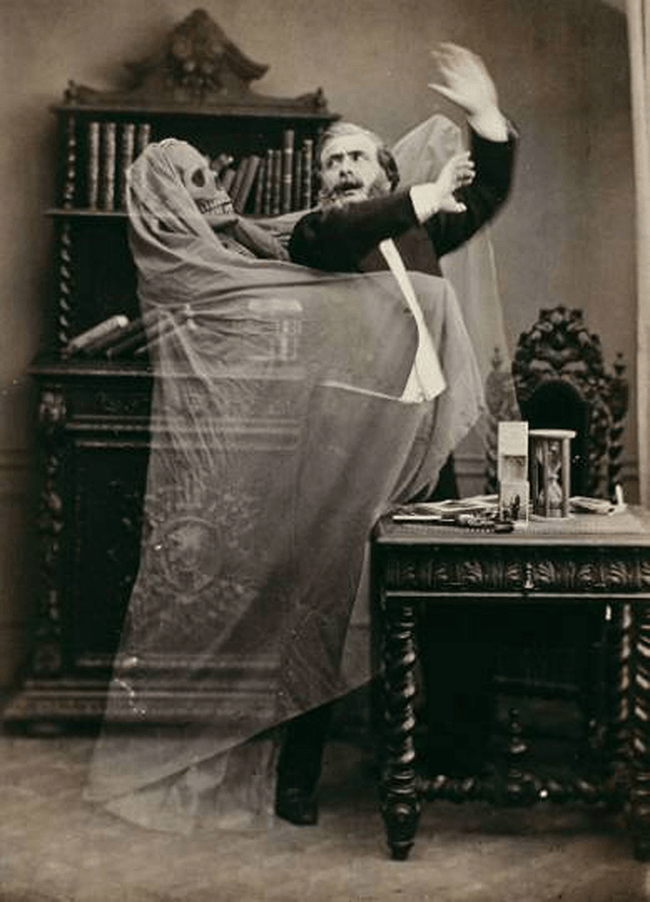

In the wake of Sherlock Holmes’s massive success the world was so overrun by lady detectives, French detectives, Canadian lumberjack detectives, sexy gypsy detectives, priest detectives, and doctor detectives that there was a shortage of things to detect. Why not ghosts?

And thus was spawned the occult detective who detected ghost pigs, ghost monkeys, ghost ponies, ghost dogs, ghost cats and, for some strange reason, mummies. Lots and lots of mummies. Besides sporting ostentatiously grown-up names that sound like they were randomly generated by small boys wearing thick glasses (Dr. Silence, Mr. Perseus, Moris Klaw, Simon Iff, Xavier Wycherly) these occult detectives all had one thing in common: they were completely terrible at detecting.

Arthur Conan Doyle’s consulting detective, Sherlock Holmes, changed everything in mystery fiction when his first story “A Study in Scarlet” appeared in Beeton’s Christmas Annual in 1887, but before him came a whole host of proto-detective stories reaching back to Germany’s true crime family fun classic, A Gallery of Horrible Tales of Murder (1650), the fictionalized criminal biographies published as Newgate novels by writers like Edward “Dark and Stormy Night” Bulwer-Lytton, and Edgar Allan Poe’s Auguste Dupin (“The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” 1841). From out of this literary rabble emerged the very first occult detective: Dr. Martin Hesselius.

Physician, man of letters, and malpractice enthusiast, Dr. Hesselius first appeared in “Green Tea,” published in the October 1869 issue of All the Year Round, then edited by Charles Dickens. He was the creation of Irish writer Sheridan Le Fanu, known as “The Invisible Prince” because he rarely left his house after the 1858 death of his mentally ill wife. Obsessive and neurotic, Le Fanu was haunted all his life by a recurring nightmare in which he stood transfixed before an ancient mansion that threatened to collapse on him; when he was found dead of a heart attack in 1873 his doctor remarked, “At last, the house has fallen,” which, while witty, probably wasn’t the sort of thing his family wanted to hear.

