One of the most compelling moments in George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire novels (and the era-defining television show that bears the name of the first book) is not one of the author’s signature shocking deaths, displays of unrelenting cruelty, or visceral battles. Rather, it is a quiet moment of expanding empathy wherein the audience is forced to acknowledge the complexity of a character who had, up until that point, served only as a font of villainy.

The character in question is Jaime Lannister, handsome son of privilege, whose incestuous relationship with his twin sister, casual maiming of a ten-year-old, and general aura of arrogant self-satisfaction when it comes to his martial prowess paints him as something as close to the primary villain of the first two novels as Martin’s capacious and complicated series can muster. And yet, in book three, A Storm of Swords, Jaime Lannister, a surprise narrator after spending most of the previous book imprisoned, reveals to his traveling companion that the very act that earned him the nickname “Kingslayer” and gave him the reputation of being a man without honor is, in fact, the noblest thing he has done in his life. Martin reveals that Jaime Lannister saved hundreds of thousands of lives by slaying the king he was sworn to protect, murdering the Mad King in order to prevent him from giving the order to burn the capital city to the ground.

In many ways, that moment changed not only the arc of Jaime Lannister’s character, not only the course of the novel, but the entire thesis of Martin’s series.

Prior to that, Martin’s seeming priorities had been with exploring the lives of the abject, powerless, and underestimated. Jaime’s brother Tyrion, all but parroting the author, explains “I have a tender spot in my heart for cripples and bastards and broken things.”1 Up until A Storm of Swords, the overwhelming majority of Martin’s narrators are people who were, by turns, loathed, pitied, or ignored by the vast majority of Westerosi society: women, children, bastard children, people with physical and cognitive disabilities, ethnic minorities, people who were too ugly, or fat, or queer, or frightened to be taken seriously by the world. Essentially, ASoIaF was an exercise in telling a story about power from the perspective of the powerless. By introducing Jaime Lannister as a narrator and forcing us to see not only his bleak future (wherein he reckons with his self-worth after the amputation of his sword hand), but his storied past as worthy of our consideration, Martin embarks on a bold new project: telling a story about political intrigue, bloody dynastic struggle, and personal power plays where no character is irrevocably beyond the reach of his readers’ empathy.

Five books and seven seasons into Martin’s narrative and HBO’s re-envisioning of it, we are given a story where no conflict occurs in which the reader feels truly, wholeheartedly on board with the outcome and the costs involved. We cheer Tyrion’s clever defeat of Stannis Baratheon at the Battle of the Blackwater, for example, while simultaneously being horrified by the deaths of Davos Seaworth’s sons as a direct result of Tyrion’s plan. This raises a number of thorny questions that are worth exploring here: how does Martin manage to make a narrative known for its uncompromising cruelty one in which there are so many characters with whom we can empathize? How can a television series faithfully render that cruelty visually and viscerally without further alienating viewers? What, precisely, are the limits of Martin’s project? Are there places where we as viewers and readers are no longer able to follow beloved characters?

Martin is relentless in his desire to humanize some of his most spectacularly unpleasant characters. A prime example is Theon, the ward of the Stark family and a character who, in the first two novels, exists primarily to underscore the perils of divided loyalty. While Martin is more than willing to explore the many nuances of what it means to be a political captive amidst a very nice family of captors, he also, in making Theon a narrator in A Clash of Kings, does not give the character much room to gain the sympathies of the reader. He sleeps with women he treats cruelly and gleefully abandons, turns on his beloved adopted brother for the sake of his cruel biological father, murders a number of beloved Stark family retainers when he captures their undefended castle, and seemingly dies having made poor leadership choices and having managed to inspire no loyalty.

Martin leaves Theon to an uncertain fate for the next two novels before bringing him back in A Dance With Dragons as the mutilated, traumatized manservant/pet of the sadistic Ramsay Bolton. At no point does Martin offer much in the way of an explanation for Theon’s previous behavior. His emotional abuse of his sex partners, betrayal of his family and friends, narcissism, and cowardice are all left intact. And this leaves the viewer with a thorny question: what does it take to redeem a thoroughly terrible person?

