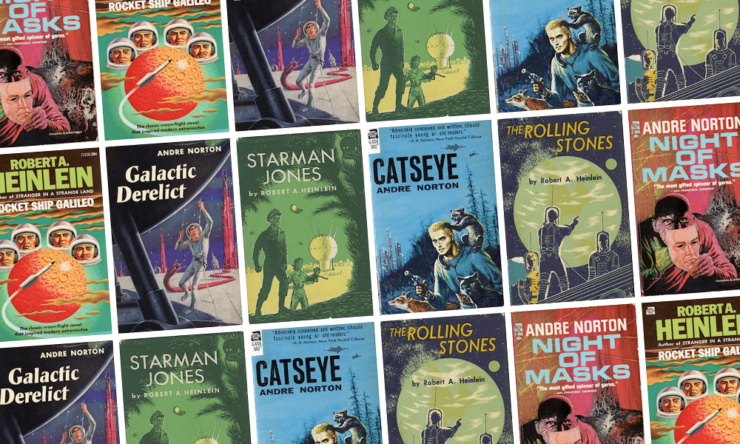

About five years ago, I reviewed all of the Heinlein Scribner juveniles (plus the two associated novels)1. Immediately thereafter, I reviewed fifty Andre Norton novels. This was not a coincidence. It just so happens that back in the 1970s, Ace re-published most of the Heinlein juveniles. Those editions usually contained a full-page ad for Heinlein’s Ace books and right next to it, an ad for fifty Andre Norton novels. Clearly someone at Ace thought the market for Heinlein and Norton overlapped.

So, how do their YA books compare?

Heinlein’s books are easy to read; the prose is fluent, if frequently halted for folksy lectures. Norton’s prose…well…it’s functional but stilted.

In the books written between Rocket Ship Galileo and The Rolling Stones, Heinlein was careful to make sure that his setting was plausible. Most readers might not notice this, but I did: he cared enough to get his orbital mechanics right2. This was much less the case after Starman Jones; the settings were interstellar and sketched with a lot of handwaving.

Norton was not at all concerned with scientific plausibility. She adopted the SF tropes that others had created and used them in the service of her plots. How did FTL and interdimensional portals work? No info. What we see is how her protagonists use the tech.

Something about Heinlein’s characters that eluded me when I was an idiot teen: some of his protagonists (in particular Rod from Tunnel in the Sky3) were not necessarily the sharpest pencils in the box. They’re always good-hearted fellows, but also naive enough to justify folksy lecturing from mentors. This also allows readers to feel just a little superior to the fellow who, for example, can’t seem to work out that another character is a girl even after he wrestles with her, then partners up with her (leading a third party to inquire, “Rod…were you born that stupid? Or did you have to study?”).

Speaking of women, none of the Heinlein juveniles first published by Scribner ever featured a woman protagonist. When women were mentioned, Heinlein’s treatment of them could be problematic. He could dismiss them as pesky (as he does with the domineering, not-so-bright matrons in several books). He could condemn them to domestic servitude (Meade in The Rolling Stones gets a lot more household work and lot less education than her dimwitted twin brothers4). But at least Heinlein mentioned women. In his later books, women could even be super-competent and boss the boys around.

Early Norton novels featured male protagonists and male major characters. Women were often missing, or if present, confined to extremely minor roles. One might think that human reproduction was carried out by budding. But Norton was writing what publishers wanted; she knew that there was a dearth of significant women in SFF. She wrote in 1971’s “On Writing Fantasy”:

These are the heroes, but what of the heroines? In the Conan tales there are generally beautiful slave girls, one pirate queen, one woman mercenary. Conan lusts, not loves, in the romantic sense, and moves on without remembering face or person. This is the pattern followed by the majority of the wandering heroes. Witches exist, as do queens (always in need of having their lost thrones regained or shored up by the hero), and a few come alive. As do de Camp’s women, the thief-heroine of Wizard of Storm, the young girl in the Garner books, the Sorceress of The Island of the Mighty. But still they remain props of the hero.

Only C. L. Moore, almost a generation ago, produced a heroine who was as self-sufficient, as deadly with a sword, as dominate a character as any of the swordsmen she faced. In the series of stories recently published as Jirel of Joiry we meet the heroine in her own right, and not to be down-cried before any armed company.

Norton started writing women protagonists in 1965’s Year of the Unicorn, to which women readers responded to quite favourably. However, “[m]asculine readers (…) hotly resented (Gillan),” according to the author.

Which brings me to the misogyny evident in the relative fannish regard for RAH and Norton. When Alexei Panshin wrote a book about RAH, no one seems to objected to the notion that Heinlein deserved some critical attention (though there were certainly objections to the critique). But when Lin Carter wanted to profile Norton, he had this experience:

When it first became known in the science fiction field that I was doing some research and gathering information towards a brief and informal study of Andre Norton, some people—both readers, and I am sad to say, a couple of “important” professional science fiction writers— asked me why I was wasting time on the work of a writer of “minor or peripheral value, at best.”

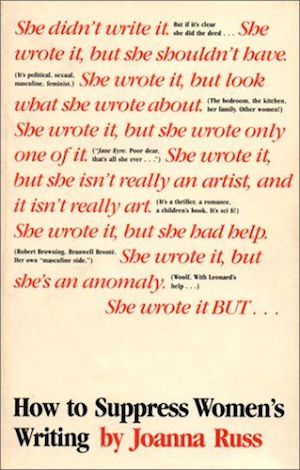

Has anyone ever written a book about the systematic erasure of women’s writing?

Oh, well… If such a book exists, no doubt someone will point it out.

There are, however, a couple of aspects in which Norton could be deemed Heinlein’s superior.

The first is that if one is the sort of reader who inhales books, Norton’s prolific habits are definitely a plus. Ace, after all, had eleven Heinlein novels for sale and fifty Nortons. Quantity has a quality of its own, and Norton was usually readable at the very least.

More significant: inclusivity. Heinlein was prone to carefully coded, deniable gestures of inclusivity—a character who was clearly Jewish, say, in a novel where the word “Jew” never appears. Careless readers could overlook their presence entirely. Norton, on the other hand, wrote books like Galactic Derelict and The Sioux Spaceman where the leads were explicitly not white. In the case of The Sioux Spaceman, white people were entirely absent, thanks to their enthusiasm for nuclear warfare.

Norton was also more inclusive when it came to class. Heinlein for the most part preferred to focus on middle-class boys who would grow into sensible middle-class men. Norton preferred to write about outcasts and the desperately poor. A Heinlein character might become a community leader or a promising officer. Norton protagonists like Troy Horan (Catseye) and Nik Kolherne (Night of Masks) do well to graduate from hunted criminals to marginal respectability. This may be due in part to Norton’s choice of settings: hers tended to be bleak. Sometimes there is no middle class—just the elite and the oppressed.

Did Heinlein read Norton? No idea. Still, I can think of two of his juveniles that border on Nortonesque. The protagonist of Citizen of the Galaxy starts off as a slave. He ends up as a man of wealth, but this is due to an unsuspected lineage, not to pluck and determination, and it is a very mixed blessing. If Norton had written him he probably would have been happy to stay on the Sisu. The other Nortonesque Heinlein novel is Starman Jones. Jones is born into rural poverty; by dint of hard work (and a bit of underhanded dealing, of which he later repents), he rises to a responsible position as an astrogator.

Did Norton influence Heinlein?5 Or are any similarities in their works merely parallel developments (like those beanstalks I mentioned a while ago?) What do you think?

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a finalist for the 2019 Best Fan Writer Hugo Award, and is surprisingly flammable.

