In this biweekly series, we’re exploring the evolution of both major and minor figures in Tolkien’s legendarium, tracing the transformations of these characters through drafts and early manuscripts through to the finished work. This installment looks at the development and ultimate fate of Maedhros, eldest son of Fëanor—one-time high king of the Noldor, and foe of Morgoth.

The tale of Maedhros is one of the more tragic histories that Tolkien ever penned. Tolkien repeatedly emphasizes the elf’s potential to become a great leader and a spiritual warrior, a hero of great renown fit to stand alongside Beren, Lúthien, Glorfindel, and others. And yet, time and again, Maedhros’s heroic and self-sacrificing impulses break through the gloom of the first ages of Middle-earth only to be quashed and denied by the destructive power of the infamous Oath. Maedhros is an elf doomed from the first; his heroic actions and potential are driven into the dust and ultimately come to naught. Perhaps because of the tragedy and futility of his life, Maedhros has become a favorite among fanfiction writers, many of whom have, in wrestling with the elf’s often-troubling role in many of Middle-earth’s misfortunes, mined the depths of the emotional anguish and trauma lying just beneath the character’s surface. Maedhros attracts such devotion, it seems, because he exhibits the same characteristics that mark others out as heroes—but is kept in chains and ultimately destroyed by rash words spoken in his youth and by a cruel injunction from his dying father.

While the Noldor are still in Valinor, living among the gods, Maedhros remains practically anonymous, at least in the scope of The Silmarillion. He is simply one of Fëanor’s seven sons. Of them as a unit, as the children of Fëanor, we know only that some have the temper of their mother, Nerdanel, and some take after their father. At one point Tolkien writes that Curufin alone shared his father’s temper, but given stories of Caranthir and Celegorm especially, I suspect this was an assertion that later would have been qualified or removed altogether. Originally, Maedhros was closely aligned with his father; in the earliest drafts he is captured and tortured by Morgoth because he refuses to give up the Noldorin secrets of gem-craft (The Book of Lost Tales 1, hereafter BLT1, 271). From this we can assume that Maedhros has followed in his father’s steps as far as craftsmanship goes. But this notion fades away as the narrative develops, and Maedhros is never again explicitly identified with a craft.

In fact, as Tolkien revises, Maedhros is associated with Nerdanel and her craft, rather than with Fëanor and his. First, we know that Maedhros preferred to use his mother-name, Maitimo, and was remembered by it rather than by his other names: Maedhros, Nelyafinwë, and Russandol (The Peoples of Middle-earth, hereafter PM, 355). I read this as an intentional alignment with the sentiments of the mother above the father, a sort of memorial to Nerdanel, who was scorned and driven away by Fëanor. Maitimo means “well-shaped one,” which recalls Nerdanel’s genius for sculpting and bringing to life figures so realistic that they were often mistaken for living things. Secondly, Maedhros “inherited the rare red-brown hair of Nerdanel’s kin” (PM 353). Thus, not only does Maedhros choose to carry his mother-name—he also bears in some respect the image of his mother and her people. And again, given that Nerdanel was a sculptor, to whom image and physicality would have been of utmost symbolic importance, it seems possible that in marking Maedhros as like his mother’s kin in form, Tolkien was subtly commenting on the son’s inclinations. Maedhros could be seen as a work of Nerdanel that has been brought under Fëanor’s possessive control.

However, when Fëanor swears his blasphemous Oath, all his sons are there by his side; we are not told that any of them hesitated in swearing the Oath after their father: in fact, they all did so “straightway” (S 83). Neither does Maedhros stand out during the first Kinslaying, which involved the murder of the Teleri by the Sea and the theft of their white ships. It is not until the company is preparing to cross over to Middle-earth that Tolkien begins to add depth and color to his characterization of the Sons of Fëanor. Maedhros is first notable in The Silmarillion for the fact that he “stood apart” during the burning of the ships at Losgar, refusing to betray his friends despite the Oath and in disregard of his father’s anger. This is also the moment in which we first learn that Maedhros and his cousin Fingon had been dear friends before Fëanor’s rash words came between their families. This is a powerful moment in the text, and one that Tolkien uses to heal the breach between the two clans. Later, Maedhros will lament his part in the Kinslaying and attribute it to rash youth caught up in the madness of a persuasive leader.

