As happens from time to time, I recently noticed an author1 being subjected to complaints that their fiction has an “agenda,” that there are “political elements” in their story, that it touches on society, class, race, culture, gender, and history. As it happens, the calumniated author is one of those younger authors, someone who’s probably never owned a slide-rule or an IBM Selectric. Probably never had ink-well holes in their school desks.2 Undoubtedly, they may be missing context that I, a person of somewhat more advanced years, can provide.

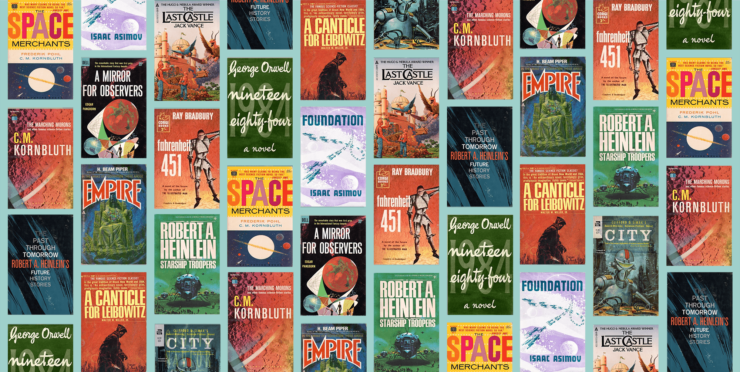

Golden Age science fiction was, of course, a wonder of agenda-free writing: No political, racial, or gender concerns tainted their deadly deathless prose. Heck, a lot of old-timey SF never so much as hinted that visible minorities or women even existed! Modern authors might find these old-style works inspiring. Perhaps some examples are in order.

(Sadly, there is still no sarcasm font available on this site…)

Young Isaac Asimov, for example, was a self-confessed Futurian, which was a left-wing group. Some Futurians were once banned from WorldCon for their political views. But not Asimov; he was too popular to exclude. Nor did he allow his personal politics to taint his fiction. Consider his Foundation series (1951)—which, as we all know, is about a one-thousand-year effort to covertly place all significant political power in the Milky Way in the hands of a small, secretive elite.

Cyril Kornbluth, also a Futurian, similarly kept his SF utterly free of any political statements of the sort I might have noticed when I was a teenager. Instead, he focused on politics-free entertainment like “The Marching Morons” (1951), a value-neutral story about how sometimes the best solution for life’s challenges is to just kill society’s least-fit 90 percent.

John W. Campbell’s Astounding once bestrode the world of SF fandom like the Colossus of Rhodes, thanks in large part to politically neutral stories like Randall Garrett’s “The Queen Bee” (1958), an amusing tale about compelling women to submit to endless baby-making under frontier conditions (whether or not they want children). Astounding also published H. Beam Piper’s “A Slave is a Slave” (1962), an utterly context-independent story—coincidentally published about the time the American Civil Rights movement was underway—which assures the reader that “the downtrodden and long-suffering proletariat aren’t at all good or innocent or virtuous. They are just incompetent (…).” Then there was Heinlein’s “If This Goes On—” (1940), an apolitical tale about freedom-loving rebels confronting an oppressive theocracy. I challenge the pickiest reader to detect any sort of political agenda in these stories!

Galaxy magazine, an Astounding rival, competed for the same audience with its own slate of politics-free stories, like Vance’s The Last Castle (1966), in which effete and ineffective aristocrats struggle to survive the wrath of slaves threatened with a return to their former, quite savage, homeland. It also published Ray Bradbury’s “The Fireman,” in which firemen manfully pursue their duty to rid America of books (this was later expanded into the best-selling novel Fahrenheit 451 [1953]). It published Pohl and Kornbluth’s serial Gravy Planet (later published as The Space Merchants [1952]), in which society enjoys the full benefits of a consumerist society untrammelled by concerns other than the bottom line. Each one of these texts is a gem of transparent storytelling, without the slightest taint of subtext. Or at least they were when teenage me read them…

This careful, purposeful neutrality extended to novel-length works as well: Clifford Simak’s City (1952), for example, details humanity’s long, slow, inexorable decline towards irrelevance and extinction thanks to a long series of well-meaning but unfortunate decisions. I can’t think of any real-world issues this fix-up, composed shortly after the Atomic Bomb made total human extermination a real possibility, could possibly be referencing.

