Stop me if you’ve heard this before: A United Planets starship manned (we’ll get back to that) by an elite crew, on a multi-year mission at the borders of explored space, arrives at a seemingly desolate planet. They very quickly discover the planet is not quite as desolate as it seems; there’s something there that may endanger the ship.

Sounds like an episode of the week for Paramount’s beloved SF television franchise. Nope! It’s…

Forbidden Planet

Written by Cyril Hume (story by Irving Block & Allen Adler)

Directed by Fred M. Wilcox

Produced by Nicholas Nayfack

Original release date: March 3, 1956

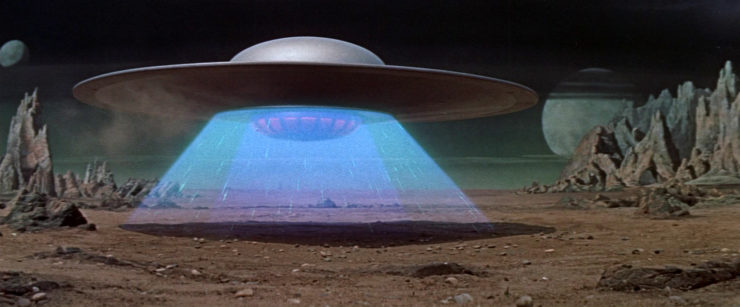

United Planets cruiser C-57D, under the command of Commander John J. Adams (Leslie Nielsen), was dispatched to Altair IV to find out what had happened to an expedition that had been sent out twenty years earlier. As soon as the starship arrives in orbit, C-57D receives a transmission from the surface. There is at least one survivor of the earlier mission. To Adams’ surprise, the survivor, scientist Dr. Edward Morbius (Walter Pidgeon) doesn’t want to be rescued. Indeed, he warns the craft to go away if it wants to save its crew.

Adams’ orders don’t permit him to simply turn around and go home empty-handed. C-57D touches down on the surface of the alien world and sets to work setting up an interstellar communicator with enough range to reach Earth, sixteen light years away. Adams needs to consult HQ: what to do about Morbius?

Once on-planet, several crewmembers die.

Buy the Book

To Sleep in a Sea of Stars

Morbius grudgingly reveals to Adams and his dwindling crew that two hundred thousand years ago Altair IV was home to the Krell civilization. The Krell were far more advanced than humans and yet they mysteriously vanished overnight, for reasons unknown. Only their artifacts remain to show that they existed.

Except…something watches over the planet, an entity that takes a close and sometimes deadly interest in visitors. Most members of Morbius’ expedition (save for Morbius and his wife) died as the guardian hunted them down one by one. The remainder died when their starship exploded as it attempted to leave Altair IV.

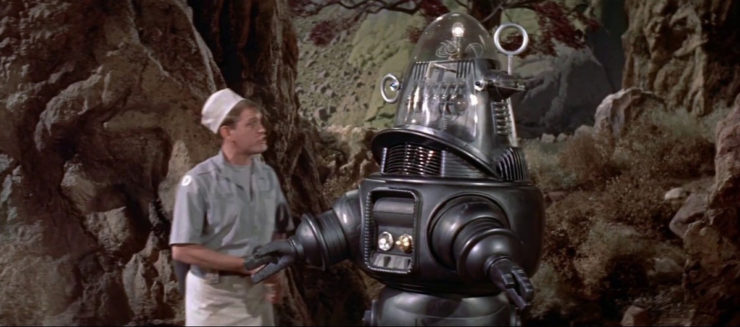

In the twenty years since then, Morbius has devoted himself to studying the Krell relicts. He has but two companions: his beautiful daughter Altaira (Anne Francis) and Robby the Robot (stuntman Frankie Darro, voice actor Marvin Miller). Robby is years beyond anything Earth can produce (his deadpan snark is exquisite). Curiously Morbius claims to have built Robby himself, an achievement that appears to be well outside the skillset of a scientist whose specific field is philology.

The Krell may be long gone (save, perhaps, for the guardian) but their machines live. It takes Morbius some time to overcome his reluctance to share what he knows, but eventually he reveals that mile after mile of vast and powerful Krell machinery exist deep beneath Altair IV’s crust. Each of those machines still functions. One of the devices boosted Morbius’ intelligence, which is how he was able to create Robby and why he doubts that anyone else could grasp the Krell secrets.

Just as Morbius feared, the guardian reappears. At first the unseen entity settles for sabotage. When Adams takes steps to confound the guardian, it escalates, murdering any crewman who gets in its way. It remains invisible save when it tries to force its way through the energy barrier around the camp. The barrier that should have disintegrated it on the spot merely illuminates it with an eerie glow.

[Spoilers follow. You have been warned.]

Lt. “Doc” Ostrow (Warren Stevens) duplicates Morbius’ feat and submits to the Krell intelligence amplification device. The side effects are lethal, but before Ostrow dies, he reveals the mystery of the Krell extinction. The Krell had created a device that can turn conscious wishes into reality. What they did not anticipate was that it would also turn their darkest subconscious yearnings and hatreds into reality. The device created monsters, Id monsters that killed the Krell.

The Krell are long gone; they cannot have called the guardian into being. It seems that the guilty party is none other than Morbius himself. Whenever he is frustrated in his designs by others, the guardian appears to remove the impediment. The crew of the C-57D are one such impediment, and so too is his daughter Altaira, who has formed an attachment to a crewman.

Only when the guardian is on the verge of killing Captain Adams and Altaira does Morbius allow himself to be convinced of his guilt. He dispels his creature with an effort that leaves him fatally harmed. Rather conveniently, the room in which Adams, Altaira, and Morbius make their last stand happens to contain a planetary self-destruct button.1 Morbius dies after it is activated, leaving Adams, Altaira, and the surviving crew members of the C-57D barely enough time to flee to a safe distance before Altair IV explodes, taking the deadly Krell secrets with it.