The TV series, with its necessary edits and need for visual storytelling, largely paints Theon’s redemption as the result of outsized physical torment. While the Theon of Martin’s novel is far more disfigured than Alfie Allen’s portrayal, the vast majority of Theon’s physical suffering is presented as nightmarish, half-remembered glimpses of captivity, all the more upsetting for their lack of specificity. When the show does attempt to give Theon a redemptive arc, it lays the groundwork somewhat crudely, having him soliloquize, early on in his captivity, “My real father lost his head at King’s Landing. I made a choice, and I chose wrong. And now I’ve burned everything down.”2 From there on out, the Theon of the show is given carte blanche to redeem himself by rescuing members of the Stark family, supporting his sister and, improbably, by beating up an Ironborn sailor who challenges his authority.

By contrast, A Dance With Dragons takes a much more roundabout and, in my opinion, more convincing route to building empathy toward the wayward Greyjoy scion; Martin puts Theon in the exact same position as the reader. Much of Theon’s plot in that novel involves a return to Winterfell, the Stark family castle which has been sitting abandoned and in ruins since the end of the second book. Theon is the only Stark-adjacent character present during these proceedings. As the ruined castle is filled with strange faces and new characters come to celebrate Ramsay’s wedding, Theon is the only character that can compare the Winterfell-that-was with his current surroundings. In Theon’s assessment, “Winterfell was full of ghosts.”3 That is likely the reader’s assessment as well, and Theon is made into a surrogate for the reader, bearing witness to and unable to alter the troubling misuse of a once-beloved space. Even in cases where Martin makes no apologies or excuse for his characters’ past behavior, he manages to force his readers into feeling empathy. The most vengeful readers of ASoIaF might have been cheering for Theon’s mutilation, but it is much harder to justify once they see him, and see through him, as their surrogate.

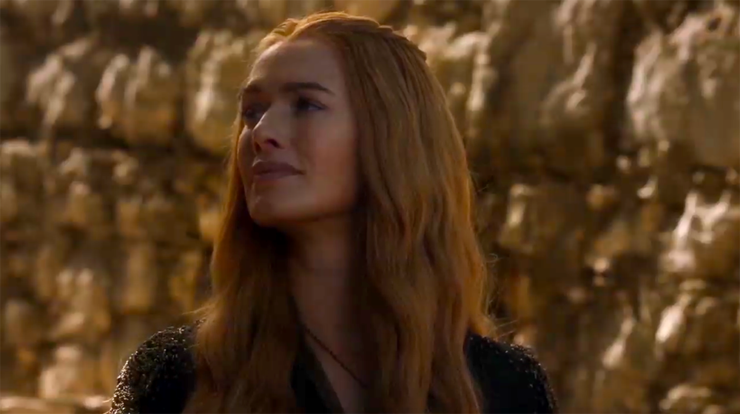

While the TV show has been forced by necessity to take an axe to many parts of Martin’s epic, impossible-to-completely-faithfully-adapt yarn, it has also, by virtue of its ability to explore the private lives of non-narrator characters, demonstrated its dedication to the same ever-widening gyre of empathy—deepening and expanding upon the foundation that Martin laid. Nowhere is this clearer than in the case of Cersei Lannister. Martin did eventually give us access to Cersei’s thoughts in his fourth entry in the series, A Feast for Crows, but the show has been dedicated to making the case for her complexity from the very start. In season one, episode five, Cersei and her husband, Robert Baratheon, two of the show’s more stubborn and intense characters, break into a surprising, vulnerable fit of laughter when the latter asks what holds the realm together and the former replies, “our marriage.”4

Just after that, Cersei reveals that she had feelings for her husband even after a series of miscarriages drove a political wedge between them and ends by asking, “Was it ever possible for us? Was there ever a time? Ever a moment [to be happy with one another]?” When Robert tells her that there wasn’t, she looks sadly into her wine glass and answers her husband’s query about whether the knowledge makes her feel better or worse by retreating back behind her icy glare and saying, “It doesn’t make me feel anything.”

