Books are a curious paradox. They are, at once, both story and object. And one of the most compelling bits of paratextual1 material that confronts and engages with this conundrum is the footnote. Other paratextual materials can be more easily separated from the story or even ignored. There’s an old cliché about not judging a book by its cover, and the maps and illustrations in classic fantasy novels are often so expected they don’t always register as a way of guiding you, the reader, through the book.

Like maps, illustrations, and covers, footnotes frame the text. They also pause it. They offer a chance to step back from the narrative and dispute it, observe it, or explain it. Footnotes aren’t often found in fantasy, and because a footnote’s natural habitat is the academic text, footnotes bring with them implications of scholarly rigor, a sense of painstaking objectivity, or carefully grounded and continuing arguments in The Academy.

Jenn Lyons’s The Ruin of Kings takes the implications of the footnote seriously, and uses them to confer authority on the compiler of the various bits of evidence, thus inviting the reader to agree with his findings. In-world compiler and royal servant, Thurvishar D’Lorus, introduces the book as “a full accounting of the events that led up to the Burning of the Capital,” based on transcripts and eyewitness accounts, the footnotes being D’Lorus’s “observations and analysis.”2 The very acts of explanation and analysis confer authority. The footnotes position D’Lorus as an authority whom the reader is invited to believe. It also lends an air of authenticity to the bundled set of “documents,” suggesting, via their presentation, that they are impartially but carefully gathered evidence, and positioning the reader as a judge and active participant in the proceedings.

Buy the Book

The Ruin of Kings

Jonathan Stroud’s Bartimaeus Sequence also explores the implications of authority inherent in footnotes (and endnotes, depending on the edition), but turns it on its head by keeping the footnotes to the first-person sections narrated by Bartimaeus, a five thousand year old djinni3. In a front note for the GoogleBooks edition of The Golem’s Eye, Stroud makes his purpose in including footnotes explicit: “Bartimaeus is famous for making snarky asides and boastful claims, which you can find in this book’s endnotes.”4 The marginalized first-person narrator reflects the power structure of Stroud’s alternate world London, where humans work magic by using “the right words, the actions, and most of all the right name”5 to trap spirits like Bartimaeus to do their bidding. Via footnote, Bartimaeus reasserts his personality and authority in a narrative that begins with his entrapment and enslavement to Nathaniel.

Buy the Book

The Golem’s Eye

Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell seems like a similarly straightforward example… at first. In her merged world of Regency England and Faerie, the practice of magic has fallen aside in favor of the academic study of magic. The novel itself purports to be part of this tradition, citing magical texts that exist only in the world of the book, in an attempt at verisimilitude that later becomes subversive. Several footnotes contain hidden Faerie stories unknown to any of the characters, or the other scholarly works previously cited, and, in fact, dispute the story filling up the body of the page.

The omniscient narrator compiling all this information is never named, but the footnotes begin to seem more like the real story. On certain pages, the footnotes take up more space than the narrative, just as the minor characters begin to take up greater and more important positions within the plot. The Gentleman with the Thistledown Hair, the main antagonist, is not defeated by the titular Strange or Norell, but by Stephen Black the butler. This shift in focus, on the page and in the narrative, asks the reader: what stories, and what people, are being marginalized by the master narrative? Who gets to occupy the page? What have you missed by not looking deeper, or by looking at those traditional fantasy, or traditional history, ignores?

Buy the Book

Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell

Sir Terry Pratchett, perhaps the most famous footnoter in fantasy, is also deeply concerned by these questions of who gets to be in a story and who gets to tell it. But his interest isn’t just in interworld commentary, but a deliberate engagement of our world. A first reading might suggest that he wields footnotes as worldbuilding, providing information or jokes that might otherwise slow down the plot. But his footnotes weave an elaborate network of literary allusions that asks the reader to think critically about how other books inform the one they are currently reading.

In one footnote for a nonsense academic posting as a reader of Invisible Writings, Pratchett does all three of these things very neatly. He explains how academia works on the Disc, makes a joke on esoteric subject matter in academia, and offers a clever definition of intertextuality, which can be “boil[ed] down to the fact that all books, everywhere, affect all other books.”6 This explanation is a key insight into Pratchett’s authorial approach. He writes fantasy books about other fantasy books. His footnotes situate his works within the genre and tell the reader: pay attention. The tropes he is turning inside out and upside down (and shaking until all the jokes fall out of their pockets) exist within a web of other tropes. What is it you know about elves, or Santa, or gender, and where did you learn them? What other narratives have you been taught and who told them to you? Most importantly: why do you believe them?

