In this biweekly series, we’re exploring the evolution of both major and minor figures in Tolkien’s legendarium, tracing the transformations of these characters through drafts and early manuscripts through to the finished work. This week’s installment focuses on Glorfindel, an Elf-lord with only a few appearances, who channels the divine power of the Other-world and whose presence in Middle-earth twice assures the survival of—well, basically everything.

Glorfindel has the double distinction of being, first of all, an elf whose name was so unique that Tolkien felt like it couldn’t be used again for anyone else; and second of all, an elf whose power was so great that he was specifically sent back to Middle-earth by the Valar to aid Elrond and Gandalf in the fight against Sauron. But his fame doesn’t end there: the tale of this particular character is also what drove Tolkien to almost tirelessly revise his theory of elvish reincarnation.

His textual history, while not as complex as some of the others’ we’ve looked at so far in this series, is particularly fascinating because he appeared in a relatively stable form so early in Tolkien’s drafts. In fact, the Glorfindel who appears in the 1916 or 1917 version of The Fall of Gondolin is not all that different from the Glorfindel of the final version of The Lord of the Rings—and indeed, the latter depends entirely on the former for its coherence.

The earliest drafts of The Fall of Gondolin were written during and around Tolkien’s time in the trenches of WWI, though as Christopher Tolkien notes, it’s difficult to date them exactly since Tolkien himself offered several different origins stories for the (The Fall of Gondolin, hereafter FoG, 21-22). Whatever the exact date of the story’s birth, it is at least clear that Tolkien was approximately 24 years old when he began to pen these drafts, and that they represented, significantly, the first forays into the great mythos growing in his mind.

However much one loves Tolkien and admires his work, it must be admitted that these early drafts are difficult to read. Here’s the sentence that introduces the star of today’s column: “There stood the house of the Golden Flower who bare a rayed sun upon their shield, and their chief Glorfindel bare a mantel so broidered in threads of gold that it was diapered with celandine as a field in spring; and his arms were damascened with cunning gold” (Book of Lost Tales II, hereafter BLT II, 174-5). The vocabulary is rich and beautiful, to be sure, but it leaves us with a text that is difficult to navigate, especially if you aren’t used to language of that sort.

The important thing to note is that even here in the early stages, we have Glorfindel, Lord of the House of the Golden Flower of Gondolin, as powerful and high-hearted as he is beautiful. When Gondolin is sacked by the armies of Morgoth and overrun with Balrogs (seriously—Our Heroes kill them by the dozen in the early days), Glorfindel and his company act as rear-guard for the fleeing refugees, and it’s the selfless sacrifice of Glorfindel that allows them to escape when a Balrog comes roaring into their midst. Without the scene of the Battle of the Cleft of Eagles, in fact, Glorfindel as he is known in The Lord of the Rings could not exist.

The point is that in The Lord of the Rings, Glorfindel acts as a shaman, which essentially means that he is a sort of in-between figure who has direct access to both the spiritual and physical worlds, and that his purpose on Middle-earth is to protect “souls” who are threatened by the powers of the Shadow. He couldn’t do this if it weren’t for his previous battle with the Balrog. Why? Because that battle is his initiation.

There are a number of elements that seem to be ubiquitous in a shamanic initiation experience: a dangerous or narrow passage, a dizzying climb, the clash of opposites, an encounter with fire, the experience of radical paradoxes, a struggle with a demonic force, and the ascent of the soul, often symbolized by the appearance of eagles. All of these things are present even in the earliest versions of Glorfindel’s battle with the Balrog. Let’s take a closer look.

First of all, the fact that the battle takes place above the “Cleft of Eagles” already signals that we’re going to be dealing with some kind of ecstasy or spiritual transfiguration. Eagles, in many mythologies and in Tolkien’s stories, metaphorically represent the moment when the struggling soul is transformed and raised up by some great act of courage, sacrifice, or heroism. (This is, incidentally, why the Fellowship couldn’t possibly just fly the eagles to Mordor. The eagles only ever appear when the soul has extended itself to the utmost, poured itself out, or reached the point at which there is no more physical escape: suddenly, in agony and ecstasy, the soul is transfigured and raised beyond the heights of the material world. So no, just sitting around waiting on the eagles to function as literal transportation across Middle-earth doesn’t work, won’t ever work. Go ahead. Look at all the scenes with eagles. I’ll wait.) So, when the refugees of Gondolin enter the Cleft of Eagles, with enemies on their heels and a Balrog leaping down among them, we should be prepared for an encounter that will try the soul.