[1]The classic Scribner juveniles begin with “Rocket Ship Galileo” in 1947 and end with 1958’s “Have Space Suit—Will Travel” (1958). 1959’s “Starship Troopers” was rejected by Scribner’s (ending Heinlein’s relationship with them) and published by Putnam. “Podkayne of Mars” (1963) was not apparently seen by its author as a juvenile but it certainly sold to people who purchased the juveniles.

[2]Heinlein did err when it came to calculation of the mass necessary to fuel torch ships. He was guilty of optimistic but inaccurate assumptions.

[3]Rod compensates for being just a bit slow by having a rare and wonderful talent: he asks for and *listens to* advice.

[4]This may be because Meade is a sensible, trustworthy girl who doesn’t need school discipline (whereas her brothers Castor and Pollux clearly need a firmer hand; perhaps a boarding school with a martinet of a headmaster). Or it could be that her father expects her to marry the first eligible man who proposes and doesn’t want to invest in skills from which other families will benefit.

[5]Speaking of questions of influence for which I don’t expect answers: is it a coincidence that the Norton novel that reads like a critique of H. Beam Piper’s “Space Viking,” a tale of interplanetary brigands told from the victim’s perspective, is titled “Dark Piper”?

[undefined]undefined

I am proud to announce that not only is it possible to write a footnote so long this site has trouble posting it, I have written two such footnotes. The first listed Heinlein’s juvies, the second the works in the Norton ad (arranged by year of publication).

The classic Scribner juveniles were

Rocket Ship Galileo (1947)

Space Cadet (1948)

Red Planet (1949)

Farmer in the Sky (1950)

Between Planets (1951)

The Rolling Stones (1952)

Starman Jones (1953)

The Star Beast (1954)

Tunnel in the Sky (1955)

Time for the Stars (1956)

Citizen of the Galaxy (1957)

Have Space Suit—Will Travel (1958)

1959’s Starship Troopers was rejected by Scribner’s (ending Heinlein’s relationship with them) and published by Putnam. Podkayne of Mars (1963) was not apparently seen by its author as a juvenile but it certainly sold to people who purchased the juveniles.

Here are the Ace editions featured in the ad:

Between Planets

Citizen of the Galaxy

Have Space Suit – Will Travel

Red Planet

Rocket Ship Galileo

The Rolling Stones

Space Cadet

The Star Beast

Time for the Stars

Tunnel in the Sky

The Worlds of Robert A. Heinlein

Why Ace didn’t have the complete run of juveniles, I can’t say. I can say it gave my set of juveniles a displeasingly inconsistent look, with two Ballantine editions mixed in with the Ace MMPBs.

3: And the fifty Andre Nortons:

1951 Huon of the Horn

1953 Last Planet, The

1954 Daybreak 2250 AD

1954 Stars Are Ours!, The

1955 Sargasso of Space

1955 Star Guard

1956 Crossroads of Time, The

1956 Plague Ship

1957 Sea Siege

1957 Star Born

1958 Star Gate

1958 Time Traders, The

1959 Galactic Derelict

1959/1961 Star Hunter and Voodoo Planet

1959 Secret of the Lost Race

1960 Shadow Hawk

1960 Sioux Spaceman, The

1960 Storm Over Warlock

1961 Beast Master, The

1961 Catseye

1962 Defiant Agents, The

1962 Eye of the Monster

1962 Lord of Thunder

1963 Judgment on Janus

1963 Key Out of Time

1963 Witch World

1964 Night of Masks

1964 Ordeal in Otherwhere

1964 Web of the Witch World

1965 Quest Crosstime

1965 Three Against the Witch World

1965 X Factor, The

1965 Year of the Unicorn

1966 Moon of 3 Rings

1966 Victory On Janus

1967 Operation Time Search

1967 Warlock of the Witch World

1968 Dark Piper

1968 Sorceress of the Witch World

1968 Zero Stone, The

1969 Postmarked the Stars

1969 Uncharted Stars

1970 Dread Companion

1970 High Sorcery

1970 Ice Crown

1971 Android at Arms

1971 Breed to Come

1972 Dragon Magic

1971 Exiles of the Stars

1973 Forerunner Foray

Heinlein was prone to carefully coded, deniable gestures of inclusivity

“Deniable” isn’t the word you want. It means “able to be plausibly denied”. Heinlein’s inclusivity was subtle, and, more to the point, delayed-action. You spend the entire book with Rod Walker before, in the last chapter, you learn he’s black – when he says to his big sister that Carol (who is explicitly black African from her first appearance) “looks a lot like you”. It’s only on the last page that we learn that Johnny Rico is Filipino. But neither of these are deniable.

Nor are all of them subtle, either. Women in Starship Troopers fight alongside the men, and are frequently explicitly described as better at it, and often in command. All the named female characters in the book are either commanding officers or on their way to becoming commanding officers.

When it came to including diverse characters, he was a hell of a lot better than some Hugo-winning authors writing today. Take a look at the character list for a Cixin Liu novel. If you’re really lucky, he’ll have included one white guy. Otherwise, monochrome.

In terms of the way I responded to the books when I was a kid, I’d say Norton’s vivid sense of strangeness and danger made a deeper impression on me than Heinlein’s breezy and rather cozy tales of competence rewarded… though I read both avidly. Heinlein was probably the better writer in the end, but sexism and the clubby atmosphere of American genre SF means his virtues have been so exaggerated and his flaws so downplayed that it hardly feels fair to make the comparison.

Orphans of the Sky, as I recall, was also eventually marketed as a “juvenile”. At any rate it was the first Heinlein book I read, age 12 or so. (For reasons I’ve never figured out, I only read a couple of the juveniles as a juvenile — Tunnel in the Sky for sore, and Starship Troopers (which I didn’t consider a juvenile), and maybe Space Cadet or Time for the Stars.

Heinlein called Podkayne of Mars a “cadet novel”, by which I think he meant aimed at a slightly older audience than the juveniles — but still not necessarily an “adult” novel.

The evidence Rod is black appeared equivocal when I reread it in 2014 but there’s no way to read the text except that interracial marriage is so accepted as to be unremarkable. Which to modern readers may seem like an odd point to dwell on but it was not until the 1990s, generations after Tunnel, that a majority of Americans thought interracial marriage was acceptable. Still, if Rod was intended to be black, it’s possible to miss the point given the evidence in the book, while nobody is going to argue about whether or not Travis Fox is Native American.

Mobile troopers are always men. Women stick to the navy, and from passages like

and

The two sexes don’t actually mix much.

I started reading Norton soon after discovering the Back of the Book in The Lord of the Rings. I loved her style because to me it seemed like a deliberate attempt, a la Tolkien, to remind the reader that the characters were from elsewhere and elsewhen. It seemed, not stilted, but translated. I have since read Pyle et al., who IIRC were her inspirations, and IMO Norton does it better: not only transporting the reader by use of style, but also creating relatable characters. (Yes, Pyle’s most famous story is a retelling of Robin Hood. I said the Eight Deadly Words about it.)

On the other hand, I bounced hard off of Heinlein’s juveniles because in my experience people who talked and acted like that tended to look through people like me (I have an alphabet soup of conditions that were all lumped under the general-use term “weirdo”)–or come after us.

Also, note I am comparing Heinlein to Norton, not Heinlein to authors he might compare more favourably to.

The evidence Rod is black appeared equivocal when I reread it in 2014 but there’s no way to read the text except that interracial marriage is so accepted as to be unremarkable.

I’m not sure about that, to be honest. Rod says to his sister: “Caroline [who is explicitly black] looked a lot like you”. I suppose you could stretch that to mean that Caroline, who is black, was of similar build to Rod’s sister, who is white, or something like that? Doesn’t really ring true, though.

And what do you mean about interracial marriage? I don’t remember any suggestion that Rod’s parents are of different races.

The two sexes don’t actually mix much.

They serve on the same warships. Yes, MI are all male. I never suggested otherwise.Note that in the passage you cite, the guard is to separate MI from Navy, not to separate male Navy from female Navy.