This movie clearly influenced Gene Roddenberry2, (though there are as many differences as similarities). Adams may get the girl but not through any particular effort on his part; lacking Pike’s self-doubt and Kirk’s womanizing ways, he’s too much of a straight arrow to get easily distracted from his orders (which may surprise viewers who are more familiar with Nielsen from his comedic acting days). C-57D is much smaller than the Enterprise3 and its crew is much smaller as well. Not that it prevents Adams from losing subordinates at a pace that would make Kirk blush. The ship is FTL capable, but at speeds low enough that you couldn’t turn Forbidden Planet into a planet-of-the-week show. The only aliens on the show are long dead.

One might expect the special effects in a sixty-four-year-old movie would be pretty creaky, but aside from the rather clunky design for Robby (but then again, he was designed by a philologist), and the huge-to-modern-eyes communications gear, the effects stood up pretty well when I first saw this in 1977 and they stand up well now. Part of the reason they do work? Budget constraints; the effects that required expensive post-production work were limited to a few memorable scenes. Had the guardian been visible throughout the whole movie, it might have seemed risible. Viewers can imagine a convincing invisible creature. We get to see an epic expanse of Krell machinery, but only briefly—no time to scoff at das blinkenlights.

The film does show its age in its pervasive sexism. There are no women in the C-57D crew. Aware that his crew of “competitively selected super-perfect physical specimens”4 haven’t seen a woman for 378 days, Adams is concerned that they might behave improperly (for Motion Pictures Production Code versions of improperly5). He has good reason to worry about his men, but not about Altaira, who is unimpressed with crewman Farman’s kissing prowess.

[Farman and Altaira kiss]

Altaira: Is that all there is to it?

Farman: Well, you’ve sort of got to stick with it.

Altaira: Just once more, do you mind?

Farman: Not at all.

[They kiss]

Altaira: There must be something seriously the matter with me…because I haven’t noticed the least bit of stimulation.

It’s probably a mercy that Farman is killed by the guardian soon after.

Egregious 1950s sexism aside, Forbidden Planet works as pure entertainment. It’s a great whodunnit. It even hews to a classic mystery trope: the film drops clues here and there, clues that will lead to the reader (or viewer, in this case) saying at the end “well d’oh, I should have known.” No surprise that the movie is widely held to be a SF film classic.

You can see it online for $2.99 (at several sites).

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He was a finalist for the 2019 Best Fan Writer Hugo Award, is one of four candidates for the 2020 Down Under Fan Fund, and is surprisingly flammable.

[1]Perhaps it’s not entirely coincidental that Morbius, being in command of a device that can make any of his desires real, had a planetary self-destruct device at hand the moment he wanted one. One wonders if his daughter Altaira was also dreamed into being after his wife died.

[2]There are a fair number of parallels between “Forbidden Planet” and the first “Star Trek” pilot, “The Cage.” In fact, the basic plot—planets filled with dangerous relics and nigh-godlike aliens—was fairly common in the series.

[3]The C-57D has awful ergonomics. Partly because it’s disc-shaped, which means there are hard to exploit volumes. Partly because what space there is, is inefficiently used. Modern viewers may find it curious that view-screen controls are inconveniently placed; it’s hard to see the screen while one is adjusting the controls. This was standard TV design back in the day.

[4]Which raises the question of the matter of Earl Holliman’s character, Cook. Cook clearly isn’t a super-perfect specimen. The rest of the crew sees him as joke, an alcoholic joke. Perhaps the 378 days in space took a toll. Or perhaps he’s such a good cook that the service was willing to overlook his shortcomings. Cook spends a fair bit of time wandering alone on an alien world, making buddies with the natives (well, Robby), and *not* getting torn limb from limb by the guardian. Maybe that was the skill that got Cook his spot: he’s good at surviving alien monsters. Perhaps they see him as a joke too.

[5]But then the Motion Pictures Production Code gave a pass to a 1954 movie like “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers,” a hilarious musical comedy about horny bachelors kidnapping women: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seven_Brides_for_Seven_Brothers

Forbidden Planet was definitely one of Roddenberry’s influences in creating Star Trek, even if he didn’t always want to admit it.

“nigh-godlike aliens” brings to mind Clarke’s Law about sufficiently advanced technology.

The fact nobody bothered to follow up on the Bellerophon for 20 years suggests habitable planets aren’t all that rare. At the same time, there are only about fifty star systems closer than Altair and given how slow FTL is, probably the established trade network has far fewer stars. If they stick to everything within six months of Earth, that’s only about half a dozen systems…

Although perhaps the issue is Altair isn’t conveniently close to other systems humans would be likely to have settled, at least if the interstellar database is a decent guide.

I hadn’t seen Forbidden Planet until just a few years ago (well over a decade after I got really into Star Trek). ’50s social attitudes aside, it was a whole lot less clunky and awkward than I anticipated. Fascinating to see how it very clearly helped establish a template for Roddenberry and a lot of other modern SF tropes.

I still need to improve my underdeveloped knowledge of classic science fiction movies, but this was a good place to start.

It’s a little-known fact that Forbidden Planet had a very loose “sequel” from the same studio, producer, and writer — The Invisible Boy, made the following year as a starring vehicle for Robby. It’s set on Earth in an unspecified near future, but Robby is found disassembled in the laboratory of the late Professor Greenhill, who claimed to have built a time machine and who has a photo of Robby disembarking from a starship at Chicago Spaceport in 2309 — which is consistent with the evidence that Forbidden Planet took place in the 23rd century, though the novelization of that film puts it in 2371. So implicitly, that starship was the C57-D bringing Robby back to Earth (which would put FP in 2299, since it’s a 10-year trip), and the time-traveling Professor Greenhill found Robby there and brought him back. But the title boy has a line about how a time traveler bringing knowledge back from the future would change the present, so I suppose that implies that TIB is an alternate timeline that branched off of the Forbidden Planet universe — or eradicated it, perhaps, but there are enough reasons to dislike the movie as it is.

It’s a bizarrely inconsistent movie tonally. The first half is a rather dull comedy about a whiny brat of a kid with a cold, distant, authoritarian father and the antics he gets into with the superscience Robby provides. Then the title character disappears (from the narrative, not just from view) for most of the rest of the film, and it becomes a solemn thriller about a sentient computer taking over minds and pursuing a Colossus: The Forbin Project-style plan of world domination, with Robby as his reprogrammed slave. It’s quite the bait-and-switch.

