Welcome to Tor.com’s new column on History and SFF!

My name is Erika Harlitz-Kern, and I will be your guide during the coming months in discussing the ways that history is used in fantasy and science fiction. But don’t worry—I won’t be dissecting your favorite story digging for historical inaccuracies and judging its entertainment value based on what I find… The purpose of this column is to take a look at how authors of SFF novels and novellas—with a focus on more recent works, published after the year 2000—use the tools of the trade of historians to tell their stories.

When any scholar does research, they use a set of discipline-specific tools to make sense of their sources and the material and the information they find. Historians are no different. In history, these tools consist of techniques on how to evaluate texts, how to critique the research of other historians, how to think critically about the past, and how to be transparent when presenting research results. This column will delve into how authors use these same tools to tell their stories and build worlds.

One useful example of how an author can utilize the historian’s tools of the trade is Isaac Asimov’s Foundation. The world in Foundation is based on psychohistory, which in the hands of Asimov becomes “the science of human behavior reduced to mathematical equations” because “the individual human being is unpredictable, but the reaction of human mobs […] could be treated statistically. The larger the mob, the greater the accuracy that could be achieved.” In other words, psychohistory is a mathematically calculated direction of societal development based on Big Data and the behavior of macro-level cohorts in the past.

Asimov doesn’t engage in the telling of real-life history, but by including encyclopedia articles that sum up past events and individual lives, he uses historical research techniques as the framework and foundation (sorry not sorry) for his story and the world where it takes place. This approach is what unites the various stories that will be discussed in this column.

So, what topics will this column focus on?

First, we will discus the conundrum of what drives historical change. Within historical research, there is a tension between attributing historical change to the actions of single individuals or to the workings of groups within societal structures. In Asimov’s version of psychohistory, this tension is taken to its extreme. Science fiction is often considered to be a genre that examines what it means to be human, using space and the future as the backdrop. What happens when authors use history as the backdrop instead?

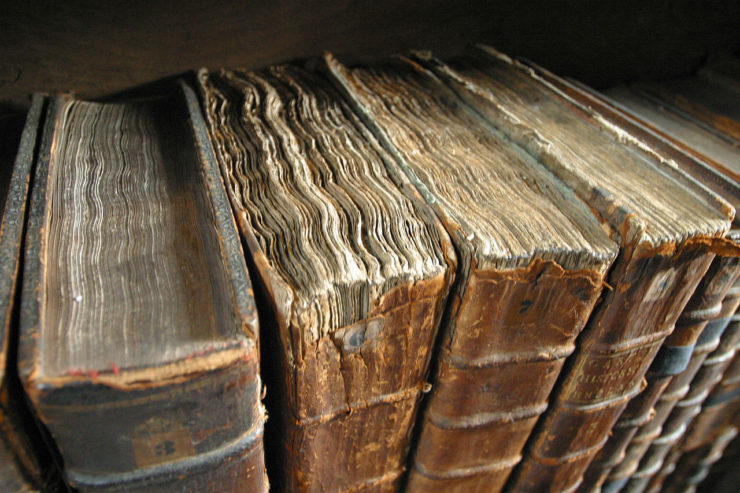

Next, historical documents. Or as historians call them, primary sources. Primary sources are the meat-and-potatoes of historical research. They are the sine qua non of history. They are also a staple in fantasy fiction, where old documents and books are used to either set up the premise of the quest, or to provide backstory. Going forward, we will take a closer look at how authors use these types of sources to tell their stories.

At the opposite end of the spectrum of historical sources is Big Data. Because of digitization, which enables the processing of enormous amounts of information within seconds, Big Data is being touted as something new and the way of the future. As Asimov’s use of psychohistory shows, Big Data is not new to science fiction. Nor is it new to history; historians have been using Big Data since the innovation of the computer punch card. The question is, how do history, Big Data, and SFF interact in the 21st century?

We will also be talking about footnotes: Love them or hate them, footnotes are crucial in demonstrating scientific rigor and transparency. Footnotes can be found in SFF, as well. How do authors use footnotes? Is it to give credibility to their stories? Or is it to mislead?