Norton and Heinlein where the two most important authors in my teenage reading lists. They are the ones I remember now, decades later, and the ones I still reread again and again.

While we’re talking about Tunnel in the Sky, Rod’s family is explicitly described (early in the book) as non-Christian.

@8: James is talking about the marriages that occur during the (extended) class trip. Everyone seems to expect Rod to marry Caroline, Caroline has some interest in marrying a different man, who marries instead Margery Chung. At least one, and possibly all of these marriages would be mixed, and none of the students seems to worry about it. Thus James’ comment there’s no way to read the text except that interracial marriage is so accepted as to be unremarkable.

I think there’s more textual evidence supporting the idea Rod is asexual than that he’s black and as far as I know nobody but me thinks he might be asexual. Again, if this was a Norton, we would not be discussing this because Norton would have just said explicitly that the character was black.

am just going to snag a bit of text from my old review (now 0.3% as old as the fall of the Western Roman Empire).

“Should people of difference races marry?” never comes up. It’s a total non-issue. Not true of the US when the book was published.

(Heck, my parents caused a bit of fuss in the 1950s by marrying across religious lines: he was an Protestant atheist and she was a fugitive Catholic nun atheist. You may wonder “if they were both non-believers, does it really matter what religion their relatives were?” Yes, yes it did.

When my mother died, her sister really wanted her to have a Catholic funeral. Now, I don’t know how many of you have tried to arrange a Catholic funeral for a fugitive Catholic nun atheist. It turns out to be doable but tricky. )

Great article. I would be curious how Asimov’s “Lucky Starr” series reads today as well.

Also, a question: do you have any idea what book is Andre Norton referring to when she references “the thief-heroine of Wizard of Storm”? Searching Google and Amazon for that title didn’t turn anything up for me.

I adored the Andre Norton books as a child and later as a teenager. So happy the hear someone bring her up.

Wizard of Storms by Dave Van Arnam, maybe? That’s the closest I see in isfdb but I have never read it.

@11 Most of Heinlein’s juvenile protagonists were uninterested in sex, and clueless about women. They seemed to be firmly entrenched in what psychologists back in the day called the latent phase of sexual development. They were generally portrayed from 16-18 years of age, but when sex was concerned, acted like they were 10. Over the years, from hints I have gotten from letters, biographies and such, I have gained the impression that this convention was established by the publisher, not Heinlein himself.

Interracial marriage was explicitly a subject in The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, where Manny during a propaganda tour of Earth was arrested somewhere in the bible belt for (as I recollect) bigamy and interracial marriage.

I had thought that Farmer in the Sky was written for Boy’s Life, not Scribners, but I guess I was wrong on that point. Maybe it was serialized in Boy’s Life in addition to appearing in the Scribner’s series.

Thanks for the list, James, it is quite a useful document.

@14 That’s got to be it. Published in 1970, a year before On Writing Fantasy came out. Thanks!

For Norton fans, I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out at some point Judith Tarr’s wonderful Andre Norton Reread here on the site, in addition to James’ aforementioned reviews of her books–so I’m doing it here :)

AAAAAAAUUUUUUUGGGGGGGHHHHHH IN MY BRAIN I HAD A LINK FOR THE TARR REVIEWS.

Stupid brain. See if I give you any oxygen.

The irony for me, you go through that list of Hugo award winners and nominees over the last 60+ years, and we’d be really really lucky to find a book without a white guy.

Consider the rest of the Hugo award nominated authors from 2017: NK Jemisin, Charlie Jane Anders, Becky Chambers, Yoon Ha Lee, Ada Palmer. A list comprised of female authors from different ethnic backgrounds. If anything, the current zeitgeist is diverse

Yoon Ha Lee is a man.

It occurs to me now that many of the futures depicted in Heinlein’s novels are rather bleak. In “Farmer in the Sky” and “Time for the Stars,” Earth is overpopulated and resources are becoming scarce. In “Starman Jones,” economic mobility is limited by the hereditary “guilds” that control space-travel related professions. In “Red Planet” the Martian colony is run by corrupt, nepotistic bureaucrats whose cost-cutting plans would jeopardize the colonists’ lives. In “Between Planets,” in addition to oppressive rule over the Venus colony there is a system-wide secret police organization that resorts to torture and murder to maintain rule. In “Space Cadet,” global peace is maintained under the shadow of the constant threat of orbital nuclear weapons. In “Have Space Suit Will Travel” Earth’s fate is under ongoing review by galactic council. Altogether, most of the Heinlein-verse seems to be a nice place to visit (in print), but I don’t think I’d want to live there.

Norton’s books had a lot more of the results of war. Heinlein might mention ‘New Chicago ‘ or ‘they blew up Buenos Aires,’ but his characters didn’t live it.

Norton’s characters do- the Dipple is a constant across many planets, and her protagonists actually suffer real want.

Also, in Norton’s books the long-term survival of civilization- or humanity itself for that matter- is doubtful, given the number of her books that deal with researching vanished alien Precursor civilizations. Ones that are vanished except for their artifacts.

Hi I loved this post and enjoyed the comments. As you mention aside from Citizen of the Galaxy and Starman Jones Heinlein’s characters seemed to be fairly affluent. I loved your comparison of H. Beam Piper’s “Space Viking,” and Nortin’s “The Dark Piper, I had never made the comparison but it is a really interesting idea.

This period of her life described here in the Wikipedia article on Norton, “During 1940–1941, she worked as a special librarian in the cataloging department of the Library of Congress.[9] She was involved in a project related to alien citizenship which was abruptly terminated upon the American entry into World War II.” has always interested me. Norton in her work shows you the results of war, and a number of books, Catseye, Night of Masks, Judgement on Janus feature protagonists who originate in the Dipple, basically slums for displaced war refugees. I think you have captured the fact that Norton did present a very different class of protagonists with very different expectations than Heinlein’s. In one interview she did admit she preferred characters without family ties as this limited parental involvement. It also spared them the lectures Heinlein’s characters had to sit through from the many father figures in his work.

Great post, I read them both and I still like a number of Heinlein’s juveniles, but Andre Norton is the only author I have every written too, when I learned she was ill, and she will always have a special place in my heart.

Happy Reading

Guy

In Tunnel Rod is black according to Heinlein. All mentions of race and sex are carefully finessed in the juveniles because of his editor at Scribner’s.

I stole like a thief in the night into my older brothers room when I was a kid (forbidden territory) and smuggled out his paperbacks and read them. He had all the Heinlein’s and all the Norton’s and while I devoured Andre Norton’s books, the Heinlein never caught my fancy. I’d be hard put to pin down a favorite among Andre Norton’s books but the “Moon of Three Rings” series, Catseye, and the Beastmaster books are always favorites that have been re-read many times. (I now have my ‘own’ collection of Andre Norton :D…) My co-worker adores the Heinlein juvenile stories so I may have to give them a try once again.

Parents are always a problem in YAs. For some reason, people expect parents to be helpful in a crisis (presumably these people are either amnesiacs or orphans.). Thus solutions like “parents dead” or “parents somewhere else.” “Parents _are_ the problem” is also a valid answer.

Although Tanith Lee didn’t write a lot of YA, she _loved_ the orphan solution. When I did a A Year of Tanith Lee [1], I read 48 novels, which featured among them 44 absent mothers, 1 absent mother figure, 36 absent fathers and 1 absent father figure. The parents who did appear made a good case that the orphans had it better.

1: Which lasted more than a year because I wanted to synch the beginning of projects with the beginning of the calendar year.

@8: Rod says to his sister: “Caroline [who is explicitly black] looked a lot like you”.

I’ve learned through hard experience not to quote from memory. What Rod actually says to his sister is “She’s a big girl, even bigger than you are – and she looks a bit like you.”