And it does. The path the company travels is one that hems them in: the Cleft of Eagles, or Cirith Thoronath—

…is an ill place by reason of its height, for this is so great that spring nor summer come ever there, and it is very cold. […] The path is narrow, and of the right or westerly hand a sheer wall rises nigh seven chains from the way, ere it bursts atop into jagged pinnacles where are many eyries. […] But of the other hand is a fall not right sheer yet dreadly steep, and it has long teeth of rock up-pointing so that one may climb down—or fall maybe—but by no means up. And from that deep is no escape at either end any more than by the sides. (FoG 104)

In this description we see some of the important markers for a shamanic initiation. The way is dangerous and narrow, there are great opposites existing simultaneously (on the one hand is a great height and on the other a great depth), and it’s terribly cold, which will be important later because the Balrog comes as a demon of fire (heat).

Then the Balrog itself arrives. We read then that “Glorfindel leapt forward upon him and his golden armour gleamed strangely in the moon, and he hewed at that demon […]. Now there was a deadly combat upon that high rock above the folk” (FoG 107). They climb higher and higher locked in combat—another important marker of shamanic initiation. Glorfindel deals a mortal blow to his demonic enemy, but as the Balrog falls, he clutches Glorfindel’s hair beneath his helm and together they fall to their deaths (FoG 108). Later, in the published Silmarillion, we’re just told that “both fell to ruin in the abyss” (243), which foreshadows Gandalf’s later encounter with a Balrog. Personally, I prefer the version in The Silmarillion, because it seems too cruel that the feature for which Glorfindel received his unique name—his golden hair—should be his downfall.

Regardless of how he dies, Glorfindel’s body is retrieved by the Lord of the Eagles, Thorondor, from the depths of the abyss: metaphorically speaking, Glorfindel’s spiritual battle against a demon leads to the transfiguration of his soul. Thorondor also buries the body in a high grave, “and a green turf came there, and yellow flowers bloomed upon it amid the barrenness of stone, until the world was changed” (Sil 243). (In the early draft of The Fall of Gondolin, Tuor has Glorfindel buried in a cairn, but Thorondor protects it ever after.)

Buy the Book

Silver in the Wood

What happened to Glorfindel, and how did he return? In a very late essay, presented roughly in two parts (as a sort of note, and then as a more complete, though still unfinished draft), Tolkien expounds upon Glorfindel’s role in the text. An “air of special power and sanctity […] surrounds” him in The Lord of the Rings because of his death and reincarnation, Tolkien explains. In fact, through his sojourn in Valinor, between death and “resurrection,” the elf lord actually “regained the primitive innocence and grace of the Eldar,” such that he had become “almost an equal” of the Maiar and a particular friend of Olórin, a.k.a. pre-Middle-earth Gandalf (Peoples of Middle-earth, hereafter PM, 381).

This claim is particularly significant because Glorfindel, as a follower of Turgon and a lord of Gondolin, was a leading participant in the rebellion of the Noldor against the Valar; his return to “primitive innocence and grace” is a therefore return to a sort of pre-fall state, a hallmark of the shamanic initiation. His rise to a level of power that rivaled that of a Maia (Gandalf, Sauron, and Balrogs are all Maiar) emphasizes the fact that Glorfindel is very much of two worlds at once. Within his person the spiritual and the material take up residence. He straddles the divisions between worlds: between Valinor and Middle-earth, the seen and the unseen. And, as a spiritual warrior and shaman he is particularly selected to return to Middle-earth to aid Elrond in the war against the growing Shadow (PM 384).