Sadly, this was Robby the Robot’s last starring role. The rest of his career would be TV guest appearances and movie cameos, generally as other characters. Way to go, The Invisible Boy, you ruined his feature career.

“lacking Pike’s self-doubt and Kirk’s womanizing ways, he’s too much of a straight arrow to get easily distracted from his orders”

Really, if you look at first-season Kirk, he’s anything but a “womanizer,” but is just as coolly disciplined and devoted to his duty as Adams or Pike. In “Mudd’s Women,” he’s the only human crewmember unaffected by the title characters’ allure, despite Eve’s best efforts to seduce him. He’s only able to express attraction to Rand, Noel, or another female crewmember when in an altered mental state, and the “romance” plots he does have are either reunions with old flames or cases where he’s pretending romantic interest in pursuit of a mission. He did loosen up some over time, due to a mix of the writers being influenced by Shatner’s personality and the pressure to conform to the conventions of ’60s TV in which all male leads were expected to be womanizers. But Kirk was never as much of a womanizer as contemporaries like Jim West or Napoleon Solo, and his modern reputation is really undeserved.

“(which may surprise viewers who are more familiar with Nielsen from his comedic acting days).”

The irony is that Airplane! cast actors like Neilsen, Lloyd Bridges, Peter Graves, and William Shatner (in the sequel) specifically because of their longstanding reputations as ultra-serious dramatic actors, in keeping with the film’s deadpan-farce style, and yet it gave them all new reputations as goofy comedy actors, which they embraced in their post-Airplane! careers.

“Which raises the question of the matter of Earl Holliman’s character, Cook. Cook clearly isn’t a super-perfect specimen.”

Yes, but he’s the token enlisted man. Adams was speaking of the officers who constituted the upper echelon of the crew. I trust it’s clear that “Cook” is not his surname but his job title. He’s the food service guy, the working-class grunt whose job was to keep all those super-perfect specimens fed and entertained. “Everyman” spacers like Cookie were a stock type in ’50s sci-fi films, the relatable civilian among a crew of elite geniuses, the guy who needs all the highfalutin science explained to him as the audience proxy and who provides the comic relief.

I love the movie, but I do want to point out that everything we know about the Great Machine and the Krell come only from Morbius, and he’s a very unreliable narrator. It also harkens to the old belief that high intelligence = high knowledge. Morbius, despite his boasts, wasn’t any smarter than anyone else in the movie.

So, I don’t think that the “plastic educator” actually boosted Morbius’s intelligence. Look at everything it’s attached to, it’s all about using the great machine and not being smart. So what the machine did was not make him smarter, but made him better able to use the machine. And the machine got better at fixing people: The Captain of the Bellerophon died when tried to use the plastic educator, Morbius fell into a coma after he used it, but Doc Ostrow was conscious and somewhat lucid after his go at the machine. Before he died of course. (Big question, if Doc was fixed better than Morbius, why didn’t he try to fix himself using the Great Machine?)

And the fellow that did the novelization of the movie, by Phillip MacDonald, Doc dissects the animals only to find that they were never alive, but were “meat” puppets, created by Morbius’s mind.

Still, these issues aside, I do love this movie and own it outright. I may go watch it again.

Something I didn’t appreciate when I first saw the movie: there are fewer than 20 men on board the C-57D. Adams loses what, a quarter of them? The engineer, the doctor, the lothario, and two more crew at the fence? Plus the habitable planet he was investigating gets blown up. Probably not gonna be a promotion waiting for him when they get home. In his defense, he was hemmed in by standing orders, and the limitations of communications technology (the fact ships could either have ftl drives or ansibles but not both at the same time).

Maybe Doc let himself die because he knew he had his own creatures from the ID and feared the consequences to his fellow spacers if he lived.

Cook is Stephano from “The Tempest”, FP’s source.

Amusing note: I was watching the first episode of Time Tunnel on YouTube last week, and the visuals of “Project Tick Tock” are of the Krell underground factory.

@9/jmeltzer: “I was watching the first episode of Time Tunnel on YouTube last week, and the visuals of “Project Tick Tock” are of the Krell underground factory.”

No, they aren’t the same images, though they were surely an homage. Here are the visuals of Project Tick Tock:

https://twitter.com/beebsf/status/562008509248966656

And the Forbidden Planet matte shots can be seen here (scroll down):

http://nzpetesmatteshot.blogspot.com/2011/03/forbidden-planet-shakespeare-in-space.html

Yeah, FORBIDDEN PLANET is definitely a classic, and it’s probably the most visually impressive pre-2001 SF flick.Some random comments:

Kubrick/Clarke: Arthur C Clarke recommended it to Kubrick as an example of a good SF film while they were prepping 2001. Kubrick hated it…….

Shakespeare…..IN SPACE!: As many people have noted, the parallels to THE TEMPEST are quite strong: Prospero (Morbius) , Miranda (Altaira), Ariel (Robby the Robot), Caliban (Morbius’ monster from the ID), etc

Engineers are miracle workers: The bit where Quinn tells the Adams that he might be able to repair the

“Klystron frequency modulator” has always struck me as being a kind of proto-Scotty “miracle-worker” moment:

Quinn: With every facility of the ship,

I think I might be able to rebuild it…

but frankly, the book says no.

It came packed in liquid boron

in a suspended grav…

Adams:

All right, so it’s impossible.

How long will it take?

Quinn:

Well, if I don’t

stop for breakfast…

Tonight, the Krell orchestra will perform….: Maybe my favorite part of the film is the genuinely alien sounding music that the team of Bebe and Louis Barron devised. Great stuff.

As I recall the sound track wasn’t called music, because calling it music would require certain legal requirements to be met that the company wanted to side step….

@@@@@ 12:”As I recall the sound track wasn’t called music, because calling it music would require certain legal requirements to be met that the company wanted to side step….”