In addition to being one of the most stunning, devastating scenes of the season, it confirms the truth of Cersei’s miscarriages, which she had previously brought up to Catelyn Stark (after having been complicit in making the rival matriarch’s son a paraplegic). It retroactively lends real complexity to that earlier scene: Cersei, even at her most ruthless, in covering up her brother’s attempted murder of a child is still able to empathize with that same child’s grief-stricken mother.

The Cersei of Martin’s novels is often identified by her motherhood. She is, prior to being made a narrator, often paired and contrasted with Catelyn Stark, a dark reflection of Catelyn’s fierce, relentless love for her children. Where Catelyn (before her death and resurrection, the latter of which, tellingly, does not occur on the TV show) is most often defensively attempting to protect her children, organizing rescue missions for her daughters, trying to safeguard her sons with marriage-based alliances, Cersei is the aggressor, allowing Bran to be silenced lest his witnessing of her incestuous relationship with Jaime call her own children’s legitimacy into question. She also ruthlessly kills off her dead husband’s bastard children in order to grant legitimacy to her own; an act that the show rewrites to be the explicit order of her son, Joffrey—sparing her character any further dabbling in infanticide.

By contrast, the show expands Cersei’s role from “mother” to “woman.” She ends up speaking, not just for the impossibility of being a laudable mother in a patrilineal world, but for the impossibility of being a woman with any self-determination in a patriarchal rape culture. In another moment invented for the show, Oberyn Martell, one of Westeros’s few male, woke feminists, assures Cersei that “We don’t hurt little girls in [his kingdom of] Dorne.”5

She responds with a line that’s produced endless memes and feverish hot takes across the internet: “Everywhere in the world they hurt little girls.” This line may as well serve as a mantra for many of the show’s detractors who, rightly, point out the series’ preoccupation with the objectifying male gaze in its focus and presentation of female nudity as well as its propensity to use graphic rape as a transformational plot point for its male characters. But, from another perspective, it could be argued that this is also the show undercutting the male power fantasy that a viewer might mistake for the central point. And the show gives this line to Cersei—a character who spends much of her narrative arc ordering acts of repellant cruelty and steadily alienating her allies.

The show even goes so far as to make a meta point about the power of expanding empathy in the show’s sixth season, where troubled teen Arya Stark—who nightly whispers a prayer that includes a call for Cersei’s death—is forced to reckon with her own capacity for empathy when she watches a play that dramatizes the death of Cersei’s eldest son. This mirrors a pre-released chapter from Martin’s as-yet-unpublished The Winds of Winter. The difference seems to be that, in Martin’s prose, the content of the play is never explicitly stated, and hinted at only as a winking reference to careful readers, whereas the show’s handling of the material clearly marks Arya’s viewing as a powerful moment of identification that triggers her own traumatic memories of watching helplessly as her father was killed.

It is a stunning achievement, both in terms of the show and in the novels, that so much empathy can be generated alongside events that regularly feature acts of murder, rape, torture, and cruelty. If we are to take the moral philosophy of Richard Rorty to heart, it is the last of these that presents the most difficult hurdle in Martin’s ongoing project. Rorty famously believed that the complexities of moral philosophy could be more or less predicated on the notion that to act morally was to act without intentional cruelty.6 Clearly, the worlds of ASoIaF and GoT do not operate on this most basic of principles. So how do we assess Martin’s view of who we can and cannot have empathy for?

