In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

In the 1960s, a time when female voices were underrepresented in science fiction, Anne McCaffrey was an exception. McCaffrey’s most famous books were the Dragonriders of Pern series (currently the subject of a Tor.com reread led by the incomparable Mari Ness). But, while the subject of only six short tales, one of McCaffrey’s most memorable characters was Helva (also called XH-834), who became known throughout the galaxy (and science fiction fandom) as The Ship Who Sang.

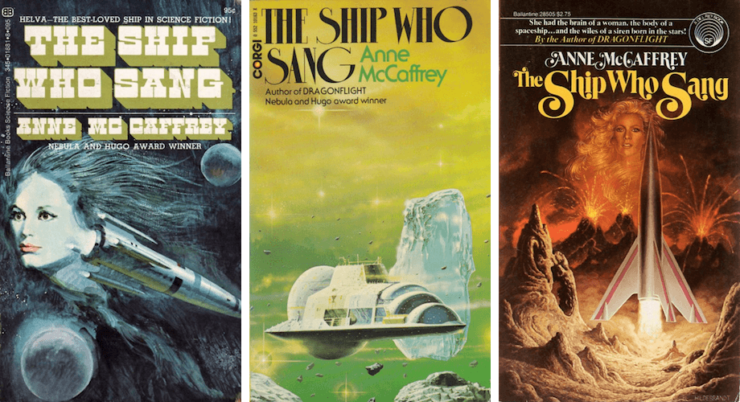

In researching this article, I was surprised to find that the tales incorporated into McCaffrey’s The Ship Who Sang fit into a single, slim volume. While there were more books written with co-authors at a later date, McCaffrey wrote all of these initial tales alone, and while they are relatively few in number, they had a large impact. I encountered the first story in an anthology, early in my reading career, and others when they appeared in various magazines. The stories were memorable, and Helva was a sympathetic and compelling protagonist. I remembered them for years, long after I’d forgotten many of the other tales I read in that era. McCaffrey didn’t produce a large quantity of stories about Helva, but those she wrote were of the highest quality.

About the Author

Anne McCaffrey (1926-2011) was an American science fiction writer who spent her later years living in Ireland. Her career spanned more than four decades. As mentioned above, she is most widely known for her Dragonriders of Pern series, a science fiction epic that started with a single story in Analog magazine, something that surprises many fans, as the series has many of the trappings of fantasy fiction. The series eventually grew to encompass 21 novels, with later volumes co-authored with her son Todd.

She is also known for her Brain & Brawn Ship series, which followed the adventures of ships guided by the brains of humans who have such severe disabilities they cannot survive outside a life support cocoon within the vessel. These titular “Brains” are paired up with unmodified humans (the “Brawns”) who perform physical tasks that are required to achieve the ships’ missions.

Buy the Book

Empress of Forever

The Ship Who Sang, which was published in 1969, is more of a collection of stories integrated into a “fix-up” than a straightforward novel, with most of the chapters being reworked versions of tales first published in short story form, though the last chapter is original to the book. The short story “The Ship Who Sang” was one of the first stories McCaffrey ever wrote, and was published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 1961. It was also selected by editor Judith Merril for one of her Year’s Best anthologies in 1962. The other stories that made up chapters in the novel first appeared in Analog, Galaxy, and If magazines. Under the sponsorship of Baen Books, the Brain & Brawn series eventually grew to include six additional novels, four written by co-authors working with McCaffrey, and two more written by the co-authors alone.

McCaffrey also wrote novels set in the Acorna, Crystal Singer, Ireta, Talents, Tower and Hive, and other universes, along with some solo novels and short story collections. She was the first woman to win a Hugo Award, and the first to win a Nebula Award (in 1968 and 1969, respectively). Because of the strength and popularity of her entire body of work, she was recognized as a Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America Grand Master, and inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame.

Brains and Cyborgs

Disembodied brains have been a staple of science fiction since the early days of the genre. Often the subject of horror stories, they have menaced many a protagonist with their advanced mental powers. Becoming a cyborg, with one’s brain embedded in machinery, or with devices grafted onto a human body, was often presented as a fictional fate worse than death. Characters would implant mechanical devices in their bodies to give themselves additional abilities, often with malevolent intent. The evil biological/mechanical hybrid Borg of the Star Trek series are just one of the many incarnations of this trope.