“Green Tea” is the best of Le Fanu’s ghost stories and it immediately established that same callous tone of professional disregard for human emotions that would come to characterize all occult detectives. Recounted by Hesselius’s eight-fingered medical secretary, “Green Tea” finds Reverend Jennings approaching Dr. Hesselius for help with a phantom monkey that’s driving him bananas. Hesselius determines that too much reading while swilling green tea has inadvertently opened the reverend’s third eye. Hesselius commands Jennings to summon him immediately the next time he sees the monkey. The next time the monkey appears Hesselius is on vacation with orders not to be disturbed, so Jennings slashes his own throat. Hesselius responds with a mix of defensiveness and braggadocio. He’s successfully treated 57 cases of opened third eyes, he writes to a colleague, and he could have cured Jennings, but Jennings was a stupid weakling who died of “hereditary suicidal mania” and, technically, he wasn’t even Hesselius’s patient anyways.

Defensive, condescending, full of made-up knowledge, and absolutely lethal to patients — these are the hallmarks of the occult detective, such as Algernon Blackwood’s Dr. John Silence, probably the biggest jerk in weird fiction. Like Batman, Silence vanished for five years of international training, only to return well-versed in being obnoxious and making things up. His first adventure was “A Psychical Invasion” (1908) in which a humorist overdoses on marijuana and loses his sense of humor. Silence uses a magical collie to fight what he claims is an evil ghost lady, relays a bunch of pseudoscience as patronizingly as possible (“As I told you before, the forces of a powerful personality may still persist after death in the line of their original momentum…If you knew anything of magic, you would know that thought is dynamic…etc.”), then he has the humorist’s house torn down.

Occult detectives love tearing down houses, and they hate women, foreigners, and Eastern mysticism, in about that order. In Silence’s “The Nemesis of Fire” an outbreak of spontaneous combustion is caused by a selfish old lady who stole a scarab necklace from a mummy. Silence demonstrates his bedside manner by tossing the spinster to the pissed-off mummy which burns her to death, then Silence sneaks her charred corpse upstairs and tucks it into bed, presumably to be discovered by her maid in the morning.

Silence battled lots of foreigners, including Canadian werewolves (“The Camp of the Dog”), German Satanists (“Secret Worship”), French cat witches (“Ancient Sorceries”), and math (“A Victim of Higher Space”). Every one of his stories ends with an insufferable lecture followed by a smug smirk. His only adventure that doesn’t make you want to hurl the book so hard it travels back through time and smacks Silence in the head is also his funniest, “Ancient Sorceries.” Much of it is taken up with its narrator, a silk merchant, returning to visit his old German boarding school and recalling its catalogue of sadistic deprivations fondly (“…the daily Sauerkraut, the watery chocolate on Sundays, the flavour of the stringy meat served twice a week at Mittagessen; and he smiled to think again of the half-rations that was the punishment for speaking English.”), and it’s these giddy, parodic updrafts that William Hope Hodgson sails like a hang glider with his creation, Carnacki the Ghost Finder.

Carnacki’s cases revolve around men dressed in horse costumes just as often as they wind up being about disembodied demon hands chasing him around the room. Using a totally made-up system of vowel-heavy magic (The Incantation of Raaaee, The Saaamaaa Ritual), Carnacki spends most of his adventures crouched in the middle of his electric pentacle, taking flash photos of weird monsters like a nightmare pig (“The Hog”), a floor that becomes a puckered pair of whistling lips (“The Whistling Room”), and an indoor blood storm (“The House Among the Laurels”). His trademark is kicking his guests out of his house at the end of his stories, shouting, “Out you go! Out you go!”

Buy the Book

The Haunting of Tram Car 015

Sometimes his enemy is the ghost of a jester, sometimes it’s Irish people, and sometimes he splits the difference and it turns out to be a crusty old sea captain hiding in a well and a naked ghost baby. Carnacki finds as many frauds as he does phantasms, he loves stupid scientific inventions (an anti-vibrator, a dream helmet, the electric pentacle), and he also loves John Silence-ian laser light show magic battles. And while he occasionally destroys a room or sinks a ship, he doesn’t have the taste for mayhem that characterizes other occult detectives.

One of the most satisfying of these is Flaxman Low, who combines the xenophobia of John Silence with the bogus science of Carnacki to produce an unbeatable package of super-short stories that cannot be read with a straight face. Written by Kate Prichard and her son, the improbably named Major Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard, the Flaxman Low stories move with the brisk, violent efficiency of a man who doesn’t take any guff. In “The Story of Baelbrow” he’s invited to investigate a manor house whose quaint British spook has turned violent. Low discovers that the ghost has teamed up with a foreign mummy to form a super-evil vampire-ghost-mummy. Carnacki would take its photo. Dr. Silence would give a lecture on ancient vibratory emissions. Flaxman Low shoots it about a hundred times in the face, beats its head into a pulp, and burns it.