Now, what does his early experience with the Balrog have to do with his appearance in The Lord of the Rings? As I said before, the latter cannot exist without the former. In The Lord of the Rings, Glorfindel specifically plays the role of spiritual guide and protector against the demonic power of the Nazgûl. In “The Flight to the Ford,” Glorfindel is situated in three places in particular: the Road, the Bridge, and the Ford, all three of which are important because they represent spaces that are in between the spiritual and the material (and they often show up as symbols in shamanic rituals). The Elf-lord acts as a protector on the Road, but he also leaves his token on the Bridge which signals to Aragorn that it’s safe for them to cross (I, xii, 210). His white horse, Asfaloth (another marker of the shaman), escorts Frodo across the dangerous passage of the Ford.1 Without that initial encounter with the Balrog, his subsequent transfiguration, and his recovery in Valinor, Glorfindel would be entirely incapable of helping Frodo and facing the Nazgûl, the evil shamans.2

Gandalf explains all this to Frodo as he lies in Rivendell, recovering. “‘I thought I saw a white figure that shone and did not grow dim like the others,’” Frodo says. “‘Was that Glorfindel then?’” (II, i, 223). Gandalf’s answer comes in two parts, one before Frodo even asks the question. First, he explains that “‘here in Rivendell there live still some of [Sauron’s] chief foes: the Elven-wise, lords of the Eldar from beyond the furthest seas. They do not fear the Ringwraiths, for those who have dwelt in the Blessed Realm live at one in both worlds, and against both the Seen and the Unseen they have great power’” (I, i, 222-223). Valinor is situated in relation to Middle-earth as a version of Elven paradise, and therefore Gandalf’s comment emphasizes the spiritual divide that these figures, the Elven-wise, bridge; they have a foot in both worlds, as it were, and thus they are able to channel their divine power to bring endangered souls to safety; i.e., to act as shamans.

The second part of Gandalf’s answer focuses more specifically on Glorfindel. “‘Yes,’” he reassures Frodo, “‘you saw him for a moment as he is upon the other side: one of the mighty of the Firstborn. He is an Elf-lord of a house of princes. Indeed there is a power in Rivendell to withstand the might of Mordor, for a while’” (II, i, 223). With these comments Gandalf confirms Frodo’s suspicions, that the “shining figure of white light” was indeed Glorfindel unveiling himself against those evil shamans, the Nazgûl: and “caught between fire and water, and seeing an Elf-lord revealed in his wrath, they were dismayed, and their horses were stricken with madness” (II, i, 224). Again, elements are put in opposition: fire and water, much like the fierce cold and fire of the battle above the Cleft of Eagles. That it is Glorfindel who initiates this dichotomic situation is reflective of the elf’s status as shaman and spiritual intercessor, “for [he] knew that a flood would come down, if the Riders tried to cross, and then he would have to deal with any that were left on his side of the river” (II, i, 224). Glorfindel thus overcomes the Nazgûl by forcing them into the liminal space between opposites; unlike the Elf-lord, the Nazgûl are not able to transcend the difference, are stripped of their corporeality, and left to return “unhorsed” to Sauron—and given the extent to which shamans depend on their equine partners, the defeat is a great one indeed despite the fact that “the Ringwraiths themselves cannot be so easily destroyed” (II, i, 224).

Glorfindel is thus a key figure in the tales of Middle-earth despite the relatively limited role he at first appears to play. First, his sacrifice in the Cirith Thoronath makes it possible for the refugees of Gondolin to escape, thereby ensuring the survival of the young Eärendil (who later also becomes a shamanic intercessor) and, by extension, Elrond and Elros. Thus, because of Glorfindel we have one of the last strongholds in the war against Sauron (Elrond’s Imladris) and the line which produced Aragorn (Elros’s Númenoreans), the returning king of Gondor and Arnor. Then, in The Lord of the Rings, Glorfindel reprises his role as a shamanic intercessor and protector, one of the few who, because of his spiritual transfiguration, was able both to ride openly against the Nine and to provide Frodo with safe-passage over the Ford and into the safe haven of Rivendell. Without Glorfindel, the Ring never would have made it as far as Rivendell.