While we will be covering all of these topics mentioned above, this column will also explore how history is made and how it is used. Because when we talk about history writing and historical research, we are not talking about the past as such; we are talking about an interpretation of the past. It is a fact that the past doesn’t change, but our knowledge of it does. That knowledge is what we call history.

The first topic we will look at here is oral history. Traditionally, historians have studied the human condition primarily through written texts. During the later part of the 20th century, historians began to branch out considerably, looking for information in other areas. Some of them joined cultural anthropologists in studying oral history. Oral history is part of what the United Nations calls “immaterial cultural heritage.” Immaterial cultural heritage is particularly vulnerable, because it’s made up of memories, traditions, and stories passed along by word of mouth. Once the memory of a culture dies, that culture dies too. That can make for compelling storytelling.

The next topic is perhaps the most problematic aspect of history writing—history as propaganda. History developed as an academic research subject at the same time as nationalism developed into a political ideology. Over the century and a half that has passed since then, history has served the interests of nationalism well, providing the development of imperialism and the modern nation state with their own research-based narratives. Much of what we are seeing in the current public debate over history and its interpretation is a questioning of that relationship, and this is certainly reflected in some of the SFF that is being published right now.

Last, but not least, we will talk about alternative history. Alternative history asks the question “what if?” and uses an event in the past to find the answer. This is a great plot device for fiction, but it’s not something historians engage in. Here we will discuss the tension between what was and what might have been, as well as the issues that arise when history is used to predict the future, as seen in the mathematically predicted Seldon Crises of Foundation.

Who am I to set out to cover all these topics? If you haven’t guessed it already, I am a historian and a fan of fantasy and science fiction. I have a PhD in history, and I combine teaching Ancient, Medieval, and Viking history with writing about the genres I love.

Join me next time when I will discuss the driving forces behind historical change in the Tao trilogy by Wesley Chu.

And in the meantime, what other SFF novels and novellas published after the year 2000 would you like to see included in this monthly column? Leave your suggestions in the comments below!

Photo: Tom Murphy VII (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Erika Harlitz-Kern is a freelance writer and historian with a PhD from the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. When not reading and writing about fantasy and science fiction, she teaches history at Florida International University in Miami, and spends her free time in Florida’s wetlands, silently thanking the alligators for not turning her into a snack.

An obvious suggestion is A Memory Called Empire by Arkady Martine. Or The Only Harmless Great Thing by Brooke Bolander. Lent by Jo Walton. The Chronicles or Tornor by Elizabeth Lynn offer a look at how events of a book are remembered as history in subsequent volumes.

I think it would be interesting to look at how authors draw upon historical periods for inspiration and structure, whether Martine’s SF Byzantine Empire or Elizabeth Bear’s “Nongols” in her Eternal Sky trilogy or Guy Gavriel Kay’s books or Lois McMaster Bujold’s World of the Five Gods (especially The Curse of Chalion). How closely do they cleave to our understanding of the those times and places and what changes do they make? Perhaps look at what it means for the great work called history that its products are used in such a way.

Beyond theories of change, there’s also the influence of changing subjects of history. In the bad old days, it was all kings and battles and endless dates. Now historians are more interested in diverse experiences of historical times; what life was like for people who were excluded from written histories or erased from them. We can see this desire to tell difference stories in SFF, I would argue it’s one factor in The Wheel of Time’s infamous verbosity.

No suggestions at this point, just a giant “Yay! Bring it on!”

Is Sarah Gailey’s STET too short a piece for consideration? The interface between social and individual history really hits home in that one.

I expect to see Guy Gavriel Kay’s name a lot.

About footnotes, indeed they can add to exposition and may help the world be more believable, especially in hard SF. However, they can tell their own story or add any kind of nuances to the main story. Like the ones in The Third Policeman.

someone should, perhaps try for an explanation of why so many military histories (or even fantasies) draw on the era of the napoleonic wars, and especially their naval components. These include Weber, but also most of the knock offs in the science fiction/opera category and Novik in the fantasy category (hers is explicit and timely… the space operas, weirder). I suppose one question to be asked is not simply what do writers borrow, but what should we understand about the significance of what they change.

