brin’s “Postman” (not the film!) is that the title character is a source of hope. He brings the impression that the disaster is being sorted out and you only have to hold on a little longer. That hope is what turns things around and keeps people helping each other.

Another point in the book is that the bad guys are the survivalists – the ones that are only in it for themselves.

@@.-@, yeah, in any zombie scenario, as long as there is not a rapid social breakdown in the initial shock, when the army responds, they would just clear out the zombies from one area at a time. A tank even without ammunition could just run over 100:s of zombies in a day. The ONLY realistic zombie apocalypse scenario is Cell, because it would hit everywhere at once and particularly among the people expected to deal with the threat because they would be the first to get mobile calls. And by the time people understand the nature of the threat and gets organized, the “zombies” have become intelligent too.

I’ve always had the impression that there are two distinct grades of disaster behaviour: Most people will stick together and help each other unless it gets so bad that their individual survival is threatened. In that case, they will stop caring about others and try to save themselves.

In other words, people care about each other, but they care about themselves just a little bit more. There are exceptions – people who are only interested in themselves, people who sacrifice themselves for others. But the average human being will help as long as their own survival isn’t at stake. I think that makes us a fairly nice species.

This is an excellent point – it’s as though people are waiting for something to go wrong to give them permission to act like decent human beings.

And you can see it at every scale, even with very very minor disasters like (to take the most recent example I saw) an old woman falling over on the street – suddenly the crowd of blank-eyed shoppers around her turns into a swarm of people offering to help and the poor woman, who’s probably got nothing worse than a bruise and a bit of a shock, disappears under a sort of well-meaning rugby scrum.

But I’d make one huge exception – when the disaster is a violent one from the beginning, a civil war or something. One of the most striking things about (again, just taking an example I’m familiar with) the war in Bosnia was the speed with which the country went from zero to atrocity. They didn’t ramp up to it slowly like the Germans did; the worst stuff happened in the first six to twelve months of the war. It’s as though everyone had a sealed envelope that they opened on a given signal that told them how to be Nazis, and they got right on with it. Same in Rwanda with its hundred thousand genocidaires. If you want to write about post-disaster chaos and brutality, that’s where you should look.

That’s why Independence Day is such a guilty pleasure for me. The film is full of instances of people coming together to help each other.

As I may have ranted before: this is why monster movies (like Independence Day) are inherently left-wing. Because they start with a disparate group of people who have no real reason to like or trust each other, but who are forced by circumstances to work together for the common good, and who all have something to contribute. Tremors is the classic example. Val and Earl are the heroes, sure, but they need Rhonda the geologist to tell them what they’re up against and how to detect it. And they need Burt Gummer as well because he knows how to make pipe bombs. And Burt needs Miguel because Miguel comes up with the idea of using Walter’s tractor as a distraction. The classic line from any monster movie is “Listen! If we work together we can beat this thing!” There you are. Big Society liberalism in cinematic form. The white president needs the black fighter pilot and the black fighter pilot needs the Jewish computer guy and they all need the lunatic crop duster.

In fact, a foreigner could do worse than simply assuming, based on Independence Day, that the four main characters represent the US population in exact proportion: 25% black people, 25% other minorities, 25% sane white people and 25% deranged white people.

MByerly writes: “[I]n areas with high population density like large cities, the predators already there like gangs will take advantage which can incite mobs.”

There is actually no strong evidence for this generalization, and quite a bit of evidence that, in modern America at least, the crime rate in densely-populated urban areas is lower, or at least not higher, than in the country overall.

http://science.time.com/2013/07/23/in-town-versus-country-it-turns-out-that-cities-are-the-safest-places-to-live/

I’ve lived in New York City for 34 years. I’ve never seen a “predator” or a “gang” “incite a mob.” The idea that cities are typically thronged with “mobs” just waiting to be “incited” is a fantasy.

There are predatory people in the world, but it turns out that rural and suburban populations contain just as many of them as dense cities do.

@21 Your examples of “violent” disasters, are not exactly natural disasters. They are wars. They are not cases of a disaster causing people to form into antagonistic groups. Instead, the antagonistic groups are the cause of the disaster in the first place.

A natural disaster could cause a war or looting if someone took advantage of the confusion to attack a pre-existing enemy, but it would not create the antagonism. This would be an example, and perhaps helped popularise this trope: New York City blackout of 1977. Note that other blackouts have been perfectly peaceful.

I remember during the 2003 blackout, people almost immediately wandered out of their dark houses to brutally direct traffic. It was like one percent of the population had been concealing a secret desire to stand in intersections telling cars when they could go.

Back around 1990 I read a report (courtesty Emergency Preparedness Canada) that an SF grocery chain had looked at how to react to a major disaster and concluded that simply giving away supplies during the emergency had significant long term gains. People remember being gouged in a disaster and they remember being helped.