You only hire Flaxman Low if you are truly hardcore, because his cure is usually worse than the disease. Haunted by a dead leper from Trinidad? Pull the house down (“The Story of the Spaniards, Hammersmith”). Bedeviled by a ghost cult of Greeks? Punch them in the face and move out (“The Story of Saddler’s Croft”). Plagued by a haunted bladder, a phantom taste, or family suicide? Flaxman Low is there to instantly pin the blame on a bunch of Dianists, dead relatives who meddled with Eastern mysticism, or an African man hiding inside a cabinet and using glowing poisonous mushrooms to kill off the family. Then he explodes your house.

Later would come Sax “Fu Manchu” Rohmer’s crusty old junk shop owner, Moris Klaw, and his Odically Sterilized Pillow; the lady occult detective, Diana Marburg, a palmist whose adventures include “The Dead Hand” in which she tangles with a six-foot-long electric eel imported for murder; the abnormally destructive Aylmer Vance; New Jersey’s French occult detective, Jules de Grandin, given to exclaiming “By the beard of the goldfish!” and “Prepare to meet a fully tailored porker before you are much older!” (it sounds better in French); and the man of action, John Thunstone, whose silver sword-cane finds itself frequently embedded in the breasts of a race of pre-humans who originally inhabited North America. And so, vaguely racist, extremely violent, and totally unscientific, the league of occult detectives marches on, razing houses, slaughtering other races, and generally just being absolutely awful people who couldn’t detect their way out of a haunted bladder.

The Best of the Bunch:

- “Green Tea”—Dr. Hesselius screws it up, but that’s one creepy monkey.

- “Secret Worship”—Dr. Silence barely appears, which is why it’s good.

- “The Whistling Room”—Carnacki versus…a floor!

- “The Gateway of the Monster”—Carnacki versus…a hand!

- “House Among the Laurels”—Carnacki versus…Irish people!

- “The Story of Baelbrow”—Flaxman Low fights a ghost-mummy-vampire.

- “The Story of Yand Manor House”—a dining room haunted by a taste and only Flaxman Low can untaste it!

- “The Dead Hand”—so-so Diana Marburg story that is short, sweet, and has an electric eel.

Originally published in December 2013.

Grady Hendrix is a writer and journalist and one of the founders of the New York Asian Film Festival. A former film critic for the New York Sun, Grady has written for Slate, the Village Voice, Time Out New York, Playboy, and Variety. His hard-rocking, spine-tingling supernatural thriller We Sold Our Souls is available September 18th from Quirk Books, and his very own occult detective series, Tales of the White Street Society, is available as a free audio stories from Pseudopod.

Grady Hendrix is a writer and journalist and one of the founders of the New York Asian Film Festival. A former film critic for the New York Sun, Grady has written for Slate, the Village Voice, Time Out New York, Playboy, and Variety. His hard-rocking, spine-tingling supernatural thriller We Sold Our Souls is available September 18th from Quirk Books, and his very own occult detective series, Tales of the White Street Society, is available as a free audio stories from Pseudopod.

So many new Hollywood movie franchises in the public domain.

… ok, I don’t want to read any of these stories, but reading this article was an absolute delight.

I read a bunch of Carnacki stories a few years ago, and I’m so very disappointed that at no point did someone say, “I would’ve gotten away with it if it weren’t for you meddling kids!”

“and Edgar Allan Poe’s Auguste Dupin (“The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” 1841). From out of this literary rabble emerged the very first occult detective: Dr. Martin Hesselius.”

Humbug, dear sir. The Chevalier Dupin can hardly be counted as part of the literary rabble. After all, what is Sherlock Holmes? Merely a British adaptation of Poe’s Gallic original.

Hi

Great topic I do like occult detectives and this is a nice overview.