Glorfindel fascinates me because he represents one of those figures that so captured Tolkien’s imagination, a person Tolkien saw with such clarity that he was allowed to exist in nearly the same form from the earliest days to the latest. And not only that, but the whole trajectory of his character leads up to that miraculous encounter at the Ford of Bruinen. Glorfindel is a particularly significant character because his appearance in The Lord of the Rings proves that the spiritual world is not removed from the material: we just have to know how and where to look for it. Glorfindel’s miraculous appearance on the Road at just the right moment, his past which perfectly prepared him for the flight to the Ford, his nearly instinctive self-sacrifice—all these point to the fact that the Powers have not abandoned Middle-earth, nor are they as far away as they might at times seem. Glorfindel, along with Gandalf and others, reveal to readers, as well as to the characters around them, that the Valar (and by extension, Ilúvatar) are working for the good always, even when they themselves appear to be absent or deaf to the world’s groaning.

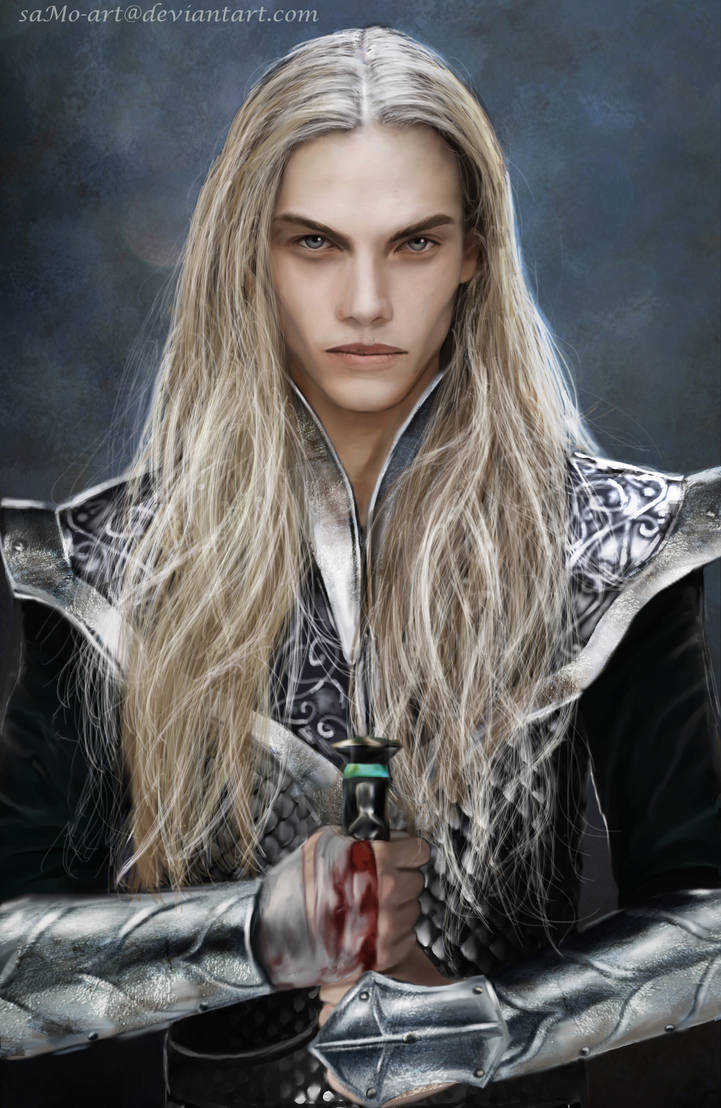

Top image: Glorfindel, by SaMo-art.

Megan N. Fontenot is a hopelessly infatuated Tolkien fan and scholar who is very happy that this week’s star didn’t have a special character in his name. Catch her on Twitter @MeganNFontenot1 for scholarly and unscholarly news and other sometimes-tragic tales.

[1]No eagles appear in this moment, but, significantly, Asfaloth himself is connected to birds through metaphors and similes of flight. The narrator says that Asfaloth “sped like the wind,” and again, the horse and rider pass “like a flash of white fire, the elf-horse speeding as if on wings” (I, xii, 213). Glorfindel first sends the horse off with the command “‘Fly!’” (I, xii, 212). In this case, the horse is the vehicle of the soul's escape and is a symbolic stand-in for the eagles.