Interestingly, though, in the very earliest drafts no oath is sworn until much later, and Fëanor is not present for its swearing. Instead of the Oath springing from Fëanor’s fey mood and mistrust of the Valar in Valinor, it is prompted by Maedhros’s capture and imprisonment in Angband, which occurs while he is away searching for the Silmarils. In “Gilfanon’s Tale: The Travail of the Noldoli,” we’re told that because of this, “the Seven Sons of Fëanor swore an oath of enmity for ever against any that should hold the Silmarils” (BLT1 271). This tale is, actually, the first appearance of Maedhros as we know him; previously, the name was given to Fëanor’s grandfather. Only as Maedhros’s true role in the narrative emerges do the stories of the infamous Oath—sworn in Valinor and in anger against the Valar—appear.

At this point, we start getting a clearer picture of the Maedhros who will take up his father’s mantle of leadership. In his abandoned alliterative verse poem, The Flight of the Noldoli from Valinor, Tolkien’s conception of Maedhros (here spelled “Maidros”) is more detailed: he is explicitly set apart during the Oathtaking by the following lines, in which he is described as

…Maidros tall

(the eldest, whose ardour yet more eager burnt

than his father’s flame, than Fëanor’s wrath;

him fate awaited with fell purpose)(FoG 35-36)

Here Tolkien imagines Maedhros as even more passionate and driven than Fëanor—a radical claim given what we know of the “spirit of fire.” These lines, though they never appear in the published Silmarillion, are significant and suggest that the motivations and goals of father and son will come head to head. I have already argued that Maedhros is more like his mother than his father, and in these lines the friction between father and son is implicit. Maedhros is ardent where his father is wrathful—a key difference. But the final phrase is dark, giving us to understand that Maedhros’s spirit will in time be overcome by a dark fate. To Christopher Tolkien, this fate is the capture and torment on the cliffs of Thangorodrim (The Lays of Beleriand, hereafter LB, 165), but I would add to this that Maedhros’s entire life is fraught by the tension inherent in the above lines: his entire life is turned without reprieve toward a “fell purpose.” His passionate spirit is repeatedly challenged—and ultimately overcome—by the doom that ensnares him.

Fëanor’s death only produces more problems for his sons. At first they are bound to the Oath by their own words, but they also become compelled by the further injunction of their father, who, merciless even on his deathbed, “[lays] it upon his sons to hold to their oath, and to avenge their father” (The War of the Jewels, hereafter WJ, 18). After Fëanor’s passing, Maedhros becomes high king of all the Noldor, but he is, understandably, more focused on assaulting Morgoth. And while he is quite clearly accepted (by most) as a military leader and strategist, the idea of Maedhros as high king is never really developed by Tolkien and is left to fitfully haunt the background of his narrative. (Remember that Maedhros chooses not to use his patronym, Nelyafinwë, which means “Finwë third,” referring to his status as the heir of both Finwë and Fëanor.)

It is during this campaign against Morgoth that he is captured and kept a prisoner in Angband. When his brothers, fearing Morgoth’s treachery, refuse to treat for his release, Maedhros is chained by the wrist to the peak of Thangorodrim and left there to suffer, becoming Middle-earth’s original Promethean archetype and a sort of early example of a spiritual warrior undergoing initiation. After an untold number of tortuous days, he is saved by Fingon and a great eagle sent from Manwë, though he loses his hand in the process. This moment is particularly significant because it is not unlike the powerful spiritual initiations undergone by characters like Gandalf and Glorfindel. Maedhros is assailed by a demonic enemy, experiences great torment, and is brought through that torment into new life and power by an eagle, a symbol of the soul’s ascent or ecstasy. This experience plays itself out in an interesting way and suggests that Maedhros is entering the company of spiritual warriors of unsurpassed power. He recovers because “the fire of life was hot within him, and his strength was of the ancient world, such as those possessed who were nurtured in Valinor” (LR 277). At this point he relinquishes the earthly kingship of the Noldor and devotes himself to battling the demonic might of Morgoth. In this role, the fire of his spirit bears testament to his spiritual transformation.

