In the lead-up to the 2019 Hugo Awards, we’re taking time to appreciate this year’s novel and short fiction Finalists, and what makes each of them great.

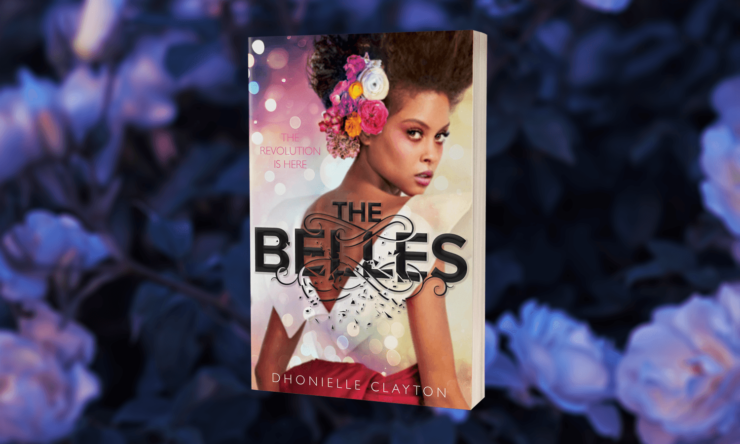

I literally cheered out loud when I heard that Dhonielle Clayton’s The Belles was nominated for a Lodestar Award. What can I say about it to explain my excitement? I could tell you that it’s masterfully written, that the dialogue is pitch perfect and the descriptions evocative. Or I could hype up the fascinating characters and the subtle ways Clayton uses them to explore and shatter tropes. Maybe I’ll talk about how Clayton breaks down how Western beauty standards can be used as both a tool and a weapon, depending on who is dictating the standards and whether or not another person can meet them. Eh, I’ll keep it simple and just say “it’s absolutely amazing.”

When we first meet Camellia, she and her five sisters are about to celebrate their sixteenth birthday. Unlike other girls from the kingdom of Orléans, these sisters are Belles, young women with the magical ability to change the physical appearance of regular people. In reality, the denizens of the kingdom have rough gray skin and coarse gray hair. But with the assistance of the Belles, they are colorful and vivid. Belle magic wears off over time, so only the nobility can afford the perpetual upkeep. The middle class do just enough to look acceptable, while the poor must suffer with their natural state.

All Camellia wants is to be chosen as the Queen’s favorite, but when her sister Amber is selected instead, Camellia is sent to a second-tier salon. With Amber’s sudden and unexpected demotion, Camellia is thrust into the limelight and finds herself under the thumb of Sophia, the sharp-tongued princess eagerly awaiting her chance to claim the throne. The longer she’s in the palace, the more she uncovers about her past and the Belles that came before. Sophia is awful, but the truth about the Belles is even worse. Camellia is enslaved to crown and country, but not for much longer if she has anything to say about it. She’ll need the aid of the taciturn soldier Rémy and her sisters if she has any hope of success.

The Belles starts off as a standard court intrigue-focused YA fantasy. There’s a girl with a special skill, a highly coveted job working in the royal court, a jealous companion-turned-challenger, a handsome young man working for or connected to the royal family, and a cruel antagonist who tries to use the heroine to do her terrible work. Deadly secrets and heartbreaking betrayals abound. The girl will lose everything and will probably have to foment a revolution in order to save the people she cares about. If you’ve read any young adult fantasy in the past decade or so, you’ve definitely read that book more than once. But The Belles isn’t paint-by-numbers and Clayton isn’t cranking out stock plots and characters. It doesn’t take long for Clayton to completely upend everything about this trope. By the time Camellia gets to the palace, it’s clear there’s something deeper and darker at work. It’s not just that Clayton twists a common trope—tons of young adult speculative fiction novels do that—but that she does it in such an exacting and eviscerating way.

The trope is merely the framework. Building out from that is a visceral story about, as she put it in her author’s note, “the commodification of women’s body parts and the media messages we send young people about the value of their exterior selves, what is considered beautiful, and the forces causing those things to shift into disgusting shapes.” In Orléans, beauty is the foundation on which the entire society rests. Specifically, meeting the constantly fluctuating beauty standards set by the extravagantly wealthy. The culture, economy, labor market, customs and traditions, literally everything revolves around and is directly influenced by how the rich define beauty at any given moment. Beauty is everything—what is beautiful, what isn’t, and who decides which is which.

Princess Sophia’s capriciousness with her ever-changing and increasingly dangerous beauty standards aren’t, in fact, all that dissimilar to what we do to ourselves in the real world. Camellia can use magic, whereas we use bleaching creams and whale bone corsets. We inject and extract and shave down and reshape and enhance and cover up and pluck and wax and laser and cut, all to better fit some random rules about beauty. We export those rules to colonies and cultures and force them to comply. We blame ourselves for failing to be as beautiful as we think we should be, and we punish non-compliant women especially. If a group of teenage girls suddenly developed beauty magic here in the real world, I have no doubt those girls would be enslaved to the upper class almost instantly.