[2]This explains my frustration over and rejection of Arwen’s appearance in Glorfindel’s place in Peter Jackson’s film adaption. Arwen could not possibly have faced the Nazgûl (even supposing that Elrond would have allowed her to leave Rivendell during such a dangerous time, which, given his tendency to keep her sequestered away, seems unlikely). Though likely powerful in her own right, she was not a shaman. She had not “dwelt in the Blessed Realm” and did not “live at once in both worlds” (II, i, 223). As Glorfindel explains, “‘[t]here are few even in Rivendell that can ride openly against the Nine’” (I, xii, 210). Arwen was not one of these. Indeed, if anything, Arwen’s brief and almost nonexistent role in The Lord of the Rings rather serves to emphasize the extent to which the Elves have declined since the days of her counterpart Lúthien: where Lúthien is able to face even Morgoth and challenge him with her power, and indeed to break the foundations of Sauron’s stronghold and send his naked spirit “quaking back to Morgoth” (S 175), Arwen vacillates between two safe havens, Rivendell and Lothlórien.

I really love this series. There is so much depth in so many characters

Gandalf facing the Balrog at the Bridge: “%#$%, I _should_ have brought Glorfindel.”

“for [he] knew that a flood would come down”

The flood was commanded by Elrond, who has not been to Valinor yet. So I’m not sure that there’s any intercession with the divine involved in that.

Ironically–and if I had more space I would’ve mentioned this in the article–Glorfindel was part of the Fellowship in the very beginning, but Tolkien almost immediately took him out! Then it became Gandalf and like 5 hobbits, if you can imagine that…

Luckily for me I am used to language like ‘diapered with celandine’ thanks to Walter Scott and E.R. Eddison.

When in one of The Hobbit movies we see the Eagles leave the expedition on top of a really high rock in the middle of a plain, my sister said, “So that’s why the Eagles didn’t fly the ring to Mordor: they’re kind of jerks.”

Very cool essay, thanks for it.

Jeff Daniel’s line in The Martian – “If we are going to have a secret project called “Elrond”, then I want my code name to be ‘Glorfindel'” makes much more sense after reading the above article. Teddy is clearly a Tolkien super-fan and understands in an instant the important background role played by the big G leading up to Elrond’s Council. He wants to play the same type of big behind the scene role in Mark’s rescue. Brilliant.

Wow, this is awesome. I must admit I never paid too much attention to Glorfindel. As for his exclusion from the movie, I do understand it – it definitely is cutting out a lot of thematic awesomeness, but it’s the kind of thing that in a movie would have required a lot more setup, and movies, I think, need a litlte more economy of storytelling than a book.

That said, this is sooooooo good :) Do you think Tolkien would have been familiar with the shamanic connections – my knowledge is mostly in our shared Catholcisim which doesn’t quite have the same concept of ‘shamans’ (although some of the symbolism/concepts exists in other ways). But, I know he was also interested in a lot of Norse/northern mythologies, so I’m wondering if that same type of symbolism exists there.

That said, I really love your symbolism of the eagles and what it represents in terms of spiritual transformation (ecstacy and agony reminds me very much of Bernini’s statue of The Ecstacy of St. Teresa), and how they are only sent once the soul is at its limit – which is in line with, I think, Tolkien’s ideas on grace and his words about the ending of LotR where Frodo gives everything he can and it’s still not enough (but it still works out).

@@.-@: elrond is descended from earendil amd elwing, thus he is by nature divine, having a maia for a great–grandma.

Yes, but by that argument so is Arwen…just a couple more generations removed!

Love to see Glorfindel getting some love, but the parameters set by Tolkien and used as evidence here do not actually support your argument that Glorfindel’s ability to face the Nazgul is contingent upon his earlier actions during the Fall of Gondolin. He is a prince of the Noldor who had seen the light of the trees, with or without reincarnation, and Galadriel, Gil-Galad, Fingolfin, Turgon, Feanor, or any host of others could well have fit the bill (only one still being alive at the time, of course).

@12, Gildor is still around. “Gildor Inglorion of the House of Finrod. We are Exiles…” remember? And the Rider drew off as his band approached.

in general I agree with you, I just couldn’t figure how to say so politely. My brain keeps short-circuiting on the shaman-stuff vs Tolkien’s known devout Catholicism.