Buy the Book

Warrior of the Altaii

It is worth noting that Martin’s world contains a large number of what we laypeople might diagnose as sociopaths. From the mad kings Aerys II Targaryen and Joffrey Baratheon, who are given unfortunate influence because of their position, to those who have risen high because of their lack of empathy like Ser Gregor “The Mountain” Clegane and Vargo Hoat (called “Locke” in the TV series), to those who have been so systematically poorly educated, abused, or smothered by their upbringing that they never had the chance to develop a sense of empathy like Ramsay Bolton and Robert Arryn (Robin Arryn in the TV series), the list of characters who have tenuous to non-existent relationships with basic empathy abound. It is striking that, in the case of most of these characters, Martin and the showrunners have been clear in their commitment to providing us with reasons for their irredeemability. We may not empathize (or even sympathize) with Ramsay Bolton… but we are told that his overwhelming cruelty is the partial product of his father’s attempts to make him so by dangling the legitimization of his bastardy over his head, forcing us to consider him as a sort of Jon Snow gone horribly wrong. Similarly, if we can’t precisely muster any sorrow for the death of Joffrey, we do grieve for his mourning parents. The show especially offers us a moment of terrible internal conflict when he chokes, crying, in his mother’s arms in an intense close-up, daring viewers to not feel at least some quiet pang of pity. Martin’s sociopaths are almost always portrayed as forces of nature rather than personalities. They are storms of violence that descend upon hapless characters, and we are rarely given moments of moustache-twirling clarity where we both understand that they are monstrous and simultaneously understand that they have free agency and forethought in their actions.

If Martin has a cardinal rule about where our empathy cannot follow, it does not lie with those capable of cruelty. Rather it lies with those who, in a clear-thinking way, use the cruelty of others to achieve their ends. Roose Bolton, Ramsay’s father, is one of the few truly, uncomplicatedly irredeemable characters in the series, and his villainy stems entirely from his willingness to use his son as a weapon of terror against his enemies. Similarly, while Martin and, especially, the show’s portrayal by Charles Dance, are willing to extend some humanity to ruthless patriarch Tywin Lannister, his primary role as villain is often explicitly tied to his tactical decision to deploy his “mad dogs,” monstrous bannermen and mercenaries, to keep others in line.

Even in cases where the show and books diverge, the moral line remains the same. The show’s version of Littlefinger, played with finger-tenting, melodramatic glee by Aidan Gillen, is far less subtle and somewhat less sympathetic than his book counterpart. The show gives Littlefinger his bravura moment to revel in villainy in a season three episode where he proclaims, “Chaos isn’t a pit. Chaos is a ladder. […] Only the ladder is real. The climb is all there is.”7 This speech is given over a montage of images that reveal, among other things, how he used Joffrey’s fetish for violence to dispose of sex-worker-turned-spy, Ros, foiling his rival’s attempts to gain influence in the court. The principle remains the same: the most unforgivable sin is the knowing and calculated exploitation of someone else’s cruelty.

The narrative even goes so far as to suggest (at least in the lore of the show) that the ultimate antagonist, the undead Night King, is a press-ganged living weapon created, in desperation, by the environmental stewardship-minded Children of the Forest. The big bad being nothing more than the tragically overclocked remnant of an extinct race’s last-ditch effort to save humanity from itself feels like the most George R.R. Martin-ish of plot points. The Night King must be destroyed, but he truly can’t help himself.

In looking at the almost comically long list of Martin’s characters, particularly those we are invited to connect with, it is almost more surprising that we do not question our empathy for some of the “heroic” figures more regularly, given the morally gray scenarios, compromises, and behaviors that Martin writes for them. I have gone this far speaking mostly about characters that generally play a more villainous role. We have not even touched on fan favorites like Tyrion Lannister, who murders his former lover in a fit of rage at her betrayal, or Jon Snow, whose loyalty to the Night’s Watch involves his complicity in luring his lover south of the Wall where she is killed by his compatriots, or Arya Stark, who—especially in the show—stares out from an expressionless mask, killing dozens without question, or Daenerys Targaryen, the ostensible, projected winner of the titular game, who regularly tortures her enemies then burns them alive all while deputizing violent strangers and avaricious mercenaries to oversee the cities she has liberated. The world of Game of Thrones offers so many characters, from so many different backgrounds, for readers to feel sympathy for, live vicariously through, and otherwise identify with that the list above is one comprised of characters we mostly don’t even argue over.