Back during the ice storm of 1997, I was trying to scrounge supplies for my aunt in Montreal when I realized the product I was looking at in Canadian Tire in Kitchener Ontario had a Montreal phone number. One call later, they put together a case of supplies for her and ran over to her, with the understanding I’d mail them a check for it.

May I recommend the practical advice on survival after collapse provided by Dmitry Orlov? Orlov bases his writing on russia post Soviet Union.

The one piece of advice I want you all to take to heart is: you can’t just save yourself and your family – you must include your neighbours in any solution, effort or sharing of resources.

See:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Five-Stages-Collapse-Survivors-Toolkit/dp/0865717362

@21 – in the case of the Balkans conflicts, we’re talking about a geography that has been contested for a long time in internecine tribal conflict. And some ethnic groups had indeed dabbled in fascism earlier in the 20th century. Basically the country was being held together by Tito’s socialism and the whole project came undone quite quickly when he died without an obvious successor. I think a lot of politicians attempted to build power bases by cultivating ethnicity-based systems of patronage, which accelerated the turn towards ‘difference’. It wasn’t long ago that Serbo-croat was considered a single language.

I think that this is the main stumbling point of this ‘people try to help each other’ idea. While I broadly think it’s true, there are instances where previously-cultivated senses of ‘otherness’, paranoia about the kind of collapse of society that is described here, and power relationships, combine to cause atrocities – generally by people who hold power but have been induced to consider themselves victims. An example of this is the murder of black people by white ‘vigilantes’ (let’s be blunt – racists organising themselves into gangs the moment they thought circumstances gave them permission to do so). In particular I think there were incidents where black people were shot as they attempted to reach an evacuation point that required them to pass through a ‘white’ district.

So if anything, I’d suggest that this paranoia about social breakdown is a fear of the current order breaking down (with attendant privileges being lost) and a desire to enforce that which is secretly known to be unjust, and a crude mapping of usually racist prejudices onto a chaotic situation – see an earlier commenters comments about ‘predators’ and ‘urban gangs inciting mobs’.

I should have mentioned that my second point was referring to New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina.

@@.-@ The reason “zombie” stories are shaped the way they are, and are fascinating, is because initially it’s impossible to see the threat. The army would mow people down because they’re sick? Of course not! They’re people! By the time they realize that they aren’t people and they aren’t merely “sick” the army itself has lost cohesion. Individuals can and do kill many zombies – that’s exactly what you see in the “action” part of the stories – but they are usually overwhelmed by sheer numbers, because the zombies don’t feel pain or fear, do not think, and are attracted to the noise of the weaponry. And there are a lot of them.

It turns out (at least in fiction) it’s a better survival strategy to /not/ try to eliminate the zombies, to just avoid them instead. Really, once some form of organized society is established a routine of elimination by various means would be beneficial for long-term stability – but most of the stories don’t even come close to that point, so there isn’t much exploration of that. Regardless, that would be loooong after the point that you’re addressing.

In particular I think there were incidents where black people were shot as they attempted to reach an evacuation point that required them to pass through a ‘white’ district.

There was certainly one – but the killers in that particular case were not white vigilantes but law-enforcement, the Danziger Bridge murders. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Danziger_Bridge_shootings There may well have been others as well.

in the case of the Balkans conflicts, we’re talking about a geography that has been contested for a long time in internecine tribal conflict.

This was a common belief in the West during the war – that “these people” were just fighting due to ancient inexplicable tribal hatreds and what can you do? Not entirely accurate. Bosnia before the war was a highly integrated multi-cultural society. Intermarriage rates between the different groups were higher than would be expected from random assortment.

There’s a gross assumption here that there is equal weight to the reaction to a short-term natural disaster, or varying proportions, but generally local, and to the total and progressive full-scale apocalyptic breakdown of social structures and law and order.

In the former there is always the larger support network – familial, communal and government, that will be able to respond and that issues will be somehow rectified, or at least minimised.

Not so with the apocalypse. Society is a thin veneer over the natural baser instincts of survival. When the need for resources outstrip the available supplies, and there is the general acceptance that no help is coming, then the situations we see in fictional events will be closer to the truth than not.

@2 There is real-life experience europeanEculture/history and frankly speaking most of post-apocalypse writers are basing their stories if it. 1) giant death toll – Europe after Black Death plague in 1350s which claimed almost 60% of population. Once death toll stopped climbing and worst subsided, raging mobs looted and destroyed empty houses of rich, killing some remainders, bodies lay strewn around streets and in houses, people attacked “others” like Jews, dark-skinned people, foreigners. The desire to control the peasants led to serfdom in eastern Europe that lasted for another 400 years.

2) Collapse of Civilization – fall of Roman Empire= Black ages. Many cities were sacked and abandoned, forests reclaimed farmlands, people huddled in close – knit tiny villages, constantly attacked by raiders, and terrified, diseases returned.