During and after the Dagor Bragollach, the Battle of Sudden Flame, “Maedhros did deeds of surpassing valour, and the Orcs fled before his face; for since his torment upon Thangorodrim his spirit burned like a white fire within, and he was as one that returns from the dead” (Silmarillion 152). The comparable passage in The Lost Road clarifies that “the Orcs could not endure the light of his face” (LR 310). Here Maedhros can be identified with Gandalf, who dons garments of blinding white upon his return; Glorfindel, who transfigures into a “shining figure of white light” as he faces the Nazgûl (The Lord of the Rings I, xii, 214); and Frodo, who is compared multiple times to a clear glass filled with light. Maedhros’s transfiguration thus marks him as one who has passed through “death” into ecstasy, but it also sets him apart “as one that returns from the dead” (152). The phrase’s shift into the present tense highlights the process of returning rather than the result of returning, a small but significant change indicating that this transfiguration is a continual rising from the dead rather than a one-time escape from torment. Maedhros’s death(s) and resurrection(s) are cyclical and unending, not in the past but always ongoing in the present. The sentence’s construction also signals a future event: i.e., Maedhros is here characterized by the fact that he does not, as it were, stay dead. He is always in between, always experiencing the power of his rebirth.

But, unfortunately, Maedhros’s new life is constantly under attack by an enemy he cannot escape: the Oath that will drive him whether he keeps it or no. He becomes Morgoth’s greatest adversary, but his heroics are compromised by fate. At this point the texts are full of references to Maedhros’s despair and heaviness of spirit. He lives with “a shadow of pain […] in his heart” (LR 277); he repeatedly “forswears” his oath. He is “sad at heart” and looks on the Oath “with weary loathing and despair” (The Shaping of Middle-earth, hereafter SM, 189). Eventually, he is forced by the power of the Oath to make war on his kindred, which leads to a third Kinslaying, and even to threaten war against the Valar when the latter recover the two remaining Silmarils. At this point in the narrative we see the true extent of Maedhros’s torment. He has lost his mother through exile; his inheritance through tragedy; and his father, his dearest friend, and all but one brother to violent deaths. And he himself is brought in the end to despair. In one draft, Tolkien writes of Maedhros that “for the anguish of his pain and the remorse of his heart he took his own life” before Fionwë, herald of the Valar (SM, 190). In later drafts and in The Silmarillion, Maedhros casts himself into a fiery chasm, where he and the Jewel are devoured.

Buy the Book

Fate of the Fallen

I find Maedhros’s tale all the more tragic because of the small tokens of hope scattered throughout the material Tolkien was never able to develop. For example, according to Unfinished Tales, Maedhros is the first bearer of the Dragon-helm of Dor-lómin (he passes it on to Fingon as a gift; it later makes its way to Húrin and, eventually, the hapless Túrin) (80). In many of the tales, Tolkien chooses to emphasize Maedhros’s reluctance to pursue the Oath’s fulfillment and his regret over all the harm it has caused. In a fascinating but incomplete story, Tolkien writes that a “Green Stone of Fëanor [is] given by Maedhros to Fingon.” Christopher Tolkien explains that although this tale was never fully written, it “can hardly be other than a reference to the Elessar that came in the end to Aragorn” (WJ 177).

Even more significantly, perhaps, one draft suggests that Maedhros (rather than Fëanor) rises again during the end times’ battle against Morgoth and breaks the Silmarils before Yavanna, so that the world can be remade and the hurts caused by Morgoth (and the Oath) healed. This original impulse, though it is rejected later, is a significant one, both moving and satisfying. Maedhros longs to restore what his father destroyed and his hesitancy in pursuing the Oath’s fulfillment is marked and emphasized by Tolkien in the texts (though its intensity varies throughout the drafts). Maedhros also serves as a stark contrast to the actions and attitude of Fëanor; he is Fëanor’s revision. The idea of Maedhros at last being able to fully make amends by willingly giving up the Silmarils to Yavanna (for the good of all) must have appealed to Tolkien, even though he eventually decided it must be otherwise.

Ultimately, Maedhros plays the role of the tragic hero. He is a doomed man, one who fails to succeed even when he does all the right things with the appropriate courage. Like Túrin, Maedhros is under a sort of curse that actually transforms the way the heroic world functions: while men like Beren are appropriately rewarded for their valor, Maedhros is subject to a reversal of the proper working of the world. The unflagging despair with which he approaches his oathkeeping, especially as his life nears its end, reflects the impossible situation in which he finds himself. And what can be done? There are few options open to the Fëanorians, and none are particularly hopeful. Indeed, even an appeal to the all-father himself is pointless:

Yet Maglor still held back, saying: “If Manwë and Varda themselves deny the fulfillment of an oath to which we named them in witness, is it not made void?”