As we anticipate the final season later this month, it is worth understanding that the show is one that has carefully taken inspiration from its source material to create impossible situations where no resolution can feel uncomplicatedly triumphant. Every moment of satisfying revenge or conquest is also potentially a moment of complete devastation for a character we feel a great deal of empathy for. With the cast whittled down to a respectable number, almost none of whom can be written off as irredeemably bad, I find myself watching with a kind of dread for any possible outcome. Any ascension to Martin’s most uncomfortable of chairs necessitates the loss—likely the violent and cruel loss—of characters we have spent nine years (or, in some cases, twenty-three years) coming to love.

Tyler Dean is a professor of Victorian Gothic Literature. He holds a doctorate from the University of California Irvine and teaches at a handful of Southern California colleges. More of his writing can be found at his website and his fantastical bestiary can be found on Facebook at @presumptivebestiary

[1]Martin, George. A Game of Thrones. Bantam paperback edition, 1997, p. 244.

[2]“And Now His Watch Is Ended.” Game of Thrones, created by David Benioff and DB Weiss, performance by Alfie Allen, season 3, episode 4, Bighead Littlehead Productions and HBO, 2013.

[3]Martin, George. A Dance With Dragons. Bantam mass market edition, 2013, p. 598.

[4]“The Wolf and the Lion.” Game of Thrones, created by David Benioff and DB Weiss, performance by Lena Heady and Mark Addy, season 1, episode 5, Bighead Littlehead Productions and HBO, 2011.

[5]“First of His Name.” Game of Thrones, created by David Benioff and DB Weiss, performance by Lena Heady and Pedro Pascal, season 4, episode 5, Bighead Littlehead Productions and HBO, 2014.

[6]Rorty, Richard. Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

[7]“The Climb.” Game of Thrones, created by David Benioff and DB Weiss, performance by Alfie Allen, season 3, episode 6, Bighead Littlehead Productions and HBO, 2013.

I always liked, especially in the show, how they contrast Danaerys and Cersei. While the Targaryen princess is widely assumed to be one of the heroes of the story, she often acts like a villain and nobody seems to mind or care, and instead they heap praise upon her for being a good ruler, and though the Lannister queen is a horrible person and a worse ruler, she sometimes has these small moments where she’s shown as not completely and without exception the worst person ever.

Yes, but it’s about motivations. Dany has mostly heroic motives and a sympathetic origin story. Powerless under the thumb of her sadistic brother, sold as a child, and now fighting so that other children will never be slaves… that is a compelling, hero-coded narrative. Not to mention the whole “rightful princess comes back into her own” plotline. Even when Dany acts like a villain, it’s clear that this is not because her motives are impure, but because the harsh reality of the world, and of governing justly, is causing her to try and take “villainous” shortcuts. In fact, the tendency to autocracy which many villains exhibit can be explained by this. Sauron fell from grace because he wanted to make the world a better place, and wanted the power to do it quickly.

Cersei is the opposite. Her motives are universally selfish and cruel, even when she’s coming from a similar place of powerlessness. Yes, what was done to her in forcing her to marry Robert was unjust, and her anger and bitterness are understandable. But it’s made clear that her solution to this involved using her twin brother to alleviate her own pain with no thought to his happiness. She’s right to protect her kids, but she cares more about her own power. All of the hero-coded and sympathetic actions she takes are in reality selfish; her kids are extensions of herself and valuable for that reason, not as actual people.

And her murder of her childhood friend makes it clear this is not a fault of “the patriarchy” but an innate selfishness and cruelty. Her experiences in life may have exacerbated that, but she was going to be an evil person no matter what.

For Theon and Cersei, I have little symapthy, aside from the general sympathy for their upbringing and whatever horrible things happened to them. Thing is, especially in Theon’s case, simply going through awful things does not equal ‘redemption’. It may be that he’ll actually feel sorrow and contrition, but for me the character crossed the moral event horizon when he was willing to murder two unrelated children to keep up his ruse (not that he hasn’t done other awful things before and after).