Similarly, Walter M. Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959) is a straightforward whizzbanger about monks bravely preserving knowledge in the face of global thermonuclear war for an age when humanity, having learned nothing from radiation-scoured wastelands and centuries of dark ages, might wish once again to make use of said knowledge to lay waste to the world. Modern writers might have ruined the story with intrusive moralizing. Miller comforts the reader with wholesome adventure fare: musings on the morality of euthanasia and the human proclivity to repeat the failures of the past:

Listen, are we helpless? Are we doomed to do it again and again and again? Have we no choice but to play the Phoenix in an unending sequence of rise and fall?

Let tales like those above, and all the works like them—Starship Troopers (1959), A Mirror for Observers (1955), Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), and so on—stand as examples of the straightforward, uncomplicated, and above all issue-free science fiction authors could craft, if only they tried.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is currently a finalist for the 2020 Best Fan Writer Hugo Award and is surprisingly flammable.

[1]Whom I am not naming out of a desire to avoid sending irate commenters their way, as they appear to have attracted a sufficient supply already.

[2]I am not quite old enough to remember when the ink-well holes in school desks actually had ink-wells in them. Not quite. I am “ubiquitous and cheap ballpoint pens” years old.

When I first saw the title, I thought it was going to be a short article. Instead, I got the bait and switch treatment! :-)

I doubt the people who complain about SF not being apolitical enough will have sufficient grasp of subtlety to recognize the true point of this article.

I’m older than you by the inkwell standard, and almost as well read, and my comment to this excellent article is: **snicker**

YOu can’t be serious. those stories are all biased agendas.

My older brother is not much older than I am but old enough to remember before-cheap-ballpoint-pens. I had no idea there had been a technological shift in writing implements in the late fifties, early sixties until I read a Ray Bradbury from the 1950s that off-handedly referenced ink wells in a story set in the 1970s.

(One of my father’s many on going feuds involved felt-tip pens, which he preferred, and Toronto Dominion Bank, who absolutely refused to honour checks signed in felt-tip because the ink would bleed)

I giggled all the way through this. Very entertaining indeed.

As always, we ask that you keep the tone of the discussion civil and constructive; our moderation guidelines can be found here.

@2: I suspect we’re going to see that very point demonstrated in the comments.

On this site and others, I get pretty dang frustrated by the younglings and their fondness for seeing everything from some political, social, or gender bias, but, sadly, this is trained into them in college in place of looking at the work, first as a work. “New Criticism” which did this was already dying when I was in graduate school in the Seventies. Sometimes, I want to smack the young whippersnappers and tell them, “No, it’s not all about you. It’s about the work, itself.” Then I tell them to get off my lawn.

This is almost making me feel sorry for the comment moderators. Do you get hazard pay when dealing with snarky articles?

Despite the fact I sprinkle sarcasm on my essays like salt on food, I have essentially no ability to recognize sarcasm in the wild, so I really should cut fellow sarcasm-challenged persons some slack.

@11: Ha–we do not…but, you know, most of our commenters are wonderful, so it works out okay :)

Well, *I* certainly recall inkwell holes in the upper right corner of our stationary wooden desks, and ink stains on my fingers!

Being so young when I read all that Golden Age SFF, happily I didn’t notice any issues. I didn’t know what they were.

Nowadays, I still despise ballpoint pens and people who push authors to write about “issues”.

Twitter needs a sarcasm font, too. I’d wear it out.

0: “Some Futurians were once banned from WorldCon for their political views. But not Asimov; he was too popular to exclude.” I’m going to nitpick this. At the time of the Great Exclusion, I suspect that Asimov was too unknown to exclude. He’d published almost nothing at that point, and was not the social butterfly he’d later become.

There’s really nothing like revisiting a childhood favourite to discover Women in Fridges was a thing as far back as the Swinging Sixties, as were comedic rape jokes, and that the endearing tale of post-apocalyptic recovery stocked by many Canadian schools found time for a really vicious Antisemitic caricature.

Does the Star Trek:TOS count as classic SF? “We’re NOT… GOING… to SUBTEXT… AGAIN…. TODAY. We’re NOT going to SUBTEXT AGAIN… TODAY. Maybe next week.”

@17 – Not just Canadian elementary schools, and thanks for being the suck fairy for that memory :-)

I remember inkwell holes in desks, although the inkwells were long gone. We used them to play “desktop golf” with pencils and spitballs.

Middle school me in the 1990’s found Isaac Asimov and loved all his stories. I grabbed all I could from the library. I didn’t pick up on the politics, I just liked the space adventures, mysteries, and engendering puzzles of them.

