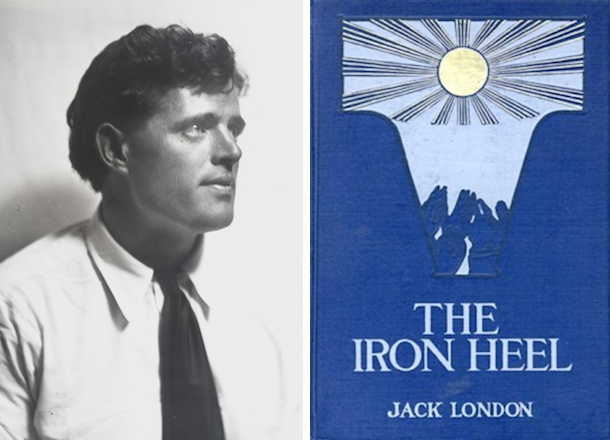

My first encounter with Jack London’s work was the short story “To Build a Fire,” in which the protagonist attempts to survive the elements and keep wolves at bay in the wilderness by keeping a fire going while also fighting off exhaustion. Then, after encountering the novels The Call of the Wild and White Fang, I figured that all of London’s work was populated with outdoorsy men who either befriend or fight wolves. So it was a surprise to learn that he had also written a dystopian novel: The Iron Heel.

Pessimistic in tone and ironic in structure, proposing a world that is overrun by greed and where the wealthy Oligarchy use their influence to enslave the majority of the population of Earth, the novel is a stark contrast to the tone and content of much of London’s more well-known work. Published in 1908, The Iron Heel seems to predict some of the defining difficulties of the twentieth century, such as the first World War and the Great Depression. It also prefigures some of the paradigmatic dystopian novels that would come in the following half century such as 1984, Brave New World, and We, by the Russian novelist Yevgeny Zamyatin. In writing The Iron Heel, London created a template that other dystopian novels will follow and helped to define the genre.

The plot of the novel is rather simple, but the structure is complex and lends greater weight to the story. The novel opens with a fictional foreword written by Anthony Meredith, a historian writing in the year 419 B.O.M. (era of the Brotherhood of Man), in which he describes a found document: the Everhard Manuscript. The manuscript, written by Avis Everhard, describes her first encounters with Ernest Everhard, a labor leader and socialist intellectual, through their eventual courtship and marriage. During their courtship, Ernest speaks to a variety of groups, socialist and capitalist alike, and serves as a mouthpiece for London’s own politics. As Ernest becomes more prominent, large corporations begin to consolidate into even more powerful entities that, in turn, influence American government. This then spawns a “socialist landslide” in which many socialists are elected to office across the country, which in turn leads to a power struggle between socialists and Oligarchs that eventually turns violent, sparking open rebellion as many of these socialist politicians are jailed. Ernest emerges as a leader of the early rebellions and so Avis provides a firsthand account of the rise of the Oligarchy, or “the Iron Heel,” as Ernest calls it. Ernest is eventually captured and executed and Avis disappears, leaving the manuscript incomplete.

Throughout the novel, Meredith includes explanatory notes and provides running commentary on the events taking place in the manuscript. Some of Meredith’s notes add historical context for his readers, others comment on Avis’ word choice or explain anachronistic word usage, while still others offer subtle critiques of the seemingly primitive views of the time.1 Meredith looks backward, knowing what will happen to Ernest and his rebellion, and so is capable of taking on a fatuous tone.2 This contrasts with Avis’ narrative, which tends to be optimistic and looks forward to the success of the rebellion. The use of these two complementary plot elements allows London to speak in two registers at once: the first is the heroic tragedy of the failed first rebellion that leads to Ernest’s death and Avis’ disappearance, and the second is the historical context that Meredith provides which reveals the ultimate success of the rebellions to come.