Bebe and Louis Barron weren’t members of the Musicians Union, which meant that their work couldn’t officially qualify as a soundtrack….Which is a damn shame. It’s so alien and creepy, like something that Lovecraft’s Old Ones would listen to a billion years ago….

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oNKhju6Pryg

I admit, the lack of a traditional musical score has always been my least favorite thing about the film. I respect the experimental nature of the soundtrack, but I don’t enjoy it. I like my ’50s movies to have rich, lush orchestral scores. Or jazz, when it’s appropriate.

I was 9 or ten years old when I saw this and it made quite an impression on me. It combined with the works of Heinlien, Norton and Asimov cemented my love of science fiction that persists to this day.

I thank the pioneers who paved the way for the many varied movies and tv shows I have enjoyed over the years

Thank you jmeltzer for reminding us that this is an interpretation of Shakespeare’s Tempest.

I can’t tell you how many times residents have been attempting to explain why something went wrong and I would tell them “it was MONSTERS FROM THE ID!”

Then when they looked blankly at me I would reference the movie and tell them to get off my lawn…

And yes, Seven Brides has some issues with it but Howard Keel and Janet Gaynor.

I watched it as a kid, on I think TNT, when Turner bought up a bunch of classic film libraries to fill out his basic cable channel schedule. They leaned heavily on the Star Trek associations to promote it – LeVar Burton did the ads, and short a short frame as a sort of precursor to TCM’s approach to flicks. My dad was an actor and a little bit of a science fiction nerd (bigger fantasy and horror nerd) so watching it was a requirement – as was making sure I knew of the Tempest connections.

Later, Forbidden Planet would become reconnected with the stage with Return to the Forbidden Planet which would turn the movie into a camp jukebox musical, which I always thought underrated the original film, which deserved a little better. The show itself is quite fun, if odd – it dodges copyright concerns by adapting not Forbidden Planet directly, but the Tempest itself in a way that seems exactly like the film, but with new names, effectively creating a version of the flick with the serial numbers filed off.

I long thought that the flick would do with a remake – it is itself a remake, after a fashion anyway, and the underlying themes of man’s id writ large through technology seems to play pretty well – but then I saw Sphere and thought, no, maybe leave an aged classic alone.

At least FP has a decent reason why the ship doesn’t immediately leg it as soon as it becomes apparent the crew is out of its depth: they can’t because of they need to dismantle the drive to call home. Whereas on Trek some reason has to be provided each week to explain why the away team doesn’t just transport out as soon as the first Greek god shows up.

A tv adaptation that kept the 15C ftl drive could be pretty funny. First episode of the season takes place on a planet, last episode does too, and in between 20 episodes about how 19 bored crew while away the time in space.

@18/James Davis Nicoll: Or, better yet, spend each entire season on a single planet. After all, a planet isn’t one place. It’s thousands and thousands of places. We’ve been exploring this planet we’re on for thousands of years and still haven’t learned everything about it. So it’s really rather preposterous to portray an exploration vessel spending only a few days exploring a planet before moving on. You could easily get a whole season’s worth of adventures out of exploring multiple nations and cultures and biospheres and such on a single world — plus you’d have the budgetary advantage of being able to revisit key locations and reuse standing sets, costumes, and props instead of having to build new ones each week. (In the original 1964 series proposal for Star Trek, Roddenberry actually suggested that one way to keep the show affordable would be to do the occasional 3- or 4-episode story arc so the sets could be reused. Odd that they never tried it.) Then they leave the planet at the end of the season and arrive at a new planet at the start of the next.

On the other hand, aside from things like soap operas, TV shows in the past didn’t follow the current fashion of pretending to take place in real time. If they needed to assert that weeks or months had elapsed between episodes, they’d just do so, jumping over the intervening time. Or if a character had been seriously injured and would need to spend six weeks in the hospital after the episode, he’d be perfectly well again a week later, with the intervening time just skipped right over. Essentially TV shows were written like anthologies — even if the characters were the same, each story was completely independent of the others and little attention was given to how or whether they fit together.

Another person this movie influenced was Jack Chalker. He took the Krell and turned them into the basis for his Well of Souls stories.

Even people who knew Leslie Nielsen from before Airplane! might be a bit surprised to see him here. His time as a leading man was relatively short, and by the mid to late 60s he largely played second tier heavies. Sometimes a professional who was particularly nasty (like his role in Creepshow) but certainly almost never a good guy, let alone a leading man.

@20/DemetriosX: That’s how it felt to me to see Warren Stevens as Doc Ostrow, the most humanistic and decent guy in the film, after growing up seeing him as Rojan in Star Trek and occasional other “heavy” roles. Although of course I was used to Richard Anderson as a good guy from the bionic shows.

Personally I simply adore Altaira’s frank and healthy appreciation of the men, ‘You’re lovely, Doctor, but the two at the end are amazing!’ Here is a heterosexual girl suddenly gifted with a whole ship load of hunky spacemen! Whee! Of course she fixates on the one who doesn’t seem taken with her.

FP is one of the best sci-fi movies ever made. I wish someone would remake and modernize it.

@23/ And, not ruin it a la a the 2008 remake of The Day the Earth Stood Still (ugh!).

As I noted upthread, FORBIDDEN PLANET is probably the most visually spectacular pre-2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY SF film.But is it the best pre-2001 SF film? What would be its main rivals? Off the top of my head, the distinguished competition would be:

METROPOLIS

BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN

ISLAND OF LOST SOULS

THINGS TO COME

THE THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD

THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL

INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS

THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN

lA jETEE

SECONDS

Any Thoughts? Is there a pre-2001 film out there that I’m under-ranking?Is FORBIDDEN PLANET the best of the bunch?

ChristopherLBennett writes in #19:

So it’s really rather preposterous to portray an exploration vessel spending only a few days exploring a planet before moving on.

Right you are. The proper way to explore a planet, as everyone knows, is to send one or two rovers there every decade.

@26/ I agree with many of your selections. I would add: The Time Machine; The Shape of Things to Come; Kiss Me Deadly; Fail-Safe; 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea; and War of the Worlds. There are many other pre-2001 movies.