Likewise with Cersei – yes, she is unfortunately a victim of the patriarchal structures in which she lives, and has undergone the objectively terrible ordeal of all of her children dying. But she’s also hardly some champion of women’s rights. What she’s really upset about is that SHE did not have power.

Jaime, I do think has shaped up to be a convincingly conflicted and well rounded character (even if he still has plenty to atone for), but YMMV on that.

I have no sympathy whatsoever for Theon or Cersei. Of course Theon doesn’t deserve Ramsey; nobody does. But what he did was both selfish and cowardly, as well as horrific. He gets nothing.

As for Jaime, well, in the books he hasn’t yet done any good. Even in the show the best we can say is that the path to redemption is open to him and he may yet walk down it. But I’m not ready to forgive what he did to Bran.

@2: I agree with you, but “I didn’t mean to” is what children say to avoid taking responsibility for the consequences of their actions. While one can hardly argue that Dany is not a much better person in every respect than Cersei, I’ve never really liked the character for the most part, even back in the day when the books first came out and I dreaded reading her p.o.v. chapters. I dislike the way she pretty much acts like a tyrant whatever her intentions may actually be, and we’re supposed to root for her, and a lot of people actually do, both in the book and in real life. I guess GRRM is doing it on purpose, but it’s ironic how we’re told all the time about how horrible Targaryen rules can be (like her grandfather or her brother Viserys), but she’s not doing stuff much differently than they would, at the end of the day. Other “hero/good” characters, like Jon Snow, Brienne of Tarth, Sam Tarly or Ned Stark, screw up despite their good intentions, but they seldom do it out of pettiness like Danaerys often does. She’s more akin to Catelyn Tully or even the Lannisters than to the other really “good guys” we’re supposed to lump her with.

What is more interesting is that he had never told anyone about his motives for doing that, although he could have shown them the vats of wildfire as proof. It is as if he wanted to be despised, or at least thought he should be.

He explains why he did that, though, doesn’t he? It was an ego thing, basically. He says that after he killed the mad king, Ned Stark and some other dudes came into the throne room and Ned sort of accused him of wanting to sit on the Iron Throne himself, so he was offended by the “good guys” automatically thinking the worst of him. Then people started calling him Kingslayer and Oathbreaker and he chose to refuse to try to explain himself to the world, feeling he owed them nothing. At least that’s more or less how I remember it, it’s been years since I read that book or watched that season of the show (heck, I don’t even remember if he actually explains this part in the show).

As I remember it, Ned came in and found Jaime actually sitting on the Iron Throne. Ned didn’t say anything, just stared at him, and Jaime vacated the chair. Like you, it’s been quite a while since I read it so my memory could be off.

@8: As far as I know, the only other person who knows about the wildfire is Brienne, because he killed anyone who knew about the scheme, including the pyromancers who were supposed to set the whole thing off. Unfortunately, this also makes for a sticky situation in the long run, considering how delicate wildfire is said to get as it ages. Some people have speculated that those remaining caches are going to be set off in the future, either on purpose by Cersei or accidentally by Daenerys,

Really strong analysis. Would love to see more from this author.

Good essay!

This is great. I am an avid fan. I think this essay takes the books and the program as seriously as I do.

What an astute and well-considered take on this series. I absolutely agree that it is the extent which Martin builds characters, rather than archetypes and plot devices as can sometimes happen in genre fiction, that makes both the novels and HBO series unique for their ability to facilitate empathy. However, I personally find it much easier to empathise with the many characters who are self-aware of their complexities. This makes Daenerys a challenging figure for me, as she seems to genuinely believe that she is the conquering hero her narrative would typically have her be, in spite of the many monseterous things she’s done. Perhaps I’m forgetting a scene where she meaningfully acknowledges with this, but if I’m not I hope this will be forthcoming.

Wonderful analysis. I’d love to read a series of essays on ASOIAF by the author. Thanks for the great read!

This is a great analysis of the supreme achievement of GRRM/HBO’s project — and also what makes it so exhausting and traumatic to consume. I still have waking nightmares about the Mountain vs. Viper scene.

