Much has been written about the enormous importance of looking things up before you write about them so as to avoid ranking too high on the Dan Brown Scale of Did Not Do The Research—but there’s another side to this particular coin. As someone who spends a hell of a lot of time looking stuff up on the internet, I can affirm that it is, in fact, possible to do more research than you can actually use.

There are any number of methodologies for conducting research, but the one I generally end up following to start with, at least, is the Wiki rabbit hole. It’s ill-advised to rely on Wikipedia for all of your information, of course, but it’s a jumping-off point from which you can track down primary sources; it tells you what you need to look up next. It can also lead to some fairly bizarre search strings, and you can come out miles away from where you started, having lost hours, but it’s fun most of the time…except for when it’s frustrating. It is also possible to go too deep, to get hung up on some particular tiny detail that almost certainly isn’t important enough to warrant this level of focus, and find yourself bogged down and going nowhere. There’s a point where you have to pause and back away: you don’t need to get a degree in the subject, you just need to not get specific things hilariously wrong.

Such as physical setting. The original draft of what would become my novel Strange Practice was written before Google Street View existed, and much-younger me hadn’t bothered to look up maps of London in the middle of NaNoWriMo rush, so there were several instances of completely erroneous geography worth at least 7 Dan Browns. When I rewrote it a decade later, I was able to accurately describe the setting and the routes characters would have taken through the city, including the sewers—although I then had to take a lot of those details out again because they did not need to be on the page.

This is the other consideration, with research: how much of what you now know do you need to tell your reader? For Strange Practice I spent a lot of time on urban exploration websites (I do this anyway, so it was fun to put that interest to use) including those devoted to clandestine sewer and drain exploration, and with that and the aid of a gorgeous 1930s London County Council Main Drainage map which I found on Google Image Search, I was able to pick out and describe a pathway through the sewers from point A to point B. Which was accurate and correct, but it also resulted in half a page of highly specific infodump about the Fleet sewer and its overflows, and—quite rightly—my editor told me to take it out again. All that needed to be there was the fact that this character had entered the sewer and made their way through it toward their destination before being apprehended. I could—and probably should—know the specific path they had taken, or at least that it was possible to take that path, but the reader didn’t need to know those minute details.

I don’t consider the time I spent plotting out the directions wasted, because I enjoyed myself immensely and it added a lot to my overall knowledge of London; that definitely gave me more confidence and security in my ability to write about a place I haven’t been to since 2005. It wasn’t too much research; it simply didn’t all need to be there at that point in the text.

This is a difficult line on which to balance; on the one hand, if you don’t add specific details to a scene you run the risk of looking like you don’t know what you’re talking about, and on the other if you do what I did and gleefully infodump all the stuff you’ve just learned onto the page, your reader is likely to feel lectured rather than told a story. It gets easier with practice. I recently wrote a novella about air crash investigation and practical necromancy, in which I had to learn a great deal about how air traffic control works, how flights are routed, how to read various types of chart, where various controls are located in the Boeing 737’s cockpit, and so on—and then I had to not have my protagonist lecture the audience about any of these things, or bring them up in conversation with the other characters unnecessarily. Writing a particularly intense scene where I had to walk that thin line felt physically exhausting, like lifting weights with my brain, but it was also deeply satisfying to have done.