@26:” I agree with many of your selections. I would add: The Time Machine; The Shape of Things to Come; Kiss Me Deadly; Fail-Safe; 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea; and War of the Worlds. There are many other pre-2001 movies.”

THE TIME MACHINE, WAR OF THE WORLDS, and 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA definitely deserve inclusion. THE SHAPE OF THINGS TO COME made my list (as THINGS TO COME). I don’t think that FAIL-SAFE qualifies as SF (Are there any SF elements? I can’t recall any). KISS ME DEADLY is a tough call…..

@28/trajan23: “I don’t think that FAIL-SAFE qualifies as SF (Are there any SF elements? I can’t recall any).”

It is a speculative work about the possible future consequences of a contemporary technological and cultural trend (the nuclear arms race). That qualifies as science fiction. What makes something SF is the posing of “What if?” questions, extrapolations of current trends into possible futures. There are many works of dystopian SF that don’t involve any science or technology beyond what was known at the time, merely conjectural outcomes to existing trends like nuclear brinksmanship or overpopulation.

@29:

Yeah, but the extrapolative element in FAIL-SAFE is so slight…..It makes DR STRANGELOVE almost look like DUNE in comparison……Of course, Heinlein counted ARROWSMITH as SF…..If that makes the grade, then I suppose that FAIL-SAFE also has to come in….

The Monster from the Id was also a clear influence on the Invisible Monster of Jonny Quest’s first season. The Invisible Monster left footprints in a similar way, but was made visible not by an energy barrier but by the more mundane tactic of dropping paint on it from above.

@29: ISTM that *Fail Safe* is about the consequences of the here-and-now (of when it was written/made), not of a trend; it’s no more SF than (e.g.) Vanished or Seven Days in May.

I liked Return to the Forbidden Planet for what it was: a look back that didn’t take the original entirely seriously. Rather like the musical of Little Shop of Horrors, but starting with better material.

@30/trajan: There’s no sharp dividing line between genres, and no value in erecting or defending imaginary barriers based on arbitrary standards. The intent of Fail-Safe was the same as the intent of any other cautionary tale or near-future dystopia. It’s a “What if?” story and an “If this goes on…” story, which are two of the three foundations of sociological science fiction storytelling as defined by Isaac Asimov (the third being “If only…”).

@32/CHip: Again, you’re drawing an imaginary and useless dividing line within what’s actually a continuum. I definitely consider Seven Days in May an SF story, because it’s a “What if?” story and because it was set a decade in the future of its release. It’s just that its science is political and sociological.

The purpose of genre labels is not to exclude or judge. They’re just rough generalizations for things that, in practice, blend together and overlap in a way that’s impossible to separate cleanly. Where exactly is the dividing line between, say, the troposphere and the stratosphere? Can you pinpoint it to the centimeter? Of course not. The two regions blend continuously into one another, constantly intermixing. Any attempt to define a boundary between them is only approximate and becomes meaningless on the small scale. The point of having the labels is to talk about the general patterns and trends, not to invent nonexistent borders and play keep-out games. There are no borders between genres of fiction, just wide stretches of overlap.

Forbidden Planet is my second favorite sci-fi movie of all time, just barely nudged aside by the original The Day The Earth Stood Still. I first saw it when I was five or six (my Dad had me geeked from birth) on a bootleg vhs. That show blew my mind. It gave me my love for ancient civilizations which eventually turned to those from our own past. This is one of those movies that I both hope and dread that they remake. I’d love to see someone like Anthony Hopkins play Morbius and the cool cgi, but if Hollywood remakes of classics has taught me anything it’s that they don’t understand the classics at all.

As for classic sci-fi to add to the list above how about This Island Earth.

The sticking point for me with some of the other classic SF films is that while Forbidden Planet is based loosely on Shakespeare, if one has read The Tempest it doesn’t really affect the enjoyment of the film.

On the other hand, having read Who Goes There? before seeing The Thing from Another World and having read Farewell to the Master before seeing The Day The Earth Stood Still I can’t get away from the drastic fundamental changes they made.

Who Goes There was a psychological thriller; anyone could be the monster. Farewell to the Master had a twist ending that was potentially more cinematic than making a film that was a Cold War metaphor.

Good films but I can’t escape the baggage they carry…

@34/TimW: Remakes are like any other category of fiction: There are a few brilliant ones and many mediocre or failed ones. It’s never the category’s fault, it’s just Sturgeon’s Law. You just have to hope you get one of the few that fall into the brilliant category (e.g. the modern Planet of the Apes trilogy, or the Bogart Maltese Falcon, which was the third and by far the best adaptation of that story).

As far as remaking Forbidden Planet goes, I admit that Walter Pidgeon’s performance is one of the few things about the film that would be quite easy to improve on. I’ve never quite gotten his appeal as an actor; he’s a pretty stiff, one-note performer in the few things I’ve seen him in. Beyond that, I’m not sure. The film is very much a product of its time in its gender attitudes, to be sure, but sometimes a story needs to be a product of its time. Take away the dynamic of the crewmen and Alta experiencing the temptation of the opposite sex for the first time in months (or ever) and I’m not sure what you replace it with. It would be a very different story.

As for This Island Earth, it’s impressive from a production standpoint, a classic in its way, but it’s really got a pretty lame story. The hero and heroine don’t actually do anything. They get recruited for a weird think tank, they start to investigate, then it gets destroyed and they’re whooshed away to an alien planet and shown around for a few minutes and then flown back and dropped off, and that’s about it. Exeter is the closest thing to an actual protagonist in the film, and his efforts are completely unsuccessful. The film is more flash than substance, as impressive as the flash is for its time.

@35/Dr. Thanatos: It’s not the job of an adaptation to exactly duplicate the original. The original is just the starting point. Some of the best adaptations are completely different from their sources, e.g. Who Framed Roger Rabbit? or How to Train Your Dragon. When watching an adaptation, it’s best just to let it be its own thing, to judge it just on how good a story it is in its own right, not merely its similarity to its source. Picasso’s paintings didn’t look much like their subjects, but that didn’t mean he did them wrong. It just meant his goal was to innovate rather than merely duplicate.