Buy the Book

Lords and Ladies

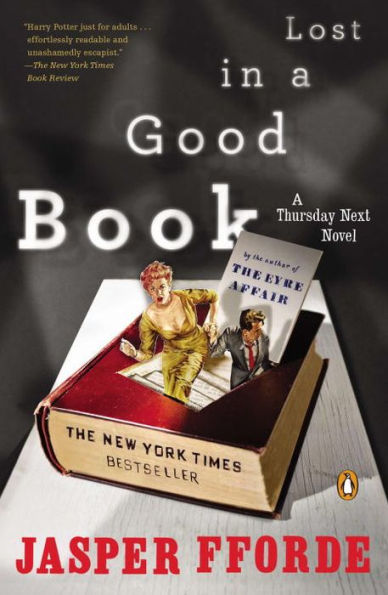

In the metafictional Thursday Next series by Jasper Fforde, this questioning of the text takes a turn for the literal. In Lost in a Good Book, the second in the series, Next’s usual method of entering into literary worlds is destroyed, and Mrs. Nakajima teaches her the art of “bookjumping,” where one can read one’s way into a book. Next doesn’t just passively lose herself in the story. She becomes an active participant, continuing her work as a literary detective.

The dedicated detectives who investigate crimes against and within literature are members of an elite squad known as the Jurisfiction7 . One of their main communication tools is the “footnoterphone,” where a character speaks on the page, and gets a response from another in the footnotes. It’s a clever mise-en-abime of the Thursday Next series itself, as Next spends the series moving in and out of fictional worlds and talking with some of the most famous characters in the Western literary canon. She is literally in dialogue with and commenting on the actions of Miss Havisham or the Jane Eyre, questioning their choices and changing the plots of their novels. It portrays a character actively engaging with a text: forging personal connections with it, questioning it, and investigating just how and why a story is the way it is. (Next’s later visit, in book six, to FanFiction Island, also suggests another method of active engagement with a text.)

Buy the Book

Lost in a Good Book

Though footnotes may seem like an academic affectation that distances the reader by calling attention to the book as an object, rather than a narrative in which you can unthinkingly immerse yourself, they can, in fact, heighten our understanding of, and engagement with, the story. They signal that there is more to this world and this story than is in the narrative. They lift up the hood of the text block to show you the mechanics of the world— the rules of magic, or the previous experiences of a narrator-— as well as the mechanics of book production. They ask: who made this book for you? Was it a helpful in-world collator, with their own agenda? Is it some mysterious, otherworldly force who knows the real story is actually in the margins? Is it an omnipotent author trying to engage you in a specific conversation? They ask: where did this book come from? What documents, or books, or life experiences is the in-world scribe drawing from? What other books is the narrator talking to, when writing this one?

Footnotes are the flag of continued conversation: between author and novel, between characters, between narrator and reader, between narrator and narrative, between book and other books, and most of all, between book and reader.

Elyse Martin is a Chinese-American Smith College graduate who lives in Washington DC with her husband and two cats. She writes reviews for Publisher’s Weekly, and her essays and humor pieces have appeared in The Toast, Electric Literature, Perspectives on History, The Bias, Entropy Magazine, and Smithsonian Magazine. She spends most of her time writing and making atrocious puns—sometimes simultaneously—and tweets @champs_elyse. She’s at work on several novels.

[1]From, fittingly enough, the paratextual jacket copy of literary theorist Gérard Genette’s classic 1997 work, Paratexts: thresholds of interpretation, paratexts “are those liminal devices and conventions, both within and outside the book, that form part of the complex mediation between book, author, publisher, and reader: titles, forewords, epigraphs, and publishers' jacket copy.”

[2]Jenn Lyons, The Ruin of Kings (New York: Macmillan, 2019).

[3]Interestingly, when Nathaniel is the point-of-view character, the story is presented from a third-person limited perspective.

[4] Jonathan Stroud, The Golem’s Eye (New York: Hyperion, 2004).

[5]Jonathan Stroud, The Amulet of Samarkand (New York: Hyperion, 2003), 5.

[6]Terry Pratchett, Lords and Ladies (New York: HarperCollins, 2002), 49.

[7]These are their stories. Dun-DUN! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gP3MuUTmXNk

You forgot Jack Vance, king of footnotes

My favorite footnotes in fantasy are Peter Dickinson’s footnotes in the short story “Flight” (Imaginary Lands, Robin McKinley, ed.). It’s a sad story, and I would never have re-read it if not for the footnotes, but the footnotes bring me back. By the way, if you read it, I believe the footnote asterisk on page 68 is misplaced: it should be after the last full paragraph (The Secret Glory), not the paragraph above it.

I’m a bit — but only a bit — surprised that Swift and his contemporaries got no footnote love here. It’s impossible to read “A Tale of a Tub,” “The Battle of the Books…,” or many other works (not just Swift!) from the immediate post-Augustan period without engaging with the footnotes and their shadowy breach of what we now call the fourth wall.