And have changing ideas of military history (eg social history, economic history, etc) changed the space operas/military sfwritten? Maybe williams’ praxis series does this?

I would love to see this approach reflect on Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad or The Nickel Boys. Or Ta-Nahesi Coates The Water Dancer. Or Octavia Butler’s Kindred.

And I’ll echo Guy Gavriel Kay as well.

Bring it on!

As a professional archivist I’m looking forward to being amused!

Also: Florida; come for the ‘gators but stay for the boa constrictors (because one has you in its coils)?

>History developed as an academic research subject at the same time as nationalism developed into a political ideology.

Geoffrey of Monmouth would like a word with you about the Historia Regum Britanniae.

Stories of What We Are and Who We Were have always been closely connected.

PAYING THE PIPER by David Drake (2002)

In the introduction mentioned that the novel’s background was based on Rhodes and Byzantium at the end of the 3rd century BC. Specifically the campaigns of Phillip the Fifth and his allies against the Aetolian League, particularly the campaign of 219 BC which culminated in Phillip’s capture of Psophis.

How do authors use footnotes?

Well, Terry Pratchett used them mainly to make jokes.

@10 – Agreed that the writing of histories to establish priority in land occupation, or to legitimize a new dynasty, is not new. I was appalled to be told, a few years ago, that some Icelandic sagas had been re-written more than once in order to validate land ownership claims. but then it was an Icelander that told me this, and perhaps he was trying to undermine the validity of Icelandic sagas to support land claims of his own.

A question for the author, however – Tony Zbaraschuk points out that politically-slanted histories go way back, but what about those more general histories that seem to be written as narrative accounts of events? I’m thinking of Herodotus and Thucydides in particular, but isn’t that a possible class of histories – written in as unbiased way as possible, subject to the judgement of the writer, as an effort to present the way that things had gone?

This is a delight to find on Tor.com. Thanks for taking it on.

I’m really looking forward to these articles.

Connie Willis, Doomsday Book; also Blackout/All Clear. At least.

For the alternate history, an interesting comparison could be made between Steven Barnes’ Insh’Allah novels, Lion’s Blood (2002) and Zulu Heart (2003), and the more popular The Years of Rice and Salt (2002) by Kim Stanley Robinson.

Both works are alternate history set in a world where the population of Europe died off due to the Bubonic Plague. Barnes and Robinson are American, both were born in 1952, have lived in California most of their lives, and have been writing SF since the late 70s. Barnes is black; Robinson is white.

A look into their historical differences would be illuminating.

@12 “Of course I have a right to this pasture, why would the skalds be singing about my great-grandfather fighting off wolves in it?”

Rule #1: never trust the bard.

I just adore footnotes!

I just adore footnotes!

Sounds fascinating. Of course I suppose I should mention I have a BA in History.

How about Martin’s use of the War of the Roses? I see it thrown around but never explained.

As near as I can tell Martin took the Cousin’s War and dialed it up to nine. More sides, more devestation, lots of murder and rapine.

@20 And then there were zombies and dragons. No wonder the show botched the transition from historical fiction to epic fantasy.

I found Asimov’s Foundation insufferable, even beyond the utter impossibility of predicting issues like how fast a nonexistent culture will deplete resources it hasn’t found yet. An empire can last for fifty thousand years without its women ever getting the idea that they merit equal rights and ability to use their talents? Reeeaally?

I would love to see an article about the excellent Queen’s Thief series by Megan Whalen Turner (book 1 was published in 1996, but the rest are all after 2000, so hopefully that works).

Other books that would be interesting:

Mistborn series by Brandon Sanderson (either Era 1 or Era 2, both seem they would contribute).

Or The Emperor’s Soul, also by Sanderson, seems very on topic.

Wheel of Time could also be fun, but very not 2000s.

Eifelheim by Michael Flynn seems like an obvious candidate here.