@36 This is why I am glad they changed the names; it makes it easier. Like the Hobbit movies: a different story that happens to have people and locations with the exact same names.

Making an adaptation that is very close to the original is good. Making an adaptation that is markedly different from the original is good. Making an adaptation that is moderately close is problematic as you wind up expecting things that aren’t going to happen…

And for the record it’s not Gort. It’s GNUT.

If Forbidden Planet is remade now, I wonder how the creators would handle the Freudian-Jungian psychology the original movie revolves around?

The FTL here might be slow enough that you can’t do show of the week (a year between adventures adds up pretty quick) but that just makes it ridiculous for Star Trek to be able to fit in so may discoveries. If the new and exotic planets were so close to known and mapped Federation space that you could reach them in a matter of days or even weeks, they would have all been mapped out already. The unexplored space should be places where it is hard or takes a long time to get to.

I expect what’s going on in Trek is that most civilizations explore just long enough to establish that space is full of demigods and all consuming entities, after which they do their best to keep their heads down and avoid attracting attention. Humans on the other hand have the motto “Hold my beer and watch this.”

Babylon 5‘s first season two-parter, ‘A Voice in the Wilderness’, is a homage – in its set design – to Forbidden Planet.

Query: Was this film the first SF to call a planet – Altair IV – by its star and it’s position in its solar system? Something Star Trek picked up on with glee.

@38/Dr. Thanatos: It doesn’t matter if the names are changed or not. Or rather, it’s often better if the names aren’t changed, even when a lot of other stuff is. Variations on a theme are a fundamental part of creativity. Adam West’s Batman and Christian Bale’s are profoundly different in most respects, but they are both still Batman in terms of sharing certain fundamentals. Jeremy Brett’s Sherlock Holmes and Jonny Lee Miller’s are extremely different interpretations of the character and his milieu, but they’re both true to the character in the ways that matter. Part of the joy of creativity is encountering something familiar and getting to see it in a totally new way. It’s that blend of recognition and novelty that keeps it interesting. It loses something important if you sever all connections to the thing it reinvents.

“Making an adaptation that is moderately close is problematic as you wind up expecting things that aren’t going to happen…”

There is nothing the slightest bit problematic about giving an audience something it doesn’t expect. That is desirable. A story that has no surprises is boring and pointless. If the story doesn’t give you anything that doesn’t already exist inside your head, then it’s a complete waste of time.

@40/vinsentient: “If the new and exotic planets were so close to known and mapped Federation space that you could reach them in a matter of days or even weeks, they would have all been mapped out already.”

Not really, because it’s not just a matter of distance, it’s a matter of quantity. This site gives an estimate of nearly 15,000 stars within 100 light years of Earth. Current models suggest that nearly every star system has a planetary system. Let’s say you manage to explore one new star system per week — that’s still only 52 systems per year, and it would take 288 years at that pace to visit every star system within 100 ly even one time each.

@42/a-j: “Query: Was this film the first SF to call a planet – Altair IV – by its star and it’s position in its solar system? Something Star Trek picked up on with glee.”

Oh, it’s much older than FP. Like many, many things in science fiction, it dates back at least as far as E.E. “Doc” Smith’s pulp stories in the 1930s. And that in turn is adapted from the numbering system that Galileo introduced for the moons of Jupiter, which was standard through the 19th century.

https://scifi.stackexchange.com/questions/218766/sol-%E2%85%A2-earth-what-is-the-origin-of-this-planetary-naming-scheme

I love Forbidden Planet but I’m not partial to the Theremin score. The thing that does it for me is the Krell and the machine they built. Attempting to show the scale of the machinery and the power generated within the planet’s reactors create something that not many SciFi shows have done. The power of 10 taken almost to infinity. It is one of those where the concept becomes almost incomprehensible.

The Dyson Sphere in Star Trek Next Gen is one I can think of without researching the subject. Maybe the Death Star….

Feel free to add your suggestions!

There have been discussions about remaking Forbidden Planet, but I am against ruining a classic. How may SciFi sequels have been better than the original?

@44/Zeus: FP’s score didn’t use a theremin, but a distinct electronic instrument created by composer Louis Barron. A major component of it was a ring modulator, the same kind of device later used to process Dalek voices in Doctor Who.

“There have been discussions about remaking Forbidden Planet, but I am against ruining a classic.”

A bad remake doesn’t ruin the original, because the original is still there. Generally if a remake is bad, it will just be forgotten while the original is still remembered. I rarely hear much discussion of the Keanu Reeves remake of The Day the Earth Stood Still, for instance. When people bring up that title, they’re still usually talking about the Michael Rennie version. So if anything, a bad remake only ruins itself.

“How may SciFi sequels have been better than the original?”

Are we talking about remakes or sequels? There have been a number of sequels that improved on their predecessors — The Empire Strikes Back, Terminator 2, The Dark Knight, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, etc. As for remakes, there are those who consider John Carpenter’s The Thing and Philip Kaufman’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers superior to the 1950s originals, or at least equally good in a different way. I’d say the 1931 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is far superior to the earlier silent version, though the 1941 remake is markedly inferior. And the modern Planet of the Apes trilogy is at least as good as the original PotA and markedly better than the sequels it’s loosely based on (Conquest of…, and Battle for…).

@43/Christopher L Bennett

Thanks for the info and link.

@ChristopherLBennett: the problem with claiming anything in the gray area as SF is that one winds up saying that imagination is forbidden in not-SF, rather like the position taken by some older readers that there’s nothing worthwhile in contemporary mundane fiction (this often in reaction to the opinion (that they grew up fighting against) that all SF is trash). At the very least, we need a term acknowledging that a work is in a gray area, rather than making a Campbellesque claim.

Time was when the standard rule for SF (or at least for “science fiction”, back when fantasy was largely either artsy or mundane) was that the author was allowed one current impossibility (including things categorized as we-can’t-rule-this-out-but-we-are-nowhere-near-being-able-to-do-it) and was supposed to extrapolate convincingly and non-miraculously from that. (In some ways this was an ideal, in that many tropes became part of an assumed future rather than being individually justified.) Does (e.g.) It Can’t Happen Here depend on anything other than the demonstrated viciousness that can surface in many (all?) people under the wrong circumstances?