I also tend to take more seriously thiings contemporary or prior to the writing of LOTR more than the efforts to make everything fit better after it. But that’s just me, and mosty comes up with Galadriel. An dthe fate of Elrond’s kids..

I suppose Arwen could have been like her foremother, just never had motiviation. Luthien doesn’t seem to have done much until her parents provided motivation. Then, as we know, she did a great deal. But Arwen loves her father and he’s not forbidden her marriage nor set an impossible task for her hand, nor locked her up. She has no reason not to cooperate with him and if she’s looking at never seeing him again once she’s wed and dead, I can conceive of her as wanting that parting to be on good terms. I have strong suspicions that Luthien did not care much for her family after the shenanigans, since the wedded couple don’t settle in Doriath.

I would also add that while Arwen (although the daughter of one of the most powerful elves remaining in Middle-Earth and the granddaughter of one of the other most powerful) is almost certainly not the equal of Luthien, the Nazgul even together are far from being equals to Morgoth or even Sauron. And they are further diminished because of Sauron’s loss of the One Ring.

Glorfindel was one of the characters who gave LotR depth for me. Even before I knew the Gondolin story, it was obvious that there was much, much more to him than the couple of glimpses we got in the books.

@6: Yep, “diapered with celandine as a field in spring; and his arms were damascened with cunning gold” is straight outta Zimizmvia.

Gil-galad was born in Middle-Earth; he didn’t see the Trees or hang with the Ainur.

Tolkien Gateway says Tolkien just re-used a name for LotR; the “became almost like a Maia” is from writings in the last year of his life. You can view it as canon, but at the time of writing LotR, it seems more that his power was rooted simply in being a Noldo from Valinor, like Galadriel and presumably Gildor.

> we see the Eagles leave the expedition on top of a really high rock in the middle of a plain

IIRC in the book Gandalf asks to be dropped at the Carrock, a high rock by the Anduin and near Beorn.

Nice article! Some have mentioned the trouble with using the label ‘shaman’ when Tolkien was was devout Catholic. I think the purpose of using the term ‘shaman’ is to outline the characteristics of certain players in the legend possess. One could easily use ‘angel’ or ‘saint’ instead, but I think the connotation of ‘shaman’ fits better, as the connotations of angel or saint offer a different set of characteristics and tone.

@@.-@: YES. Glorfindel does cause commotion and fear among the Nazgul, but it is Elrond who has power over the river. So Arwen’s role in that scene is not random: she is, after all, Elrond’s daughter.

@10: That, too. And, as Half-Elven, their whole family is unique, having the privilege of choosing whether to become elves or human.

This is a nice article (thanks, Ms. Fontenot!), but it does extrapolate too much.

You make some interesting points in your article about the relationship between physical and spiritual in Tolkien’s writing. However time and again Tolkein refuted any suggestion that he was writing an allegory. The possible exception is the scouring of the shire. If Tolkein were writing a spiritual allegory, as others have mentioned, his strongly Catholic faith would have driven a Christian spiritual allegory rather than a new age one. I doubt that in his time and his experience he would have even heard of Shamanism.

Sometimes it’s too easy to read our own beliefs back into someone else’s work but we should be careful not to ignore what is clearly known about their personal beliefs and stated aims.

Having said all that authors do to some extent surrender their work to the reader’s interpretation and Tolkein more than most provides rich fruit to allegorise. As long as we acknowledge that they are ours not his.

I am not sure you understand what Tolkien was saying when he said he wasn’t writing an allegory. He said that he wasn’t writing an allegory about actual events or people like the war, or Jesus, etc.

However he was always clear that he was writing a story imbued with what he saw as ‘Truths’ on a spiritual level. He’s on record as stating that the end (where Frodo is unable to destroy the Ring, but it is destroyed to his previous mercy to Gollum) is a meditation on the Lord’s Prayer and the concepts of mercy/grace. While the concept of shamanism doesn’t exist in Catholicism, there are some parallel concepts. There may also be some things he was drawing on from other mythologies as he and his contemporaries were very interested in those types of things and saw ‘Truth’ in those as well.