In McCaffrey’s world, however, the melding of man and machine was seen in a much better light. Becoming a “shell person” or “encapsulated brain” is presented as a positive, humane opportunity for people with severe physical disabilities, allowing them to develop their exceptional talents and intelligence. At that time, when even the simplest of computers filled entire rooms, and even the most forward-thinking stories depicted characters using slide rules on the bridges of their spaceships, using a human brain for complex tasks seemed more likely than using some sort of mechanical intelligence. So McCaffrey postulated a universe where spaceships, and even cities, were managed by human brains linked directly to electrical and mechanical control systems, able to manage complex systems as instinctively as they might their own bodies. And she even anticipated the controversies inherent in the concept, projecting that there would be societies who opposed humans being used in this manner, and other groups who would work to protect their rights and prevent their enslavement.

(Incidentally, if you are interested in more information on theme of cyborgs, and a list of works that incorporate the theme, you might start with this Encyclopedia of Science Fiction article on cyborgs.)

The Ship Who Sang

The first chapter bears the title of the collection, “The Ship Who Sang.” It starts with Helva’s birth, and guides us through the early years of her life, as she is prepared for life as the guiding intelligence, or “Brain,” for a starship. Modern readers might be surprised by this somewhat leisurely approach to the narrative, as current styles call for dropping the reader into the midst of action, and for “showing” rather than “telling.” But it is the story that is most compelling, here, not the prose. From the start, Helva proves to be clever and intelligent. And she takes a particular interest in music, using her mechanical abilities to sing in ways that are beyond the abilities of a normal human. She is approached by a “Brawn,” a man trained as a partner for a brainship, and decides to invite more of his counterparts aboard so she can choose a partner carefully. And she is taken by one in particular, Jennan, with whom she falls in love. The feeling is mutual, and they form a deep attachment. But during one of their earliest missions, in an effort to save colonists from an overheating sun, Jennan sacrifices himself so that more colonists can be saved. Helva sings her loss. The story is compact, but deeply moving. Despite the oddities of her situation, we empathize with Helva as a human, and we grieve with her.

The second tale is called “The Ship Who Mourned,” and we find Helva still grieving the loss of Jennan. She is temporarily partnered with a medical officer named Theoda—not a Brawn, but a physiotherapist picked for a specific mission. They travel to a planet gripped by a plague that leaves victims paralyzed and uncommunicative. Theoda comes from a planet that faced a similar malady, and finds that the patients can be treated with physical therapies. (Anachronistically, and despite her professional credentials, her efforts are originally dismissed as “woman’s intuition.”) It turns out that Theoda lost her entire family on her home planet. Through working together on their mission and sharing their losses, Helva and Theoda find some comfort.

The third story, “The Ship Who Killed,” opens with Helva taking on another Brawn, this one a young woman named Kira. Their mission is to collect embryos from around the galaxy, three hundred thousand of them, and take them to a planet whose population had been sterilized by an ecological catastrophe. Kira is a personable companion and a “Dylanist,” someone who uses songs to promote social justice. (I have never been a Bob Dylan fan, and found the idea of him inspiring such a movement a bit preposterous.) It turns out that Kira has lost her mate, and before they could freeze any embryos, so she is grieving, just as Helva still feels the loss of Jennan. They are ordered to proceed to the planet Alioth, which turns out to be ruled by religious fanatics, and trouble ensues. They find themselves in the clutches of a death cult that worships an insane brainship. And Helva finds that she must use her musical abilities and what she has learned from Kira about the power of song to save them both, along with the people of the planet, from destruction.