There’s a difference between “a lot” and a “bit.” As James said, “deniable.” I’m not interested in denying that RAH could have intended Rod to be black, nor do I think James is. The difference is that Norton was more likely than Heinlein to be direct in her juveniles. Yes, we know that Caroline is black, but she’s not the protagonist, which probably made a difference to Scribner and would probably have made a difference to white readers in the 1950s. Nor was this limited to Heinlein’s juveniles: he played similar games with Eunice in I Will Fear No Evil, a decade later, for a nominally adult audience.

Later in Tunnel, there’s a little family fuss over a “wild man” photo of Rod, which could also be meant to imply that he is black. But at the end of the book as he leads a wagon train to the stars, we’re told that “he wore a Bill Cody beard and rather long hair.” That could describe a black man, but it seems to me to be stretching it. Perhaps Heinlein’s visual imagination slipped there?

Earlier you wrote “Women in Starship Troopers fight alongside the men.” This is not true: all the actual fighting in the book is done by men, and though yes, “They serve on the same warships,” as James said, the sexes are kept separated by armed guards. I gather the movie depicted conditions differently, and maybe you’ve confused the two.

Our high school librarian was used to buying all the Heinlein juveniles in the Sixties and accidentally put Farnham’s Freehold in the mix with the others. It was definitely not juvenile, but I got to read it before it was pulled from the shelf.

Norton or Heinlein? As a child I read both in addition to many others. I wish that I remembered how Norton came into my life but I know how Heinlein came along. Thanks, Uncle Jack. Your books truly enriched my life immeasurably.

Thanks for the list of sequels to MOON OF THREE RINGS. Been waiting since 1966 for them. I bought them on Kindle just now.

Wonder what the record is for the longest period of time between reading a book & reading its sequel? It’s been 53 years…

29: Shades of the local video store that put anime tentacle porn in the kids section because animated features are for kids.

I believe I own all of the RAH juveniles but only a few selected Nortons. I guess that shows which I prefer.

#2: In Starship Troopers, tagalog is mentioned repeatedly all along the book. Plus the names of his classmates and friends. Plus other details. Actually, failing to notice the Johnny Rico is Filipino requires lots of inattention.

BTW, let us add an arguable comment: It makes sense that Heilein made his character a Filipino. People in Filipinas had a long story of infighting, then resistance against the Spanish, then resistance against the USA, then guerrillas against the Japanese. In WWII imagery, the people from Filipinas were natural warriors. Even if they had become comfortable, urgency might arise the fighter in them. As Heinlein thought to happen to the Homo sapiens species in general.

Arguable comment 2: Would you think that Zim is a Turkish family name?

Interesting, at least a little, that we have this longish discussion about differences in inclusiveness styles between Heinlein and Norton, but no mention that Norton wrote under basically a man’s name (certainly, my 10-15 year old self thought that she was a male author for quite a while). It wouldn’t have mattered to me, I was also reading Anne McCaffrey at the same time (just an example), and the same source (kids section at the library).

The editor at Scribner’s, Alice Dalgleish, didn’t think men could write novels with female protagonists, so vetoed any attempt by Heinlein to do so. Perhaps it stuck; in Podkayne of Mars, Podkayne is the narrator, but the protagonist is Clark.

This was not to say that there were not female characters who were capable of action. Betty Sorenson in The Star Beast appoints herself John Thomas’s and Lummox’s attorney and holds her own. (Miss Dalgleish was outraged, outraged, that Betty should have “divorced her parents”. Under the term “emancipation” this existed even in 1954, when the novel was published (and I was born).)

Leda in Citizen of the Galaxy is quite a devious and skilled character; she finds Thorby a lawyer willing to take on Rudbek & Assoc., aids his escape, and trips into the stockholders’ meeting, acting throughout as pure Valley Girl without a thought in her head — until the turns on her stepfather, shouts, “I vote for Thor Rudbek of Rudbek!” and saves the day

Not all the female characters are so independent, but then not all the male characters are independent, either. I could discuss the problems with Peewee Reinsfeld of Have Space Suit — Will Travel Perhaps I ought to do a revised edition of my book (Heinlein”s Children; Best Related Work Hugo Nominee 2007).

34: I knew Norton was a woman but I have absolutely no idea how I knew.

I loved all of Heinleins and Nortons YA novels when I was a kid and read all that I could get my hands on. But to me Heinlein wrote primarily SF and I got more into Norton’s fantasy. Maybe because those were when she was using female protagonists. But they were both responsible for introducing me to the genres.

As for comparing them, it would be hard. I think I found Heinlein to be an easier read, but not always a better read. And now I want to reread both.

I can say that I liked Heinleins juveniles better than a lot of his ‘adult’ novels which I often found self-indulgent.

As for race, I always thought of Rico in Starship Troopers as black. I guess I missed the part where he was identified as Filipino. But either way, the thing I hated about the movie was that they made the character white.

I liked the assumption in juvenile science fiction of a future where race would be irrelevant.

I did like that Heinlein would give his female secondary characters strong personalities. In fact, Podkayne of Mars was probably my least favourite even though it had a female protagonist because I found her a bit silly and she ended up in a traditionally ‘female’ occupation.

Despite having his bacon saved by her, Thorby is quite the patronizing so and so towards Leda:

@33, I wrote my comments before I saw yours. I don’t think as a teenager, I knew tagalog was the Filipino language, so my inaccurate assumption of race. Based on name, at the time I could also have assumed Latino. But for some reason, I thought of Juan Rico as black. But definitely never as white as depicted in the movie.

“Thorby had decided that ‘X’ Corps had missed a bet in Leda.”

People have different skills.

I mostly read Heinlein (Dad had a shelf full of mostly the juvies — Ace reprints which I didn’t realize until a few years ago were actually from the early 1970s and so slightly younger than me; I mistakenly thought they were his childhood copies), but I did also pick up at least some Norton along the way.

I remember having an argument with my parents at one point because I was convinced that Andre Norton was a woman and they were trying to persuade me otherwise; in their defense, I didn’t realize that Andre was actually a man’s name.

In re Tunnel in the Sky:

Wait, Rod is black?! I’m serious. I didn’t pick it up the couple of times I read the book. I had to think about it later to realize that Johnnie Rico was Filipino. Heinlein coded it pretty well.

African + Asian? Of course it isn’t interracial. Or at least nobody cared. It was white superiority, white purity, “moral supremacy” as a representative put it.

Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924, struck down in Loving v. Virginia. “It shall thereafter be unlawful for any white person in this State to marry any save a white person …”. At least they considered Indians, which other racists probably didn’t … but with more than a trace of Indian blood, they were considered non-white.

Representative Seaborn Roddenbery in 1912-13 proposed a Constitutional amendment with “Intermarriage between negros or persons of color and Caucasians… within the United States… is forever prohibited.”

I’ve seen a suggestion that, in internal debate about The Kiss in Star Trek’s “Plato’s Stepchildren”, it was suggested that Spock kiss Uhura. I suspect that it was suggested because there wasn’t anyone “white” involved.

@39: Movie? What movie? There has never been a movie made of Starship Troopers. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

“Heinlein was careful to make sure that his setting was plausible. Most readers might not notice this, but I did: he cared enough to get his orbital mechanics right.”

Farmer in the Sky, chapter “Line Up”.

I’m not sure about this. The Wikipedia article at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galilean_moons says that Io, Europa, and Ganymede are in a 4:2:1 resonance. But then some text appears to have escaped the talk page and suggests that there’s a relationship with a different set of coefficients, so I’m not sure.

I don’t know how but I knew Andre Norton was a woman from very early. Maybe not when I read Huon of the Horn (age 9 or so), but certainly by age 11 or so when I read The Zero Stone.