I would also argue that neither politics nor sociology is a science; one can write SF about them becoming sciences (e.g. Foundation), but ISTM that’s different from calling any story about what-could-happen-right-now-if-somebody-were-crazy SF. (I wonder whether Seven Days in May was set in the future because Knebel didn’t want to deal with an explosion of fury from knee-jerk worshippers of the military; I read it so long ago that I couldn’t say whether it actually depended on any change even if I had a thorough knowledge of military politics at a time when I was in grade school.)

A Randall Garrett character said that black magic is a matter of symbolism and intent. Both of these are gray areas in themselves, but ISTM that the epigram can also be applied to SF — and to the various divisions within it

@47/CHip: “the problem with claiming anything in the gray area as SF is that one winds up saying that imagination is forbidden in not-SF”

No, because my whole point is that it’s ridiculous to treat this as an absolute either-or question and toss around melodramatic words like “forbidden.” These are not nations with impassable borders. Labels are not more important than the things they describe. They are not ideologies or value judgments. They are just approximate descriptions that should not be taken overly seriously and absolutely should not be used as an excuse for petty territorial wars.

In any case, obviously all fiction is imagination, but what’s at issue here is the specific type of thing being imagined. If it’s a story set in the near future that shows a conjectural outcome to the continuation of existing trends, and if it does so as a cautionary tale, then it is employing the syntax of a science fiction story, even if it doesn’t have the semantics of futuristic technology or aliens or whatever. Too many people define genre based solely on semantics, the surface forms and trappings, rather than the syntax, the form and structure of the story being told. For instance, Star Wars has the semantics of space opera but the syntax of a sword-and-sorcery fantasy. Outland has the semantics of science fiction but the syntax of a Western. And so on.

The purpose of these categories is not to exclude or judge, merely to evaluate and understand. It’s ridiculous to think that a story that has one quality is somehow “forbidden” to have others at the same time. These are all just ingredients, and any story can use them in any number of different mixes. It’s the infinite variety of possible combinations that makes creativity so interesting, and erecting imaginary walls and Keep Out signs just narrows your range of options for no reason.

“I would also argue that neither politics nor sociology is a science”

I think that’s a prejudice, and just one more excuse for petty gatekeeping games that only get in the way of true understanding.

Perhaps, there are two main types of science which are at opposite ends of a continuum: 1. Science with a big S; and 2. science with a little s. Science with a big S is exemplified by physics, chemistry, mathematics and biology (high predictability of outcomes). Whereas, science with a small s is exemplified by history, law, sociology and Freudian psychology (low predictability of outcomes).

@49/Continued: Therefore, the subject matter of sci-fi can fall anywhere between the poles of big S science and little s science.

@49/Paladin Burke: Anyway, it really doesn’t matter, because the “S” in “SF” can stand for “speculative” as well as “science.” A lot of SF is about conjectural societal or historical trends rather than scientific progress — for instance, the alternate history genre. The point is to explore hypotheticals, to ask what-if questions and explore possible answers.

If anything, that’s where the real science comes in, because science is a process of investigating possibilities. Science is posing a hypothesis and putting it to a test. A work of speculative fiction is a form of thought experiment, putting forth a hypothetical situation and extrapolating its possible outcome based on knowledge and reasoning. Knowing what we know about the world, if such-and-such a thing happened, what would be a plausible result of it?

@51/CLB Agreed.

One of the reasons this movie stands out is it was the first SciFi movie that “played it straight.” All previous scifi movies were over the top and a bit comical. This one was done with the help of Disney for its special effects and there were no obvious, goofy looking, rubber costumed aliens running around. Yes, it looked dated compared to modern scifi, but this was the movie that turned the corner for all future scifi movies.

Ahem. James T. Kirk was not a womanizer. He was a charismatic and caring person whom women (and many others) found very appealing. For example, Kirk was much more kind and compassionate than polyamorous “womanizer” Captain Jack Harkness from Doctor Who/Torchwood.

@53/Scott Chandler: “One of the reasons this movie stands out is it was the first SciFi movie that “played it straight.” All previous scifi movies were over the top and a bit comical.”

That’s not even remotely true. There were plenty of previous SF movies that played it straight. Just a partial list would include Metropolis, Frau im Mond, Things to Come, the early Universal Monsters films like Frankenstein and The Invisible Man, Destination Moon, Rocketship X-M, The Day the Earth Stood Still, The Thing from Another World, When Worlds Collide, It Came from Outer Space, The War of the Worlds, the original Godzilla, Conquest of Space, The Quatermass Xperiment, This Island Earth, and Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

If memory serves, what made Forbidden Planet stand out from other genre movies of the day was that it was produced as an “A” movie instead of a “B” movie, with an unusually high budget and commensurate production values. Although it wasn’t unique in that regard, since there were some previous movies known for their elaborate FX such as The War of the Worlds and This Island Earth.

@54/Caryn: Quite right. Kirk was more often the pursued than the pursuer.

“3: The C-57D has awful ergonomics. Partly because it’s disc-shaped, which means there are hard to exploit volumes.”

And with that statement, the author just shot down the whole idea that alien flying saucers are visiting Earth: Saucer shaped craft are just a crappy design.

Well, it may be other factors trump ease of use. I mean, giant flying boxes would be easier to fit rows of seats into than are airplanes but the need for an aerodynamic shape says we’re stuck with rounded tubes. Maybe there’s something about how the FTL or space drive works that forces that shape on the designers.

Could be worse! The safest interstellar wormholes available for travellers in The Space Eater were only about the width of a human thumb, which was very hard on the people passing through them.

#25 Dude! “Frau Im Mond” – first use of countdowns, first use of acceleration couches. Also from Fritz Lang, the first three Dr. Mabuse movies, and Spione, which really created the template for the super-spy technothriller genre.

Also, “King Kong”, and the ’30s version of “She”.