The fourth tale is called “Dramatic Mission,” which I first thought would be about a mission with lots of dramatic events occurring. Instead, Helva is tasked with transporting a drama company to an alien planet, where they will put on plays in return for the aliens giving technological secrets to the humans. She is currently partnerless, as her three-year “stork run” with Kira has ended. The drama company is full of conflict, with a leader who is a drug addict close to death, and a female lead picked more for political than professional reasons. When the company, who are preparing Romeo and Juliet, find that Helva knows Shakespeare, she is drawn into playing a role. And at their destination, they find that the aliens can download personalities into alien bodies, and Helva finds herself for the first time in a physical body outside her shell. That process turns out to be very dangerous for humans, and they soon find themselves ensnared in a web of betrayal and hatred that pushes Helva to her limits.

The penultimate chapter is “The Ship Who Dissembled.” Helva is partnered with the infuriating Teron, who has proved to be a terrible Brawn. And to make matters worse, she had picked Teron over the objections of her officious boss, Niall Parollan, and doesn’t want to admit that he was right. Brainships have been disappearing, and at one of their stops, Teron allows some officials aboard over Helva’s objections; these officials then kidnap them, although Helva has left an open channel with Parollan that might offer a chance for rescue. Helva finds herself stripped from her ship and left in a state of sensory deprivation. She is with the Brains of other captured ships, and some of them have succumbed to insanity under the stress. With no resources other than her wit and her ability to synthesize sound, Helva must find a way to foil her captors and save the day.

Buy the Book

The Ship Who Sang

The final story, written specifically for this volume, is “The Partnered Ship.” Helva has earned enough credits to pay off her debts and become an independent entity. But Parollan and other officials bring her an offer. If she agrees to extend her contract, she will be fitted with a new, extremely fast star drive, the fruit of the trade with the Shakespeare-loving aliens. Parollan, however, is acting strangely during these negotiations… It turns out that he has long had a crush on Helva. Despite the fact that they bicker constantly, she is flattered by his ardor, and feels he brings out the best in her. So, finally putting behind her loss of Jennan, Helva takes on a more permanent partner, and looks forward to an exciting new life on the far frontiers of space.

As a young reader, I was mostly drawn by the adventure aspects of these stories. But as an older reader, I was struck by the depth of the emotions they portrayed. They are deeply moving meditations on love, loss, perseverance and rebirth. While McCaffrey is a competent writer of action stories, in these tales she wears her emotions on her sleeve in a way that her contemporaries generally did not, and the stories are stronger as a result.

Final Thoughts

The Ship Who Sang represents a small portion of Anne McCaffrey’s body of work, but because of the strength of those stories, the book is often mentioned as some of the best of her fiction. There are some aspects of the stories that feel a bit dated, but they remain as powerful today as when they were first written.

And now it’s your turn to comment: What are your thoughts on The Ship Who Sang? How do you feel it ranks among the author’s other works? And are there any other tales of cyborgs that you found as memorable as Helva’s adventures?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

I’d forgotten much of Helva’s adventures apparently. I think I only re-read some of the later books, notably the City Who Fought. I’d be interested in commentary on these books about how they deal with issues of disability. Though it seems they were not visited by the suck fairy, at least.

The idea of a person interfacing with a ship seems to have stuck with me though. I’ve had assorted story ideas with that as a central concept. It’s pretty appealing to have access to senses and ability beyond one’s fleshly form.

The common trope surrounding a brain-vessel interface, I think, that it is permanent. McCaffrey would probably be a pioneer here, but later works show the same tendency, WH40K and Honeworld to name some.

I’ve loved Anne’s work since I was a pre-teen in the early 80’s. I tell people that if you want to read her three best works, you have to go with “Dragonflight”, “Crystal Singer”, and of course, “The Ship Who Sang”. I recently got a cheap ebook copy and reread it and I was so glad to know that it held up to my memory. Thank you for this look at one of my early favorites.

I have the DelRey version, which has a cover that actually, shocker, depicts an event from the book. Read it a few times in the early 80’s, after having read the Pern books. It’s probably in Sturgeon’s 10%. The follow-on books were OK, but I never reread them.

“I have never been a Bob Dylan fan, and found the idea of him inspiring such a movement a bit preposterous.”

While I can understand not being a Dylan fan, I can’t see it as preposterous, since he pretty much did inspire such a movement in your own lifetime. He was the voice of the ’60s (And he totally deserved the Nobel).

What does surprise me is that McCaffrey, my father’s age, would appear to have been a Dylan fan!