This is wanting me to try and catch up before the series ends!

As a result of Mr. Martin’s writing skills, while I may feel some pity for Cersei and Jaime and Theon; it is to the extent of wishing a quick and relatively painless execution for them rather than prolonged suffering:

I am not counting the characterization of Cersei in the show; the writers there have made her a slightly gentler person and omitted some of her crimes.

In the books, Cersei has, it is strongly implied, sent two innocent children into slavery because they were sired by her husband Robert; and also ordered the murders of all of Robert’s illegitimate children in King’s Landing. As a young girl, she probably pushed her companion down a well; she does remember hearing the girl’s screams for help and not telling anyone where she was. Cersei believes that one of her maids is a spy and, although there is no proof, she hands the girl over to Qyburn for use in his horrific experiments. She does the same thing with a noblewoman who was her ally; when the woman becomes useless to Cersei and is requesting her help, she gives her to Qyburn for disposal. At this point, any pity I had for Cersei as a pawn in Tywin’s marriage games and a battered wife dissolves.

Theon does suffer horribly in Ramsay’s hands and does manage to save the beaten and tortured Jeyne from Ramsay. That does not negate the fact that Theon murdered two little boys and their mother. I hope Stannis gives him a him a quick death rather than burning him alive.

I have yet to hear Jaime say, in the books, that he is sorry for trying to kill Bran Stark and crippling him instead. Does Jaime go on a quest to help Bran’s only relative believed to be alive, Sansa Stark, in atonement? No, he palms off a redemptive act on Brienne so he can still serve the Crown and what is left of his family. As for Jaime’s supposed great act of nobility in killing Aerys to save the people of King’s Landing; Jaime was also saving himself, since Aerys was ranting about blowing up everyone, himself included; and said nothing about releasing Jaime to save himself (if there had even been time for Jaime to ride out of King’s Landing before the wildfire went off). The young Jaime may have been horrified by the impending slaughter of thousands, but his own life was also at risk; so I’m not sure how his killing of Aerys and a pyromancer or two qualifies as a purely altruistic deed. Also, Jaime was an accomplished knight and fighter even at 17; he could have incapacitated the raving Aerys, killed the pyromancers, thrown Aerys in a cell and delivered the king to his father, avoiding personally murdering the king he had sworn to protect. Jaime deserves a quick execution or a life at the Wall; his supposed redemption is a bit too little, too late.

I always saw Cersei as a fairly powerful character — not compared to the men in her family, but compared to pretty much everyone else in the books — and thought of her tragic flaw as not being smart enough to leverage her position. She is selfish and cruel, but so are lots of people in Westeros; more importantly, she’s not able to master those impulses in service of the long game. Imagine Cersei but with Tyrion’s ability to read a room, predict the consequences of her actions, learn from her mistakes. It’s like she’s got a flashlight and keeps shouting at it “WHERE’S MY POWER I WAS SUPPOSED TO HAVE POWER” but doesn’t realize she has to put batteries in for it to do her any good.

17 sums it up quite well.

Jaime Lannister isn’t really an exception to the powerless narrator pattern; he becomes a narrator after losing his hand, which renders him powerless. His story is then one of walking in another’s shoes, and becoming “woke” to the position of the other narrators in this society- bastard children, abandoned/manipulated/used children, women who have decidedly non-traditional roles, the physically different, etc. His power as a narrator comes from his loss of power as a warrior prince, and becoming one of the people he previously despised (or at least felt superior to).

Martin does love a heaping dish of irony.

Never had any sympathy for Theon, Cersei and many others in this series, and I see Dany’s arc more as innocence lost than aught else. Until her bath in fire and her dragons were born, she was a scared little girl who wanted nothing more than to return to the house with the red door. Her transformation to the Queen she becomes is harsh, yes, but this is a harsh and indeed, a male dominated world she is in. Does she become more cruel? Sure. Are all her actions heroic? Of course not. The fact remains she is forced to become The Dragon Queen, otherwise she’d be dragged under by the male dominated world she lives in.

