We began the year with a post about the White Horse Between the Worlds: the ancient belief that a white horse (or a grey, as most white horses technically are) possesses mystical powers; that he (or she) can walk from world to world, and stands watch on the border between the living and the dead. Now, as the year ends and the Solstice is upon us, we’re back in that liminal space. In that space is one of my favorite films of all time.

I first heard about it from the Lipizzan community, which is small because very small breed, and everybody knows everybody else. Word was out that there was a film out, and there was a Lipizzan in it. That film was the 1992 Irish release, Into the West.

Of course I got to work finding a DVD, those being the days before streaming video (and that’s still true for this film: It’s not streaming anywhere, and finding a DVD when yours has gone walkabout is a bit of an adventure), and of course I spotted the Lipizzan right away. It’s in the first scene in the film, the chunky white horse running on the moonlit shore. That luminous coat, that high, floating action with tail streaming, that big convex head that would have been at home on a cave wall—oh yes. There’s all the earthy magic of the breed, right there.

And then the film gets underway, and we only get glimpses of the Lipizzan thereafter, but that’s part of the mystery, that the horse changes from scene to scene and sometimes from moment to moment. It’s a very Irish story, both modern and ancient. We move from the moonlight to the light of day, the old Traveller man with his bardo and his heavy cob camped on the seashore. The grey horse appears, but now he’s an Andalusian. He’ll be an Andalusian for much of the film, and sometimes a grey Thoroughbred-y type flying over fences.

Buy the Book

In An Absent Dream

The Traveller recognizes the horse immediately as a denizen of the Otherworld. He gives it serious side-eye, but makes no attempt to stop it as it follows him on his way—until it suddenly comes round in front and rears in stallion aggression.

And then we see what the horse is really doing battle against: A gigantic jet roars directly overhead. We’re out of the timelessness of the sea and the road and into the modern world.

The horse stays with the Traveller all the way into the seamy underbelly of Dublin, in what we in the US would call the projects. There we meet our human protagonists, the young brothers Ossie and Tito. They live with their father, scraping a barely legal living with other Travellers who have given up the road and settled in the city.

The Traveller is the boys’ maternal grandfather. Their mother died giving birth to Ossie. Their father was the King of the Travellers, but when his wife died, he left it all behind.

They all come together in the Traveller camp near the projects, and Ossie immediately bonds with the horse. Ossie, like his father, has “the gift,” the ability to communicate with horses; but his father has given it up along with everything else. Everyone accepts the horse as part of the scenery: The camp is full of them, and the camp kids ride them everywhere.

As modern and hardscrabble as the brothers’ existence is, it never lets go of its connection to the old ways and the old legends. The grandfather tells a tale by firelight of the hero Oisin—Ossie’s namesake—who fell in love with the queen of the Sidhe and was taken away to the Otherworld. But he never forgot where he came from, and eventually he convinced his lady to let him visit the mortal world again, but with one restriction: He must never dismount from his fine white horse, never set foot on the earth again.

Of course he does exactly that. As soon as he touches the ground, his mortality comes back to him, and he shrivels into dust.

This legend follows Ossie through the film. So does the horse, from whom Ossie refuses to be separated. When it’s time to go to bed, the brothers squeeze the horse into the elevator and take him up to their apartment. The neighbors are suitably appalled, but their father, on waking with a horrible hangover to find a horse standing over him, simply groans and rolls over and lets things happen however they will happen.

All too soon, the authorities get wind of this monumental public-health violation and show up to impound the horse. They find him getting a shower, with one brother on his back and the other wielding the spray, and rapidly discover that the horse, whom Ossie has named Tir-na-Nog (which is the name of the Irish Otherworld), is neither tame nor inclined to cooperate with anyone who is not Ossie. Tiny Ossie has to coax him down out of the apartment and load him on the van to be carried away.

He does so with the greatest reluctance, and with his father’s promise that he will get the horse back. But the effort fails. The fallen king is mocked and abused by a bad cop, and Tir-na-Nog is lost.

The bad cop, who observed the horse’s jumping talent during the police raid, has sold him to a rich man for a large sum of money. It’s not nearly as much as the horse is worth, as we can tell from the rich asshole’s expression as he departs with the horse.

The brothers know nothing of this, only that their horse is missing. They go hunting for him, put up signs and traverse the city, day after day.

In the midst of their search, they happen to catch a live television feed from the Dublin horse show—and there is Tir-na-Nog in the show-jumping competition. The next we know, the cops have their father again and are beating the crap out of him, until they finally get around to showing him why they hauled him in: a grainy video of the horse show. The horse suddenly blows up and dumps his rider, and when the camera is able to focus again, there are two small boys on the horse’s back and they’re headed for the exit.