However one thing I did notice was the lack of women. His stories might not of been aiming to say women can only be secretaries, nurses, wives, or daughters; but that is what I saw. Because all of his female characters were that. (except Susan Calvin). I did not take that as a lesson that I should want to be just a wife, or nurse, but I was upset that he didn’t use more women in his stories.

After I branched out to other books I found a more variety of characters. But a lot of the SF authors from that time had a similar cast of females in their stories: damsel in distress, secretary, nurse, wife etc.

I wonder if I could sell tor a Five Books Whose Authors Meant Well.

@5 Oh, I think he’s definitely not serious. I would interpret his serious point as: political agendas in one form or another have been in fiction for at least the length of the genre, and — I will go further in my hypothesizing — the belief that many older folk have that they didn’t do political agendas back in The Olden Times is because as readers these older folk were not equipped to recognize political agendas.

There is a political agenda in Gernsback’s scientifiction. There is a political agenda in Shelley’s Frankenstein.

I have not asked James whether that is his point; I make no claims for mind reading. But that’s what I might draw from the examples.

And I’ll admit that in my yout’ I read many stories without a political agenda that I could recognize, but they shaped my beliefs anyway. Some of those beliefs I had to forcibly reject, some I have come to embrace overtly. Some, I am sure, I have not recognized yet. (I’m not yet 60; there’s still time to change. Even though I am annoyed at my children challenging my beliefs and teachings, I recognize that it’s generally a good thing. It staves off hardening of the thoughteries.)

I’m a bit curious which SF author(s) are the targets of ire that inspired this piece, but all I could think of while reading it was how often I’ve seen the same shit when it comes to comics and films based on them. “Why is Captain America so political?” “Why are the X-Men such SJWs?”

Well, dingbat, Captain America got his start literally punching Nazis, the X-Men have always been an allegory for racism, sexism, and all of the other bigotries people like to wallow in, and every damn superhero is a literal social justice warrior.

Your examples cover the entire political landscape, as it should be. My problem with current SF is the politics is almost entirely one-sided, and there are significant efforts to deplatform or shout down authors with other viewpoints, and to shame their fans (even when said fans are also ones’ customers).

Except the version of the Greg Saunders Vigilante who showed up in Jones and Parobeck’s El Diablo #12, who was astounded to discover El Diablo was a liberal Democrat.

@17: Can you provide the footnote about the post-apocalyptic novel?

“Does the Star Trek:TOS count as classic SF? “We’re NOT… GOING… to SUBTEXT… AGAIN…. TODAY. We’re NOT going to SUBTEXT AGAIN… TODAY. Maybe next week.””

I lit off recently on an idiot who was joining in the constant moaning that Picard and Discovery were so unlike Star Trek because they were trying to be woke, SJW, whatever, and why couldn’t it be like TOS which wasn’t laden down with political messages?

I pointed out that for someone claiming to be a long-time fan, he clearly didn’t know crap about Star Trek. Many episodes didn’t have subtext; calling it outright text would have been understating what a complete sledgehammer-to-the-forehead-anvil-dropping they could get into: “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield”, anyone? The only reason he didn’t recognize it being as politically provoking for its time as anything he’d whine about now is that he first saw it too young to get the context, and by the time he saw it old enough to understand the context the message wasn’t controversial anymore.

I fear that Mr Nicoll will never speak clearly again, after sticking his tongue this far into his cheek…

@22 I would say yes, and I for one would enjoy seeing it!

On a sarcasm font. I’ve noticed that some people use /s at the end of a comment to show it was sarcasm. It took me a long time to figure this out. I prefer sarcasm –> <– sarcasm myself because so many of us are clueless about the latest Twitter or Reddit usage. And don’t get me started on emojis. I can barely figure out the differences on those teeny-tiny little faces with my older eyes, let alone figure out what they mean.

@28 You comment about Star Trek always having a message reminded me of Steve Shives on YouTube. He does some great video essays on Star Trek. Two are relevant here.

SJWs Invented Star Trek: https://youtu.be/LX1oYSNPV5k

What Do Conservatives Actually Like About Star Trek?: https://youtu.be/nNNWWdsEYGg

@28, How young do you have to be to miss the reverberating anvil drop in Let That Be Your Last Battlefield? I winced at it when I was thirteen in the 70s.

Oh dear.

He had to go whack the hornets’ nest. A virtual beverage for the mods and their labors.

Still, yeah.