I don’t know if that is called ‘spiritual allegory’, but he clearly was being intentional about it.

Watching Fellowship of the Ring -Arwen rides Frodo to Rivendell rn (when I started this post) and missed Glorfindel more with the subtext covered here.

Understood replacing him w/Arwen even back when I first watched it in the cinema in December 2001 (wow nearly 20 years ago.)

But disappointed that Arwen’s awesome introduction in the movies wasn’t leading her to upgraded role later.

Missed opportunities all around. Seems pointless to start her off so strong n then fizzle out.

Looking back Glorfindel should have been in it.

For the uninitiated, it may be worth mentioning The aftermath of Nirnaeth Arnoediad was the battle that Glorfindel help to protect the (rear-guard) remnants of the retreating Gondolin army.

@21: Look at the bright side: at least she’s in it. Book Arwen is barely there. She only speaks in the Appendix –and only once.

Yeah, I really don’t mind Arwen getting Glorifindel’s part, because as a desdendent of Luthien I think it actually IS feasible that she could also have her own power.

Glorfindel seeing the Balrog coming towards the Fellowship: “Oh no, not again.”

As someone who has studied shamanism in considerable depth for a religions class at University, I find this article very intriguing. I never made the connection of Glorfindel to that of a shaman, and all the parallels within, but now that it’s been pointed out it makes considerable sense. So thank you for adding depth to an already pretty cool character. I look forward to future articles!

I will say I’m surprised at all the comments berating the author for discussing shamanism simply because Tolkien was a devout Catholic. Because apparently being a devout Catholic requires you only use Catholicism as inspiration for spiritual writings of fiction, or that as a well respected Professor at a famous University Tolkien definitely had zero exposure to shamanism as a concept. Even the notion that Catholicism, as a religion that was very successful in converting others, could not possibly have any similarity to shamanism in any way, a religion that not only predates but likely influenced some of Catholicism’s practices and traditions, either at origin or as a tool to convert, seems absurd.

“Book Arwen is barely there. She only speaks in the Appendix –and only once.”

Pretty sure she speaks in the main text, telling Frodo he can “take her place” on a ship west (not really how it works, but anyway.) Then in the Appendix she speaks to 20 year old Aragorn and dying Aragorn. Which may be more lines than Glorfindel has.

We know that Tolkien’s Catholicism did not preclude a certain amount of inspiration from other religions since the Valar are clearly and by Tolkien’s admission inspired by pagan gods, but Christianized by making them inferior created beings. Nor this his dislike of allegory rule it out, since that only meant that the entire story is not a retelling of another story in coded form, not that individual elements can not have real-world or mythological inspiration. So I don’t think he in principle would reject taking inspiration from shaman religions.

But I would wonder how much he was familiar with shaman religions. It would not be part of his education the way Norse or ancient Greek religion would be, and I don’t know whether he sought out information about them, or what quality of information would be available at this time.

@17, Well one could not use angel or saint instead, precisely because it does not invoke the same concepts. Angels don’t really have initiation ceremonies, which is a major part of the pattern the original poster sees. Saints have baptism, which is an initiation ceremony of sorts, but obviously quite a different one and not really an initiation to sainthood as such.

@27: Your memory is better than mine, and I have not read the books in a long while. And I think it is more lines than Glorfindel has in LOTR, since I only remember him screaming a battle cry of some sorts, and again I could be remembering it wrong.

But my point still stands –Arwen is barely in the books at all.

@27, @30: I’d say that Arwen feels less ‘present’ in the story not because of how few words she speaks but rather because she doesn’t really do or say anything particularly critical to the story while in POV focus during the main narrative. Glorfindel, in contrast, provides some crucial information in his few lines and is seen taking action at a critical juncture.

Yet while his actions do fit the shaman trope pretty well, I’ve long felt that the character is less important for the help he provided Frodo at that moment and more important as a foil for the nature of the Nazgûl. His appearance as seen from the wraith-world—not merely bright and powerful, but essentially unchanged while despair descends and the rest of the world fades into bleakness—illustrates the envy that many Men have felt about the Elves. It thus demonstrates the allure of what was offered to nine men by the titular Lord of the Rings, as well as the corruption entailed by accepting them (at least for those readers who understand how Melkor corrupted some Men’s understanding of Ilúvatar’s Gift).