Even though Robert Heinlein’s writing predates 2000, I would like to suggest his future history series of short stories and novels for your attention. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Future_History_(Heinlein)

Samuel Delany’s Neveryon series would fit, even if they are outside the proposed time range. First, they are an exploration of late prehistory, showing how it relates to the present time. They manage to make ancient days seem modern by showing how, even in those forgotten times, new things appear, events from a few years ago can seem ancient, and fads and fashions rise and fall.

But it is also framed as a story of historical research, with fictional (?) scholars and primary sources.

@23 It was finished in 2013. It totally counts. Who wouldn’t want to read 4 million words for a column?

Although her publishing history is outside your stated range – late 80s to early 90s – Susan Shwartz’s name immediately came to mind as I read your description. Also, despite her inclination to write humor, Esther Friesner has some interesting books in that time period.

I’m very excited about this!

How about S.M Sterling’s series – Nantucket? While I haven’t read this one myself, throwing modern people into a past so foreign to them would be another way to see history in action.

Authors who come to mind when it comes to history turning on a pivot (or that big watershed moment) are Eric Flint and Harry Turtledove.

The one thing I have always been taught: “history is written by the winner”. I think propaganda has been there since we had history to pass on. Some of it was changed to sway opinions or provide excuses for what was done. I think even more may have been altered because a bard or storteller needed a better ending or to simplify events to keep audience attention. Now days we do it with movies.

The thing that has always bothered me is the way we cleanse our heros. The real person maybe whored around or treated people like dirt but did the right thing in battle. Jump ahead 100 years and he practically walked on water, never had self doubts and was handsome to boot. Seriously, how tall was napolean?

For a book there is the 2nd book in Deboroh Harkness’ Discovery of Witches that jumps back to Tudor England.

Anubis gates

@31, people who believe victors write the histories are unacquainted with the vast body of literature produced by the leadership of the Lost Cause.

An expansive example of Alt History is Eric Flint’s 1632 series. I have not been able to keep up with the series, but the first few books that I read did a good look at transferring technology and “gearing down” to what is capable.

@11 – Many of David Drake’s stories are developed from ancient Greek & Roman history. Look at his RCN series for other examples.

@6 – I think the Napoleonic wars lend themselves to science fiction/fantasy so well is due to it being well documented in English.

@@@@@ 34, mtumoose:

Many of David Drake’s stories are developed from ancient Greek & Roman history. Look at his RCN series for other examples.

It comes of his being a Latin scholar. That whole series bases the Cinnabar Navy—with its external rigging—on the Napoleonic era British Navy, but In Spaaaace.

Here are his notes about the 2006 Some Golden Harbor.

I’ve based the setting of Some Golden Harbor on political and military events taking place during the early fifth century BC in Southern Italy (Aricia, Cumae, and the Etruscan federation). All right, that’s a little obscure even for me, but I found the discussion of Aristodemus of Cumae in an aside by Dionysius of Halicarnassus to be an extremely clear account of the rise and eventual fall of an ancient tyrant.

There’s more real information here than in the lengthy, tendentious, and generally rhetorical disquisitions on Coriolanus (a near contemporary, by the way). I suspect that’s because Aristodemus is unimportant except as a footnote to Roman history, whereas Gaius Marcius Coriolanus provided one of the basic myths of Rome. The real Coriolanus and the real events involving him are buried under a structure of invention, but nobody had a reason to do that in regard to Aristodemus.

While the basic politico-military situation comes from ancient history, I took most of the business on Dunbar’s World from the South during the American Civil War and the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War. I’ve enormously simplified what went on in both cases.

Every time I really dig into a period I learn that what a secondary history gave two lines to was an incredibly complex business that could’ve as easily gone the other way. I’m pleased when I meet people who know any history at all, but I do wish that people who’ve read only secondary sources (or worse, have watched a TV show on the subject) would keep in mind that there’s a lot beneath the surface of any major historical event. I want to scream every time I hear someone say something along the lines of, “What really caused the Roman Civil War was—”

No, it didn’t. Nothing that complicated has a single, simple causation. When somebody frames his statement in those terms (those doing so have invariably been male in my experience), he proves that he doesn’t know enough to discuss the subject.

I will be following this with great interest.