She originally adopted the pseudonym for her earliest juvenile novels, which were not SF. She legally changed her name to Andre fairly early — in 1934, long before she was writing SF (though some of her early work was fantasy, and much was historical.)

That said, she used the pseudonym “Andrew North” for some of her early SF, mostly I think the Solar Queen stories, which were first published by Gnome Press. Ace reverted to the Andre Norton name for those some time in the ’60s.

@36: I also knew (and no longer know how I knew) at a very young age that Andre Norton was a woman, so for years I was convinced that Andre was a woman’s name.

As a kid I assumed Andre Norton was male, like Andre the Giant.

Andre Norton’s The Stars are Ours was the first serious SF book I read as a child, and it totally hooked me on the genre, as well as profoundly changing my life. A world in which an oppressive anti-intellectual government sought to hunt down the remains of the inclusive and multiethnic “free scientists” looking for a way to preserve their lives and ideal… somehow had some resonance for an intellectual kid in a very oppressive and anti-intellectual small town.

For some reason it seems like it hasn’t lost resonance these many years later… I wonder why?

In any case her inclusion of female doctors and scientists, and the idea that origin mattered less than shared vision, left a strong impression (ethnicity didn’t really register, the place I grew up being almost entirely monocultural).

By comparison Heinlein’s inclusive gestures didn’t register at all — I remember only some positive comments about the Chinese on Venus in Between Planets (though in a sort of quaint ‘othered’ way, mostly remarks on their industry and that they’d send their bones back to be buried on Earth, views I am sure reflect the perspective in parallel to early US Chinese immigratrants/workers) and his women kept their competence under domestic wraps. For a man with no compunctions about preaching a belief system there wasn’t much to suggest sexism, classism, or racism were even things.

@james Davis Nicoll no. 31: That happened at my local mom’n’pop video store too! My husband and I were both aghast at seeing 12-year-old boys trotting in with dollar bills their moms had given them and happily leaving with ultra-violent action movies or rape fantasy porn. The owners shot us down time after time when we pleaded with them to stop stocking that stuff in the same section as the Disney movies and Saturday morning cartoon compilations just because it was animated.

One day my husband had a stroke of genius. He picked something (can’t remember what, just that I couldn’t sit through it) and asked the owners to watch it.

Next time we came in, that stuff was either with the R-rated movies or in the porn room you had to walk past the counter to get into.

Aside: I wish there had been a good movie or three made of something by Norton. The Gryphon series, maybe.

@@@@@44: ah, found the problem. The person who put the comments into the Wikipedia page was confused (he was looking at angular velocity). I’ll straighten it out. The three largest Gallilean moons of Jupiter are indeed in a 4:2:1 resonance, looking at the periods of each orbit. So yeah, Heinlein got it wrong, and Laplace got it right. (Assuming that it’s that Laplace, no later than 1827.)

@36, @46: I also always knew she was a woman, but that was because the first book of hers that I read (Forerunner Foray) had a blurb on the back referring to her as “she”. It didn’t strike me as strange, somehow. I just thought she had an unusual first name.

Now that is interesting, and I wonder what led RAH to write it, especially the inexplicable period of “702 days”. I expect he had astronomical reference as good for its day as Wikipedia is now (his library must have been catalogised, wasn’t it?); and where he just quoted scientific facts, he got them right.

What occurs to me is that either he noted that the “Orbital period (relative)” figures are not exact multiples (differing by about a percent), hence “the fractions don’t work out evenly”. Or perhaps he was talking only about a “perfect lineup” as opposed to lesser approaches, which makes some sense.

However there is one undeniable howler: as we can see in the animated scheme and he would have to read up in more detail, the resonance is arranged so that there actually never is a three-way conjunction; whenever Europa and Ganymedes align, Io is at the opposite side of Jupiter.

As for (that, indeed) Laplace, it seems Théorie des satellites de Jupiter, de Saturne et d’Uranus is the first part in the Volume IV of Traité de mécanique céleste, published in 1805.

P. S. Recently I read Space Cadet for the first time and recall not being quite convinced by some of the hard-science slide-ruley bits, but no details anymore. Except the wild implausibility of a ship hit by a meteorite just into the airlock just when it is open.

I read science fiction voraciously growing up but was never able to get into Andre Norton at all despite my high school library having a bunch of her books. Perhaps it was her “functional but stilted” prose.

I was reading an Andre Norton book as a kid when I noticed “science fiction” somewhere on the cover. It was a head scratcher. I knew what “science” meant (although this was a made up story, so it clearly wasn’t) and I knew what “fiction” was. But, “science fiction” seemed like an oxymoron (I didn’t know the word “oxymoron” but I got the concept). I asked. It got explained, and the light went on.

Mental dialogue that followed:

Wait, this is a thing?

This thing has a name?

(Looked at the book and realized I’d read other books like it)

I LIKE this thing!!!!!

@52 @JVjr: Hmmm. A StackExchange answer includes “Summary: I’m still researching, but there appears to be no well-known, reliable non-iterative method to find conjunctions”.

I read a few of Heinlein’s books and enjoyed them. But I devoured every one of Norton’s books that I could find, and loved them; I would read them again and again, which I don’t think I ever did with Heinlein’s books. But their writing was so different that it’s hard to compare them, like trying to figure out which fruit is better, grapes or bananas.

I knew that Andre Norton was a woman even before I found a note in one of her books that she was born Alice Mary Norton. I remember bugging my father to buy me her books whenever I saw them in a store, and I made some remark like “I really like her books!” My father tried to correct me, “Andre is a man’s name,” but I told him, “I don’t care; she’s a woman!” Later on I found one of her books that mentioned her birth name, and showed it to him.

I’m not sure focusing on the accuracy of RAH and AN technology references is all that fruitful. Both have some groaners, made all the more obvious by advances in the decades since they wrote. Most Sci Fi, and most Fantasy writing flourishes when the tech or magic inflect the human condition. And in that arena, as some of the commenters note, there are significant differences between Heinlein and Norton.

Norton takes a suspicious view of technology. Heinlein, less so.

Though he admits to pitfalls and perils of misused technology, Heinlein generally depends on it for the betterment of the human condition and the triumph of individual liberty (his subtext in a lot of books). Tech developments enable the underdogs to win in ‘Between Planets.’ Tech advances brought by aliens in ‘Have Space Suit, Will Travel’ at the end of the book hint at stabilizing earth society. Kinetic weapons and an AI liberate lunar society in ‘The Moon is a Harsh Mistress.’ Tech enables frontier expansion in ‘The Rolling Stones.’ For Heinlein, tech is a way to preserve or rebuild society. ‘Farnham’s Freehold’ shows us that even after an atomic war, the rugged individualist who has the needed tech skills and knowledge can overcome a big collapse.

Norton, meanwhile sometimes portrays hi tech as something to view with suspicion or something used by antagonists. The Kolder in the ‘Witch World’ novels are evil and inhumane. They come from a high-tech world. In ‘The Stars Are Ours’ and ‘Star Born’ Norton gives tech a double whammy. The refugees are scientists fleeing a totalitarian society that rejects the ill effects of technology and the wreckage wrought by tech use. They escape to a new world and a lower tech environment only to encounter a hostile alien remnant society squatting in the wreckage of its own tech war. The aliens use tech to dominate another species that humans ally with to save the day. ‘Time Traders’ and ‘Galactic Derelict’ have their own high-tech alien baddies. And since it is a time travel set of books readers find out the alien civilization collapses. Tech bad, human psi powers good. ‘Zero Stone’ and ‘Forerunner Foray’ show humans picking through remains of a lost high-tech civilization. Even here, technology is not a savior, it is something that humans have and use. But, the lost civilizations are a cautionary tale that tech alone will not make societies endure.