I haven’t read HoME on the writing of LotR, but the Tor essay on Eowyn said she was originally Aragorn’s love interest. Arwen might feel tacked on because she was a late addition.

Also, while Luthien and by extension Melian are key parts of Tolkien’s life-long Great Tales, a lot of the *other* cool women of the Silmarillion (or stuff that didn’t make the Silmarillion) were apparently invented after LotR was published. So Tolkien may have been progressing toward more and more diverse women. As it is, Arwen is less interesting than Ioreth…

@31: Excellent points all! Even more so if we remember that Morgoth dispersed part of his essence into the very fabric of Middle Earth, tainting it forever with darkness, even after he was banished.

@32: Huh. I guess I’ll have to check out that essay. Eowyn is such a wonderful character (and Miranda Otto played her so well) that one feels she is a better match for Aragorn than wallflower Arwen.

Well, even in LOTR there’s Rosie, who is a wonderful character, and of course Eowyn. And cousin Lobelia! But, alas, I don’t even remember Ioreth…

@32 – I literally laughed out loud at the Ioreth comment. How can you not remember Ioreth??? She’s the wise woman who talks Aragorn’s ear off after the battle, lol.

Ian@31: she doesn’t really do or say anything particularly critical to the story while in POV focus during the main narrative [emphasis mine]

Glad you included that bit, because while out of view, she is creating a flag for Aragorn to use—a flag that (1) announces for the besieged Minas Tirith that the corsair ships sailing up the Anduin are actually allies rather than reinforcements for the enemy, AND (2) that the captain of the fleet, Aragorn, is the long-awaited Return of the King: “There flowered a White Tree, and that was for Gondor; but Seven Stars were about it, and a high crown above it, the signs of Elendil that no lord had borne for years beyond count. And the stars flamed in the sunlight, for they were wrought of gems by Arwen daughter of Elrond; and the crown was bright in the morning, for it was wrought of mithril and gold.”

@34: Still doesn’t ring a bell… :-D

@35: “Glad you included that bit, because while out of view, she is creating a flag for Aragorn to use…”

Yes, she is embroidering. FOR THREE WHOLE BOOKS. I guess she deserved a medal after all…

I’m actually fascinated by the fact that Arwen embroiders. A lot of Tolkien’s female (elvish) characters are ridiculously artistically talented, including Nerdanel (a sculptor), Miriel (a weaver and the inventor of embroidery!), Melian (a musician, architect, and weaver, though she isn’t properly elvish), Luthien (also a musician and something of a weaver)… So we might be tempted to brush off Arwen’s devotion to embroidery as somewhat sexist, but actually, she’s following in a long tradition of artistically inclined females who, significantly, tend to be generous, unselfish, and generally ethical with their art (especially when compared to people like Fëanor).

Plus, it’s embroidery with MITHRIL which is pretty sweet.

Really fascinating article, and an interesting perspective.

@36 There is also her gift and her advice to Frodo at the end of ROTK.

Have you read the tale of Aragorn and Arwen in the appendices?

@37 That is really interesting, especially when considered in light of Tolkien’s idea of subcreation.

@39: Yes, but the Appendices are outside of the main story, and there she also barely says or does anything. I loved that she takes Aragorn to task for giving up on life, though.

@37: That is a very illuminating observation (and what ladyrian said). Would you PLEASE write a complete essay on it?

I always appreciated that Glorfindel was in the service of Turgon, and when he returned to Middle Earth moved in with Turgon’s Grandson Elrond. He was still loyal to that line, despite being mightier than Elrond himself.

My first Shadowrun character (1st Ed, I’m old) was an Elven Rigger. I named him Glorfindel, and decided he hated it because his parents were weirdo hippy types so he went by Fin.

Really interesting article. I was hoping to see some mention of the fact that it was Glorfindal that drove the Witch King out of Angmar and spoke the prophesy that he would not be killed by a man.