Book suggestions:

Alternate history: Most (all?) of Mary Robinette Kowal’s books qualify, from her Glamourist histories (fantasy set in Regency-era England and Europe, with an Austenesque flavor) to her WWI fantasy, Ghost Talkers, to 2018’s Lady Astronaut series (The Calculating Stars and The Fated Sky.) I would love to see any or all of these discussed in this column.

Alternate history: You’ve already mentioned Novik’s Temeraire series. Yes, please!

Historical documents: The plot of Deborah Harkness’s All Souls Trilogy revolves around the missing (and magical) manuscript, Ashmole 782. There really was an Ashmole 782, and that’s all that is known about it; we don’t know its title, author, or contents…which makes it perfect for Harkness’s purpose. But Harkness (a historian and scholar herself) also mentions other books and manuscripts throughout the series. Plus, book two takes place in 16th-century England, France, and Prague, as the protagonists travel back in time, so it plays with history and historical figures in that way as well.

Historical documents AND sort-of-alternate-history: A Natural History of Dragons (Marie Brennan) is both the title of a “memoir” by “Lady Trent,” a 19th-century naturalist from a country clearly based on Great Britain, and the book which causes the child Isabella (later Lady Trent) to become captivated by dragons in the first place.

The only history American authors seem to use is their civil war and maybe their first presidents. Don’t American readers get bored by that?

“His Majesty’s Dragon” by Naomi Novik.

@37: Respectfully: Plenty of American authors have drawn on other periods of history than the Civil War and the founding fathers/Revolutionary War era. Have you read:

Mercedes Lackey’s Elemental Masters series, set mostly in Victorian, Edwardian, and WWI-era England

Mercedes Lackey & Roberta Gellis’s Elizabethan fantasy series (on my TBR)

Mary Robinette Kowal’s fantasy and sci-fi (see my comment #36 above)

Naomi Novik’s Napoleonic-Wars-with-dragons series (the Temeraire books)

Katherine Kurtz’s Deryni novels, clearly based on medieval and early Renaissance Britain and Europe

Sarah Gailey’s hippo-wrangler series (on my TBR)

Jim Butcher’s Codex Alera series (loosely based on the Roman Empire; I haven’t read them yet)

David Eddings’ Elenium trilogy is loosely based on medieval Europe, and his Elene church and militant orders are strongly reminiscent of the Crusader-era Catholic Church

Randall Garrett’s Lord Darcy series is set in a late-1800s Plantagenet Empire in which Richard the Lionheart had lived and founded a dynasty

Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, in which the Axis powers won WWII (on my TBR)

William Gibson and Bruce Sterling’s The Difference Engine, in which Babbage’s invention is developed into a working computer (on my TBR)

Vonda McIntyre’s The Moon and the Sun, set in Louis XIV’s court (on my TBR)

… and those are just for starters.

@37 Even Turtledove who’s a bit of a poster boy for post-Civil War alt-history, probably has more books based on WW2 alt history than ones where the split point is the Civil War.

@@@@@ 37, birgit:

The only history American authors seem to use is their civil war and maybe their first presidents. Don’t American readers get bored by that?

Robert Conroy wrote many alternate histories.

Liberty, 1784 is set in the American Revolution

Two were set in the American Civil War:

1862 has Great Brittan entering on the side of the Confederates.

The Day after Gettysburg has Lee recovering and going on the offensive.

Three are set interbellum.

1882, Custer in Chains has Custer surviving the Little Big Horn, becoming president, and declaring war on Spain

1901 has Kaiser William’s Germany attacking McKinley’s America

1920 America’s Great War has Kaiser Bill’s Germany winning WWI and attacking America

Seven are set in WWII

1945,

1942,

Red Inferno,

Himmler’s War,

Rising Sun,

North Reich,

Germanica

I’m going to enjoy this column . I second Novik, Turtledove, and Robinette Kowal.

Let’s not forget Turtledove’s monetizing of his doctorate in Byzantine history (and his cruel use of Latin to insert the phrase Maxwell’s Silver Hammer in one of his books).

As for footnotes, Pratchett is the hands-down winner, though I will always love the ones in Pangborn’s DAVY.