The difference in perspective between the two narrators also develops a tension that serves as the foundation of its ironic, dystopian structure. Avis’ story alone is a naturalistic novel that seeks to reveal the plight of the working class.3 She spends much of the first half of the novel investigating the case of Jackson, a man who lost an arm while working in a factory in which Avis’ father owns a large stake, and thus receives an education in the ill-treatment of workers in which she is complicit. Meredith’s foreword and notes function as a frame narrative that presents the novel as a historical document for a far-distant future. We find out through the course of the novel and Meredith’s notes that some seven hundred years (and numerous failed rebellions) have passed between the writing of the Everhard Manuscript and Meredith’s present. It is this setting and treatment that change the nature of the novel from being a polemic about the state of the working class in America in 1908 to presenting the struggle of the working class on a broadly historic, nearly mythic timeline. Ernest and Avis’ story can be seen from the vantage point of the future as the beginning phase of a long struggle between classes that will eventually culminate in the utopian-sounding Brotherhood of Man.

Buy the Book

The Future of Another Timeline

The projection into the far future is not the only time displacement that London uses in the novel. He builds two separate time displacements into the structure of his novel that are equally important to his purpose. The first major time displacement is the setting of Meredith’s writing in the future, but London also displaces the narrative present of Avis’ timeline into the future several years from his own time period in 1908. This serves the major rhetorical purpose of creating a world for his reader that is easily recognizable as a potential future of their own world. London sets the Everhards’ story from about 1912 to 1932, beginning only four years after the date of the novel’s publication. London increases the realism of his text by including references to flesh-and-blood authors, contemporary politicians, and actual events and folding them into his narrative. In one example, London writes about the strike-breaking activities of the Pinkerton agency, figuring Pinkerton as a precursor to the Mercenaries, the Oligarchy’s private militia. London also mentions politicians such as Austin Lewis, an English-born socialist who ran for governor of California in 1906, and Carroll D. Wright, the first U.S. Commissioner of Labor.4 Also mentioned are writers such as Friedrich Nietzsche, labor unionists John Burns and Peter M. Arthur, and publisher William Randolph Hurst. London builds a veritable reading list for any reader who is interested in his ideas, and the novel is packed with possible next steps for a budding socialist in 1908 America.

London also expresses his distrust of religious institutions in the text by condemning them for not taking action on behalf of the working class. In an exchange with a bishop who becomes a friend, Ernest challenges the clergyman to speak out against the disastrous lack of child labor laws and protections of the day. Ernest asks him what he has done to protect “[c]hildren, six and seven years of age, working every night at twelve-hour shifts” (24). Not content to leave it at that, Meredith includes a note detailing various churches and religious leaders’ biblical support of chattel slavery.5

Like many of the best dystopian fictions, The Iron Heel derives from the author’s political convictions and builds a world that is an imaginative, but realistic, extension of the one they inhabit. In other words, the dystopian novel is a novel with a thesis: it has a specific point to make. The imaginative representation of a future in crisis helps the author to identify a current social or political problem as a warning. London was a strong proponent for unionization and worker’s rights, and so he writes about a future in which the working classes are crushed and unions are decimated. The entire novel expresses London’s socialist perspective and serves to offer caution against the consolidation of large corporations. London’s protagonist, Ernest Everhard, sees the thin end of this wedge far in advance of his compatriots and works to spread the message and convert those he can. Arguably, the novel positions London himself as a similar sort of harbinger.

Beyond the narrative elements, the structure of The Iron Heel is innovative and would be adopted by many other dystopian works, as well. Both Margaret Atwood and George Orwell use a similar narrative trope in their own dystopian novels. Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Orwell’s 1984 both feature addenda to the ends of the novels that provide historical commentary on the narrative. Atwood reveals in her epilogue that, as in The Iron Heel, the preceding accounting of events were contained in a found manuscript and that the Republic of Gilead has fallen and things returned to a more-or-less normal state. Orwell likewise signals the end of Big Brother and the Party with the fictional essay, “The Principles of Newspeak,” that is at the end of the novel. All three novels share a similar ironic structure that allows even the bleakest of narratives a spark of hope by placing the current strife in a long historical context in which right does win out.6 In each case, the author also is careful to avoid describing what, exactly, leads to eventual victory. The actual struggle is cut out and there are very long stretches of time in between.