To apply some of the other commenters observations on othering and diversity of protagonists….for Heinlein, technology is a stand-in for the good things about conventional society. So, he tends to focus on the central power figure in his conventional time, young adult males. Norton’s more suspicious view of tech leads her to use women and under empowered characters in central roles more often than Heinlein.

Not a lot of this is my original thought. I vaguely recall an essay on Norton’s attitudes toward technology from an anthology of her short stories. I’ve used what I remember of that central argument. And thoughts on Heinlein’s emphasis on the superiority of the heroic individual are well developed by several critics.

My mother read me both the Norton and the Heinlein juveniles as bedtime stories when I was little. Soon I was wanting to read ahead on my own. I found them both equally enjoyable at the time, though I think Heinlein’s best (e.g., Star Beast, Citizen of the Galaxy) are slightly more re-readable, though Norton’s best (e.g,. The Zero Stone) are close. As a kid, my favorites were:

Star Rangers (Norton). I recall re-imaging Star Trek Gorn action figures as Zacathans

The Zero Stone and its sequel Uncharted Stars (for Eet, and also for the neat Thieves Guild stuff).

The Star Beast (Heinlein, also my mom’s favorite)

Red Planet and Rolling Stones (for the cute critters and the idea of used space ships)

Moon of Three Rings (for the nifty psychic powers/magic, body shifting, and dual narrative)

Citizen of the Galaxy (besides a neat narrative, I also remember enjoying the space battle against the pirates. Also, it seemed to take place in a universe with the same free traders as Norton.

Distinctions:

* Norton main characters tended to often have, or develop, telepathy and other mental powers and only a few Heinlein characters; these were a bit rarer in Heinlein (with some exceptions, notably Time for the Stars)

* Norton characters wielded futuristic zap guns like Blasters and Stunners, while Heinlein never seemed very interested in that stuff. (These things interest little boys who were also obsessed with Airfix model kits…)

* Heinlein and Norton both liked alien creatures, but Heinlein’s seemed more interesting, alien, and imaginative overall, while Nortons were more likely to be earthlike or variations of same with extra abilities.

* Norton had more cats and cat things. We had cats. I liked cats.

* Norton could be scarier than Heinlein. I remember a few passages in Norton that unnerved me as a kid, descriptions of floating corpses in space, ancient tombs, stuff like that. Heinlein had some tension and drama, but it was rarely scary stuff. (The scariest SF I recall as a kid was when I accidentally read, or was read, Brian Aldiss’ the Saliva Tree, when I was seven or eight, which gave me nightmares for a while…)

* Norton tended to give me more of a sense of living in a future non-western culture on an alien world, with more exotic names for many characters and places. Heinlein (Citizen opening excepted) had more of a familiarity to it.

* A lot of Heinlein novels were set on Earth or in the solar system. I don’t recall any of the Andre Norton sci-fi novels I read being set on Earth or even in our solar system (there were one or two historical or fantasy novels we also read by her).

* After I was old enough to start hunting my own sf novels in libraries and book stores, I continued to read both. I recall particular pleasure in finding Norton’s Perilous Dreams and Heinlein’s Starship Troopers when I was 11-12 and enjoying both.

“for Heinlein, technology is a stand-in for the good things about conventional society. So, he tends to focus on the central power figure in his conventional time, young adult males.” – @@@@@57. Charlie Schlenker

Um, I know Heinlein wrote the first version of Farmer in the Sky for Boys’ Life Magazine, the official magazine of the Boy Scouts of America. Checking Wikipedia, so was The Rolling Stones. More generally, the book series is called the Scribner’s juveniles — that is, they were published for, marketed to youth. Given prejudices about who would be attracted to adventure and science, putting teenaged boys in there would be expected.

Andre was not a common male name where I grew up, so I just assumed it was another version of Andrea and that she was a woman…

I think another significant difference was that Heinlein conceived his juveniles as having a pedagogic function, subtly or not subtly teaching the importance of math, hard science, space, and good character. I expect Norton may have had her own worldview that she wanted to bring across, but if so it was a lot more subtle. As a kid, though, Heinlein’s motives did not intrude on the story.

My rather left-wing parents were quite happy with both authors’ juvenile books, feeling they generally conveyed attitudes of tolerance and good morality. Besides Heinlein and Norton, the only other SF (as opposed to fantasy) I recall being read as a kid (in the early 70s) were the Asimov I, Robot stories and the John Whyndam novels,

One impression I carried away from Grumbles From the Grave, Patterson’s (laundry list) biography and even Panshin, is that some of the ‘modifications (that detracted in Heinlein’s Juveniles*) were dictated by Scribners’ editor Alice Dalgliesh …… I can not remember , right now, if Heinlein ever tried to go over her head? I think with Star Ship Troopers that Heinlein wanted to push Scribner’s button. At that late date why Schribner’s stuck to it’s ‘biz model’(?) for Heinlein is a mystery, Putnam made good money on that novel.

I will say this for Norton as a teen I tried Asimov and Wollheim‘s ‘YA; SF and was not pleased. Norton trumped them.

Norton for her around-the-edges techno-phobia , wrote some of best ‘urban’ (must be a better word) SF, I was transported by The Dipple setting on Korwar and stories became a bit lackluster when Norton moved on to her favorite pastoral settings!

*’Juvenile’ always rankled me since most all the protagonists in those Heinlein’s were YA, I guess Schribner’s used the legal definition of Juvenile to market them. It almost makes the books sound like they were for under 12 year olds, I know I didn’t read Red Planet till I was 13. Also, I have re-read those Heinlein books as an adult (and even as a more older adult) and found them entertaining, and for Norton , who I eat up when I was a teen, no so, I adored Norton’s Star Guard when I was 15 , I could not finish it when I re-read it at 35.

Earlier you wrote “Women in Starship Troopers fight alongside the men.” This is not true: all the actual fighting in the book is done by men

I would gently advise you, if your belief is that no one aboard a naval warship in wartime does any “actual fighting”, not to share said belief with anyone in the navy.

I know this: I read all of Heinlein, and most of Norton’s books, catch as catch can from school and public libraries. I bought most of the Heinleins, and Norton’s Witch World books, otherwise never bought a Norton new, and rarely used. Norton was writing pulp while Heinlein was trying, not always successfully but more often than not, to write Science Fiction.

Norton really liked all the space fantasy crap and had no sense of only using it when it was necessary: FTL, portable laser blasters, aliens who are basically humans in latex disguises, telepathy, ESP, telekinesis, maaaagic space cats and normal cats that become maaaagic space cats. When a story is based on telepathy, like Heinlein’s Time for the Stars, fine, but when it’s randomly thrown in because everything has all the crap thrown in, I’m unamused.

I can summarize and maybe quote from all the Heinleins. Little about most of the Nortons. Witch World is mostly setting bits, I couldn’t tell you characters or plots at all.

Dark Piper‘s not the only time Norton reacted to Piper, though. Crossroads of Time and Quest Crosstime are fairly blatant copies of H. Beam Piper’s Paratime stories, a decade after the originals were published. In Norton’s, the Paratime Police equivalent aren’t very useful and are more obviously company gun-thugs.

Heinlein’s future history was fairly coherent and self-consistent. Norton seemed to make a new universe up for each book, would recycle elements from the last one but ignore contradictions. Oh, yeah, Operation Time Search is a completely different time travel mythos than Crossroads, and I think there’s more.

What Norton had was: The ability to bang out a novel a month, or whatever it was. Michael Moorcock once wrote that a pulp novel should take no longer to write than it does to read. He may have been thinking about Norton there.

A more forgiving editor; or possibly no editor at all? Late Heinlein with less editorial domination went off into the weird areas of his OTO psyche, I’m not sure Norton had that in her. Unleashed, her id seemed to be pretty much stock ’40s-50s space fantasy, with traditional gender roles. There’s, uh, kind of a lot of rape in Norton’s books.