Even in my more callow days of the 80’s and 90’s I could recognize that a lot of the stories had agendas, even some of my favorites. I didn’t care at the time mind you, or agreed (thankfully we tend to grow up as we grow older), but as I’ve gotten older, well, I wince at some of the stuff I read and enjoyed when I was younger and didn’t know any better.

I suspect that Star Trek’s anvils are sometimes glossed over because, to a certain mindset, a white man in authority delivering a message authoritatively is, almost regardless of the content, less ‘political’ than, to take Discovery for instance, a show featuring a woman of color as its main character.

@17 – Yes, that post-apocalyptic novel with the vicious antisemitic trope. The suck fairy didn’t come for it — I remember reading it in my teens, decades ago, just agog with horror. This was a ‘classic’? I already felt invisible and erased in what I read (aside from the occasional Harlan Ellison very short story about making up a minyan on a planet with 8 other people on it, a Peter Beagle novel or two, and the collected works of Avram Davidson ;). After reading that post-bomb novel, I felt physically unclean. Still do when I think of it. Ugh.

This is the first time I’ve seen someone refer to that. Thank you JDN – I had long wondered about the silence, and questioned my reading comprehension. Its reassuring to know other people were also thrown, if not triggered.

I love this article with a fierceness. The sarcastic tone had me smiling and chuckling throughout. From now on, whenever I see the criticism that an author should keep their agenda out of their fiction and just give us explosions and ray guns, this will be the article I link them to. Bravo.

27: Suzanne Martel’s Quatre Montréalais en l’an 3000, AKA Surréal 3000, AKA The City Under Ground focuses on recontact between two Montreal groups, one in a Science! City under Mt Royal and the other living lives of bucolic peace on the surface, complicated by the discovery of a third group stealing resources from the first. The first group appeared to be descendants of the French, the second are Anglos, but the third? Well, they are described as short, bearded, hideous, and they speak a third “guttural language”.

Quebec’s third solitude.

Definitely needs a sarcasm/snark font.

Amazing that anyone claims not to know that literature always has an ax to grind; the question appears to be the artistry and inaudibility of the grinding. Readers/Critics who agree with the author in question call this relevance; those who don’t call it an agenda. Let’s remember Rilke:

“Archaic Torso of Apollo” by Rainer Maria Rilke

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,

gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could

a smile run through the placid hips and thighs

to that dark center where procreation flared.

Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

(emphasis added)

@31 – James does not normally truck in anything so crass as pure sarcasm. One might say, rather, that he is a household object useful for the pressing of wrinkled fabric.

@22 I would really really love to read that article. Please don’t just limit yourself to five.

@23 – Thank you for the phrase “hardening of the thoughteries”, pure brilliance.

@25 – the politics is almost entirely one-sided, and there are significant efforts to deplatform or shout down authors with other viewpoints

Neither of those things is true – there are plenty of conservative-minded authors out there. Dan Simmons springs immediately to mind. And whatever “deplatforming” exists isn’t simply due to conservatism, or to the actual writings of those authors. It exists because they make very specifically bigoted and/or hateful public statements. The problem is that virtually all of American conservatism has openly embraced such views.

Ah, I thought you might be referring to Canticle for Leibowitz, which I first read in my Grade 12 English class’s SF module: a post-apocalyptic recovery novel with a notable weird semitic character.

@16: Astounding (p. 107) suggests that the truth of the matter may be lost to history:

Sourced from The Immortal Storm and In Memory Yet Green, which I don’t have copies of at hand.

Just some additional reminders here, to keep things civil and respectful–let’s try to avoid making sweeping blanket statements, which are rarely (if ever) helpful. Same with casual name-calling; it doesn’t lead anywhere constructive in this type of conversation. Thanks, all!

When the question of political sf first came up, it occurred to me that sf set far enough in the future to require world building can’t help but be political because there has to be something about what political and economic arrangements are possible and how they work out.

Does it take any of the curse off “The Marching Morons” that the man who orchestrates the genocide is killed for it? This is an honest question.

I’m not sure how much Garrett’s “The Queen Bee” Counts for. It got published, but I don’t think it was famous. If Garrett is remembered it’s for his Lord Darcy stories.

I remember back when I was in 6th grade, we still had the inkwell holes in our desks. One parent-teacher night, my teacher was speaking to a group of parents, and went to sit on the corner of a desk, not realizing that one of the kids left a sharp pencil sticking out of the inkwell hole point up.

My mother said later that it was the best parent-teacher night she had ever been to.

@39: Thanks

US public school in the 1980s. I’m wondering if our desks had a mysterious hole we didn’t have a name or function for.