This novel, and others like it, serves a larger purpose for both the writer and the audience. London assuredly was looking to change people’s minds—his goal, like that of Orwell and Atwood, is to shock the audience with a vision of what might come, but also to provide a call to action. The unspoken point then, may be to remind us that these hideous futures may not need to happen. These stories and struggles are projected beyond the present to show us that these futures can (and must) be averted. The common thread in London’s work goes far beyond stories of outdoorsy men and wolves: it is survival. And while it might not be apparent on first glance, The Iron Heel is as much about survival in the wilderness as any of his other novels.

Matthew Raese teaches English part time for Kent State University at Stark, works full time in logistics, and writes — mainly about books and music but is trying fiction — in his spare time. He earned his doctorate in literature from the University of Tennessee where he specialized in contemporary American literature and literary criticism. Matthew lives in Ohio with his wife, their dog, and two cats.

[1]Describing prize-fighting, Meredith tells us that, “In that day it was the custom of men to compete for purses of money. They fought with their hands. When one was beaten into insensibility or killed, the survivor took the money” (7).

[2]Meredith also seems to like to correct Avis, even to the extent of her own husband’s involvement in the Second Revolt: “With all respect for Avis Everhard, it must be pointed out that Everhard was but one of many able leaders who planned the Second Revolt” (5-6).

[3]Naturalism would have been one of the most influential literary traditions just prior to the time London was writing this novel. Basically, it is an extension of realism that attempts to render human actions as one would for a scientific subject; by representing human drama in this purportedly “objective” light, the authors mean to reveal the true nature of humanity. Many of the authors associated with naturalism wrote about the treatment of the working class, resulting in novels such as Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle,” Frank Norris’ “McTeague,” and Stephen Crane’s “Maggie: A Girl of the Streets.”

[4]Wright wrote such books as The Relation of Political Economy to the Labor Question (1882), The Present Actual Conditions of the Workingman (1887), Some Ethical Phases of the Labor Question (1902), and the pithily titled Statistics of Drunkenness and Liquor Selling Under Prohibitory and License Legislation (1879).

[5] London includes greater detail and specifics on this matter than I include here.

[6]There has been some critical discussion about the endings of these novels and how hopeful they actually are. “1984”’s ending is merely suggestive of an end to Newspeak and, by extension, the politics backing it up while the ending of “The Handmaid’s Tale” shows that equitable treatment of women remains an issue after the end of Gilead.

Just to be pedantic, in the Handmaid’s Tale, it’s not a manuscript but a collection of tapes with Offred’s voice narrating. IIRC the historian uses this as one of the factors that made him decide the tapes were genuine as it took him some time to build a machine to play the tapes as the technology was obsolete by then.

It’s been a couple of years since I read this one, but I remember thinking that it was quite prescient in predicting a (then near-future) general Great Power war, and the rise of an ideology that wasn’t yet called fascism.

It was quite a gripping read, actually.

good post, thanks

I’ve got a copy of this on the shelf, but never got around to reading it. You remind me that I should do that.

@2 This summary of the novel makes it sound like the establishment of a Banana Republic than the establishment of Fascist Italy. It appears to have no more ideological system than K Street.

I’m not sure I would go that far. The essay could easily have come from a future edition of The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism. Which would be perfectly compatible with the continued existence of Oceania, and continued triumph of the Party.

@@.-@ I hope you enjoy it!

Came here just to say that Jack London was a total babe.

Shallowly and Superficially Yours,

Bel.

It was a terribly written book. Very reportage-esque. Forgettable.

@6 I am pretty comfortable with this interpretation. I would agree that there is no direct textual evidence to suggest the end of the Party but I think that there is something in the tone of the essay to suggest the end. The author writes very frankly about the mind-control aspects of Newspeak in a way that seems out of character for the Party. Also, I interpret the rendering of the Declaration of Independence in Newspeak as simply “crimethink” to be a nod in the direction of a more open society.

Your suggestion is plausible, given that we have no hard evidence to suggest otherwise, but I think it needs at least as much interpretive extrapolation as my own conclusion

Not a great book, but, still a must-read, just for the reasons mentioned. The contrast in tone of the 2 differing accounts of the revolution(s) is key. Optimism itself is a political act. Never doubt that the world can be fundamentally changed, but expect there to be costs.