@57 has the tech angle right: Almost every Norton book seems like everyone’s miserable and all the amazing technology they have just makes things worse; only maaaaaagic can help them, and then not that much. Heinlein’s characters always turned every tech advance to their advantage, even if it had unfortunate consequences for the plot to work out. The few times Heinlein has magic (whether called psionics or whatever), it’s just treated like tech, something you can use and make your life better.

Heinlein’s characters (aside from Starship Troopers, which anyway isn’t a juvenile), are massively less prone to violence and colonialism than Norton’s. Norton’s solution to many problems is to kill everyone; often that doesn’t work out, but they are mean uncivilized people who pick fights, at least in the ones I recall well. Heinlein’s solution is to talk about it, get a lawyer, pay someone off, run away, fix the problem mechanically so there’s no more confrontation. If everything else fails, they’ll shoot or stab someone, but that’s like 10th on the checklist.

‘I would gently advise you, if your belief is that no one aboard a naval warship in wartime does any “actual fighting”, not to share said belief with anyone in the navy.’ — @@@@@62. ajay

Why not? It’s simple common sense. I was taught that by my father, a sergeant. He was very appreciative of the transportation arm of the Marine Corps.

@63 Heinlein less prone to violence? In Red Planet, the boys participate in an open, armed revolt against the authorities. And in Between Planets, the protagonist becomes a revolutionary who has learned to kill enemies with a knife, up close and personal, and participates in a space battle where the enemy is obliterated with advanced weaponry. In Tunnel in the Sky, the kids are dumped in a no-rules environment, where some of them murder each other to steal their gear. And in Have Spacesuit Will Travel, Kip kills one of the aliens by repeatedly stomping his head, something that is described in great detail. And that’s just ones I remember off the top of my head.

Tim @55: Well, the StackExchange discussion was about conjunctions in the original (I might even say astrological) meaning, i. e. “local minima” of angular distance between apparent positions of the planets as observed from Earth. Which is indeed a non-trivial four-body problem, especially where inner planets are involved. However, in the case of the outer ones, like the Great conjunction, the issue largely (certainly for the purpose of the first-order approximation predicting the date of the next conjunction, given the last one) simplifies to the intuitive formula for synodic period, 1 / T_syn = 1 / T_1 – 1 / T_2 . And this holds even more for the syzygy Heinlein originally described (both us and him ignoring a nice concidence that Ganymede, like Earth, is the third body in its system, but ordinary imperfect “conjunctions” of two other moons would occur daily). Putting in the periods of Ganymede and non-resonant Callisto, we get that their “line-up” should repeat every 12,52 days; but with the other two all over the place.

I really cannot imagine where/how Heinlein got the figure of 702 days, i. e. ca 1,92 years, which seems more appropriate for cycles of inner planets than moons with periods in the order of days. (Just for completeness and being aware of possible rounding error of the number given, that works out to 56,07 synodic periods given above; or 98,11 of Ganymedes and 42,06 of Callisto unless I made a typo somewhere. I haven’t been to google the method for finding approximations of common multiples of real-life, irrational numbers a la saros cycle that Heinlein might have tried to use, but I suspect that continued fractions would be involved.) Oh well, as soon as I get access to a time machine, this will be high on the list of things to find out.

Confusingly for this discussion, the British publication of “Witch World” novels, at least the paperbacks that I got hold of, placed “Year of the Unicorn” sixth, after three volumes of Witch World Kids. I would try to argue that “Witch World” the first (1963) already has significant female roles… but is it YA? Well – I found it readable when quite young, and there are fairly simple forces of good and evil in conflict… but quite a lot of thinking about sex, too (also, rape). That doesn’t rule out YA today though. (If Witch World witches do it then they lose their power, permanently. Or specifically if they do it with a man, but if there was an alternative then I don’t recall it being mentioned, or not to me.)

@KK:

It has been some years since I’ve read it, but Pod ends up either in the hospital in critical condition, or dead, depending on the version you read. (I’m assuming spoilers are irrelevant in this discussion.)

@mdhughes:

Heinlein was into Aleister Crowley? The only expansion of “OTO” I can think of is Crowley’s Ordo Templi Orientis.

God forbid a woman prefer babies to mathematics. As I recall Poddy is mulling over whether she wants to beat her head against a glass ceiling and if command is really what she wants as opposed to being a department head in a field that appeals to her.

@69/Roxana: Babies and mathematics? Both are great!

@68: Heinlein and Hubbard were friends when Hubbard was active in Jack Parsons’ Agape Lodge (and then Hubbard ran off with Parsons’ girlfriend and money—because he was a more powerful magician?). I’ve never seen proof that Heinlein was directly involved in OTO, and the only magic he ever showed any knowledge of in his writing was some Rosicrucian & hermetic stuff. But he knew Parsons, and he sure developed an interest in wife-swapping, polyamory, redheaded women, mind manipulation, biofeedback, and building a religion, which led up to Stranger in a Strange Land. Mike’s church is pretty much proto-Scientology without the monetary scam, which is itself just Thelema with UFOs and biofeedback devices. The sex-and-money cult part comes up a lot in Friday. Ginny Heinlein’s written some about the sex side, Hubbard about the religious (and took it practical, of course).

@70, Personally I hate mathematics. Poddy doesn’t, she’s good at maths but she knows all about the prejudice she’s up against.

great list

@33: BTW, let us add an arguable comment: It makes sense that Heilein made his character a Filipino. Not necessarily for their actual history; Filipinos in the US Navy of Heinlein’s time served only as messboys. I don’t know whether RAH himself was ever nailed down about this, but it certainly seems like another poke in the eye for unthinking prejudice. One can just imagine what a Heinlein still in service would have done with MacArthur’s stupid ~”The yellow man won’t fight” claim, that got us another couple of years of war in Korea.

@63: there are a lot of debatable statements in this comment, but Norton’s solution to many problems is to kill everyone; often that doesn’t work out, but they are mean uncivilized people who pick fights, at least in the ones I recall well suggests you recall few if any Nortons well. There are plenty of desperate people in Norton (as noted above), but violence tends to be the good guys’ last resort.

@61: “YA” is a recent term; “juvenile” was anything for neither small children nor adults, not a slur.

@63. mdhughes: “Heinlein’s future history was fairly coherent and self-consistent. Norton seemed to make a new universe up for each book, would recycle elements from the last one but ignore contradictions. Oh, yeah, Operation Time Search is a completely different time travel mythos than Crossroads, and I think there’s more.”

Unless she stated that she was going for a self-consistent imaginary future history, I see nothing wrong with this. Trying variations on a theme is creative. If it’s a series that requires continuity, like say The Expanse, then you want some rules.

Otherwise, insert Emerson’s “consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds” here.

Heinlein’s future history was made more coherent and self-consistent by pruning. Let There Be LIght was not often reprinted nor collected. The consequences of “We Also Walk Dogs” are ignored. The aliens disappear fairly quickly leaving a very much human centric universe in the future history and generally. Methuselah’s Children (1941) has some interesting aliens explicitly wiped from the scene by Lazarus later with no more explanation.

I find there is a background universe in much of Norton’s more SF writing that is consistent with it’s a big universe even multiverse with world enough and time. First In Scouts and other such are recurring fill in the background items and there is ample critical discussion of the common back ground to many of the books. Much inconsistency can be explained by the common bottoms up limited perspective view of society.

As for the Navy as a fighting et al force though of less significance to a story that doesn’t focus on the ship there is this:

I find myself still enjoying Heinlein and turning the pages eagerly on rereading what I consider the better part of his YA writings. Like say something from the Stratemeyer syndicate when I pick up an Andre Norton story I find that much of what I remember isn’t necessarily there – more a useful framework on which I could hang what I bring to the tale.

an interest in wife-swapping, polyamory, redheaded women, mind manipulation, biofeedback, and building a religion,

One of the items in that list stands out a bit from the rest.