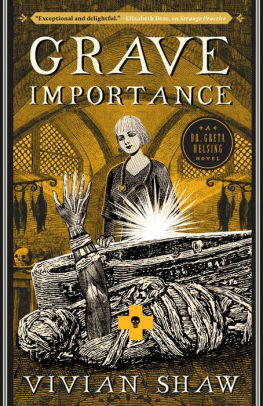

Buy the Book

Grave Importance

It’s worth pointing out that I could do it because it is so absurdly easy to get hold of useful resources online these days—which does increase the likelihood of getting hung up on one specific point and losing momentum, but it’s still so much fun. You can explore the 737 from stem to stern on The Boeing 737 Technical Site, or go play in SkyVector to create custom flight plans and roll around happily in all the different types of charts. Complete accident reports are easily accessible on the National Transportation Safety Board’s website. And it’s not just aviation-related resources; you can find almost anything on the internet if you keep looking. For a horror story set on Venus I could stuff my head full of Soviet Venera lander technical details at Don P. Mitchell’s site, complete with color photos of the planet’s surface, and listen to the lost-cosmonaut hoax recordings at (where else) lostcosmonauts.com. For Dreadful Company I didn’t have to rely on a twenty-year-old memory of a single and limited tour of the Palais Garnier to describe the interior; I was able to explore the whole of it from 3,794 miles away, because they have Google-Street-Viewed the inside of the building like they did with the British Museum, all the way from the lake in the cellars to Apollo’s lyre on the roof, and incidentally I just looked up the distance from Baltimore to Paris and got an answer in a fraction of a second. Research is easy if you have internet access, and there is no excuse for not doing it—but, having done it, care must be taken in what one does with it.

I think in the end it comes down to letting your story decide how much detail you need to include, based on the characters and their setting. Would the characters have a conversation explaining to each other (and therefore the audience) this information, or would it be casually alluded to without tons of detail? How would people who are familiar with the subject talk or think about it? What does the plot need in terms of this information; how necessary is it to put on the page?

It is also important to remember that you can spend time looking things up in extreme detail just because you’re interested in them, rather than for a specific story. Research is for writing but research is also for fun, and it is never a bad idea to add to your store of knowledge.

Now go explore the Paris Opera House and the British Museum for free.

Photo by Latemplanza (Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Vivian Shaw wears too many earrings and likes edged weapons and expensive ink. Her debut trilogy starring Dr. Greta Helsing is published by Orbit; her short fiction has featured in Uncanny and is forthcoming in Pseudopod. She is a stickler for research and currently lives in Baltimore with her wife, the author Arkady Martine. Look for Strange Practice and Dreadful Company now out, and Grave Importance coming in late summer 2019.

How much research do you need to do? Um… just enough?

I adore research. In fact I’d much rather research than write. You see the problem.

As much as possible, I guess?

@2: Alas, I’m with you.

Yes, absolutely. Even if the details and information you uncover aren’t in what you write, readers will pick up on your confidence & knowledge in what you do give them. Plus avoiding thuds and blunders helps build reader immersion. :-)

Research is an iceburg. A research the reader doesn’t see makes what they do see float properly.

The trick is to get a strong structure of general information so that you will know how much more specific info you’ll need. Some writers suggest that you find a good children’s book on the subject as your starting point. For minor details that won’t change your novel, leave an asterisk or some other marker and a note to look up the small point and keep moving with your writing so the research won’t stop your writing rhythm.

As an ancient person, I also suggest that you young’uns go to the physical library when you are researching because you will find peripheral information you didn’t know to look for. I went to research wild flowers in South America for a romantic adventure I was writing about ethnobotanists, and on the same shelf I came across a book on Southerners fleeing the US after the Civil War and settling in Brazil. That info changed the whole basis for my novel.

@5, Yes indeed, serendipity is a wonderful thing. And while the internet is a fine resource Real Books have their own advantages in terms of detail and the unexpected.

How much research? Echoing, “just enough,” unless you’d rather be researcher than writer.

Research is fun, and expands your mind. But the reader should never see more of it than a mariner sees of an iceberg; while the entire narrative is informed (and improved) by detailed research, no more than 10% of your research should show up on the page. I have been obsessed with Titan lately, and find that odd moon, and its composition and climate, fascinating. And have to fight the urge to put too many facts into my narrative.

Although there is a certain subset of military SF fandom that seems to love the infodump, and can’t get enough of calibers and guidance systems and closing velocities and radar returns, etc, etc.

So there’s a few layers here.

There’s the underlying basics you always need to do, so that you don’t fill the car up with olive oil or go shopping in the wrong currency or electrify the macerations.

There’s the stuff that needs to be done to make your plot work which the reader doesn’t need to know, like for example in The Martian, Andy Weir worked out exactly when his mission started and ended because he needed to know the orbital mechanics and the days involved. We as readers needed some scientist characters uttering technobabble and a chapter heading with a timestamp.