Stirling is currently doing an AU of Teddy Roosevelt, Rampant, though I haven’t read them yet.

H Beam Piper has a string of alternate histories in his Paratime series.

In S. M. Stirling’s The Peshawar Lancers, nineteenth century comet strikes devastate the northern hemisphere. What remains of the British Empire is centered in India. (Athelstane King and Yasmini are borrowed whole cloth from Talbot Mundy’s King of the Khyber Rifles.)

Stirling’s Conquistador is set in a universe where Alexander the Great lived to a ripe old age.

Poul Anderson’s Time Patrol stories has time bandits create several alternate histories, for Manse Everard to put right.

Harry Turtledove’s Ruled Britannia has the Spanish Armada conquering England.

Thread drift is inevitable so it’s nice that it’s also usually interesting.

Still given an explicit intent to discuss the tools of historians

– The purpose of this column is to take a look at how authors of SFF novels and novellas—with a focus on more recent works, published after the year 2000—use the tools of the trade of historians to tell their stories.

most of the discussion has been I think about folks using the tools of authors of SFF novels and novellas to interpret history or alternate history to illuminate history.

Published mostly well before the year 2000, John Dalmas (pseudonym) had a standard Con speech about working with librarians to write realistically. That is to source his stories in reality by using historical analogs for alternate futures. Dalmas set The General’s President in his own future while extensively researching the Great Depression with its alternate tales of FDR saved us and FDR made it worse. With the passage of time it’s alternate history just as much of Pournelle has been overtaken by events. Sadly such works as A Step Further Out are even more alternate.

Carolyn Cherry went into great length in person and on the web to discuss the real world history (in all its changing perspective. Historiography owes the USSR a great debt for teaching examples: Stalin won the Great Patriotic War or maybe the people won the Great Patriotic War or maybe Khrushchev gets credit for Stalingrad? though like Mr. Drake, Ms. Cherry tends to mine Rome and its neighbors) she once taught in schools and brought to her writing.

I’d say Mr. Drake not only uses his remarkable knowledge and understanding of history and culture but also uses a tool not just of writers but equally of historians when he incorporates actual popular songs to illuminate and perhaps add richness to his tales.

I’ve seen what purported to be real history books from academic presses discussing long ago elections and popular campaign songs in context just as the contemporary songs have illustrated actual military campaigns. For a footnote see Drake using Morgan Rot and the discussion of Willy Ley as I recall singing Schubert’s Die Bieden Grenadiere

This is going to be very interesting!! A few books that come to mind right off the bat are Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves (though I’m not sure if it’s quite within the purview of this project genre-wise?), Honor Among Thieves by Ann Aguirre and Rachel Caine,and Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2312.

Bujold has been mentioned, but in terms of using tools of the trade, I’d also be interested in her Sharing Knife books, which clearly are based on real history of trips on the Mississippi. Her use of oral history within the Sharing Knife world is also intriguing.

Second the suggestions to look at Novik and Kowal. :)

#47 -The Sharing Knife books are based on real history of the Ohio River..

I think there is a tendency in history and certainly in oral history to misattribute to bigger more recognizable names. As lesser lights fade with distance – and from a distance so skilled but foreign a researcher as Jo Walton might confuse the Ohio and the Mississippi in Jo’s own comments on Sharing Knife q.v. – what is remembered goes with the greater lights. CF legends in Liberty Valence.

One of the tools of history is a little research. So far as I know Jacque Barzun wrote the definitive work, no longer modern but ever green in The Modern Researcher? Any suggestions for a more recent listing of tools?

The Louisiana Purchase was the outcome of an attempt to acquire New Orleans to give the young United States a port on the Gulf to service the inland territory. Before the Louisiana Purchase the rivers draining what was then the Western United States carried a lot of traffic. Marietta Ohio launched ocean going ships. A few search terms for use on this board are pretty obvious and will be rewarded.

Rippa. Just reading Fallada’s essays and his statement how we must focus not on the criminal ends which glorify history as seen merely from a nation-race point of view is imperative. Given how much sci-fi is stuck in StarWreck fracnchise glory of endless wars proliferates the need to look at history is a great perspective to broaden our horizons