” I want rustlers, cut throats, murderers, bounty hunters, desperados, mugs, pugs, thugs, nitwits, halfwits, dimwits, vipers, snipers, con men, Indian agents, Mexican bandits, muggers, buggerers, bushwhackers, hornswogglers, horse thieves, bull dykes, train robbers, bank robbers, ass-kickers, shit-kickers and Methodists!”

A little context for the movie quote above, for those who haven’t seen Blazing Saddles–but let’s not get off-topic. Thanks!

@75 It’s “creative” but also lazy, and part of why Heinlein gets ranked rather far ahead of Norton. Each book adds to the mythos, instead of you starting over from scratch and trying to figure out what she’s not telling you about the background.

@76 All those stories are collected. “Let There Be Light” is in a couple dozen printings of The Man Who Sold the Moon; “—We Also Walk Dogs” is in The Green Hills of Earth and The Past Through Tomorrow. isfdb is your friend. Both are canonical FH stories, and archetypical “lawyers, patents, and free information beat military threats” Heinlein stories. Light’s power is probably the key to that history being so much less terrible than ours, why they get space colonies 50+ years ahead of us.

@77 There’s also a quote from Justified, Raylan at a mineshaft: “I’m not afraid of heights, snakes or redheaded women, but I’m afraid of that.”

I really ought to go thru Judith Tarr’s Norton rereads and tally up the violent protagonists, against the Heinlein ones. It’s not going to work out well for Norton. Time & laziness vs. proving my impression correct.

@79. mdhughes: you obviously have a preference, maybe prejudice. But a writer not choosing or not intending to have a rigid framework for every story, to make them fit in the same sandbox, does not automatically become lazy. If the intent was there and she failed, you may have a point. Was all of Norton’s production meant to be internally consistent with the same imaginary history?

I became a SFF fan in the late 60s when I was in 5th grade from the conjunction of two things: my English teacher loaned me The Hobbit, and I found The Time Traders on the shelf in the elementary school library. I don’t remember when I found the Heinlein juveniles, but I probably glommed onto reading books with rocket ship stickers on the spine. I can see flaws now but I still love Have Space Suit, Will Travel and Space Cadet. On through junior high I read all the Norton SF I could find, but the Witch World books never captured me. The Zero Stone was the first hardback book I ever bought with my own (birthday present) money. I’m still fond of Time Traders, and I also liked the Hosteen Storm Beast Master books. I read Alan Nourse (whose books were conveniently alphabetically near Norton), the Lucky Starr books, and some others I got through the Scholastic book club. I moved on to Heinlein’s more adult books, some perhaps a bit early, and added in McCaffrey.

I was in high school when I left Glory Road lying around the house and my father, who had never read any science fiction, picked it up. He was a WWII and Korean Navy veteran and Heinlein clicked for him.

I’ve been reading/re-reading the Heinlein juveniles but you’ve all made me think that I should give Norton another shot. Back in the day I dropped Norton because it seemed like the middle of any Andre Norton book was a multi-chapter survival trudge through some desert/arctic wasteland/whatever where the hero was hungry, thirsty, and just barely hanging on. Multi-chapter wallowing in suffering just wasn’t was I was looking for. But maybe I picked the wrong books. I’ll give her another try.

@82. john-robert: Holy hell. Never read or watch The Terror then.

Canadians call that “camping.”

@82, @84: when that happened to Leonardo Dicaprio in a film they called it/him The Revenant. And he looked it.

@83: I take it that The Terror that you mean is the book/film/ship by Dan Simmons, but the title’s been used a few more times, including for a political movement in France (a while ago)…

@85. Yes, the one that was both a book and a TV series. Was the ship named after the French madness?

@86: John Franklin’s “HMS Terror” wasn’t the first or last, according to Wikipedia. Perhaps one of us is muddling it with “terroir”.

@87. Robert: Yes.

When I posted, there was only one Terror I knew of that was both a book and filmed series.

There’s an Edgar Wallace play/films/novel, but we could tell you didn’t mean that. The Franklin thing passed me by (sad ending I guess?)

Like the elephant, describing different parts of EW’s “The Terror” suggests a different story. To telescope a summary online: “The story begins with a daring gold bullion robbery during the First World War. Ten years later, at Monkshall, a country house where the ghost of a hooded monk is regularly seen prowling the grounds at night…”. So, one of those! And played straight, too. I think the principal person involved in either or both of these events is known as “The Terror”, which outside sports and politics is an extremely bad sign.

Andre Norton or Robert Heinlein… well, Android at Arms starts a bit like the haunted house bit, very very loosely. Our hero wakes amongst strangers, all significant people kidnapped and criminally duplicated… or is any of the players the duplicate him or her self… thus the title. I’m not sure what a criminal got from replacing people with copies who might not know they were copies. I suppose the copy could be bugged…

Andre Norton was the person who introduced me to sci fi, and fantasy, for that matter. I inhaled books as a preteen and would come home from the library laden with Norton’s books. That was because I finally saw myself in a book that wasn’t a romance, but had action, adventure, and a female hero. Heinlein was not nearly as accessible to my preteen self.

I picked up the Heinlein YA books from my father’s bookshelf at around 9 or 10 about 1980. He had them all, so I read them. Somewhere in the middle, I also started on Norton’s, but only the ones he had or that I could find in the local libraries. As I recall, I read everything of either that I could find. I inherited his collection, and those are still among the best stories present.

Criticism of Heinlein for his protagonists and for the lack of explicit inclusivity miss the reality of the time that he was writing. The late 50’s were not a time for the writing of the late ’60’s, and the era when he grew up was worse. He still had more strong female characters than many other writers, and some, like Mother Thing, Star, and Pod hold up fairly well as role models. Helen Walker is also a strong female, if only a side character.

Sex in the Heinlein YA books is taboo, as is appropriate by the mores of the 50’s. It wasn’t until the Flintstones in 1960 and the Munsters in ’64 that a married couple were shown in the same bed*. The CCA was very much a thing. The male protagonists in the books had no choice about thinking dirty thoughts on the females, they were required to pure and clueless.

Actually the obscure comedy Mary Kay and Johnny had the couple share a bed in the 1940s. Unfortunately, this was pre-videotape so no episodes survive.

Twenty years ago I saw someone who !ooked familiar in TV. It took some time to figure it out. She reminded me of a friend, who was black. Except the woman in tv was white.

Something about her face or her smile, or gestures reminded me of the woman I knew.

i’ve always taken the Heinlein passage in that way, especially since Carolyn is said to be bigger than his sister.

we shouldn’t erase differences, just embrace them. But too often when we see different people, we see their color primarily, rather than other things that we share in comments. When you get beyond colour or race, you see other things.

I’m surprised nobody has commented about one thing. Heinlein’s juvenike main characters often do seem like sponges, soaking up what a parent figure says. I onky noticed it in recent times.

They are all capable, something I liked. But a father says something, and suddenly they go in that direction, unwilling to question what was said, likely defending the father if anyone criticizes the point of view. Nkt always fathers, but a male figure. Even in “Between Planets” or “Citizen of the Galaxy” the main characters fit into whatever environment they are in. Thorby sees the world as a slave, but then as a free trader, and then as a soldier. Though he never becomes the same way as a rich man.

I had my hobbies as a kid, and it lead me to question the adult world. I picked up small bits of usefulness, but no adult said simething where I immediately changed direction.

Norton was writing at the same time.

In “Citizen”, Thorby would have happily stayed about Sisu…but he had a duty to Pop to do as the Captain asked, carrying out Baslim’s wishes.

This is very exceptional writing. I’ll definitely have to be reading this later