And then there’s the stuff you need to know that we as readers *also* need to know for the plot to work. Especially when general knowledge turns out to be wrong, which is surprisingly often. Like for example how long you can spend in space without a suit before you die (around 90 sec, though you’ll almost certainly pass out after 15-20). Or how exactly to build a fire or keep yourself alive in a survival situation.

Rafael Sabatini, author of such classic swashbucklers as The Sea Hawk, Captain Blood and Scaramouche, opined somewhere that to write a good historical novel you must learn enough about the period to write an entire non-fiction book about it. As a statement of a general principle, I’d call that an exaggeration. But his point is still well taken. A good fiction writer will inevitably learn far more about a topic of research than ever could, of should, make it on to the page. The “extra” information is still necessary to keep those details that do surface informed and consistent. The challenge of disclosing research is deciding which 99% to leave out.

@5&6 I agree. The internet is great, but books remain as indispensable as ever. Where else can you hope to find the vital information you didn’t know you were looking for?

@10 Given the magnificent results Sabatini produced, I would easily believe he put that level of work into the books.

One modern naval adventure writer I follow, Julian Stockwin, visits all the places portrayed in his books, visits museums, and works with local historians. Sounds like a dream job to me!

And I have to wait until September to find out who is going into the sewer and why?!

One thing worth remembering is that if you’re doing a review of an older work, it used to be much, much harder to do this sort of research. I was recently reading a deconstruction of a book first published in 1979, and the person doing the writing, and the commenters, were complaining about “bad research” using the fact that they could easily find information online, get scans of historical diaries, or search for and order appropriate books on Amazon, as evidence that this was easy.

They were talking about historical research on daily women’s work in US frontier communities in the mid-1800s.

In the early 1990s, I studied under a woman who got her PhD, in the early 1980s, doing the exact sort of research they were saying that a fiction writer in the 1970s ought to have found “easy.” It wasn’t easy, at all, at that time, as women’s daily writings had largely been ignored before second-wave feminists started doing academic history, there was no easy way to search the catalogs of libraries you weren’t physically able to visit, etc.

At the local public library, you couldn’t even search the catalog of other branches within your regional library system.

Research these days is so easy, that one can forget that the “easy” research done online is only possible because of vasts amount of extraordinarily difficult research done by others in the past, and also vast amounts of work taking resources that were only available on paper in a single location, and working to put it online.

@11 While I share your admiration of Rafael Sabatini, his own work has been criticized for anachronisms–in his descriptions of sailing ships, for example, and his use of fencing terminology. Perhaps he was taking liberties rather than making errors. In either case, I don’t much care. It never detracted from the pleasure I received from his novels.

How much research do you need to do? As much as you want, but 99% of your readers won’t care and the remaining 1% will tear you down over any errors or dramatic liberty anyway. Just go with what general society knows about your subject, and you’ll be fine.

Something we haven’t mentioned, but should is that after all that research goes on the page, we should ask an expert to read what we have written to check for errors. It need not be the whole manuscript, only specific scenes. Experts are pretty dang easy to find these days, and some love to give imput.

I believe that the historical and children’s novelist Rosemary Sutcliff once commented that if you imagine the time it takes you to write your book as a year, then three months should be research and nine the writing, re-writing etc.

It’s good to read enough to spot if one source has serious errors. I read several books about miscegenation and passing a couple of years back, and one of them assumed that the “one drop rule” for classifying people as black had always been the rule. It was a 20th century thing, and I’d read enough other stuff by that point to know the book was wrong.

I am reminded of a certain Neolithic fiction series where pages of exposition alternated with pages of infodump. I suppose it was interesting, even so, but it definiitely pulled me out of my immersion in the story.

@19 Don’t keep us in suspense. Name names! :-)

John Sanford and Ctein’s book ‘Saturn Run’ has a great afterword where they explain how the propulsion parameters and orbital mechanics of the US and Chinese spacecrafts voyages were worked out on a computer. A good read.