I remember reading that Anne wrote the short story “The Ship Who Sang” after her father’s death as a way of dealing with her grief. Reading “Sang”, “Mourned”, and “Killed” as an arc about the process of grief and gaining perspective through the pain melds them together beautifully.

@@.-@ We’ll have to agree to disagree on the topic of Bob Dylan. :-)

@5 When re-reading, I was struck with the depth of emotions portrayed in the stories. I think as a young teenager, with little experience with death and loss, those aspects of the stories just went right over my head.

@1 It’s been a while since I read McCaffrey, but I remember that when I was reading (and rereading) her books that I concluded that the first books in any given series were the best, and the longer the series went on, the less I liked it.

There’s a minor caveat there in the Pern books in that there are subseries in there, so I tend to think of Dragnflight and Dragonsong both as “first books.”

These books will break your heart. Thom Christopher, who played Hawk in the tv series BUCK ROGERS and various awesome baddies in soaps, had a film option on this series in the mid-Eighties. It’s a pity he could never find backing.

So, if my heart is already broken from a real-life loss to that “far green country under a swift sunrise,” will I find these stories cathartic? Or unbearable? Can anyone speak to that?

It is hard to predict anyone’s individual reaction to any work of art, but in my case, I found the stories cathartic.

@9–I’d be hard-pressed to make that call for you. Grief is a different thing for everyone, and I am sorry for your loss. For what it’s worth, the stories never minimize Helva’s grief, she is 100% allowed to feel her pain and hate everything and be rude to her passengers/brawns, and eventually to move on. They’re also honest about the fact that the world moves on while someone grieves, and sometimes that’s a comfort, and sometimes it’s rage-inducing.

Anne McCaffrey wrote one other story about Helva, “The Ship Who Returned” – it was published in Robert Silverberg’s anthology “Far Horizons”. It picks up 78 years later, and Helva is struggling to deal with the loss of Niall.

Without digging up my copy to check, as I recall…

When I first read it I bought into the basic premise uncritically. Years later rereading it I was struck by the rather nasty slavery aspects of it, or as Granny Weatherwax says, “treating people as things.”

Children are born with severe medical conditions that preclude anything like a normal life, and require extremely expensive treatment. As the price of this treatment, their families are required to give them up completely. We never hear anything about Helva’s family, or the family of any of the other brainships. The paradigm seems to be that your child died for all practical purposes and you are supposed to mourn them and move on. WTF? How much of this was story contrivance, versus a reflection of the times, when frequently disabled people did end up in state hospitals where they were forgotten by everyone except for the staff?

And the cost issue, well, that brings us into the whole issue of who pays for health care, but probably best not to have that whole wrangle here.

Is this another case of “science fiction is really about the present”? Where the present is the economic and medical practices of the 1960s.

If this was written today, you’d really need to address why the shell people are channeled into a narrow range of professions, and why they are cut off not only from their family, but don’t seem to have any social life or contact except with other shell people and their medical and technical support staff.

Yes, there are shell person rights groups in the stories, but they are just trying to make sure the system is administered fairly and humanely, not questioning the fundamental assumptions of the system.

@captain Button at 13

What happened to the Brainship’s Family is one of the criticisms of the Helva stories. It’s fixed in the later stories with other ships. In PartnerShip, Nancia’s family and her relationship to them are a major part of her identity. In The Ship who Searched, Tia’s parents are characters in the beginning when she is young and later when she is older she communicates with them regularly much like a 20 something that has moved to a new city on her first job. Family is even mentioned in the Ship who Won when Carialle paints a self portrait of a ship with blond hair because all 5 of her sisters are blonde.

They also expand on the jobs that shell person can take in The Ship who Searched, such as investor, special effects artist, and lawyer.

The indentured servitude angle of Brains transformation and service struck me right off. However it is clear that payoff is very possible to achieve in a reasonable amount of time.

On the family issue I’ve always assumed that Nancia’s father used his status and influence not only to challenge the rules but change them.

However it is clear that payoff is very possible to achieve in a reasonable amount of time.