I tend to agree with George Orwell that all art has a political dimension, whatever the conscious intention of its creator. Certainly overtly and consciously political science fiction is nothing new. I suspect those who complain about stories being “political” are more often really complaining about a political message they don’t happen to like.

Me, I don’t care much about the politics of authors. I’ve loved fantasy by authors who ranged from communists (Olaf Stapledon) to reactionaries (Michel Houellebecq), from conservative Christians (C.S. Lewis) to radical anarchists (Michael Moorcock), from feminists (Ursula Le Guin) to unabashed masculinists (Robert E. Howard), and from a plethora of points across the whole spectrum between. If you require fiction to line up with your political values in order to appreciate it, or assess its merit based on how well it conforms to those values, I’d say you lack both aesthetic discernment and readerly courage.

All that said, it does seem that the political messages in much recent science fiction are often simplistic and heavy handed, almost invariably to its detriment as art. Although I suppose there’s nothing new about that either.

So. Recently, in this time of lockdown, I tried rereading Asimov’s robot stories. Oh man. Sometime in the past couple of decades they became unreadable

2, 3, 7, 29, and 38: I’m with you all (especially because you said almost everything I wanted to say!) It’s nice to read an essay that leaves you chuckling. As for the inkwells, I spent one year in the 1950’s (yes, I’m old) in elementary school in Alabama — don’t ask — and we USED the inkwells for the ink bottles for our required fountain pens. Oddly, though I hate practically every other memory of that year, I still like using a fountain pen.

Sigh of relief, I thought the post-apocalyptic novel being referenced was `The Chrysalids’, which I admire. It was (and is still?) popular in high schools some decades ago.

There was an in-universe version of this debate in The Mote in God’s Eye. All Motie art is created by Mediators, the communications and diplomacy caste, and all art is intended to communicate something. They take it so far they don’t even paint landscapes without Moties doing something in them. Their reasoning is that you can’t expend all that effort creating art if you have nothing to say. The humans disagree on whether this applies to human art too.

Another classics without any agenda whatsoever: A & B Strugatsky, The Inhabited Island.

Anyone who is pining for something a touch more right-wing than the usual fare here at Tor can head over to Baen Books to get their fix.

@55

I, too, long for the subtle politics of RAH and the Niven/Pournelle milieu of a quarter to half a century ago.

An aspect of The Chrysalids that I overlooked as a kid was how, having spend the book building a case against murdering people over supposed mutations, the novel ends with a touching little homily about the necessity of genocide of the old by the new:

I have a particular (and maybe perverse) soft spot for SF in which the author’s agenda led to them creating something so imaginatively powerful that the original point gets lost in the mix. For example, I loved A Matter of Size by Howard Fast as a teenager, but I never really picked up on what it was about until re-reading it years later.* Sometimes the rationale is lost in the mists of time. A blogger (Occasional Mumblings) was doing a story-by-story review of Nightfall recently and gave the history behind my favourite story in the collection – Hostess. Apparently, John Campbell insisted any stories in Astounding had to depict Man as the superior species. So when Galaxy started up, Asimov composed a story suggesting the exact opposite: ie, in a galaxy shared by five or six other species, man is the odd one out by virtue of his inferiority rather than his superiority.

* Another example is Planet of the Apes. The Burton remake largely ignores the subtext (he was more interested in the concept’s visual appeal).

@10: Or one could try going back to old-school philology, predating the New Criticism, all the while ignoring what the New Criticism was reacting to (and the personal interests of the most-prominent New Critics). But there was no political agenda in that at all. Nope, no inherited-wealth subtext, or different-shades-of-imperialism issues, or linguistic-paradigm-in-service-of-power presumptions, or limitations-on-social-mobility aspirations, or public-schoolboys-against-the-proles issues there at all. All the while lamenting the lack of a sarcasm font. (I prefer the <SARCASM> pseudotag for the benefit of the visually impaired and those reading on devices that don’t have wide font selections and those whose native or primary languages don’t play with fonts the same way that we do… oops, that’s an agenda.)

One might also remember that Orwell — a man who had been shot at and nearly killed thanks to some of those political agendas — remarked that “The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude” (“Why I Write”) at the height of New Criticism’s influence, in some part reacting to demands from other contemporary reviewers to stick to the New Criticism’s precepts as preferred in The Times to the wider-ranging bases accepted in Tribune… or even slightly across the street at the Times Literary Supplement. The less said about either The Telegraph or The Spectator of that period, the better; mentioning certain other sources of “criticism” popular in 1930s and 1940s Britain would constitute An Agenda in itself.