And Maedhros answered: “But how shall our voices reach to Ilúvatar beyond the Circles of the World? And by Ilúvatar we swore in our madness, and called the Everlasting Darkness upon us, if we kept not our word. Who shall release us?”

“If none can release us,” said Maglor, “then indeed the Everlasting Darkness shall be our lot, whether we keep our oath or break it; but less evil shall we do in the breaking.” (S 253)

Maedhros’s reminder is born of a depression that prompts him to regard with bitterness the absolute inflexibility of the Oath that renders each and every choice effectually null and void, in that breaking and keeping lead equally to madness and the ruin of whatever they set their hands to. The Fëanorian touch is the touch of death. As Maglor rightly recognizes, there will be no escape from the darkness that overtakes them.

The picture Maedhros presents is bleak. Unlike many of Tolkien’s tales, this one ends in hopelessness and despair. Maedhros finds himself condemned by the Silmaril and its holy light for his wrongdoings and, unable to endure the torment of his exile, he accepts the weight of his own and his father’s misdeeds and enters the fires of the earth’s heart as recompense. But this is not the purifying flame of spiritual ecstasy that set him apart after his trial on Thangorodrim. Despite Tolkien’s promise that he is “as one that returns from the dead,” Maedhros does not return.

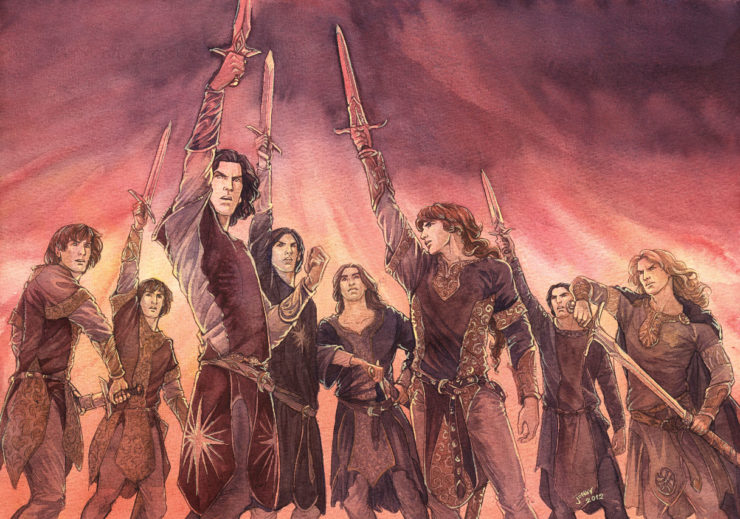

Top image: “It Ends in Flame,” by Jenny Dolfen.

Megan N. Fontenot is a dedicated Tolkien scholar and fan who finds Tolkien’s tragic and tormented characters practically irresistible. Catch her on Twitter @MeganNFontenot1 and feel free to request a favorite character in the comments!

I haven’t read enough about Tolkien to know if it’s documented that he ever suffered from depression. He clearly knew enough to describe it pretty well in his characters.

But, one of the defining characteristics of Tolkien’s heroes is that they resist despair. They continue trying to do the right thing even when they no longer see a chance at a hopeful outcome.

Another one of their main characteristics is mercy. The choice that may have determined the course of events and saved the world in The Lord of the Rings is Bilbo sparing Gollum in The Hobbit.

Maedhros may have fought the oath but, in the end when given a final choice, he chooses it. His choice is driven by hopelessness and despair. Also, even though his brother argues that the oath has been voided, he refuses to believe this.

His argument runs on two flawed assumptions. First, having sworn by Iluvatar, he rejects that Iluvatar’s chosen representatives who have been given authority over matters like this on Iluvatar’s creation, have the authority to void an oath sworn by Iluvatar even though the oath has put him in direct conflict with what he can reasonably assume to be Iluvatar’s will.

Second, Maedhros rejects the idea that Iluvatar can or will show mercy. He assumes obeying the Valar will put him under the doom the oath outlined and that Iluvatar will reject and condemn him because of an oath that should never have been sworn.