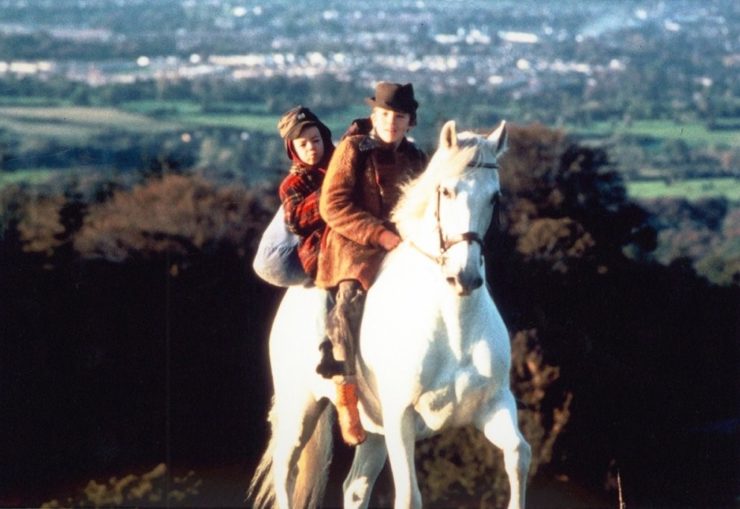

Then begins a long, wild chase across Ireland. The boys are running for a dream of freedom, far away into the west, where Tir-na-Nog comes from. The police are after them, the rich asshole is after them, their father has remembered his tracking skills, called in some of his old mates, and reconnected with an old lover, and is also after them.

Only the Travellers know the real danger the brothers are in. The non-Travellers just see that here is a valuable animal, and most buy into the idea that he’s been stolen from the rich asshole. One good cop recognizes that the boys are the horse’s real owners, insofar as this creature of the Otherworld can have any such thing.

And that’s what’s perilous. Tir-na-Nog is a cousin to the pooka and the kelpie, and it’s likely he was the white horse whom Oisin rode, who belongs to the queen of the Sidhe. He’s not in this world to be a child’s pet. He’s come to fetch Ossie, and he’s bearing him away toward the Otherworld.

For the brothers, ancient and modern blend together seamlessly. They’re devoted fans of American Westerns, and during much of their ride, they pretend they’re cowboys Going West, Young Man. One night they slip into a movie theatre, horse and all, and spend the night eating popcorn and watching horse operas.

As their wild ride goes on, they leave the city and the modern world behind and become more and more a part of the winter landscape, until they come to the sea. There the pursuit catches them at last: the police with their cars and their helicopter, and their father and his mates on horseback.

The horse bolts straight away from it all, drops Tito and carries Ossie into the sea. His father plunges after him, but it’s too late. He’s cold and he’s not breathing.

But there’s power in love, and it brings him back: He feels his mother’s hand drawing him out of the water. The horse is gone, though Ossie grieves. He’s done what he came to do. The queen (of the Sidhe or of the Travellers, or maybe both) has taken him back.

In the aftermath, it turns out there’s a little justice in the mortal world after all. The good cop exonerates the Travellers and punishes the bad cop. The boys and their father are free.

When night falls, the king bids farewell to his wife, burns her bardo and gives her a proper funeral. Then finally the family can move on.

For all the various human elements, the comedies and tragedies and the plain mortal messiness, the heart of the story is the white horse. He’s a messenger from the Otherworld, the catalyst to break the family out of its cycle of grief and loss. He weaves the worlds together. Sometimes hilariously, sometimes incongruously, and sometimes with the cold pure purpose of all high magic.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks by Book View Cafe. She’s even written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. Her most recent novel, Dragons in the Earth, features a herd of magical horses, and her space opera, Forgotten Suns, features both terrestrial horses and an alien horselike species (and space whales!). She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.

So is the changing breed of the white horse a story point or is it just assumed that non horsey viewers won’t notice?

@1 Nobody says anything. I like to think it’s a subtle nod to the magic of the horse.

Why wouldn’t a fairy horse be shapeshifty? Or maybe it’s all due to differing human peceptions.

@3 Exactly. I spend my life telling white horses apart (she has the silver mane on the left, she is the bigger left-maned one, she is the BIG one, she is the very round one, she is the one who looks like a cave painting…), so I can spot the changes. They make sense to me in the context of a horse from the Otherworld. Why wouldn’t he be different for different occasions?

I would have been 8 when we saw this, and I really didn’t understand what was going on a lot of the time, especially the Traveller culture – why it was good that they burned the wagon at the end… but it has definitely stuck in my head all these years. I should watch it again – I’m sure I’ll make more sense of it this time!