And make no mistake, the Belles are enslaved. Clayton doesn’t sugar coat or shy away from this truth. The Belles’ lives are literally built around doling out beauty treatments. They have no hobbies or interests, are disallowed personal lives or meaningful relationships, and cannot leave the salon where they are installed. Their actions are dictated by others, and they cannot refuse. Disobedience is matched with violence and punishment. Camellia and her sisters don’t realize this until they’re out on their own, but once they do, the shiny veneer of being a Belle is harshly washed away. Breaking free is more than just escaping their prisons—easier said than done—and fleeing the kingdom to the unknown lands beyond the sea. If there are no Belles then Orléans itself collapses. They are beauty and beauty is the foundation. A society cannot simply stop slavery without facing the truth of its actions and vowing to do better. But what if Orléans doesn’t want to be better?

When I finished The Belles I was lucky to have a copy of the sequel, The Everlasting Rose, on hand so I didn’t have to let the good times end. Even without its pair, The Belles is a stunning novel. I work in a high school library and this is one of my most frequent recommendations, for reasons I hope I got across here. It’s a brilliant piece of feminist fiction and will surely stand the test of time. And if that doesn’t make The Belles award-worthy then I don’t know what does.

Alex Brown is a high school librarian by day, local historian by night, author and writer by passion, and an ace/aro Black woman all the time. Keep up with her on Twitter and Insta, or follow along with her reading adventures on her blog.

Interesting! I read the first 15 or so pages of this and didn’t think it was going anywhere other than fluffy descriptions of pretty people. Now I’m curious to give it another try.

It’s really unfortunate that Clayton got sick while writing the second book and felt she needed to end the series somewhat abruptly. It could definitely have been a trilogy. Still, they’re an enjoyable read that also explores the harm in western beauty standards and the commodification of women’s bodies.

I’m slightly past halfway through THE BELLES, and the further I get, the more I love it. Does the book have some first-time-author flaws? Sure. But (so far, at least) I think the characters and the world-building and the subtle build of the plot far outweigh the flaws.

At first it was all about the spectacle (and maaaan, I keep imagining the gorgeous yet disturbing movie this would make– eat your heart out, Caesar Flickerman). But then Camille starts interacting with the nobility of Orleans in the course of her job, and you start to see how very deeply cracked things are under that pretty veneer. And then the little dropped hints about the Belles’ secrets (both the ones they hold, and the ones that are kept FROM them) start adding up, and the mystery of what’s REALLY going on in Orleans just sucks you down whole.

I read Clayton’s “Dear Reader” bit at the end before I started the book (I like reading author notes first), and I love how she keeps serving up her “beauty monster” theme in subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) ways throughout the book. There’s one scene in particular… it’s pretty minor, in context, but I can’t get it out of my mind. (And for those who don’t like anything even remotely spoilery, I’m putting my summary of the scene in white, here. Highlight it if you want to know, scroll down if you don’t):

Camille’s mother once told her “the people of Orleans hate the way they look.” On the face of it, you’d think she was talking about the red-eyed, grey-skinned monstrosities that are their natural forms. But the scene where Camille is reminded of her mother’s words suggests something quite different. A beautiful client whose beauty treatment is fading comes to Camille. But instead of a touch-up, she asks for a radical makeover– she wants to be thinner, she wants to be trendier-looking. Camille protests–what about the pain so many treatments will cause? The woman tells her that if she could withstand being rebuilt bones-out, she’d do it. “I’d do anything to be beautiful.” Camille is taken aback, and she thinks of her mother’s words. She tries to get through to her client again, since, in her judgement, the woman is already quite beautiful and needs a touch-up at most, but the woman screams at her: “Stop lying to me… I know what I look like.” (p.199) (But… DOES she?)

The whole scene put me in mind of body dysmorphia, a (real-life) mental disorder in which a person is obsessed with perceived flaws in their appearance which are, in reality, either unremarkable or non-existent. A LOT of (real-life) women struggle with this– I have a friend who came really close to self-harm because of it. Our beauty, fashion, and weight-loss industries encourage it. I suspect the Kingdom of Orleans is CRAWLING with it. And (contrary to what some reviews have said), I don’t feel in the least that Clayton is glorifying it in this book.

I’m starting to think that Camille’s mom understood a LOT more about the way their world works than Camille has yet realized. And, although it seems her mother tried to prepare her, I think that poor, eager-to-impress Camille is in WAAAAAAY over her head. (And I’m really sad to hear there’s not a third book.)