Really entertaining.

I recall Harvard Lampoon – Bored of the Rings emulating Tolkien’s footnotes with the reference “Either Arglebargle IV or somebody else”.

Nothing destroys immediacy more than a bunch of footnotes. Not really a fan of them for that reason and that some authors can’t avoid the “look how clever I am” snark in them.

Shoutout to Brandon Sanderson’s “Allomancer Jak and the Pits of Eltania” , or as I call it, “Mistborn Science Theater” . The main text is a pulpy 20’s-style gentleman adventurer story, with savage natives, a Faithful Ethnic Sidekick, and beautiful love-interest-in-distress. The footnotes are by the aforementioned “faithful” Ethnic Sidekick, as commentary on an in-world volume; his thoughts on his boss’s intelligence, literacy, and general narrative reliability are constant and delightfully snarky.

What, no one’s only one mentioned of Tolkein yet? LoTR is full of footnotes. (And appendices, forewords, and other literary detritus.)

Michael Crichton’s “Eaters of the Dead” has fun with foot and end notes.

necessary_eagle @6, this, and speaking of end-/footnotes and Brandon, I can never forget Alcatraz’s use of them in “Alcatraz vs. the Shattered Lens”.

I have not met many end- or footnotes during the last decades, but they were very common in the translated books I read as a kid and I loved them for they often gave me insight and deeper understanding to things and contexts I would not have known otherwise. It is true, though, that they somewhat ruin the immediacy.

My favorite footnote of all time is from Good Omens.

“…Hair Today,* the hairdressers’ on the High Street…”

“*Formerly A Cut Above the Rest, formerly Mane Attraction, formerly Curl Up and Dye, formerly A Snip at the Price, formerly Mister Brian’s Art-de-Coiffeur, formerly Robinson the Barber’s, formerly Fone-A-Car Taxis.”

And yeah, it may not be the strongest joke ever, but Curl Up and Dye made me laugh for a solid minute.

@7 Wiredog LOTR is famous (or infamous, depending on how you think of such things) for its appendices, (I happen to like them when they’re well done) but I don’t recall footnotes as such.

I agree about Eaters of the Dead. I love the framework of the novel as an annotated translation of a historical document…which it even sort of is, as the protagonist Ibn Fadlan was quite real and his observations of Viking culture are incorporated verbatim into the text.

On the broader related subject of metafictional techniques in fantasy, two examples leap to my mind: (1) The Princess Bride, presenting itself as the condensed “good parts” version of a classic Florinese novel. (I was completely suckered by this framing device when I first read it at age 16.) (2) The Khaavren Romances by Steven Brust, which pretend to be the work of history by an eccentric, opinionated and, one gathers, not entirely reliable historian.

I recall Harvard Lampoon – Bored of the Rings emulating Tolkien’s footnotes with the reference “Either Arglebargle IV or somebody else”.

Lord of the Rings has no footnotes. Neither does JK Rowling, though, as David Langford points out,

Actually I think it may have one footnote, clarifying that March has 30 days not 31 in the Shire calendar.

ajay@11,12

There are several footnotes in the main text of LOTR. I’ve spotted four in a quick check (in the “At the Sign of the Prancing Pony chapter noting that Elves refer to the Sun as female, near the end of the “Strider” chapter noting that “The Sickle” is the Hobbit name for the Great Bear constellation, in the “Lothlorien” chapter referring to a note in Appendix F, and in “The Scouring of the Shire” chapter noting that the nickname “Sharkey” was probably Orkish in origin).

The Appendices, of course, have LOTS of footnotes.

In Jeff VanderMeer’s City of Saints and Madmen, specifically The Hoegbotton Guide to the Early History of Ambergris, by Duncan Shriek the many many footnotes add an extram layer of whimsy to this already odd, whimsical pseudo history.

House of Leaves doesn’t rate a mention?

I love footnoted fiction! And Jim McDoniel’s An Unattractive Vampire is a hilarious example.

I just adore footnotes. It must be my academic bias.

Hah, I love footnotes and how they give the work a feel of authenticity (such as Tolkien’s extensive appendices and footnotes and liguistic ruminations). Smebody already beat me to my favorite use of footnotes which is Sanderson’s Alcatraz series. I know I was laughing out loud on the bus while reading those. I can’t remember if this is from a footnote or not, but there’s a part where the narrator remarks that Shasta killed Asmodean and I burst out laughing during my bus commute.

Should “affection” in the first line of the second-to-last paragraph be “affectation”?

@19 – Yes! Fixed, thank you.

Borges.

I think you mean “omniscient narrator” – not “omnipotent” (twice).