I remember the kids riding into the mountains and saying “It’s the Rockies!” And shopping for “cowboy food” when they were low on supplies – chocolate bars and beans. And there they were on a wanted poster! (Also, this is when I learned that if you put a can of beans on the fire without opening it, you will end up with a bean explosion…)

@5 It really is pitch-perfect, isn’t it?

I’m so glad someone else has seen this film! Its one of my favourites and survived the DVD cull. Love the horse in the lift scene best but the whole thing is totally magical.

Being from Dublin, seeing Ballymun called ‘the projects’ gives a moment of cognitive dissonance, but actually, you’re not wrong. They were built to move people out of disintegrating tenement housing in the city centre (mostly 18th century), but made the classic mistakes of not having facilities for the often very young population that moved in. The tower blocks have since been demolished in favour of mixed housing and the area is doing a fair bit better now, but there is still a chronic lack of shops and social facilities.

I don’t think any of the Travelers use the horse drawn wagons any more, but there is very much still a horse culture in the area, and in other parts of the outer Dublin suburbs – it’s more riding and sulky racing than anything else, though

@@.-@, I on the other hand probably couldn’t tell one white horse from the other, even if they were different breeds, unless they were standing next to each other. If then.

I just wanted to say I’m so glad I saw this article. For over a decade now I’ve been stuck with this image series from a movie with a white horse jumping and knew it was a movie I’d seen as a kid but couldn’t remember anything else from it or what it was called. Hitting the show jumping part here made me realize that THIS is the movie I’ve been struggling to remember.

@8 Thank you! I could not think what to call those things. Towers? Not council housing, surely. They look like that awful building in London that burned.

I’m glad they’re gone, though I hope all the people who lived in them had somewhere decent to go.

The Travellers in the film have nearly all gone on to vehicles and campers/caravans, if they’ve stayed on the road at all; many have gone on the dole, like the Murphy family with all its “extra” offspring. Only the traditionalists still have bardos. That’s part of the theme, that the Travellers have left the old ways.

@11 Tower blocks generally were (are) council housing. In the UK they were built post-WWII as urban regeneration replacing slum housing (or bomb-damaged housing stock). Unfortunately, the Brutalist style used for many blocks hasn’t worn well (looked good on the architect’s drawing board but had serious practical issues), and they quickly went from pristine ‘communities in the sky’ to slums worse than the slums they replaced. Now councils don’t have the cash to refurbish them and they can’t get rid of them fast enough. Grenfell (the tower block that burned) was a council refurbishment project and it’s thought the external cladding used was the major cause of the disaster.

Of course, my take on your synopsis – where on earth did they find a tower block with a working lift? (Quite apart from a lift that hasn’t been used as a toilet by the residents…)

For some reason I am sure this was a book too. I can almost see the cover, and I remembered much of the plot as I read this summary.

In terms of the otherworldly horse on TV/movies, I’m now remembering a favorite from when I was a kid – The Moon Stallion. The story was partly set around a blind girl, the White Horse chalk carving, legends of a white horse and folk magic.

This movie streamed on the late, great Filmstruck during its last few months extant, and thus I saw it. I hadn’t known anything about it until it appeared on the menu as part of a Mike Newell series. I’d liked Newell’s previous film Enchanted April, which I’d seen 1st run for some reason, and I always liked Gabriel Byrne & Ellen Barkin, since Defense of the Realm & Siesta, respectively. The movie didn’t disappoint.

Towerblocks would have worked just fine if politicians hadn’t targeted them for cost cutting and instead had used specced materials when building them, kept to the prescribed maintenance regimes, hadn’t fired the concierge and onsite janitorial staff, and used the genuine recommended decor instead of using cheap and yucky looking paint. Those were all necessities of the ideas behind tower living, and can be seen today in the towers that house the well off people, but if it were a choice between depriving the poor and making their lives worse, and a couple of pennies on income tax that the well off could easily afford… Well, it is easy to see why the poor had to take a hit for the greater good .

Just now finally ran across this post! I loved the movie Into the West, which I was lucky enough to see on the big screen when it first came out. I believe that in your last paragraph you capture the main theme of the narrative: the horse is the catalyst to break the family (esp the father) out of the cycle of grief. Or, as I would say, to free him from being stuck in the inability to grieve. He’s not stuck because he’s grieving too much or too long, he’s stuck because he’s not been able to do the work of grieving fully and effectively. Anyway, I loved the magical realism way of approaching this common issue, with the horse-between-the-worlds. And the way the ancient Celtic magic got merged with the boys’ cowboy/Western fantasy, so that the west of Ireland (towards Tir-na-Nog, which lies over the ocean to the west) became layered with the myth of the American West, child’s version.