I have to admit I am always surprised by the accolades Green Tea receives. While that may be, as you say one creepy monkey, the extraordinary efforts Dr. Hesselius goes through to insure that he cannot be called upon to assist Jennings destroyed any enjoyment the story might have held for me. Perhaps Hesselius is scared of or secretly in league with the monkey? Having said that I have read a number of the stories and authors you have discussed as well as others, the good the bad and the down right awful. A quick list includes the exploits of John Silence, John Thunstone, Carnacki , Lucius Leffing, Mile Pennoyer, Prince Zaleski, Cummings King Monk and Aylmer Vance. Boy just listing them demonstrates the fertility of the field. They are very much artifacts of their time with all the racism and misogyny of the period, as well as some generally bad writing. They share these characteristics with much of the early genre fiction writing in horror and science fiction sadly. But the other more mundane pastiches of Sherlock Holmes also often share these characteristics. My interests lie in the history of science fiction and what has come to be called the weird tale so I often read older works in the field.. As with history in general it has to be said that may of the people who were important in creating that history were not all that admirable.

Thanks for this.

Happy Reading

Guy

.”From out of this literary rabble emerged the very first occult detective: Dr. Martin Hesselius.”

Fitz-James O’Brien’s two tales about New York occult investigator Harry Escott have have chronological priority over Hesselius :

“The Pot of Tulips (1855): Escott investigates a ghost.

“What was It? A Mystery” (1859): Escott captures an invisible creature (This one had a strong influence on Bierce’s classic “The Damned Thing”).

Carnacki rules.

Not quite as lethal- Rudyard Kipling’s The House Surgeon . It’s suggested that ghost problems can be caused by bad drains. (It turns out to be a woman’s anger and resentment )

Very interesting and a somewhat less dignified Blackwood than we know from “The Willows” and “The Wendigo”. But did you not mix up “Ancient Sorceries” and “Secret Worship”? It is the later that has a silk merchant protagonist.

Entertaining, and we’d agree (maybe not quite so harshly) about Silence and Flaxman Low. As for Carnacki, we’d defend him as the first moderately efficient – and scientific – occult detective. Lots more about his enduring appeal, and his advantages over stuffy Dr Silence, here

http://greydogtales.com/blog/the-carnacki-conundrum-of-hogs-and-men/

P.S. I’m the editor of Occult Detective Quarterly, so have a vested interest. Cough.

But who — who — was the Canadian lumberjack detective? And was he OK?

@12,

He slept all night and worked all day.

Low doesn’t come off too badly at Baelbrow, attitude-wise: he takes Lena’s account seriously while the other males are chauvinistically dismissive. It’s Swaffam the gung-ho young banker who pulverizes the mummy, after prancing heroically around the house all night while Low keeps watch outside. Swaffam is definitely good White Street material.

These occult detectives would have been perfect for Hollywood, certainly well into the 1960s. I’m rather surprised there aren’t movies with these “detectives.”

As a side question, could one consider some of the current urban fantasy writers to be writing occult detective stories, e.g., Jim Butcher’s Dresden files and some of the earlier Laurell K Hamilton’s Anita Blake stories (before she moved to what could be categorized less as urban fantasy and more as urban sex fantasy), like Obsidian Butterfly?

“Defensive, condescending, full of made-up knowledge… well-versed in being obnoxious and making things up… relay[ing] a bunch of pseudoscience as patronizingly as possible…”

Dr. John Silence, the Godfather of Trolls?

@16: I was thinking about Harry Dresden when I got to the bit about Flaxman Low’s penchant for destroying buildings!

Regarding Silent, your article fails to mention how goddamn dull he is; I’d have been a lot more entertained with a chaotic mess of “Silent screws up then destroys the evidence” than the interminable plodding and endless wankery we get.

As for Carnacki, it’s not my favorite Hodgson story but they have the two advantages of being fast paced, and being willing to have a laugh on the hero.

The great Donald Pleasence played Carnacki in an episode of the ’70s UK anthology series ‘The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes’ titled “The Horse of the Invisible.” It’s worth checking out, as is the whole series.

I’m not sure why mummies are mysterious – the Victorians famously had a mania for Egypt which not only inspired rumors of a mummy’s curse sinking the Titanic – https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/everything-but-the-egyptian-sinks/ – but influences English language film and television to this day (cf. Penny Dreadful).

Readers interested in a balanced overview of occult detective fiction across a broader time period (from Poe to the 1990s) are referred to the article “Fighters of Fear,” written by Mike Ashley and annotated by Dave Brzeski, which may be found in Occult Detective Quarterly Presents: An Anthology of New Supernatural Fiction (2018).

#20, you beat me to it. I remember “The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes” on my local PBS channel in the 1970s. Although I’d swear the episode I watched was called “The Affair of The Tortoise,” “The Horse of the Invisible” sounds familiar too. Donald Pleasance was great.