But, Maedhros’ biggest error is in rejecting Maglor’s argument. Maglor accepts Maedhros may be right, they may be damned (literally) if they do or if they don’t. But, if they are beyond mercy, they should make the choice that shows the most mercy to others.

Maedhros tries to claim he has no choice at this moment because of the oath, but he clearly does. It’s a rock and a hard place choice, but it’s still one that’s his to make.

nice artwork

Hi

This is a great series, it must require a tremendous amount of work, and I really appreciate the effort. It is certainly making me think I need to explore more of Tolkien’s work aside from the LOTR, The Hobbit and The Silmarillion.

All the best

Guy

I just listened to the end of the first age this morning on the audible version of the Silmarillion and Maedhros’s fate. I was thinking to myself “would it be so hard for the feanor kids to just throw the silmarils into the fire/ocean as opposed to themselves?” I mean if they’re (silmarils) destroyed via lava won’t that postpone the doom and fulfill the oath indefinitely even if it doesn’t negate it? seems maybe the sons just couldn’t take the burden of living with the doom anymore

@@.-@: Their oath was to regain the Silmarils; didn’t say anything about what they’d do with them afterward. They’d already at least partially fulfilled the Oath. Maedhros’s suicide was entirely about his own despair.

Another fantastic piece of character analysis in this series! Personally, I have never felt any sympathy for Feanor or his sons. Their evil was second only to Melkor in ultimately destroying all Beleriand and ruining Middle-Earth more than it already was, the First Age giving way to the Second Age on the back of unspeakable devastation and so much beauty lost. When I read his and Maglor’s fear about their oath, which led them to still steal the remaining 2 Silmarils, all I could think was “Get OVER yourselves! After all the deaths and destruction you have caused, all the brave people like Beren and Tuor and Glorfindel who had to fight and die, ensnared by this pointless jewel war, who died for good things, I’m supposed to feel sympathy for you?! Stop wallowing in misery and get back to Valinor to sue for pardon, if you get the Everlasting Darkness, it would still be the LEAST of what you deserve.”

@@.-@,

Maglor didn’t throw himself into the sea; he wandered off playing sad country-and-western songs. He eventually settled in the northern part of a forest near a mountain where it was rumored that a big shiny jewel had been found, sounding suspiciously like the gem that his brother Maedhros had carried with him into the earth. He changed his name to Thranduil, and, well, the rest is history…

I think this analysis overlooks an important time when Maedhros does not give in to despair–and it just makes things worse. After Beren and Lúthien recover one Silmaril, instead of making war on them, he “lifts up his heart” and gets Fingon and other allies to attack Morgoth in a massive force called the Union of Maedhros.

And it fails. Spectacularly.

He gets his best friend and rescuer Fingon killed because he had hope in a hopeless situation. After that, he gets darker and more despairing, more entangled with the Oath.

Maedhros is the one who get the gifts and miraculous intervention and it isn’t enough to change him enough to risk breaking the Oath or throwing himself on the mercy of Eru. Tolkien would have known about people like that.

The silmaril wasn’t destroyed by lava, no violence could mar or break them.

Hm…When Fingolfin arrived and marched directly toward the Gates of Angband, sounding the trumpet, Maedhros in his torment cried out toward the elves but it was lost among the echos of the rock…Then Morgoth covered the entire place with smoke and darkness to shield his force.

So during those few years before Fingon rescued, Maedhros had been in darkness and pain for nearly 30 years at that point, saw daylight for the first time, cried out for help, got plunged into darkness again while still being in the same pain as before…

You have to excuse him not thinking that the miracle was for him. It was obviously for Fingon.

> Their evil was second only to Melkor in ultimately destroying all Beleriand and ruining Middle-Earth more than it already was, the First Age giving way to the Second Age on the back of unspeakable devastation and so much beauty lost.

That’s a pretty distant second. Morgoth actively desired the destruction of anything he couldn’t control; Tolkien describes him in letters as a malicious nihilist, or thwarted solipsist. (My words for his longer description.) Morgoth, newly returned from Aman with the Silmarils, attacked Beleriand, killing King Denethor of the Laiquendi and besieging Cirdan’s Havens, which were rescued by the sudden appearance of the Feanorians.