I probably reread this a dozen times in high school, but that’s over thirty years ago, so my details are fuzzy. But my memory is that most Brains never paid off their debts, and were indentured their entire lives. Helva pays hers off but I thought that was a matter of surprisingly lucrative assignments, not the norm.

Helva paid off her debt with some shrewd investments she made with a shell person investor. She even started her own company employing shell people. The brains that never paid off their debt, bought improvements for their ship, where as Helva, had hers done because of contamination. I really loved these stories, still re read them occasionally, along with the Pern stories and Crystal Singer.

@17, It is definitely implied that some Shell people have priorities other than buyout. Like buying improvements for their ship. Tia, in The Ship That Searched, remarks that brains happy in their work would rather spend their money on other things than buyout. I don’t recall which ship remarks that with the laws to protect them and advocates assigned to defend each shell person they can’t be made to do anything they really don’t want to.

There is at least one more Helva story: Honeymoon is about Niall and Helva’s trip to Beta Corvi. It’s quite short so I suppose it might have been folded into later editions of The Ship Who Sang. I first found it in the 1977 anthology Get Off the Unicorn. (If you are a past or present McCaffrey enthusiast, you should give this anthology a try – for the story intros if nothing else.)

My “well-loved” copy of The Ship Who Sang is the Del Rey version with the cover on the far right above (5th printing 1978), from a boxed set with Restoree, Decision At Doona, and To Ride Pegasus. Ship was my favorite of hers (other than the Dragonbooks), but I haven’t re-read it in years. Perhaps it’s time.

Elinor Busby won a Hugo for Best Fanzine in 1960. Pat Lupoff won a Hugo for Best Fanzine in 1963. Anne McCaffrey’s 1968 Hugo for Weyr Search appears to be the first Hugo won by a woman in a fiction category.

I seem to remember Crystal Singer having elements about having to pay off debts. I guess it was something that McCaffrey was concerned about.

I’ve got both both Restore and Decision at Doona, not a boxed set. I like the first for having a non badass but also not helpless heroine.

@21: The financial motivation I remember the crystal singers having is the desire to afford as luxurious off-world vacation as they can, for as long as they can stay away from Ballybran without their symbiote killing them.

@15 princessroxanna, Restoree was also one of my faves, as demonstrated by the very worn state of my copy. I suspect Restoree may not have aged well and have been afraid to revisit it. The boxed set was a Christmas or birthday present when I was a tween or early teen.

To Ride Pegasus is a fixup novel of stories set in the now/near-future, mostly starring Daffyd ap Owen. They are (or at least became) the “past history” of the Tower and Hive books. The original (AFAIK) Rowan and Damia stories are in the Get Off the Unicorn anthology I mentioned above. Nowadays it’s interesting to compare with the novels to see how the story changed. When the novels originally came out I recall being fannishly incensed by what in retrospect were fairly minor changes from the stories.

I remember feeling very sad/disturbed for Helva and Jennan/Niall for not being able to ah, get physical with their loves. I didn’t want to read more of the series after that, but someone told me about how Tia came up with a body to move around in and so I read that one. I felt better after that.

I wrote a paper in my high school English class about the Campbellian hero’s journey arc of this novel.

@24, I wish I could reassure you about Restoree but I’m not particularly Woke, especially about old favorites. But the only thing that struck me as problematic was Sara’s surgical makeover and that’s necessary to the plot.

I absolutely loved this series of novels and its positive approach to cyborgs. Tia is my favorite, as a scholar.

I think it’s stated that most Brains are able to pay off their debts within ten years of service, but many choose not to, as their employers are mostly reasonable and just. As a comparison, most home solar systems take 15-20, so I’d say it’s a reasonable time frame. Also, becoming indentured for ship service isn’t the only (or most lucrative) thing Brains can choose, it’s just one of the most coveted options. It’s implied that there are significantly cheaper and more lucrative options available, but that would make the protagonist something like an accountant, and that doesn’t give the story McCaffrey wanted to tell (shrewd investment side stories notwithstanding.)

Helva has inspired at least two songs, one by Cecelia Eng: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=boZuPl2cRdQ and the other by Anne Prather: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IRN3Co1F8qE