To me, a far more egregious thing has occurred in the transformation from book to TV series. That is to say, 90% of the black humor from the books is nowhere to be seen in the show. And that is a loss. Yes, lots needed parking, especially the sheer number of characters/plotlines to make it a viable TV product. That said, I don’t care about most of the TV characters because so much of what made them appealing is just not there.

Tyrion and Littlefinger are prime examples of the lost dark laughter in the show. Even worse, Tyrion, who is supposedly soooooo much like his father, is a mere clown in season 7, getting outmaneuvered by everyone. Hardly a thing Tywin was known for. He isn’t amusing me with all manner of quip either–the show writers have ripped that away along with any battle cunning he had. Petyr Baelish, he was FUNNY as hell in the books. One step ahead of everyone and mocking them all. By paring down the plotlines and characters his role is changed dramatically from a scheme who wants to be the power behind the throne–a man who knows his bloodline will NEVER let him rule the 7 kingdoms–to a bad joke of a dullard who somehow thinks he can be ruler. And he is rendered dull without the trademark black humor from the books. I was relieved when he was killed off, I just couldn’t take much more of his mournful boring person by then.

Which brings me to Varys. He was a complex and hard to read fellow in the books, jumping from seeming okay to evil in mere pages, possibly even a sorcerer. For some reason he is being cast as more of a misunderstood hero type than villain in the TV series. Practically teleporting all over the world like so many other characters, but instead of being a dark character, he is a…I suppose on the side of good.

The show has done a lot of damage to the story arc, imo, and no where do I find this more evident than when Qyburn kills off the Grand Putz, er, Maester instead of the book-competent Kevan Lannister. The Grand Maester was an old and ineffectual fool who could be counted on to fold like a cheap deck chair under the slightest pressure from the Lannisters. There was no need to kill him off, even in the shows he wasn’t doing anything useful. Hardly the impediment that the book version of Kevan was. Though he was pretty much turned into a court today rather than the career soldier he was in the books.

@21: I agree about the show changes, though Pycelle did get killed along with Kevan in the book; the show shoehorning his murder in via Qyburn was rather inconsequential.

I haven’t seen the show’s most recent two seasons, only read about them on the decidedly biased-against-it Fandomentals website. But even from what I have seen, I think the show and the book have radically different takes on compassion and cruelty. Many people consider ASOIAF and GOT to be stories where no good deed goes unpunished and no bad deed goes unrewarded. But in the books, foolish deeds get punished and clever decisions are more likely to get rewarded — a clever person can live a long life before making one foolish decision, out of kindness or cruelty, and dying for it. (Sheer good or bad luck prevents this from being a given, though). True, sparing or saving someone’s life often gets many people killed, though often not the person who did the saving/sparing. (Roose spared baby Ramsay, Victarion spared Euron, Catelyn saved Littlefinger, Arya saved Jaqen, Rorge and Biter, etc. etc.). And poor Dany’s efforts do do right by “her” people cause infinite suffering. But it’s made clear that vengeance is a pointless, ugly, self-perpetuating thing that undoes no wrongs and only gets more people killed, occasionally satisfying to readers *points at House Manderly sigil* but wholly harmful in-world.

In the show, by contrast, good deeds are inevitably punished and bad deeds spectacularly rewarded. Anyone who acts in compassion — including show-only characters like Lady Crane, Septon Ray and his crew, and the Winterfell woman who tried to help Sansa — is likely to get killed in short order. And people who openly slaughter their their leaders and/or families — capitol crimes even in Westeros — get rewarded with power and approval, at least in the short term. (Most kinslaying in ASOIAF is done with some degree of secrecy for plausible deniability). And the righteousness of bloody vengeance goes unquestioned.

@@@@@ jmhaces – what “petty” things does Dany do? I can’t recall many, at all.

My latest on how empathy is what makes Game of Thrones transcendent (despite that last episode). PLZ SHR! @GameOfThrones https://realcontextnews.com/game-of-thrones-and-the-gift-of-empathy/