I just rewatched this a couple of months ago. I still enjoy it.

As a kid, the ID monster scared the hell out of me. Then one day I was watching it again and realized that the monster is the Tasmanian Devil from the Bugs Bunny cartoons.

One of the reasons a lot of the special effects hold up so well is that a lot of the work is hand-drawn animation by Disney’s Joshua Meador, whose credits for the Mouse included work on 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and Fantasia. That stuff is golden–literally timeless, looking as good now as it did in 1956. MGM and Disney worked out some kind of trade (I no longer recall the details) that let Meador come over to MGM to work on Forbidden Planet. The Monster From the Id is definitely his work; I have not been able to figure out if he played any role in the C-57D’s flight sequences or the matte work in the Krell city (which is also pretty glorious in its own right).

My daughter and I just saw Forbidden Planet for the first time and boy, is it a stinker.

“Egregious 1950s sexism aside”

No.

There were science fiction films being made at that time that did not buy into the gross chauvinism promulgated in that movie (e.g. “I married a monster from outer space” is a good example). That egregious sexism was not uncommon doesn’t make it overlookable.

Plus, Commander Adams has got to be the worst skipper ever.

“Don’t land on the planet, Commander! If you do…” [shuts off communications]

“Something invisible came on the ship and sabotaged valuable equipment? It’s all your fault, sailor for not seeing it! You’re on report!”

(but didn’t the shipwrecked scientist JUST WARN THE CAPTAIN ABOUT A PRESENCE ON THE PLANET KILLING THE CREW OF THE BELLEROPHON? AT LENGTH?!?)

When the film wasn’t disgusting us with sexual assault or unbelievably lax military discipline or plain character stupidity, it was boring us. I was trying to understand Walter Pidgeon’s strangely flat line delivery during his monologues. After the first few, it dawned on me that he was simply reading off of cue cards.

And we figured out “whodunnit” about halfway through the movie.

Tremendous special effects, amazing soundtrack, great set design. If only there’d been a worthy movie in the movie.

(and before anyone comes back with, “Well, that’s just your modern perspective,” I encourage you to visit Galactic Journey — our modern perspective is only nine years removed from the film’s release)

@61/Gideon: I don’t think we’re overlooking the sexism, just acknowledging that the same work can have good and bad aspects at the same time, and that it’s too simplistic to throw the whole thing out because it has flaws. The gender values of the film are quaint and implausible, but they’re not the entire film. And just because something wasn’t the most progressive creation of its time doesn’t mean it has zero value.

Saying “X aside” does not equal overlooking X or pretending it doesn’t exist. On the contrary, it’s acknowledging that it’s real and significant, but then moving on to a different part of the analysis. Few things are monovalued.

“You know, problematic anti-Semitic content aside, Triumph of the Will is a cracking good watch!”

The gender values of the film are beyond quaint. They are offensive. “Look at you! Flouncing those legs. Why, I should have let that Lieutenant have his way with you. How can I, a ship’s captain, be expected to keep my crew in line with you running around dressed like that?”

(paraphrased, this is exactly what Adams says in the film).

But beyond that, the plot is just dumb, from the very first utter disregard of the philologist’s warning.

The effects are masterful, the set design breathtaking, and the soundtrack superb. But the offensiveness of the (well-acknowledged sexism) and the inanity of the characters’ decisions (not to mention the utter unlikability of every character in the film — except maybe Robby) made the film a chore to watch.

In the end, I don’t think we’re disagreeing on the content of the film. We just have different tolerances for the agreed-upon badness. Forbidden Planet passed the threshold of salvage for us, even as we concede the elements that were impressive.

@63/Gideon: Wow, you went Godwin really fast there. Obviously there’s a massive difference between a political propaganda film and a work of entertainment perpetuating unexamined stereotypes, so that analogy was completely uncalled for.

A zero-tolerance attitude toward the mistakes of the past is arrogant and blind, because it presumes that we ourselves are infallible. This is self-congratulatory BS. I guarantee you that no matter how progressive and fair and inclusive we try to be, our children and grandchildren will look at our creations and go “How could they have been so ignorant and prejudiced about [X category that hasn’t yet emerged as a civil rights issue]?” Heck, I’ve only been a professional writer for 22 years and I’ve already found unintentional biases and insensitivities in my earlier works that I’ve had to remove in reprints, despite my attempts to be as inclusive and progressive as possible. Learning is a lifelong process, and we surely have as much left to learn today, and as great a capacity for making mistakes and bad choices, as our forebears did generations ago. So let he who is without sin, etc. etc.

@63, Oh please! Altaira is totally enjoying getting male attention and admiration for the first time in her life. And the crew are behaving quite well. Nobody does anything to Altaira that she doesn’t invite and welcome. She is being procative, quite deliberately imo, and the Captain has problems with it because he’s as affected as anybody.

I’ll concede the Riefenstahl was hyperbolic. How about Song of the South as a better example?

And I absolutely agree that the past needs to be viewed in context. That’s the whole point of the work we do at Galactic Journey.

Forbidden Planet’s chauvinism is not egregious because it was made in the 1950s, it was egregious even for the 1950s! There were plenty of SF movies made in that era that didn’t have the problematic issues of Forbidden Planet. So it doesn’t get a free pass for being old any more than Randall Garrett’s Queen Bee does.

@66/Gideon: Yes, it’s egregious for its time. That doesn’t mean every copy should be burned, or that we’re not allowed to recognize the parts of it that are still worthwhile. Life is complicated. Things are allowed to be more than one thing. You can criticize something’s flaws and celebrate its virtues at the same time.

And there’s virtually no creative work from the past that isn’t backward by our standards in one way or another. That’s what backward means. And that’s why forgiveness is a thing. A person can be a jerk and a screwup but still have things you love and accept about them, so you forgive them for their flaws. And the same goes for works of fiction. Even badly flawed entities can have redeeming virtues.

Quick reminder: You’re welcome to disagree with the opinions expressed in the article or in the comments, but please keep the tone of the discussion civil and constructive; aggressive or dismissive comments do not help to further the conversation. Our full commenting guidelines can be found here.