Ransom, Warren (of All the King’s Men fame), Richards, and Empson are not exactly great examples of not having a political agenda in how they defined and restricted what was an acceptable “close reading of the text” — nor in what they refused to engage with at all. Then, too, there’s Brooks; reading The Intentional Fallacy next to “Why I Write” is an interesting exercise, and not just in the grad-school not-veiled-at-all meaning of “interesting” when thrown at someone else’s seminar presentation. Or look at the political mess “textualism” and “originalism” have made of interpreting legal works; consider why virtually all American “originalists” are some flavor of conservative, trending heavily toward outright reactionaries (but not universally so).

There isn’t any social or political baggage in speculative fiction (just like there is no cannibalism in the Royal Navy; and by that, I mean there is a certain amount). You can safely ignore the U-Haul trailer it’s dragging along behind it — the one filled with linguistic artifacts, embedded in texts, of its political and social preconceptions. Or perhaps just go read some of Sheldon’s (and Linebarger’s) works and see what those texts mean.

@67:

But was Wyndham saying that in the authorial voice of “this is what is good and necessary”, or was he putting the words into a character’s mouth, and trusting the reader would recognize the hypocrisy of David Strorm’s new friends?

I ponder that whenever I think about The Chrysalids.

All stories require conflict, and all conflict is political.

Not like old SF ever pushed messages like “exploring space is necessary for survival”, “freedom is good”, or “dumb people will outbreed civilization”. *cough*

Simply delicious, Mr. Nicoll. If the SF I read growing up hadn’t been political, I probably wouldn’t have become a fan of the genre. I’ve always been ferociously political, and I’m old enough to remember my parents’ fury at HUAC and Tailgunner Joe, so I was reading SF basically in the era that you’re writing about.

@39: Wow, that’s disappointing. :(

I read an excerpt from Surreal in the early 70s Houghton-Mifflin reader Galaxies, as an 8-year-old in Denver, and I remember loving it and wanting to read more – but I was never able to find the source book, and I gave up sometime in high school. One of my earliest introductions to SF, and it inspired me to want more.

Oh good lord this article was brillant

@62: The crown of creation.

@55 – there’s nothing intellectually superior about not being affected by bigotry in writing. Generally all it indicates that one is not a member of the group being targeted.

@61

I think that Jerry Pournelle would object to the phrase “subtle politics” referencing his work. He described himself as being to the right of Attila the Hun. Once Byte folded, and he started hosting it on his own server, the Chaos Manor column was full ofhis political complaints.

@75

You may have missed the light sarcasm that some of us have brought to the comments here. Understandable, as Mr Nicoll doesn’t use that particular style in the article we are commenting upon.

I may be able to check “codger” or “old coot” in my profile; I remember inkwell holders in school (the building pre-dated the American Civil War, or avoiding PC-ness, the War to Continue Slavery), but we already had ball-points.

Of course, there was a lot of political agenda in pre-modern SF; it’s just that the agenda was frequently Manifest Destiny in Space! or 19[345]0s (America|Britain) is the perfect society. A lot of the nastiness about the “agenda” in current sf is that it’s not their agenda, which frequently seems to be nostalgia for a past that never was, e.g., that portrayed in 1950s sitcoms.

@@@@@ 74 Katie, I don’t think I implied there was “anything intellectually superior about not being affected by bigotry in writing.” My point was that restricting your reading to authors you already agree with is, in my opinion, aesthetically stifling.

I don’t see anything wrong with wanting to read something without a political agenda right now. I’m being bombarded with politics on all sides, and when I escape into books I want to escape into those without it. I’m not expecting books to be devoid of politics. Any world building is incomplete without it. But I don’t need to be hit over the head with political messages, nor do I need to be shamed for not wanting it.

I’m not sure who is saying older books weren’t pushing agendas. Anyone who read sf in the 50s-60s should know better than that. And if you go back further, sf was often used by literary authors to make political statements about the times, much the way Star Trek does about its times. Frankenstein, anyone?

By no means read Kipling’s Puck of Pook’s Hill,

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/557/557-h/557-h.htm

Nor Rewards and Fairies.

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/556/556-h/556-h.htm#link2H_4_0036

They are full of politics.

The politics of the Norman Conquest.

The politics of the Roman Legions.

The politics of the Spanish Armada.

It’s enough to shiver your timbers.