After the fall, after the plague, some psychopathic greedy bastards did trash and steal (stealing should of course be distinguished from recycling stuff from abandoned buildings, of course), because some people cannot wait to cast off the normal duties of society and indulge their baser instincts; but then everybody else starts forming new societies and new communities in order to protect each other against the nutters and bastards and start forming alliances and forging new trade links, and build things again; and then they eventually hunt those indulgers of those baser instincts down and string them up from the nearest tree. As is right and proper. People are stronger when they speak in unison.

pnh @24 – To be completely fair, that study indicates that the incidence of murder is higher in cities. It’s balanced out by the incidence of accidents (especially car accidents) in the country.

However the key is in the detail that the enormous majority of victims of firearm homicide in the city are men 20-44. As a rule, gang members kill each other, not others. The assumption in calling them “predators” is that, given a social breakdown, they’ll start killing others too. But why would they? Evidence in e.g. Katrina’s aftermath suggests they wouldn’t.

There’s a difference between fast calamities, in which most people either pitch in or sit around in shock, and slow grinding declines that take generations to play out, in which more is actually lost and more people sink to ugly selfishness. A point John Michael Greer repeatedly made, which seems correct from my reading of history and information from colleagues in a country currently in bad shape, is that banditry becomes a severe problem first in rural areas. Urban people will steal when desperate and gangs will rob and bash individuals here and there, but in any city with functioning law enforcement or military garrisons, a bandit gang of the sort that made a living slaughtering farm families in remote areas would be stomped on hard and fast.

I’m just now reading M. K. Wren’s A Gift Upon the Shore, in which, at a time of economic and ecological collapse but before the final nuclear holocaust, the protagonist witnesses packs of murderous bandits going house-to-house in rural Oregon. I’m sorry to say I can think of groups in America today who could easily turn into this. All you need is a bunch of well armed, disgruntled young men who don’t much value the lives of people outside their ingroup.

Western culture? Fear of breakdowns of law and order seems to be greater in Asian cultures, particularly China.

Some folk really do seem invested in the idea that we’re all going to tear each other apart like ravening spiders the minute the lights go out, don’t they? Thank you for this article. I wrote about similar stats in an article I did for my blog on the misogynistic nature of apocalyptic fiction and apocalyptic myths. If you want to take a look at similar examples and stats, read the stuff under the heading “Myth 1.”

The one exception to “people cooperate in disasters” is famine. Historical studies of extended famines tell us that people will prey on those they perceive as weaker than themselves for meat. Soldiers in extended sieges will murder their wives. Parents will eat their own children. I covered that in the post too.

This doesn’t happen as long as survivors have any hope at all of relief. Thin relief efforts and the hope that at some time, this will end, are enough to stave it off.

Thank you for doing good work in trying to counter these myths! I will link this and try to give it some more bandwidth.

I know I might sound cynical here, but I seriously think if anything apocalyptic should happen, we survivors would tear each other apart. Even if there is no zombies involved. I mean, these days violence is practically all you see on the news. Think about the ‘Black Fridays ‘ and how people, without hesitation, will literally shed blood just to get a good deal on presents. Now apply that method to food, water, medicine, etc… What do you think will happen? Rioting, screaming, fighting and ultimately blood in the streets. Along with a lot dead and maimed people.

I like the positive message of this article. A friend of mine is a police officer and was assigned to help out in Houston, TX after hurricane Harvey. He told me that the grocery stores hit by looters would be low on/out of booze, candy, soda, chips, etc. but would still have plenty of bread, fruits and vegetables, milk, eggs, etc. He said that’s pretty typical of situations like that.

Bollocks! I wrote a load of stuff and lost it! These things take forever when you’re old … Nevermind, I was simply trying to articulate my gratitude on a positive take on the apocalypse X

@40 I take that with a large degree of salt, based on the myths perpetuated by law enforcement the world over about literally anybody who is not law enforcement. I wouldn’t trust a cop to tell me fire is hot, much less them telling me about how their supposed social inferiors ignore good wholesome food for trashing stuff to get party supplies. Especially a Texas cop.

A lot of false and horrible stories were gleefully reported by the media after Katrina, and i can’t remember them ever being retracted,much less apologized for.

@21: Rwanda was ramped up slowly, but outsiders weren’t paying attention and didn’t care. The Hutu leaders were systematically stoking racial hatred, intensifying existing societal fractures[1], and stockpiling machetes. The dog whistles were loud to those who could hear and the targeted radio broadcasts were hair-raising. What was sudden was the execution.

[1] I was in Rwanda the year before the Genocide. There were few problems perceptible to outsiders and little low-level corruption. For example, soldiers at the traffic stops outside the city never once hit us up for so much as a cigarette. Nonetheless, the Tutsi/Hutu fractures were there.

@ 41, Ldc:

Bollocks! I wrote a load of stuff and lost it! These things take forever when you’re old …

I write stuff on my word processor. When I’ve got it right, I copy and paste.

If Tor eats my entry, I recopy the original and repost.