The final Kinslaying was awful, but if Maedhros hadn’t done it, orcs would likely have sacked the Havens eventually — or sooner, without the rump Feanorians in between — and they wouldn’t have raised Elrond and Elros.

And the Feanorians weren’t the only ones to let pride and desire for the Silmarils lead them into error. Thingol and his line didn’t have the excuse of an awful oath driving them.

I don’t excuse what the Feanorians did; OTOH, they led actually doing something against Morgoth, which did some good for a while. It’s not clear if the Valar would have done anything other than pile up their mountains in fear.

I really love the characters that you chose for these articles.

@1, nicely said. I think it’s because I recently watched it, and so now I keep making parallels to it, but now I’m seeing a bit of Javert in him – unable to understand or comprehend mercy, and taking everything to an extreme letter of the law.

@10: I’m not confident that’s the case. My reading is that the Mouths of Sirion were protected by Ulmo – Sirion was Ulmo’s favourite of the ruvers, and we see his power there the most throughout the Silmarillion – and so it makes sense as a refuge for the refugees of Gondolin. Tuor’s prophecy from Ulmo to Turgon specifically instructs the Gondolindrim to “go down Sirion to the sea”.

The deepest tragedy of the Third Kinslaying is that the last safe haven from Morgoth on the mainland of Beleriand was destroyed by elves (just as Doriath under Thingol and Melian, which was also impregnable to Morgoth, was destroyed by dwarves).

It’s what makes the later years of the First Age so painful to read about. The Bragollach was just just about the Free Peoples being overwhelmed by force, and still had its bright spots, but from the Nirnaeth onwards, it’s all betrayals and internicine warfare and all that Morgoth has to do is sit back and nudge people in his intended directions.

Maedhros and Maglor make me unhappy. (I’m deeply invested in Fourth Age fanfics that let them find a happy ending.) But I’m not going to excuse any of their actions. The Oath was evil from the start; they could have and should have broken it.

It wasn’t the Dwarves who destroyed Doriath. Yes, they killed Thingol. But when Dior came to take his grandfather’s throne, and then the Silmaril was sent to him after the deaths of his parents, it was the Feanorians who killed Dior, his wife Nimloth, and left his younger sons (the brothers of Elwing) to die in the forest. It is why Elwing and the surviving Sindar are joined with Tuor, Idril, and the refugees of Gondolin at the havens.

It was a rather depressing life, to be threatened with eternal damnation on top of dealing with Morgoth wanting to kill everyone. Imagine having to fight under mental torment from the Oath – your own kind, the fight that had no logical reason to it, and would only worsen your own situation by risking your own supporters, you and your brother getting killed.

If it weren’t for the Oath, which promised the Everlasting Darkness or the mental torment,…

The Silmaril is definitely not worth it. Not worth it at all.

Though I still don’t understand why Maedhros couldn’t go with Maglor by the end.

Perhaps, he thought that by keeping the Oath, the worst they could do was die, which was the most likely outcome. While breaking the Oath, the worst outcome for them was to be cast into the Everlasting Darkness, after possibly doing something awful

But then again, if we look on the upside, surrendering themselves to the Valar yields a higher chance for them to escape the Everlasting Darkness and the Oath altogether. Not a guarantee, but it is a higher chance overall. Certainly higher than getting the Silmaril from the army that defeated Morgoth.

Then there is this poem I read recently that told me something on the decision:

“Why would you want to be a woman whose joys and sorrows in their hundred year of life were determined by others?”

Maedhros had always been the one deciding things in their family – to parley with Morgoth, to disinherite them, to move them away, to force them to fight Morgoth, to the Union, to repent, to withhold their hands, to what they would do…etc. Up until that point, it was always he who decided (aside from the times where Celegorm was involved – insulting Thingol, spotlighting as the villain in Beren and Luthien, leading the Second Kinslaying). Especially in the partnership between him and Maglor. He always leads. For better or worse.

So maybe, he just simply didn’t want to leave his ultimate fate – the fate of his very soul, in the hands of someone he believed had no fondness for him or his family. After all, didn’t it all end in the same way – Morgoth, Thingol, Dior, Elwing…anytime, his fate was in another person’s hands…it never ended well. They would all decide to ignore him.

So there it is – another decision: Do you want to leave it to others or do you want to do it yourself?

And that final decision doomed him.